Huntington Avenue Grounds (Boston)

This article was written by Ron Selter

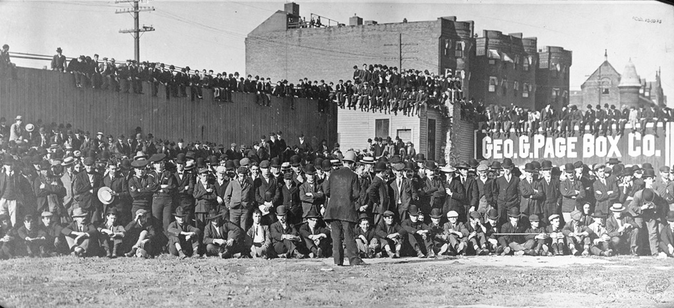

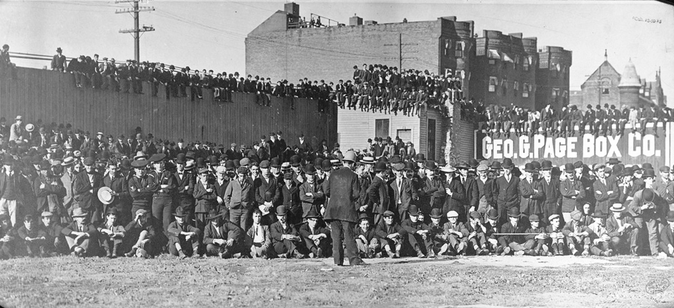

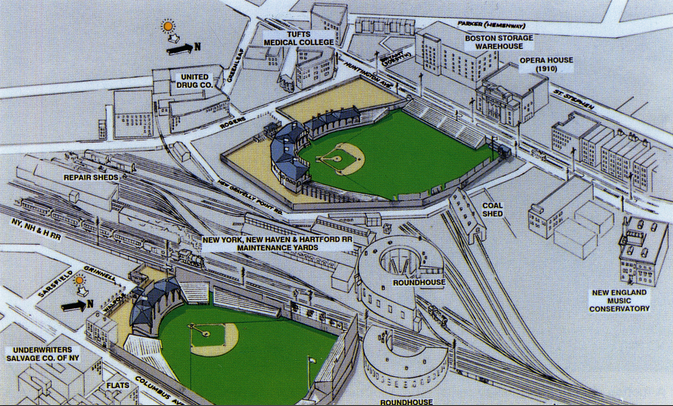

Before the 1901 season the ballpark called Huntington Avenue Baseball Grounds was built for the AL Boston franchise (the team, later called the Red Sox, was known for the first seven seasons as the Boston Americans). The ballpark site was located at Huntington and Rogers Avenues, in the Roxbury section of Boston, and was just North, across the railroad tracks and yards, from the National League’s Boston park, the South End Grounds. The Huntington Avenue site had previously been used as a temporary location for carnivals and traveling circuses, and as a result the area was dubbed the Huntington Carnival Lot.1 The site was leased by Charles Somers, who in addition to being the owner of the Cleveland franchise in 1901, was the financial backer of the Boston American League entry.2

The story of the selection of the site and the acquisition of the lease is told in Bill Nowlin’s recent book Red Sox Threads:

Connie Mack, owner of the Athletics, was involved with the Boston Americans, too; he headed the small group selected to find a suitable site for the AL’s Boston franchise. They visited possible locations in Cambridge, Charlestown, and Boston, but finally settled on a site not far from the National League park, the South End Grounds. The site was owned by Durand Associates and leased to the Boston Elevated Railway Company. Mack’s committee (which comprised Hugh Duffy and Tommy McCarthy) asked John Dooley to speak with his partner in the J. R. Prendergast Company, a cotton brokerage. Daniel Prendergast was also a director of Boston Elevated Railway, and Dooley recalls an old newspaperman named Peter Kelley coming to his office on behalf of team owner Charles Somers to ask that Prendergast help convince the railway company to accept the site. Dooley says he prevailed upon Prendergast to have the Elevated accept the offer of $5,000 for the rights to use the land. It was Connie Mack who signed the lease on the Huntington Avenue land.

