Advertising and the Brooklyn Dodgers in 1947

This article was written by Roberta J. Newman

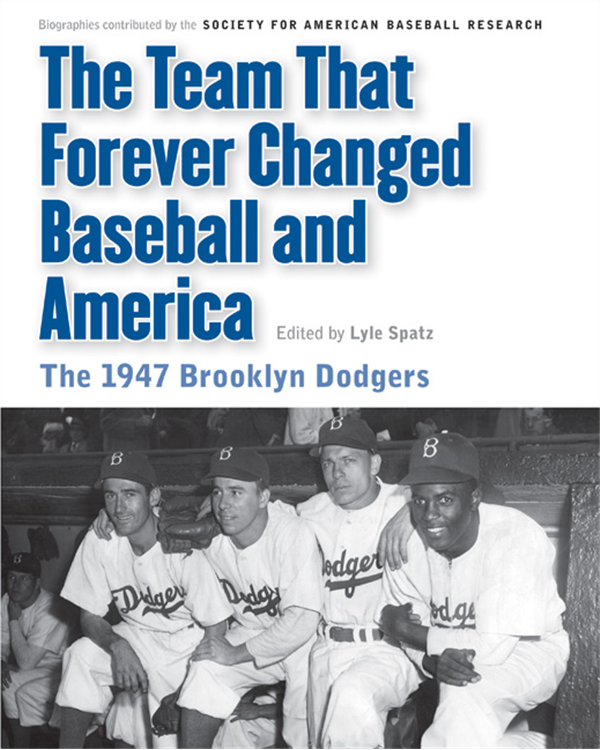

This article was published in 1947 Brooklyn Dodgers essays

The year 1947 was a banner one for the Brooklyn Dodgers. At the same time as the newly desegregated Dodgers seized the National League pennant, the team expanded its appeal to a demographic not traditionally served by organized baseball. It was also a banner year for the advertising industry. With the abatement of wartime shortages, 1947 marked the beginning of a period of unparalleled consumption, fueled by a newly invigorated Madison Avenue. And just as the 1947 Dodgers, both as a real team and as an emblem of a community, would come to serve the advertising industry, so too would the advertising industry serve the Dodgers.

The year 1947 was a banner one for the Brooklyn Dodgers. At the same time as the newly desegregated Dodgers seized the National League pennant, the team expanded its appeal to a demographic not traditionally served by organized baseball. It was also a banner year for the advertising industry. With the abatement of wartime shortages, 1947 marked the beginning of a period of unparalleled consumption, fueled by a newly invigorated Madison Avenue. And just as the 1947 Dodgers, both as a real team and as an emblem of a community, would come to serve the advertising industry, so too would the advertising industry serve the Dodgers.

In order to assess the relationship between the 1947 Dodgers and the advertising industry, it may be instructive to look, however briefly, at the state of American consumer culture, and by extension the state of advertising, at this pivotal time in history. The period immediately following World War II was one of rapid economic expansion. “Economic growth,” writes James T. Patterson, “was indeed the decisive force in the shifting attitudes and expectations in the post-War era.”[fn]James T. Patterson. Grand Expectations: The United States, 1945-1947. New York: Oxford UP, 1996, p. 61.[/fn] “These were above all years of nearly unimaginable consumption of goods,” he notes. “Between 1939 and 1948, clothing sales jumped three-fold, furniture, four-fold, liquor five-fold and household appliances, including TVs, five- fold.”[fn]Patterson, p. 70.[/fn] Given the fact that consumer goods were in short supply during the war, it is not surprising that most of this growth occurred between 1946 and 1948.

But what was behind this postwar consumer frenzy? What induced Americans to spend with abandon? Clearly, a reaction against the deprivations of the Depression and wartime was behind a good part of postwar consumerism. But Americans, accustomed by necessity to frugality, were not in the habit of consuming. They had to be directed to do so. This was the job of advertising, which James B. Twitchell describes as “the culture developed to expedite the central problem of capitalism: the distribution of surplus goods.”[fn]James B. Twitchell. AdCult: USA. New York: Columbia UP, 1996. p. 41.[/fn] And surplus goods there were aplenty, as is generally the case after a major war.

