Danny Goodman

Hustling isn’t just for ballplayers. It’s for novelty salesmen, too. Danny Goodman wasn’t just a guy to crank out caps and keychains, but one who was always looking for a fresh opportunity to transfer money from the customer’s pocket to the Los Angeles Dodgers’ cash registers. For 25 years he presided over an operation that he said made the Dodgers Major League Baseball’s leader in souvenir sales.

Hustling isn’t just for ballplayers. It’s for novelty salesmen, too. Danny Goodman wasn’t just a guy to crank out caps and keychains, but one who was always looking for a fresh opportunity to transfer money from the customer’s pocket to the Los Angeles Dodgers’ cash registers. For 25 years he presided over an operation that he said made the Dodgers Major League Baseball’s leader in souvenir sales.

In 1958 the Dodgers’ first year in the Coliseum, individual fans rose in the stands to play a six-note bugle call that had elicited the cry of “Charge!” at University of Southern California football games for years. The crowd was happy to respond. Goodman went out and found a manufacturer to make foot-long brass trumpets. They sold for $1 and came with instructions for playing those six notes.1

Goodman was born into a Russian-Jewish immigrant family in Milwaukee on May 17, 1912. His father, Frank, who’d worked as a baker’s apprentice, a machinist, and a broom salesman, had been born in the United States, but his mother, Anna, had been born in what is now Belarus, immigrated in 1904, and married Frank a few years later. Frank’s parents had immigrated from what is now the Ukraine in the early 1880s. Although he would be called Danny all his adult life, Goodman was named Albert at birth. There was an older sister, Rose, and a younger brother, Joseph.2

Danny said his father had died when he was 11, but the 1930 census listed Anna as divorced rather than widowed.3 Either way, Danny began hustling to help the family. He said he went looking for a job at Borchert Field, home of the American Association’s Milwaukee Brewers, but Jacobs Brothers, the stadium’s concessionaire, told him he was too small. So Danny showed up early every weekend day, sacked all the peanuts, and lugged the wooden crates of soda around the park.4 Eventually he got a job selling candy and “felt like a rich man” after earning $1.25 his first day.5

By the 1930 census, Goodman was done with school and working as a newspaper distributor. The lack of education and the work ethic of someone who needed to feed the family would characterize the remainder of his life.

Goodman was quick on his feet because he’d spent almost four decades in the entertainment business before he joined the Dodgers. He’d worked in burlesque houses and ballparks since the 1920s, becoming famous for his attacks on the English language. Goodman was “an off-the-field syntactical equivalent of Yogi Berra,” said Los Angeles Times columnist Jim Murray. “I may not be the best talker, or the best educated man in this room, but at least I’m illiterate,” Goodman responded.6

Over time, Goodman came to accept the entertainment industry’s belief that all publicity was good and the impact of the stories he told reporters was far more important than the accuracy of the details.

At different times he told different reporters that he’d dropped out of school and started working when he was 11, or 12, or 14, or 17.7 He expanded from paperboy to vendor for the Jacobs Brothers, who served burlesque houses and theaters as well as Borchert Field. Within a few years, he was a full-time employee.

In Goodman’s teens, the Jacobs Brothers were already sending him to handle their various operations around the country. In the late 1920s, he said, he was in Baltimore running the Jacobs’ concession operation for Jack Dunn’s International League Orioles. There is some doubt about this claim because the 1930 census, taken in April, found him living at home with his mother and siblings.8 By the early 1930s, he said, he’d been moved to Newark of the same league, where he worked for George Weiss. But he moved around handling any assignment – race track, theater, or stadium – that the Jacobs Brothers needed. He did dozens of minor-league parks, race tracks, theatres, and circuses.