To say the site was unimproved was an understatement. It was, in the words of Ed Walton, “no more than an expansive wasteland made up of heavily weeded bumps and lumps.” It had been used as a circus lot – even the temporary home to Buffalo Bill’s traveling Wild West Circus when a show would come to town. There was a fairly large pond on the property that children would splash into during summer months from a number of chutes they would slide down, as a water slide. In the winter, of course, people could ice skate there, but this was no high society skating pond. The area was largely bounded by rail yards, a huge Boston Storage Warehouse behind the length of the left-field bleachers, some stables, breweries, and a pickle factory. The United Drug Company was situated near enough to the park that one could often smell the chemicals at work.3

Plans for the park were completed in February 1901, and called for a covered grandstand and uncovered bleachers located down the first and third base lines. Total seating capacity was to be 9,000 patrons.4 Groundbreaking for the park was March 7, 1901. The structure of the grandstand was built with expanded metal and roughcast concrete.5 The rest of the park was built of wood, and the roof rested on 28 foot columns. There were four entrances to the park – two on Huntington Avenue and two on Rogers Avenue. One of the two entrances on Huntington Avenue, the one near the left-field corner, was the access point for a wide walkway into the park which was at an angle to both the left-field foul line and the Huntington Avenue fence. This diagonal walkway thus limited the left-field distance and made the left-field dimension necessarily less than the distance from home plate to the Huntington Avenue fence. There was a sloping embankment in left field in front of the Huntington Avenue fence that started about 50 feet in front of the fence and was used to accommodate standee overflow crowds. At the time of the 1901 opening of the park, there were no stands or bleachers in the outfield. The grandstand and home plate were in the southwest corner of the park site. An odd feature of the park was a large in-play tool shed located in center field. In addition there was an in-play scoreboard mounted above the fence in right-center field.

After the 1904 season, a rectangular set of bleachers was added in left field.6 These bleachers ran from a short distance left of the center-field corner to nearly the junction of the entrance walkway fence and the Huntington Avenue fence. These bleachers did not, because they could not, run all the way to the left-field foul line. These bleachers consisted of 14 rows of seats, and had a low fence in front, and this last feature contributed to a number of bounce home runs into the left-field bleachers starting with the 1905 season. The addition of these left-field bleachers increased seating capacity by an estimated 3,500 seats. According to the Boston Globe-the park’s total capacity, reported as 9,000 when the park opened in 1901, was now surprisingly reported to be about 17,000. The next change to the ballpark was before the 1909 season. A 1909 game account by the writer for the Chicago Tribune included the observation, “President Taylor (of the Boston Red Sox) improved the park – new bleachers in CF, and moved the press box to the roof”.7 There was no mention of any increase in seating capacity. The next expansion was before the 1910 season and involved the extension of the third-base bleachers into fair territory in left field. This new section of seating crossed the left-field foul line at about a 45-degree angle and extended to within 20-25 feet of the pre-existing left-field bleachers. Having two set of bleachers referred to as left-field bleachers starting with the 1910 season, led in the newspaper game accounts to numerous ambiguous references to home runs hit into the “left-field bleachers”.

The Red Sox stayed at Huntington Avenue Grounds until the end of the 1911 season, when they moved into one of the first classic ballparks – Fenway Park. The Red Sox took the sod with them from Huntington Avenue Grounds to use in the infield at Fenway Park.

Park Configurations and Dimensions

Unlike the case with many other early Deadball Era ballparks, there is no shortage of dimensional data for Huntington Avenue Baseball Grounds. The problem is that the available dimensional data have the unfortunate characteristic of being in substantial disagreement. The configurations and dimensions shown below are in part estimates and in part are based on park diagrams. Where possible, ballpark photos have been used to confirm or disprove reported dimensions. The listed outfield dimensions for Huntington Avenue Grounds were taken from Green Cathedrals.8 They are:

1901-07

- LF: 350, LCF: 440, CF: 530, RF: 280

1908-11

- LF: 350, LCF: 440, CF: 635, RF: 320

The original plans for the building and the configuration of Huntington Ave Grounds, as reported in the Boston Globe, included a park diagram and outfield dimensions.9 This article and diagram gave the park’s dimensions as LF 350 feet, CF 530 feet, and RF 320 feet. One limitation of this diagram is that the diagram did not extend to the right-field fence. The diagram ends in left-center field at the 32-degree point along the Huntington Avenue fence, and also ends along the right-field foul line about 75 feet before the right-field corner. The alignment of the right-field fence was derived from a 1904 photo in the Boston Globe.10

In this photo, the fence at the back of the angled first-base bleachers extends, at an angle of noticeably more than 90 degrees to the foul line, into fair right field for about 30-40 feet. At this point there is a kink in the fence to the left as one moved away from the right-field corner. A second photo of the park, taken for the 1903 World Series, also shows the right-field fence from the foul line to past the kink.11 The right-field fence beyond the kink, to meet the left-field fence at the center-field junction (at a home plate-center field distance of 530 feet), must have been aligned at 95 degrees to an extension of the right-field foul line. A new diagram on a larger scale was drawn using all of the above data. All subsequent ballpark dimensions, were derived using this diagram.

