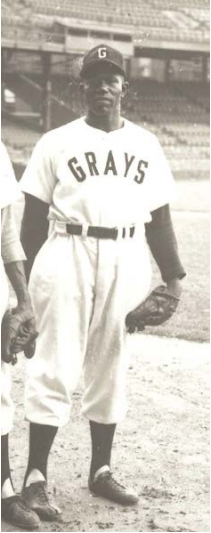

R. T. Walker

Robert Taylor Walker was born on August 20, 1914, in Arboa, Florida. For many years, the legend was that his mother had named him after the actor Robert Taylor, but as the motion-picture star was born just three years before Walker and did not make his movie debut until 1934, that particular tale seems implausible. In fact, teammates often teased Walker about his lack of Hollywood movie-star features, with one player (in the nonpolitically-correct world of the times) describing him as looking “like King Kong.”1

Robert Taylor Walker was born on August 20, 1914, in Arboa, Florida. For many years, the legend was that his mother had named him after the actor Robert Taylor, but as the motion-picture star was born just three years before Walker and did not make his movie debut until 1934, that particular tale seems implausible. In fact, teammates often teased Walker about his lack of Hollywood movie-star features, with one player (in the nonpolitically-correct world of the times) describing him as looking “like King Kong.”1

His countenance aside, Walker was a fairly effective right-handed pitcher, described as having “a good fastball and average control.”2 He also utilized a decent curve and drop pitch, the only off-speed deliveries in his repertoire, and was known as an adequate fielder and baserunner.

Walker was originally signed by the St. Louis Stars in 1944. This version of the Stars was not the same one that resided in the Negro National League throughout the 1920s and ’30s, but rather an independent team that tangled with the likes of the Atlanta Black Crackers and the Jacksonville Red Caps. Already close to his 29th birthday, Walker started two games for the Stars in 1944, completing them both and tossing a shutout in one.3

Since the Stars were an independent franchise, the presidents of both major Negro Leagues agreed that Walker would be a “free agent” at the start of the 1945 campaign, sparking a bidding war between teams eager to sign him. The Homestead Grays made the best offer and Walker became a member of one of the most powerful clubs in professional baseball history.

Though incomplete records make it difficult to know how many appearances spot starters like Walker made, he did have three starts in his first season with Homestead in which he went 1-0 and allowed 12 runs in 23⅔ innings. The highlight of that first year, however, was likely to have been his relief appearance against Honus Wagner’s All-Stars in September in which Homestead beat the barnstorming team, 8-7.

On top of his limited success early in his stint with the Grays, his new teammates were no more sympathetic about the pitcher’s lack of physical appeal than previous players had been: It was here that slugger Josh Gibson chided Walker about his looks and merrily awarded him a spot on his “all-ugly” team.4 Nonetheless, Walker’s value on the field was underscored by the fact that when the team broke camp in 1946, he was one of only three holdovers (along with Garnett Blair and Dave Hoskins) from the previous season’s pitching staff.

That year Walker made two more starts and finished at 2-0, cutting his runs allowed to eight in 24⅔ innings. On June 29, however, the Pittsburgh Courier reported that Walker had been released by the Grays (along with infielder Lick Carlisle and pitcher Jim Haynes) to get the team “down to the 20-man roster.”5

Walker found himself back with Homestead in 1947, however, where he enjoyed his best professional season, starting four times and going 5-1 with three complete games. He gave up 15 runs and struck out 17 batters in 42 innings.

Upon returning to the Grays in 1948, Walker saw limited service, starting only twice and finishing 1-0 while pitching just 20⅓ innings. His career reached its professional summit when the ’48 Grays won the final Negro National League pennant, beating the Elite Giants in the league playoffs, and became the champions of the Negro League World Series by defeating the Birmingham Black Barons in five games.

R.T. Walker started and pitched nine innings in Game Five of the World Series. The Grays scored four runs in the top of the 10th inning to claim a 10-6 victory. After Wilmer Fields entered the game in relief and set the Black Barons down in order in the bottom of the 10th, Walker was awarded the win.

Walker and the Homestead Grays had reached the summit of the black baseball world in what became the last Negro League World Series. But both entities soon became footnotes to history. The Negro National League disbanded at the end of 1948, and the Grays played the 1949 season as members of the Negro American Association; after playing the 1950 season as an independent club, the Grays were permanently disbanded prior to the 1951 season. As for Walker, he remained with the team in 1949, but disappeared into history afterward. Information about Walker’s origins and his life after his playing career appears to have been lost to the historical record.

This biography appears in “Bittersweet Goodbye: The Black Barons, the Grays, and the 1948 Negro League World Series” (SABR, 2017), edited by Frederick C. Bush and Bill Nowlin.

Sources

In addition to the sources cited in the Notes, the author also consulted Baseball-Reference.com and negroleaguebaseball.com.

Notes

1 James A. Riley, The Biographical Encyclopedia of the Negro Baseball Leagues (New York: Carroll & Graf, 1994), 811.

2 Ibid.

3 It was reported by the Pittsburgh Courier on April 1, 1944, that Taylor was sent to the Cleveland Buckeyes of the Negro American League. If this was true, no statistics for Taylor as a member of the Buckeyes exist, nor is there any mention of his playing for Cleveland in any other source.

4 Riley, 811.

5 Pittsburgh Courier, June 29, 1946. Riley’s Biographical Encyclopedia lists Taylor as playing for the Boston Blues at some point during the 1946 season, which conceivably could have been after the Grays’ roster cuts. This Blues team was a member of Branch Rickey’s short-lived U.S. Baseball League, which did not last the year. But as in the case of Note 3, there are no stats or listings for any time Taylor may have spent with this club.

Full Name

Robert Taylor Walker

Born

August 20, 1914 at Arboa, FL (US)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.