In 1934 Jacobs Brothers moved all their top operators to Detroit for the World Series. Goodman was given charge of the outfield bleachers and was doing a tremendous business in pies. The business picked up even more in the seventh game. After St. Louis outfielder Joe Medwick slid hard into Detroit third baseman Marv Owen in the sixth inning, the Tiger fans, already upset that the home team was losing badly, showered Medwick with food and trash when he took the field. Eventually, baseball commissioner Kenesaw Mountain Landis would make his well-known decision ordering Medwick out of the game. He also made a less well-known decision, ordering Goodman to stop selling pies.9

Goodman learned all the tricks. In those days, vendors turned in their unsold merchandise at the end of the game and were refunded what they’d paid the concessionaire. As part of his education, Goodman found that cola salesmen filled empty bottles with coffee and turned them back. Ice-cream vendors put wood blocks in empty cartons. One hot-dog vendor painted his forefinger with iodine, slipped it into the bun, let the customer see it and then pulled the reddened finger back. When the customer complained that there was no frankfurter, the vendor suggested that the customer had dropped it.10

One day Goodman caught the unmistakable fragrance of kosher hot dogs, which Jacobs Brothers didn’t sell. He found a vendor who was bringing his own supplies to the park.11 At the Coliseum and Dodger Stadium, he didn’t have to worry about the food vendors, as his job covered just the souvenir stands and sales of advertising in the yearbook and game programs. He also handled concessions at Wrigley Field, the Pacific Coast League ballpark the Dodgers owned for their first couple of years in Los Angeles. It was rented out for rodeos, soccer games, and other events. He soon added the expansion Los Angeles Angels to his client list, filling the same roles as he did with the Dodgers.

As the 1962 season wound down, both the Dodgers and the Angels remained in the thick of their pennant races. The Dodgers weren’t eliminated until a playoff series with the Giants, and the Angels didn’t fade until September. By then Goodman had sold the advertising for both World Series programs and, for the Dodgers, worked up a whole series of World Series souvenirs.12 He ordered 10,000 seat cushions and 20,000 drinking glasses labeled “Dodgers vs. Yankees 1962.”13 He estimated that cost the Dodgers $50,000, but that was life.14

As his experience grew, Goodman started making up tricks of his own. In Reading, Pennsylvania, he found that customers wouldn’t pay a nickel to rent seat cushions. So he had the seats hosed down.15 He claimed to be the first to sell hats and pennants.16 Chuck Stevens, who played for the Pacific Coast League Hollywood Stars, said Goodman came up with the idea of dragging the infield between innings during the years Jack Salveson pitched for the Stars. Salveson, a fast worker with excellent control, tended to pitch short games and Goodman needed the extra time to sell food and souvenirs.17 At many parks the practice was to let boys into the park early to pack the peanut bags, paying them by letting them eat as many peanuts as they wanted. Goodman found that by giving the boys free chewing gum just as they went to work, they’d eat many fewer peanuts.18

Jacobs Brothers had moved Danny Goodman to Hollywood for the 1939 baseball season and the opening of Gilmore Field. It was a match made in heaven. A number of real Hollywood stars (Gary Cooper, George Raft, Robert Taylor, Cecil B. DeMille, Barbara Stanwyck, Bing Crosby, and William Powell among others) owned stock in the team.19 Bob Cobb, owner of the Brown Derby restaurants, was the principal owner and persuaded Goodman to expand the Gilmore menu to a higher class of food. Soon, Goodman said, they were back to hot dogs and hamburgers because that’s what Raft and the others wanted when they showed up.20 “We’ve experimented with dozens of chef’s specials, but they’ve all been a flop in the pan,” Goodman explained.21

Gilmore Field became known as a place where starlets could get their pictures taken and Danny Goodman was only too happy to pose them holding the newest of his souvenirs. He could also get entertainment-industry friends to pitch in. When he introduced the toy trumpets to the Coliseum, he brought jazz trumpet great Ziggy Elman to ham it up with the merchandise.22

When the Dodgers moved West, Goodman’s position became uncertain. He’d been with Jacobs Brothers (by then known as Sportservice Inc.) for nearly three decades. He’d already turned down their offers to run major-league concessions elsewhere.23 Aside from a couple of years in the Air Force in World War II, he’d been in Los Angeles for 20 years.24 Goodman also oversaw the PCL’s Los Angeles Angels concessions and Jacobs’ operations elsewhere on the West Coast, which included several race courses in the San Francisco area and most PCL ballparks.25 But Jacobs Brothers had no anchor to keep him in Los Angeles and he had come to enjoy the Hollywood life thoroughly.

