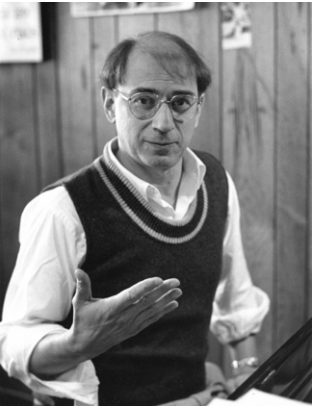

Dave Frishberg

A jazz pianist and songwriter who is known to kids for his contributions to the “Schoolhouse Rock!” series, Dave Frishberg is equally prominent with baseball fans for incorporating his boyhood love of the sport into his music, most notably with the song “Van Lingle Mungo.”

A jazz pianist and songwriter who is known to kids for his contributions to the “Schoolhouse Rock!” series, Dave Frishberg is equally prominent with baseball fans for incorporating his boyhood love of the sport into his music, most notably with the song “Van Lingle Mungo.”

David Lee Frishberg was born on March 23, 1933, in St. Paul, Minnesota. His father, Harry, worked in the clothing business and later bought a men’s store in downtown St. Paul, where his mother, Sarah, worked as the bookkeeper.

Growing up a block from the Mississippi River in St. Paul, Frishberg had three older siblings, a sister, Miriam, and brothers Arnold and Mort (born seven years before Dave). During World War II Arnold was in the South Pacific, and Mort was starting college (he entered the US Navy after the war).

In 1942 Harry took his youngest son to Lexington Park to see the St. Paul Saints of the minor-league American Association. “They were the doormats,” Frishberg said of the Saints. “The first year I watched them, Truck Hannah was the manager, and they ended up in last place. The next year Salty Parker was the manager, and they ended up in last place.”

Despite the losing ways of the hometown team during the war, Frishberg described himself as “a rabid St. Paul Saint fan.” The Saints did better after the war, and in 1946 Frishberg had a special, though brief, role with the team. He had interviewed Dick Siebert, a former major leaguer who was doing the play-by-play announcing for the Saints, and written an article on him for his school’s newspaper.

Siebert, who would soon become the baseball coach at the University of Minnesota and lead the team to three national championships, invited Frishberg to sit in the press box and help him with the broadcasts. “I didn’t know what he meant by help him. What he figured out was that I could be the statistician, the spotter. There was nothing much to spot, because he knew what was happening. But I would keep the stats up to date. I had a little slide rule. If someone got a hit, I would figure out what his average was.”

However, Frishberg’a job lasted only a few games because of a polio epidemic that year, prompting his parents to keep him away from crowds. “I was brokenhearted, but they asked me not to do that anymore. It wasn’t like I had a long relationship with Dick Siebert, but I was impressed with the way he conducted himself and thought he was a nice guy, a real good guy, and a good announcer. I was impressed with the whole thing. I loved sitting there in the press box.It was an interesting place to watch the game. I liked to see the people, what they were doing in the press box.”

Empty to crowded is how Frishberg recalled Lexington Park during and after the war. “My memories are that you could go in there and sit anywhere you want [during the war years]. Then the team got good in the late ’40s, and I remember then the park was crowded.” In 1948 the Saints, by then owned by the Brooklyn Dodgers, made it to the Junior World Series (formerly the Little World Series) against another Brooklyn farm team, the Montreal Royals of the International League.1 “The most excitement in Lexington Park was when the Saints were contenders, and there was hysteria in the park at that time. That’s the year that they went to the Little World Series.

“The Saints are proud of the fact that [Roy] Campanella played on the team and [Duke] Snider played on the team, but they were only there momentarily. The real Saints that stayed season after season were mainly Eric Tipton, a great player, Johnny Dantonio as a great catcher, and the pitchers, Otho Nitcholas and Harry Taylor and Phil Haugstad. They were with the team over a period of time, and they were great stars. Those Dodgers [Campanella, Snider, et al.] were only down for a cup of coffee with the Saints and they were back up quick.”

St. Paul’s rival in the American Association was the Minneapolis Millers, who played in Nicollet Park, of similar vintage to Lexington Park but distinct in that, while the distant fence in right at Lexington was a tough target for left-handed hitters, the opposite was true at Nicollet, where the distance down the line was 279 feet with a high fence with double-decked billboards just beyond that. “I saw one game in Nicollet Park,” said Frishberg. “Minneapolis versus Columbus. I was about 14 and went over there alone. I wanted to see what the hated Millers looked like at home. I wanted to see what the home uniform looked like, and I wanted to see the famous right-field fence. I scoffed when I saw it, of course.”