In addition to the postwar surplus that needed to be sold, factories geared up for wartime production had to be put to new use. So, too, was there a need to employ new technologies developed during the war. Taken together, these factors fed what was to become one of the largest producers of culture in America, the advertising industry. In many ways, 1947 was a transitional year for advertising. The “creative revolution” in advertising was still nearly a decade away. But while ads in the print media still resembled those of wartime, they were far more plentiful, as were the goods they sold. At the same time, a new media, soon to become the nation’s primary vehicle for advertising as well as a major durable good, was emerging. Indeed, 1947 may be seen as the beginning of the age of television.

So how did the postwar advertising boom play out in Brooklyn, and more importantly, how did it relate to the Dodgers? Although Brooklynites, like all Americans, had just emerged from a global war, their home, formerly the fourth-largest city in America but always the poor stepsister to “the city,” was essentially provincial, isolated from Greater New York as a whole. A seemingly diverse area, early postwar Brooklyn was really a patchwork of distinct neighborhoods, which Carl Prince describes as a “borough of marbleized ghettoes,” with little in common with one another. Writes Prince:

A corollary to this was the frequently confrontational nature of ethnic relationships in the borough, a hostility that matched the sense of isolation without. The Dodgers formed an ameliorating force for unity in Brooklyn, but the team’s local mystique did not miraculously bring all the people to love each other. Still, the Dodger presence helped.[fn]Carl E. Prince. Brooklyn’s Dodgers: The Bums, the Borough, and the Best of Baseball. New York: Oxford UP, 1996. p. 102.[/fn]

*****

Perhaps the best way to advertise to such a fragmented demographic was to invoke the one element that served to unify it, the Dodgers. As such, the team was featured prominently in local advertising in 1947.

A natural place for the advertising industry to place ads in order to appeal to Dodgers fans was in the borough’s major news organ, the Brooklyn Daily Eagle. In addition to the ubiquitous advertising for Dodgers games, both at home at Ebbets Field and against the archrival Giants at the Polo Grounds, the Dodgers were invoked in nongame-related print ads throughout the Eagle. Naturally, most of Dodgers-related advertising was concentrated in issues from April through mid-October, baseball season, though even in the offseason the Dodgers were never entirely absent from the paper’s advertising pages.

Businesses linking themselves to the Dodgers in the Brooklyn paper were, by and large, local. Lindsay Laboratories and Pharmacy, close by the Brooklyn Academy of Music, for example, welcomed the Dodgers at the outset of the season, urging Eagle readers to drop in to request a schedule of the team’s home games, and presumably to spend some money on health and beauty items, many newly available following the war, and perhaps have a soda at the fountain. And because watching baseball and otherwise consuming was apt to make a person hungry, Lee’s Chinese restaurant, just a stone’s throw from Ebbets Field, trumpeted its proximity to the Dodgers, urging readers to convene there before and after games.

Regional and national advertisers also understood that the way to appeal to Eagle readers, presumably Dodgers fans all, was to allude to the team in their advertising. The Baltimore and Ohio Railroad, freed from wartime travel restrictions, appealed to Dodgers fans who might be planning a foray out of Brooklyn, however briefly, in an ad featuring a cartoon representation of an angry player informing a stone-faced umpire that “we wuz robbed,” followed by rather twisted copy reading, “But Brooklynites say that with pleasure when they discover that B&O rids them of inconvenience, traffic problems and baggage worries.”[fn]Display ad, Baltimore and Ohio Railroad, Brooklyn Daily Eagle, August 11, 1947.[/fn] The makers of Durex double-edge razor blades regularly ran contests in the Eagle, offering free tickets to fans who could describe in twenty-seven words or fewer who was the best player at a given position. While fans of all three teams were invited to enter, Dodgers fans were privileged, Brooklyn’s team always receiving top billing in the Eagle ads.