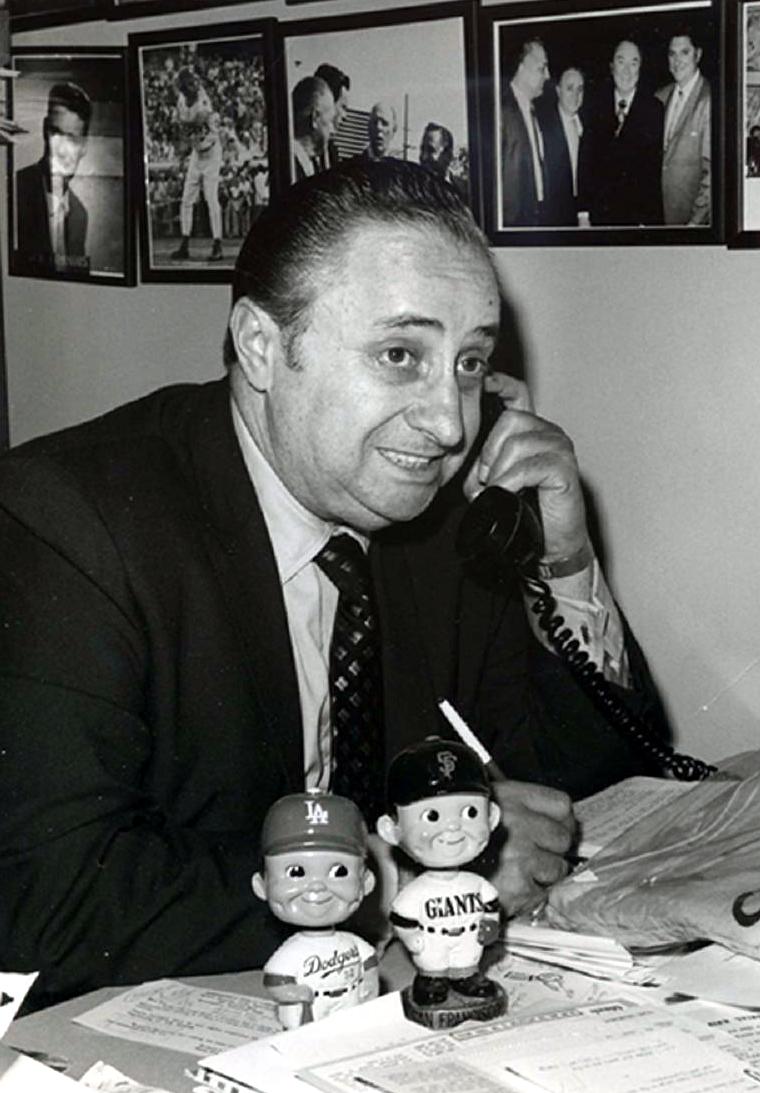

Danny Goodman lived in Beverly Hills 90210 before it became famous. He was an early riser who was usually in the office before 6. He spent the morning on the phone, doing meetings and setting up business. He’d have a long lunch at a very public restaurant or club, always ready to talk, tell stories, and buy drinks for reporters. He’d take a midafternoon nap, go to the ballpark or another public dinner, and be in bed by 10 or so.26

Goodman was a guy always willing to buy a drink, give a gift, or do a favor, especially for a reporter or somebody from the movies or television. Through the 1950s, he was the only non-entertainment-industry figure who’d been the subject of a Friars’ Club roast, an honor he received in 1953.27 Ronald Reagan acted as “roastmaster,” with Jack Benny, Phil Silvers, George Burns, Chico Marx, and others pitching in. Goodman was also honored with similar dinners by the Leukemia Foundation of California and the Westwood Shrine Club.28 He did a lot of volunteer work, serving on the Friars’ board of directors for 32 years, and organizing benefit dinners for other clubs.29 He also helped organize dinners for Ty Cobb, Stan Musial, Casey Stengel, Maury Wills, Vin Scully, Lefty O’Doul, Leo Durocher, Sandy Koufax, and a host of Hollywood types and other celebrities. “You want celebrities for this event?” he asked one group, “I’ll get you celebrities you never even heard of.”30