Despite the rise of the Saints, Frishberg was starting to pay more attention to music than baseball. “I got interested in playing the piano when I was 15. Soon that eclipsed my interest in baseball. I had a year’s worth of lessons when I was a kid, but I never played a lot of classical music, never had a lot of classical chops. I stopped playing while I watched the Saints. When I started playing again it was virtually by ear. I came from a different path than most of the music majors.”

On his web page, Frishberg wrote, “I recognized notes on the staff but I couldn’t read them and execute them quickly. Struggling through piano notation was such an unrewarding process that I lost patience with it. The music died when I tried to read it.”

Frishberg had a couple of mentors, one of them his brother. “If I had a question about music or anything else I naturally went to Mort, who was my adviser and authority about everything.” Another was Jimmy Mulcrone, a co-worker at the Roycraft Company in Minneapolis, where Jimmy’s brother administered the Columbia Records distributorship.

“What Jimmy offered to show me was how to use the piano to deal with music—music theory essentially, or keyboard harmony.” Frishberg said Mulcrone’s lessons “[were] enough to keep me subsequently occupied for years, sitting at the keyboard discovering how to navigate music by using music theory as an expressive tool.”

By the time Frishberg started college, the United States was engaged in another war, this time in Korea. “The idea in those days was to not get drafted. The procedure was stay in college. Plus, join the ROTC, so that when you did have to go into the service, at least you were a commissioned officer—a lot better than being an enlisted man.” ROTC paid for his second two years of college at the University of Minnesota, where he was a journalism major.

“In retrospect, I think I took that journalism major just so I could stay in college during the draft years. I did manage to do it. … It seemed like an interesting way to go and not too difficult. I never paid too much attention to it as a vocation.” Frishberg took electives in the music department. “I wanted to be a music major, but because I wasn’t a legit pianist and had never studied piano, really, I couldn’t be a music major. So I took my electives there and got my major in the journalism school.”

After college, Frishberg served his two years of active duty in Salt Lake City as an Air Force recruiter, “which I thought was kind of ironic because all I wanted to do was get out.”

Done with military obligations, Frishberg moved to New York. “I knew all the time that I wanted to be a bebop piano player, and that’s what I did. I went to New York and became a bebop piano player. … My life was a night life, the world of nightclubs and playing for a lot of jazz groups and ensembles and playing for singers, traveling, and stuff like that.”

Frishberg’s music has been described as “an improbable blend of Hoagy Carmichael, Woody Allen, and Noel Coward.” On the piano Frishberg accompanied jazz and bebop legends like Ben Webster, Bobby Hackett, Al Cohn, and Zoot Sims. He also became a prolific songwriter.

He was later described by Mike Joyce in the Washington Post as a “genuine wordsmith.” In another Washington Post review, Steve Futterman wrote, “He sneaks up on a song, relying on sly, dry wit or plainspoken candor to make his best points.”

On his composing, Frishberg said in 1997, “I don’t know if you can study it, but I will say this. I’m a better songwriter now than I was then. In a way I did study it, tried to make myself better. I learned on the job. I was lucky enough to be paid for being a songwriter, not anything that was ever approaching a hit. All during my life as a songwriter, I’ve been hired to do special assignments, to write special material for television, for instance.” His gimmick is to “write songs for which there is no audience,” and he found his niche by doing what was natural, not what was based on potential for commercial appeal. “I tried to write songs that other people who were hot people would sing. But how could I write those songs? I didn’t believe in them. Ultimately, I found myself writing down to my audience. As a result, what I churned out was inferior. If you don’t mean it, it can’t be good.

“I was always composing. … I became interested in it because I worked for a lot of singers, and I began to get clinically interested in the repertoire. ‘This guy’s good, and this guy’s not that good,’ and what makes Frank Loesser’s song sound so good and so forth. I got interested in songs from an analytical point of view; then began to write them myself.”

In the 1997 interview, Frishberg added, “After I started writing songs that I myself was interested in and let the chips fall, that’s, I think, when I began to be a better songwriter. Now a lot of singers are starting to do my stuff, notably Rosemary Clooney, who did four or five songs in the last couple years—‘Do You Miss New York?,’ ‘Sweet Kentucky Ham.’”

