June 29, 1897: The Chicago Colts’ record romp for 36 runs

Nothing in the buildup suggested it would be remembered more than 100 years later. The Colonels arrived at West Side Park that afternoon for the second of a scheduled three-game series in 10th place in the 12-team National League. The Colts stood 11th. Chicago had lost eight of its last 10 games, while the Colonels had lost 14 of 18.

As might be surmised, Chicago fans didn’t expect much; only 1,150 of them paid to see the game. Even after it was over, The Sporting News managed to dismiss the afternoon’s events in a single-sentence writeup lost amid a sea of page 2 box scores. This was the writeup from start to finish: “The greatest picnic of the season in the line of base ball occurred at the West Side Park today when the Colts broke the record by scoring 36 runs on 32 hits for a total of 51 bases.”1

As might be surmised, Chicago fans didn’t expect much; only 1,150 of them paid to see the game. Even after it was over, The Sporting News managed to dismiss the afternoon’s events in a single-sentence writeup lost amid a sea of page 2 box scores. This was the writeup from start to finish: “The greatest picnic of the season in the line of base ball occurred at the West Side Park today when the Colts broke the record by scoring 36 runs on 32 hits for a total of 51 bases.”1

The laconic nature of that summation says more about sports journalism in the 1890s than it does about the game, which more than a century later remains the most prolific one-team offensive explosion in the history of major-league baseball.

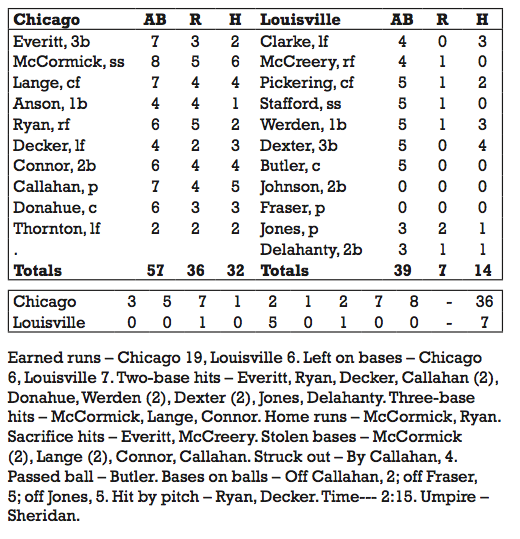

Chick Fraser, a 23-year-old right-hander in his second big-league season, made the start for the Colonels. Fraser would win 175 games—15 of them that season—in a big-league career that lasted into 1909. The club’s 1897 Opening Day starter, Fraser was arguably Louisville’s most reliable arm, although with the Colonels that wasn’t saying much. This was decidedly not Fraser’s day. He allowed three runs in the first inning, five in the second, and six more just one out into the third before being removed in favor of Sheriff Jim Jones, a 20-year-old prospect making his big-league debut.

That was all right with the Colts, who added a seventh run before Jones retired the side in the third, and proceeded to score in every subsequent inning. Barry McCormick, a lightly recalled infielder playing shortstop that afternoon, batted eight times and produced six hits, among them a triple and a home run. Just to rub salt in the numerous Louisville wounds, McCormick also stole two bases. The Colts stole six bases in all. Why? Because, obviously, they could. Right fielder Jimmy Ryan also homered.

The chief beneficiary of this explosion was Colts pitcher Nixey Callahan, who led by 15 runs after 2 1/2 innings—the Colts having exercised their option as the home team of batting first. “Callahan made but little effort to pitch after the third,” the next morning’s papers reported.2 Callahan’s pitching labors may have been half-hearted, but he certainly worked at the plate. He contributed five hits, two of them doubles.

About the only Colt frustrated by what passed for the Colonels’ pitching that day was the best known one, first baseman and manager Cap Anson. The Chicago legend, 45 years old and in the last of his 22 big-league seasons, managed only one hit, although he did walk three times.

Fraser and Jones may have been ineffective, but they didn’t get much help, either. Louisville fielders committed nine errors that afternoon, permitting a staggering 16 unearned runs to cross the plate. Center fielder Ollie Pickering made three of them. That was a sorry fielding performance even by the relatively low standards of 1897.

Perhaps the most amazing offensive statistic of the entire afternoon was this: Chicago led 21-7 at the completion of seven innings, then produced 15 more runs in the eighth and ninth innings alone. Because they had chosen to bat first, the White Stockings hit in the ninth inning despite already leading by 22 runs. The gratuitous insult that followed produced eight additional runs, Chicago’s biggest inning of the afternoon.

Perhaps the most amazing offensive statistic of the entire afternoon was this: Chicago led 21-7 at the completion of seven innings, then produced 15 more runs in the eighth and ninth innings alone. Because they had chosen to bat first, the White Stockings hit in the ninth inning despite already leading by 22 runs. The gratuitous insult that followed produced eight additional runs, Chicago’s biggest inning of the afternoon.

It would improve the story to report that the offensive explosion got the Colts rolling, but that is only partly true. Recovering from his record defeat, Fraser returned to the mound the next day and defeated Chicago 8–7. And although Anson’s Colts did win seven of their next nine games, that brief run lifted them only into 10th place. They finished ninth. The Colonels stumbled home 11th in the 12-team National League.

But nobody had it worse than Jones, the young Louisville reliever who absorbed most of the Chicago onslaught. After playing one more game, he was released and kicked around in the minors before being signed by the desperate Giants at the tail end of New York’s forgettable 1901 season. They threw him out on the mound against the St. Louis Cardinals, and Jones lasted five innings, surrendering six more runs. He never pitched again in the majors, having allowed 28 runs in fewer than a dozen career innings.

This essay was originally published in “Inventing Baseball: The 100 Greatest Games of the 19th Century” (2013), edited by Bill Felber. Download the SABR e-book by clicking here.

Notes

Additional Stats

Chicago Colts 36

Louisville Colonels 7

West Side Grounds

Chicago, IL

Corrections? Additions?

If you can help us improve this game story, contact us.