The Dodgers arrived with a front-office crew from Brooklyn and the Coliseum’s concessions contract locked up by rival ABC Vending Co., which had handled the Coliseum for years.31 Bob Hunter, who covered the Dodgers for the Los Angeles Examiner, later told how he kept urging Dodgers owner Walter O’Malley to meet Goodman. Eventually Hunter picked up the phone in O’Malley’s Statler Hotel office and made the call himself, shoving the phone into O’Malley’s hand. It was a shove O’Malley would never regret. Goodman served as vice president, advertising for 25 years. Hunter said later O’Malley told him, “That was a great thing you did that day.”32

Goodman was always looking for new ideas. He said he first saw bobblehead dolls when a Japanese manufacturer brought them to him in 1958.33 They became a staple, with the Dodgers one of the first teams to adopt them. He came out with plastic bats in 1958 as well, and his supplier had to go to double shifts by the item’s second month.34 When the Dodgers opened in the Coliseum, Goodman offered a dozen brands of hats, from Tyroleans with a feather to sun visors. The roofless Coliseum, baking in the Southern California sun, proved an excellent place to sell woven straw coolie hats ($1.50) and Goodman gave them a larger and larger role. Even O’Malley bought one, but refused to have his picture taken wearing it.35

With two months left in the 1958 season, Goodman’s novelty operations had contributed more than $200,000 to the team’s profits.36 By the end of the season, Goodman reported, Dodger fans had bought more souvenirs than all other major-league teams combined.37 And that was just at the ballpark. He had also persuaded Sears and local department store chains to carry the Dodger merchandise.38 With a year’s experience, Goodman rolled out an even more lavish array for the Coliseum’s 15 novelty booths in 1959. There were 12 hat styles and 33 other items from bolo ties to pillowcases to complete child-sized uniforms.39 There were aprons emblazoned: “To Heck with Housework, let’s go to the ball game.”40

But selling souvenirs was not always a sure thing. Even the bugles didn’t work out. They shattered when dropped by kids, and adults had a distressing tendency to expect them to work well. O’Malley made him discontinue the line.41

Goodman continued in the job for 25 years because he kept his eye on the big picture as well as managing the details. In 1962 he made a prediction that had not come true when he died on June 16, 1983, but has since then: “I think eventually we’ll have full-scale shopping centers inside the parks. After all, we’re dealing with a captive audience for three or four hours. Eventually, we’ll be taking full advantage of it.”42

Notes

1 “Quotes” column, The Sporting News, March 25, 1959, 12.

2 US Federal Census for 1900, 1910, 1920, 1930, and 1940, and Wisconsin state census for 1905.

3 Bob Oates, “Danny Is a Dandy Man in Big Sell,” The Sporting News, May 10, 1961, 13.

4 Ned Cronin column, Los Angeles Daily News, September 4, 1947.

5 Frank Finch, “Dodgers Find Champ Salesman in Goodman,” The Sporting News, May 14, 1958, p. 13.

6 Charles Maher, “The Munificent Mr. Malaprop,” Los Angeles Times, August 29, 1971.

7 Bob Hunter in The Sporting News, October 27, 1962, 9; Ned Cronin in the Los Angeles Daily News, September 4, 1947, 34; Vincent Flaherty column from Los Angeles Examiner in The Sporting News files, marked February 1956; Frank Finch in The Sporting News, May 14, 1958, 13. Goodman also reported that he went to work for the Stars in 1937, 1938, and 1939 in different interviews, but since all the interviews tied his start to the opening of Gilmore Field, it seems safe to place it in 1939, the year the park did open. These articles provide much of the detail for Goodman’s claims about his early career.

8 1930 US Federal Census.

9 Bob Hunter, “Good-Guy Goodman—Dodger Super Salesman,” The Sporting News, October 27, 1962, 9.

10 Ned Cronin column, Los Angeles Daily News, April 4, 1951.

11 Frank Finch, “Dodgers Find Champ Salesman in Goodman,” The Sporting News, May 14, 1958, 13.

12 Bob Hunter, “Good-Guy Goodman—Dodger Super Salesman,” The Sporting News, October 27, 1962, 9.

13 Melvin Durslag column, Los Angeles Herald-Examiner, September 27, 1963.

14 Charles Maher, “The Munificent Mr. Malaprop,” Los Angeles Times, August 29, 1971.

15 Ned Cronin column, Los Angeles Daily News, September 4, 1947; Bob Hunter, “Good-Guy Goodman—Dodger Super Salesman,” The Sporting News, October 27, 1962, 9.