After 15 years in New York, Frishberg moved to Los Angeles to write material for a short-lived television comedy series, and 15 years later to Portland, Oregon. “What prompted me to leave LA was that I couldn’t stand living there any longer. My wife and I now had two sons [Harry and Max], infants, that were born right around the end there. I decided I don’t want them growing up in LA, so we decided to move.” He had always liked Portland, Oregon, and it reminded him of St. Paul, “same kind of people, same kind of towns.”

While still in New York, Frishberg wrote a melody in a Brazilian vein. “This was 1969 when the bossa nova had broke on my consciousness. I had written a couple lyrics for it, and they had nothing to do with baseball. One of them had to do with Richard Nixon, and one of them had to do with a salmon swimming upstream.

“One night, I said, ‘This is terrible,’ and in an idle moment I was looking through the Macmillan Baseball Encylopedia, and one of the names fit right with the musical motif I had. In a flurry I assembled a bunch of names that seemed to go together from a certain era when I was a baseball fanatic.”

Van Lingle Mungo was a pitcher with the Brooklyn Dodgers and New York Giants, known for a great fastball in the 1930s. After arm surgery in 1940, Mungo switched his pitching style and hung on for a few more years, including one with the Minneapolis Millers in 1942, the year Frishberg saw his first game. He dudn’t remember if he saw Mungo pitch, “but I certainly remember his name from seeing the newspaper stories, ‘Millers Get Mungo.’ He was a big name at that time.”

“I was such a baseball nut that every one of those names, I could see they guy’s face. I knew exactly what Augie Bergamo looked like, and I could pick him out of a lineup. The only one I ever saw that I know of was [Eddie] Basinski. He was a Saint. He qualified for the song because he had gone up with the Dodgers and Pittsburgh.”

The same year Frishberg wrote “Van Lingle Mungo,” Jim Bouton wrote Ball Four, a tell-all diary of his 1969 season pitching for the Seattle Pilots and Houston Astros. As a follow-up to the controversy generated by his book, Bouton wrote a sequel, I’m Glad You Didn’t Take It Personally, and in it referred to Frishberg’s new song and how it caused him to contemplate his own writing. “It’s a very pleasant song, sad and haunting,” wrote Bouton. “For the first time, listening to that song, I had some twinges of regret about Ball Four. I felt perhaps a kid reading it would be turned off to baseball heroes that he would never want to write songs about them when he grew up, that he would never feel nostalgic about them. I wondered if I had really smashed heroes, whether I had ruined the game for the kids and ruined it for baseball fans. … And I decided, no, that’s not the way things work.”

Bouton soon switched from pitching to broadcasting and made a video of “Van Lingle Mungo,” displaying photos of the players in the song. However, the video showed Johnny Antonelli, a left-handed pitcher in the 1950s, rather than the John Antonelli that Frishberg had intended, an infielder during World War II.

“John Antonelli’s name is in the song,” Frishberg said in a 2013 interview with Bill Nowlin, “and it’s really uncomfortable because I didn’t realize until later, when it was too late, that there was a more modern John Antonelli, a left-handed pitcher who pitched for the Braves and the Giants. Johnny Antonelli, a left-handed pitcher. I wasn’t talking about that guy at all. The guy I’m talking about in my song was an infielder.

“Later, after the song was out and there was no way to undo it, I realized that the name John Antonelli means different things to different people. It was embarrassing that I would confuse the listeners that way. He was a wartime player. The other guy is a much later guy.”

Frishberg discovered a few other quirks over the years and revised the lyrics. “You have to rhyme it, and I rhymed it quickly, and that’s the first version that came out. Through the years, sitting idly, I’d look and find some names that didn’t fit, weren’t from that era. [Roy] Campanella’s name stuck out. The era I’m talking about there were no black major leaguers. Campanella’s name doesn’t belong in there. I took him out and put in Art Passarella [an umpire].”

In response to comments and inquiries about the song on SABR-L, a listserv of the Society for American Baseball Research (which Frishberg joined in 1984), he wrote, “Imagine my dismay when I subsequently learned that [Bob] Estalella’s name didn’t rhyme in the first place, because it was pronounced as in Spanish: ‘Estaleya.’ So you see, the whole rhyme scheme should have been scrapped, starting with “Danny Gardella,” and now I stand facing humiliation in Baseball Songland. What did I know? I never heard his name uttered, only saw it in print. Same goes for Johnny Gee, whose name I mangled with a soft ‘g.’ There may be other names I’m mispronouncing, but at this stage further corrections would only confuse me.”