Regional and national advertisers also understood that the way to appeal to Eagle readers, presumably Dodgers fans all, was to allude to the team in their advertising. The Baltimore and Ohio Railroad, freed from wartime travel restrictions, appealed to Dodgers fans who might be planning a foray out of Brooklyn, however briefly, in an ad featuring a cartoon representation of an angry player informing a stone-faced umpire that “we wuz robbed,” followed by rather twisted copy reading, “But Brooklynites say that with pleasure when they discover that B&O rids them of inconvenience, traffic problems and baggage worries.”[fn]Display ad, Baltimore and Ohio Railroad, Brooklyn Daily Eagle, August 11, 1947.[/fn] The makers of Durex double-edge razor blades regularly ran contests in the Eagle, offering free tickets to fans who could describe in twenty-seven words or fewer who was the best player at a given position. While fans of all three teams were invited to enter, Dodgers fans were privileged, Brooklyn’s team always receiving top billing in the Eagle ads.

Naturally, winning the 1947 pennant brought joy to fans across Brooklyn. It also brought visions of dollar signs to Eagle advertisers. Page after page of ads placed by local businesses filled the Eagle between September 23 and October 2 congratulating the team for clinching a trip to the World Series. Some offered fans souvenirs, others claimed to be the ideal location to celebrate after a Dodgers win, and still others simply linked their names to that of the team, as if to become winners by association. But they all trumpeted their connection to the Dodgers.

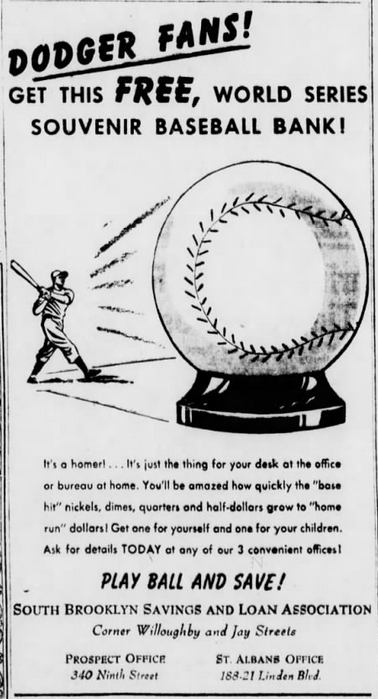

As might be expected in a booming consumer economy, banks competed fiercely for the accounts of Brooklyn’s residents. South Brooklyn Savings and Loan, one of at least a dozen banks to place a congratulatory ad in the Eagle, offered fans a “FREE World Series souvenir baseball bank,” invoking Brooklyn pride with the copy “It’s a homer! It’s just the thing for your desk in the office and the bureau at home.” Not explicitly mentioned, but suggested by the ad copy, is the assumption that once those “base hit nickels, dimes and quarters grow to home run dollars,” the best place for them would naturally be the South Brooklyn Savings and Loan.[fn]Display ad, South Brooklyn Savings And Loan, Brooklyn Daily Eagle, September 25, 1947.[/fn] Not to be outdone, the Williamsburgh Savings Bank, the Brooklyn Trust Company, and the Lafayette National Bank of Brooklyn, as well as the Dime, Fulton, and Roosevelt Savings Banks, all offered their congratulations to the team in the pages of the Eagle.

The Marine Roof of the upscale Hotel Bossert, a few blocks down Montague Street from the Dodgers’ offices, offered itself as a place to “Celebrate our Victory” by “Dancing to the music of Hugo.”[fn]The Bossert, once Brooklyn’s most luxurious hotel, is now owned and operated by the Watchtower as a dormitory for Jehovah’s Witnesses.[/fn] The equally elegant St. George Hotel, home to several of the team’s players during the season, attempted to appeal to Dodgers fans with poetry, of sorts. “Congratulations, Brooklyn team/For every hit and run/You’re in the groove, you’re on the beam/you’ve triumphed, conquered, won,” read its print spot.[fn]Display ads, Marine Roof of the Hotel Bossert, and Hotel St. George, Brooklyn Daily Eagle, October 2, 1947.[/fn] Local saloons and eateries from Bay Ridge to Flatbush, from Fort Greene to Midwood, from Flatlands to Bushwick, places with names like Gallagher’s Subway Inns and the Hole in the Wall, Hoes and the White Shutter, Flynn’s Cabaret, and Hammy’s Pantry urged fans to “Dodge in and Celebrate,” or something of the sort.[fn]Display ads, Brooklyn Daily Eagle, October 2, 1947.[/fn]