The 1908 center-field distance of 635 feet, listed in Green Cathedrals, can only have been correct if the park was expanded towards the east and the right-field fence realigned at much more than 95 degrees to the foul line. In addition, as the center-field bleachers were added for the 1909 season, the center-field dimension of 635 feet could have existed for only that one season.

The 1901 right-field dimension of 280 feet listed in Green Cathedrals bears closer examination. In the seven seasons that the Huntington Ave Grounds right-field dimension of 280 feet was said to be in effect (1901-07), there were a grand total of only four home runs hit over the right-field fence. This works out to be a rate of 0.6 over-the-fence home runs to right field per season. By comparison, the right-field distance at Columbia Park (Philadelphia AL) was 280 feet. At Columbia Park in the 1901-08 seasons, home runs over the right-field fence averaged 9.8 per season – some 16 times the rate of comparable home runs at Huntington Avenue Grounds. Thus, in addition to being contradicted by the 1901 listed right-field dimension, the home run data show that it is most unlikely that the right-field dimension at Huntington Avenue Grounds was ever 280 feet.

The left-field bleachers, built before the 1905 season, were located on the Huntington Avenue Grounds diagram based on a photo and story in the Boston Globe.12 From this photo the left-field bleachers were determined to be 14 rows deep with a narrow walkway in front just behind a short fence. The depth of these bleachers was estimated at 27 feet, at ground level. The front of the bleachers if extended to the left-field foul line would have intersected the foul line at a distance of 348 feet from home plate. The horizontal extent of the left-field bleachers was estimated from the photo in the Boston Globe. The left end of the bleachers was about 20 feet to the right of the junction of the walkway fence with the Huntington Avenue fence. The right end of the bleachers extended to nearly dead center field.

The park diagram, with the left-field bleachers added to it, was used to estimate the dimensions for the 1905-08 time period for left field and center field (right field was unchanged during the life of the park). The location of the center-field bleachers added for the 1909 season was based on two factors: (1) game accounts of inside-the-park home runs hit “to the flagpole” during the 1910 season – which establishes that the flagpole was still in play, and (2) photos that showed the location of the flagpole to be in front of the right side of the center-field fence. Therefore the center-field bleachers must have been located behind the flagpole. The location and extent of the left-field bleachers, added for the 1910 season by the extension of the third-base bleachers, was based on a photo in Diamonds.13

The new 1910 left-field distance of 305 was derived from a story in the Boston Post where sportswriter Paul Shannon commented that the LF distance at the then new Fenway Park would be 19 feet more than left field at Huntington Ave Grounds.14 The left-field distance at Fenway Park when it opened in 1912 has been found to have been 324 feet. Adding the third-base bleachers to the park diagram such that they cut the left-field foul line 305 feet from home plate established the location of the front of the bleachers. These bleachers extended about 50 feet past the foul line into fair left field. Park data and dimensions for Huntington Avenue Grounds are shown below:

Dimensions (From Park Diagrams)

| Years | LF | SLF | LC | CF | RC | SRF | RF |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1901-04 | 350 | 388 | 433 | 530 | 412 | 365 | 320 |

| 1905-08 | 350 | 360 | 402 | 530 | 412 | 365 | 320 |

| 1909 | 350 | 360 | 402 | 456 | 412 | 365 | 320 |

| 1910-11 | 305 | 360 | 402 | 456 | 412 | 365 | 320 |

Average Outfield Distances

| Years | LF | CF | RF |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1901-04 | 393 | 470 | 366 |

| 1905-08 | 370 | 457 | 366 |

| 1909 | 370 | 441 | 366 |

| 1910-11 | 363 | 441 | 366 |

Fence Heights (from Green Cathedrals and estimated from photos)

| Years | LF | CF | RF |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1901-04 | 14 | 14 | 14-28* |

| 1905-08 | 6-14 | 6-14 | 14-28* |

| 1909 | 6-14 | 6-14 | 14-28* |

| 1910-11 | 3-14 | 6-14 | 14-28* |

* The 28-foot fence height was only at the scoreboard mounted above the RF fence

- Capacity: 9,000 (1901-04), 12,500 (1905-08 est.), 14,000 (1909-11 est.),

- Park Size – Composite Average Outfield Distance: 410 (1901-04), 398 (1905-08), 392 (1909), 390 (1910-11)