Frishberg was invited to sing the song on the Dick Cavett Show, and Mungo was brought in from Pageland, South Carolina. In the waiting room, Mungo said to Frishberg, “You made me famous back home. When do I get the first payment?”

Frishberg said, “I realized he was serious. He thought he was going to get paid.” Frishberg broke the news that he wouldn’t get paid and added, “The only way you can get back at me is write a song called Dave Frishberg. He said, ‘I understand,’ clapped me on the back, and laughed.”

The only other player from the song Frishberg met was Basinski, whom Frishberg had watched play in St. Paul. Basinski later played ten seasons with Portland in the Pacific Coast League and settled in the same city where Frishberg took up residence. “When someone introduced me to Basinski, I eagerly recited the entire starting lineup of his teammates, the 1946 St. Paul Saints, and then tried to explain to him that he was in my song, Van Lingle Mungo.’ Mr. Basinski looked at me like I was from Mars.”

Others weren’t clear about the song, either. Some who approached him thought the lyrics were Portuguese.

“That’s a wonderful song about your childhood friends,” another fan told him. Frishberg said, “I thought, ‘This guy’s hip. He knows exactly what I’m talking about—my childhood friends.’ I was about to compliment him on his acute listening when he says, ‘You know, one of those guys was a ballplayer.’ ”

Frishberg has received requests to substitute other names in place of the ones he used. He said he normally declines. “My answer usually is, ‘If you’re going to do a parody lyric, at least pick a song that everybody knows, not an esoteric piece of music like “Van Lingle Mungo.” “I designed the song as a piece of nostalgia. To modernize that would pretty well nullify it. I don’t consider it a template for baseball players’ names. It just stands by itself as a statement of my own nostalgia for days that are long gone.

“There is something sad about the song, and I think it’s the music but even the text is somewhat sad because there are a lot of forgotten names.”

One request for different lyrics came from the Los Angeles Dodgers. “I convinced them it was a bad idea and ended up writing a new song for them called ‘Dodger Blue,’ ” a paean containing the names of Dodgers after the team moved to Los Angeles. He was at a Dodgers banquet when the song was sung for the first time. “I watched Walter Alston at a table nearby, and I watched a tear come down his cheek and thought, ‘If I can make one ballplayer cry, my life will not have been in vain.’ ”

As of 2013 Frishberg still performed on the piano and lived in Portland with his wife, April Magnusson. He said he kept an eye on the Seattle Mariners, the team closest to him, but was not much of a sports fan. His baseball interest remained in history, and he collected books and sports periodicals from a hundred years ago. His collection included a Reach baseball guide from 1911. “What I look for when I hit the stores when I’m traveling, I’m looking for stuff that’s out of print and from the first part of the century.” “I love the hunt.”

This biography originally appeared in “Van Lingle Mungo: The Man, The Song, The Players” (SABR, 2014), edited by Bill Nowlin. Click here to download the e-book version (free to all SABR members) or to purchase a paperback copy.

Sources

Stew Thornley interview with Dave Frishberg, January 25, 1997, “On Deck Circle” (television show of the Halsey Hall Chapter of the Society for American Baseball Research).

Dave Frishberg telephone interview with Bill Nowlin, August 15, 2013.

Stew Thornley telephone interview with Dave Frishberg, September 18, 2013.

Bouton, Jim, I’m Glad You Didn’t Take It Personally (New York: Dell Publishing Company, 1971), 136-137.

Chapin, Dwight, “Van Lingle Mungo?! Song Lifts Former Dodger Out of Obscurity,” Los Angeles Times, September 12, 1970, D1.

Dave Frishberg web page: http://davefrishberg.net

Futterman, Steve, “The Inimitable Dave Frishberg,” Washington Post, August 22, 2001, C5.

Notes

1 The Saints had a working agreement since 1944 and were purchased by the Dodgers on November 20, 1947. See Joe Hennessy, “Dodgers Purchase St. Paul, Mel Jones Shifted from Royals to Operate Saints,” The Sporting News, November 26, 1947, 19.

Full Name

Dave Frishberg

Born

March 23, 1933 at St. Paul, MN (US)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.