Purveyors of consumer goods produced by the repurposed war machine also jumped on the Dodgers bandwagon. Like the Dodgers, Abraham & Straus, Brooklyn’s iconic department store, had a great year in 1947, expanding and adding, among other things, a new furniture department, christened Contemporama.[fn]Jan Whitaker. Service And Style: How the American Department Store Fashioned the Middle Class. New York: St. Martin’s, 2006. p. 315.[/fn] A&S, as it was commonly known, frequently implemented Dodger tie-ins in its advertising, not only at the season’s successful conclusion, but throughout the year. Indeed, earlier in the season, the retailer emphasized its Brooklyn roots by connecting itself to an amateur baseball series, also sponsored by the Eagle and the team, appropriately titled Brooklyn Against the World.[fn]Federated Department Stores, http://www.ohiohistorycentral.org/entry.php?rec=888, July 8, 2009.[/fn] The store’s ad copy reads, “When Brooklyn boys set out to lick the World—look out world,” declaring Brooklyn to be “Dodger Town.”[fn]Display ad, Abraham & Straus, Brooklyn Daily Eagle, September 14, 1947.[/fn] Moreover, A&S would claim agency in the team’s success. “Whee! We’re in! Bring on those Yankees,” screams a half-page A&S ad, as if the retailer naturally was at least partly responsible for winning the pennant.[fn]Display ad, Abraham & Straus, Brooklyn Daily Eagle, September 23, 1947.[/fn]