- Park Site Area: 6.3 acres

- Deadball Era Run Factor: 102 (Rank: AL 8)

Impact of the Park’s Configurations and Dimensions on Batting

In the park’s original 1901-04 configuration, Huntington Avenue Grounds, along with Baltimore’s Oriole Park IV, was the largest park in the American League. Unlike today where large parks (adjusted for altitude in the case of Coors Field) are known as pitchers parks, Huntington Avenue Grounds was average or above average in every offense category except doubles (see data in the Batting Park Factors table below).

In 1903 the American League adopted the foul-strike rule – foul balls with less than two strikes on a batter would now be counted as strikes. Despite this rule change which reduced overall batting average in the AL by about 15 points, the home batting average for the 1903 Boston Americans increased from .280 in 1902 to .296 in 1903. The batting average park factor, 98 in 1901, and 97 in 1902, jumped to 108 for 1903. One possible contributing factor is that the negative impact of the adoption of the foul-strike rule affected Huntington Avenue Grounds much less than the other AL ballparks. Another indirect contributing factor was the elimination of Burns Park in Detroit and Oriole Park IV in Baltimore. Unlike in 1902 Burns Park, which was an extreme hitter’s park (with a batting average park factor of 116), was not used in 1903. When the Baltimore franchise was transferred to New York, Oriole Park IV (with a 1902 batting average park factor of 108) was replaced by Hilltop Park in New York (1903 batting average park factor of 97). As these two changes made the other American League parks worse for hitters, the batting average park factor for Boston’s Huntington Avenue Grounds and the other AL parks increased. However, these two factors are believed to be only partial explanations with no explanation having been found for the entirety of the large increase in the Huntington Avenue Grounds batting average park factor.

