October 14, 1862: The Martyrdom of Jim Creighton

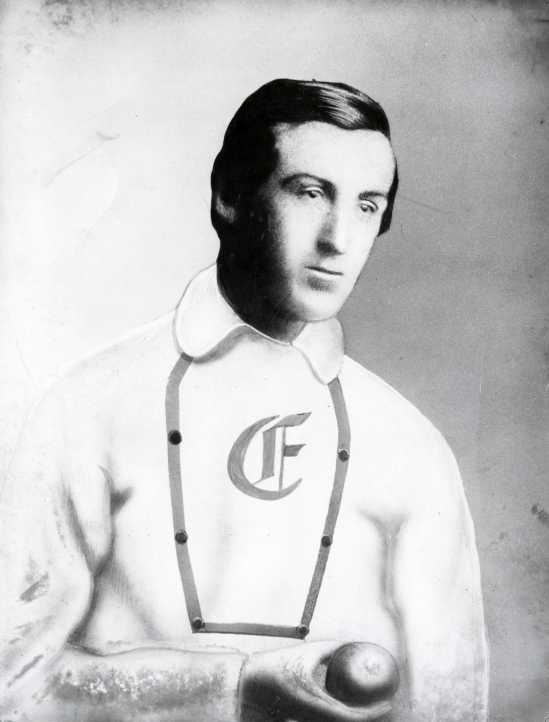

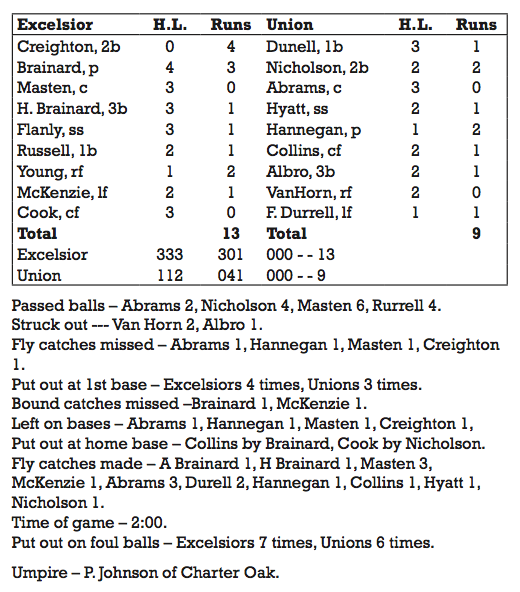

He has been called baseball’s first superstar, its first professional, and a pitching innovator. James Creighton is also central to one of baseball’s earliest legends. It stems from the game in Brooklyn on Tuesday, October 14, 1862, when his Excelsiors hosted the Unions of Morrisania and won, 13-9.

The contest itself wasn’t noteworthy, as reflected in the Brooklyn Eagle’s confession that its report was “very brief,” squeezed by other news.[fn]“Base Ball,” Brooklyn Eagle, October 15, 1862, 2.[/fn] The legend is that during the game Creighton swung so mightily while hitting a home run that the swing caused a serious abdominal rupture. However accurate that is, he suffered for a few days at home after that game and died on the 18th. He was only 21.

The contest itself wasn’t noteworthy, as reflected in the Brooklyn Eagle’s confession that its report was “very brief,” squeezed by other news.[fn]“Base Ball,” Brooklyn Eagle, October 15, 1862, 2.[/fn] The legend is that during the game Creighton swung so mightily while hitting a home run that the swing caused a serious abdominal rupture. However accurate that is, he suffered for a few days at home after that game and died on the 18th. He was only 21.

The Eagle wrote about Creighton’s death at length, and the New York Times, which said he was “extensively known as an expert base ball player,” echoed the Eagle’s statement that Creighton died as “the result of internal injuries sustained while playing a match on Tuesday last.”[fn]“Brooklyn News,” New York Times, October 20, 1862 (see subheading “Death of a Base Ball Player”).[/fn] Creighton’s death was also announced in such papers as the Boston Daily Advertiser, the Public Ledger in Philadelphia, the Sun in Baltimore, Virginia’s Alexandria Gazette, and the Milwaukee Daily Sentinel. The Advertiser’s account called Creighton a “well known base-ball player” and specified that he “burst a blood-vessel in striking at a ball,” though without specifying the result.[fn]Boston Daily Advertiser, October 22, 1862, 2.[/fn]