16 Talk! Talk! Column, Los Angeles Major League Baseball News, April 15, 1963 (saying he started in 1940 in Hollywood), and Charles Maher, “The Munificent Mr. Malaprop,” Los Angeles Times, August 29, 1971 (in which he said it was 1931 in Newark).

17 Interview, Chuck Stevens, May 17, 1997; Talk! Talk! Column, Los Angeles Major League Baseball News, April 15, 1963; “The Munificent Mr. Malaprop,” Los Angeles Times, August 29, 1971. This claim is open to question. Jon Light’s Cultural Encyclopedia of Baseball (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland, 1997), 308, says the custom of dragging the infield was invented by the Cincinnati Reds between 1949 and 1951. Cincinnati general manager Gabe Paul is quoted as saying the custom led to greater concession sales. Interestingly, Salveson pitched for the Stars from 1949 to 1951, the same time period. Stevens played for the Stars from 1948 to 1954.

18 Los Angeles Times, July 11, 1957.

19 Richard Beverage, Hollywood Stars: Baseball in Movieland, 1926-1957 (Placentia, California: Deacon Press, 1984), 99.

20 Ned Cronin, “Cronin’s Corner,” Los Angeles Times, July 11, 1957.

21 Charles Maher, “The Munificent Mr. Malaprop,” Los Angeles Times, August 29, 1971.

22 Al Wolf, “Souvenir Salesman’s Dream – a World Series in Coliseum,” The Sporting News, August 26, 1959, 15.

23 Ned Cronin column, Los Angeles Daily News, September 4, 1947.

24 Ned Cronin column, Los Angeles Daily News, September 4, 1947.

25 Clipping from The Sporting News’ Danny Goodman file; Vincent Flaherty column in the Los Angeles Examiner dated February 1956. Also Los Angeles Times, October 24, 1957.

26 Charles Maher, “The Munificent Mr. Malaprop,” Los Angeles Times, August 29, 1971.

27 Frank Finch, “Dodgers Find Champ Salesman in Goodman,” The Sporting News, May 14, 1958, 13.

28 Frank Finch, “Dodgers Find Champ Salesman in Goodman.”

29 Frank Finch, “Dodgers Find Champ Salesman in Goodman”; “Danny Goodman Dies; Dodgers’ Concessionaire,” Los Angeles Times, June 17, 1983.

30 Charles Maher, “The Munificent Mr. Malaprop,” Los Angeles Times, August 29, 1971.

31 Los Angeles Times, February 6, 1958.

32 Bob Hunter, “Good-Guy Goodman—Dodger Super Salesman,” The Sporting News, October 27, 1962, 9.

33 Charles Maher, “The Munificent Mr. Malaprop,” Los Angeles Times, August 29, 1971. The article claims that the Dodgers were the first to sell bobbing head dolls in the US, but 14 teams, including three in the Pacific Coast League, were selling them a year before the Dodgers. See Tim Hunter. Bobbing Head Dolls, 1960-2000 (Iola, Wisconsin: Krause Publications, 1999), 12.

34 Los Angeles Times, May 30, 1958.

35 After the first nine home games, Goodman said he’d sold 5,000 coolie hats. Los Angeles Times, April 29, 1958.

36 Rube Samuelson, “Dodgers Taking Healthy Lead in Hot Dog League,” The Sporting News, August 6, 1958.

37 Sid Ziff, ‘Adult Buyers Boomed Dodger Novelty Sales,” The Sporting News, January 14, 1959, 13.

38 Jeane Hoffman, “How to Top ‘Charge’ Bugles –That’s Job of Danny Goodman,” Los Angeles Times, April 7, 1960.

39 Los Angeles Times, March 10, 1959; Jeane Hoffman, “20,000 Bugles Ordered for Sale to Dodger Fans,” The Sporting News, March 25, 1959, 12.

40 Los Angeles Times, August 26, 1963.

41 Jim Murray, “Baseball Novelty,” Los Angeles Times, May 11, 1971.

42 Sid Ziff, “Sideline Business,” Los Angeles Times, August 12, 1962.

Full Name

Born

May 17, 1912 at Milwaukee, WI (US)

Died

June 16, 1983 at Beverly Hills, CA (US)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.