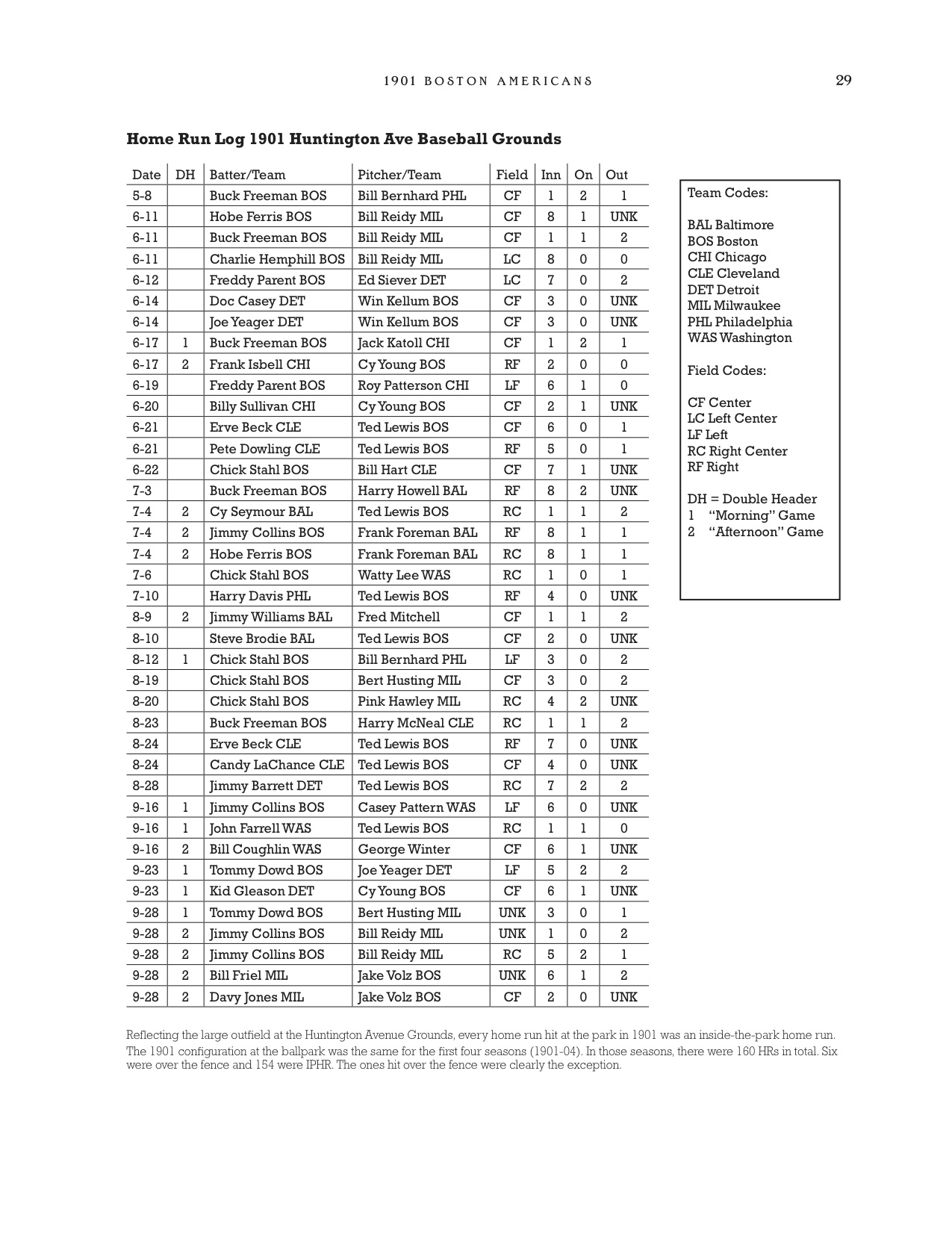

The large outfield dimensions at Huntington Ave Grounds turned hits that would have been doubles at other parks into triples and inside-the-park home runs (IPHR). With the generous outfield dimensions in the park’s original configuration, nearly all (97 %) of the home runs were IPHR, as over-the-fence (OTF) home runs were rare – there only four such home runs. Despite being the biggest park in the AL, Huntington Ave Grounds managed to post the third-highest home run park factor in the 1901-04 time period (only Washington 1901-03 at 189, and New York 1903-04 at 208 had higher home run park factors).

The effect on batting of the installation of the left-field bleachers for the 1905 season was noticeable, but generally not very substantial. The 1905-09 park factors decreased slightly for batting average, on-base, and slugging. The park factor for doubles increased slightly, while triples decreased (156 to 132) as one would expect with the shorter left field and left-center field dimensions. The small decrease in the batting average, on-base percentage, and slugging park factors may have been due to the poorer batters background that resulted from the new outfield bleachers that extended into center field. One noticeable effect of the installation of the new left-field bleachers was more home runs and more OTF home runs (an impressive sounding 425 % increase in OTF home runs – but still amounting to only four per season), most of which (15 of 21) were of the bounce variety. Thus the left-field bleachers led to the number of bounce home runs increasing from less than one per season (1901-04) to about four per season (1905-08). Nearly all of the bounce home runs hit in the 1905-08 seasons were hit into the left-field bleachers.

For the 1909 season, with the construction of CF bleachers, the proportion of IPHR declined to 58% of the total vs. 81% in 1905-08. The extension of the third-base bleachers into left field starting with the 1910 season led to lower 1910-11 park factors for batting average, on-base percentage, and slugging. The park factor for doubles increased, while the triples park factor decreased (132 to 82), as one would expect with the shorter left-field dimension. At the same time total OTF home runs and OTF home runs to LF increased sharply. OTF home runs (excluding bounce home runs) were 2.0 per season in 1905-09 and 18.5 in 1910-11. OTF home runs to left field went in the same time periods from 1.25 per year to 15 per year.