Creighton was buried at Brooklyn’s Green-Wood Cemetery. A few years later, the Eagle wrote that visitors to his grave would “see a very neat and pretty marble shaft, bearing all the emblems of the Base Ball field, and the name James Creighton. It was erected in conjunction by the Excelsior and Union Clubs.” The paper also provided this account of Creighton’s fateful at-bat: “Hannegan was pitching for the Union, and Creighton was at bat. Hannegan was joking with Jim, and told him he would strike out. Creighton had struck twice, and in making a third attempt at a ball struck with such great force and immediately fell down. After a while he felt no more uneasiness, and played the balance of the game.”[fn]“Our National Game,” Brooklyn Daily Eagle, September 16, 1865, 2. The Eagle’s first use of “struck” was merely to mean “swung,” implying that Bernie Hannegan had in fact attained a strikeout. [/fn]

James P. Creighton, Jr. was born in Manhattan to James and Jane Creighton on April 15, 1841. His mother died when he was 8 years old. A decade later Creighton was playing for the Niagaras of Brooklyn when he had his first chance to pitch. Soon thereafter he switched to the opposing team, the Star Club, and in 1860 he joined the Excelsiors. He impressed during the team’s ground-breaking tour that season, which included a leg through Philadelphia and Baltimore to Washington.

One account of Creighton’s final game appeared in Sporting Life on April 13, 1887, when it reprinted a letter from an unnamed “Old Timer” to St. Louis’s Republican: “Creighton’s death occurred from the rupture of his bladder, which occurred while he was pitching for the Excelsiors against the Unions of Morrisania. I was a kid at the time, and was a spectator of the match. Creighton played out the game, although I think he changed positions and went out into the field to play during the last two or three innings. Some of my companions averred that they heard his bladder burst, but if they did they did not say anything about it at the time, and it was not generally known until the next day that the celebrated pitcher was injured.”[fn]“Creighton’s Death,” Sporting Life, April 13, 1887, 7.[/fn]

Henry Chadwick wrote a rebuttal in his regular column the next issue: “I saw Creighton play in a cricket match at Bedford, on the outskirts of Brooklyn, as a member of the St. George Club, in a game with the Willow Club eleven in 1862, and in that match, in making a very hard effort to hit a leg ball, Creighton unknowingly ruptured himself. Not being aware of the serious injury he sustained on the occasion, he very unprudently engaged in a base ball match with the Excelsiors, of Brooklyn, against the Unions, of Morrisania, and he had not pitched long in the game before he had to retire from his position from pain. On that occasion Creighton said that he had strained himself playing cricket. He went home early that day from the ball match, and the next thing I heard of him was that he had died from the neglected injury he had received in the cricket match; in other words, from a severe rupture.”[fn]“Chadwick’s Chat,” Sporting Life, April 20, 1887, 5. Creighton did star in a cricket match for New York’s St. George Club against Brooklyn’s Willow Club on October 9, 1862, just five days prior to the Excelsiors’ game against the Morrisania nine.[/fn]

In recent years some baseball historians have speculated that shortly after Creighton’s death influential baseball figures, led by the Excelsior club’s president, Dr. Joseph B. Jones, attempted to shift blame to cricket, its rival then for “national pastime,” so that baseball wouldn’t be viewed as dangerous. If there was such a plot, it didn’t blossom. By 1887, when Chadwick weighed in, there was no need for excuses.

A contrary accusation is that Creighton’s death from hitting a home run was quickly fabricated to enhance baseball’s popularity. “Dying while hitting a long home run is a great story, it’s just not true,” said Tom Shieber, senior curator of the National Baseball Hall of Fame, a few years ago.[fn]Wayne Coffey, “Daily News Sports Hall of Fame Candidates,” New York Daily News, June 18, 2006.[/fn] Shieber’s search of original sources found no homer by Creighton in that fateful game. Still, the home-run myth was probably popularized, if not started, almost half a century later by Creighton’s teammate, John Chapman. In Alfred Spink’s 1910 book The National Game, Chapman was quoted as saying, “I was present at the game between the Excelsiors and the Unions of Morrisiana [sic] at which Jim Creighton injured himself. He did it in hitting out a home run. When he had crossed the rubber he turned to George Flanley and said, ‘I must have snapped my belt,’ and George said, ‘I guess not.’”[fn]Alfred H. Spink, The National Game (St. Louis: The National Game Publishing Co., 1910), 128. [/fn] Despite many authors questioning this legend, it still shows up in print to this day presented uncritically.

Overlooked in this saga is the remainder of James Creighton’s father’s very sad life. In little more than a decade after 1862, Jim Creighton, Sr. also buried a daughter, Mary, a grandchild, and another son, John. They are all buried near James Senior’s wife and namesake.

This essay was originally published in “Inventing Baseball: The 100 Greatest Games of the 19th Century” (2013), edited by Bill Felber. Download the SABR e-book by clicking here.

Additional Stats

Excelsiors of Brooklyn 13

Unions of Morrisania 9

Excelsior Grounds

Brooklyn, NY

Corrections? Additions?

If you can help us improve this game story, contact us.