As would be expected with the shorter left-field and center-field dimensions, the proportion of IPHR dropped again, this time to 47% of the 1910-11 total home runs. In addition the successive changes in configurations led to changes in the distribution by field of IPHR – the proportion to center field increased with each change in configuration. The home run and batting park factor data are shown below in three tables:

Home Runs by Type at Huntington Avenue Baseball Grounds

| Years | Total | OTF | Bounce | IPHR |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1901-04 | 158 | 4 | 1 | 154 |

| 1905-08 | 113 | 20 | 15 | 93 |

| 1909 | 31 | 13 | 9 | 18 |

| 1910-11 | 88 | 47 | 10 | 41 |

Bounce: Bounce Home Runs; IPHR: Inside-the-Park; OTF: Over-The-Fence (Includes Bounce)

Inside-the-Park Home Runs by Field at Huntington Avenue Baseball Grounds

| Years | Total | LF | LCF | CF | RCF | RF | Unknown |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1901-04 | 154 | 15 | 11 | 69 | 35 | 20 | 4 |

| 1905-09 | 111 | 7 | 6 | 60 | 20 | 17 | 0 |

| 1910-11 | 41 | 3 | 1 | 25 | 8 | 4 | 0 |

Batting Park Factors at Huntington Avenue Baseball Grounds

| BA | OBP | SLG | 2B* | 3B* | HR* | BB** |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 101 | 101 | 104 | 71 | 156 | 139 | 105 |

| 97 | 98 | 100 | 89 | 109 | 169 | 100 |

| 95 | 98 | 98 | 103 | 82 | 191 | 108 |

* Per AB

** Per Total Plate Appearance (AB+BB+HP)

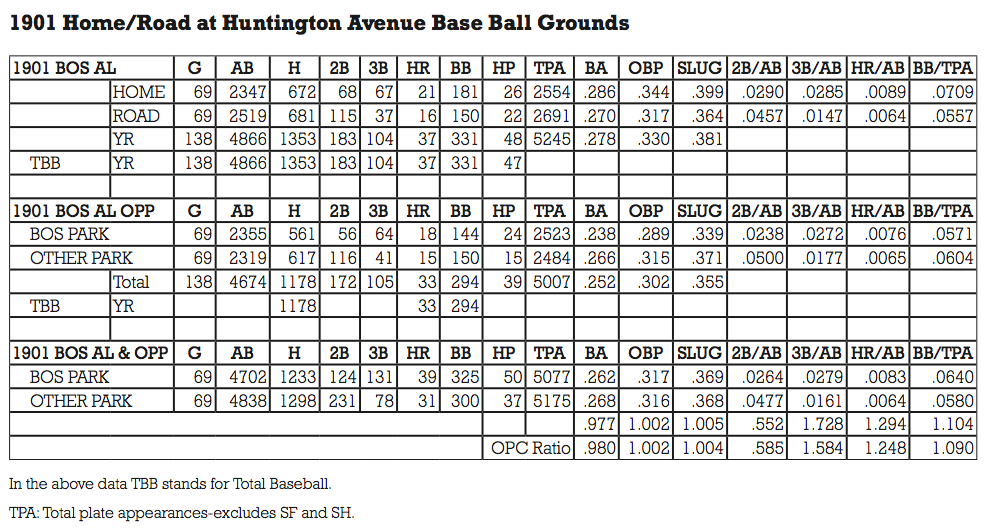

The Home/Road data for 1901 is from the Official AL Day-by-Days:

(Click image to enlarge.)

1901 Home Run Log — Huntington Ave. Grounds

(Click image to enlarge.)

This biography can be found in “New Century, New Team: The 1901 Boston Americans” (SABR, 2013), edited by Bill Nowlin. To order the book, click here.

Notes

1 Alan E. Foulds, Boston’s Ballparks & Arenas (Northeastern University Press Boston MA, 2005), 28.

2 Boston Globe, January 23, 1901.

3 Bill Nowlin, Red Sox Threads (Burlington MA: Rounder Books 2007).

4 Boston Globe, February 3, 1901.

5 Alan E. Foulds, op. cit., 32.

6 Boston Globe, March 29, 1905.

7 Chicago Tribune, September 17, 1909

8 Philip J. Lowry, Green Cathedrals (New York: Addison-Wesley, 1992 ed.), 109.

9 Boston Globe, January 23, 1901.

10 Boston Globe, September 15, 1904.

11 Eric Enders, Ballparks Then And Now (San Diego CA, PRC Publishing Ltd. 2002), 25.

12 Boston Globe, March 29, 1905.

13 Michael Gershman, Diamonds-The Evolution of the Ballpark (Houghton Mifflin Co., Boston MA, 1993), 100.

14 Boston Post, April 9, 1912.