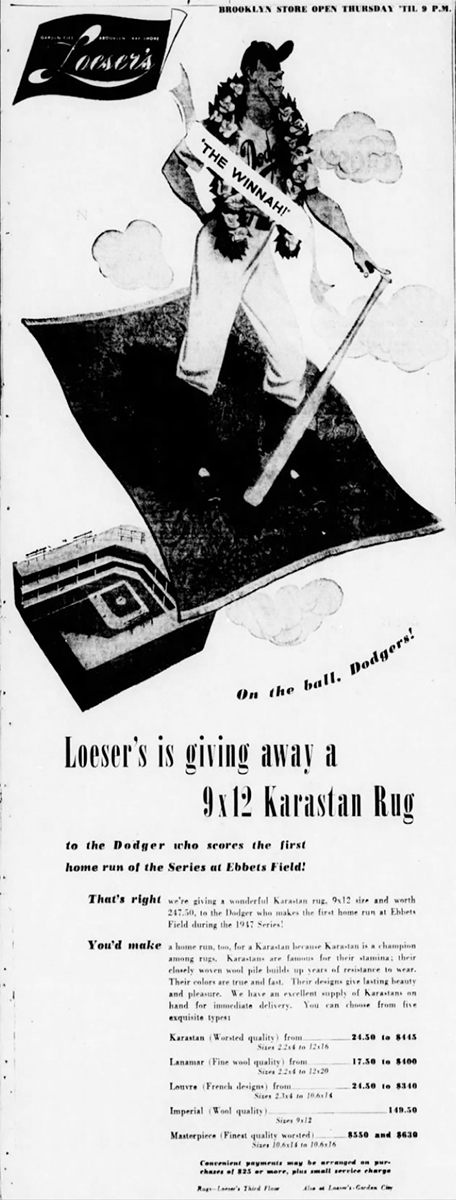

Another downtown Brooklyn department store, Loeser’s, also got in on the act. Taking a page from a discount clothing purveyor and local politician, Abe Stark of Ebbets Field’s “Hit Sign, Win Suit” fame, Loeser’s promised a free nine-by-twelve-foot Karastan rug to the Dodger who hit the first home run of the Series at Ebbets Field.[fn]Display ad, Loeser’s, Brooklyn Daily Eagle, October 1, 1947.[/fn] Of course, Abe Stark placed a congratulatory ad, as well. These major retailers were joined by Bohack Food Stores, a Brooklyn and Long Island grocery chain, which ran a quarter-page ad depicting a gigantic cartoon ballplayer in a Dodgers uniform waving a banner reading “NL Champs,” sitting upon a pile of presumably vanquished National Leaguers, each wearing a cap identifying him as a representative of the other clubs, in front of a brightly shining sun, illuminating the Brooklyn Bridge. The ad asks Eagle readers, “Who’s a Bum?”[fn]Display ad, Bohack Food Stores, Brooklyn Daily Eagle, September 23, 1947.[/fn]

The Eagle was not the only news outlet to benefit from dollars generated by Dodgers-related advertising, especially at World Series time. Ads invoking Brooklyn’s team also appeared in the New York Times and the city’s other media outlets. For the most part these ads did not appeal strictly to Dodgers fans, but invoked the team and its fans in relationship to New York’s other teams. George-Wally Haberdashers and Hatters, located in Manhattan, for example, notes that a featured hat might be “seen at the stadium,” without specifying which of the city’s three major-league ball parks it meant. This ad, claiming that “Whether you’re a Yankee or a Dodger fan, you’re always a winner in this ever popular off-the-face style by Dobbs.”[fn]Display ad, George-Wally Haberdashers and Hatters, New York Times, October 1, 1947.[/fn] The ad appeared in the Times on October 1, and was clearly intended to draw consumers from fans of not one, but two of the city’s teams, capitalizing on the fortuitous occurrence of an all-New York Subway Series. And if a Giants fan just happened in, he too could be the proud owner of a fashionable Dobbs. Unlike the ads in the fundamentally local Eagle, targeted directly at Brooklynites, George-Wally Haberdashers covered all its bases.

The Eagle was not the only news outlet to benefit from dollars generated by Dodgers-related advertising, especially at World Series time. Ads invoking Brooklyn’s team also appeared in the New York Times and the city’s other media outlets. For the most part these ads did not appeal strictly to Dodgers fans, but invoked the team and its fans in relationship to New York’s other teams. George-Wally Haberdashers and Hatters, located in Manhattan, for example, notes that a featured hat might be “seen at the stadium,” without specifying which of the city’s three major-league ball parks it meant. This ad, claiming that “Whether you’re a Yankee or a Dodger fan, you’re always a winner in this ever popular off-the-face style by Dobbs.”[fn]Display ad, George-Wally Haberdashers and Hatters, New York Times, October 1, 1947.[/fn] The ad appeared in the Times on October 1, and was clearly intended to draw consumers from fans of not one, but two of the city’s teams, capitalizing on the fortuitous occurrence of an all-New York Subway Series. And if a Giants fan just happened in, he too could be the proud owner of a fashionable Dobbs. Unlike the ads in the fundamentally local Eagle, targeted directly at Brooklynites, George-Wally Haberdashers covered all its bases.

Given the combined popularity and success of the Dodgers, it is no surprise to find product endorsements and testimonial ads by individual Dodgers players in the pages of the print media, especially in New York. Testimonials were, after all, the meat-and-potatoes of the advertising industry, coming to prominence in the 1920s. Dixie Walker, perhaps the team’s most popular player, endorsed one of the borough’s own home brews, Schaefer Beer, in the New York Times. The testimonial seems to be aimed at New York baseball fans in general, referring to Walker as “baseball’s hardest hitting outfielder” who calls the Brooklyn brew the “finest beer I ever tasted.”[fn]Display ad, Schaefer Beer, New York Times, May 29, 1947.[/fn] Implicit in the ad is the notion that by consuming Walker’s favorite beer, Walker’s fans and other connoisseurs might indirectly share in the player’s talent. Schaefer drinkers needed only to open a cold one to “be like Dixie,” becoming hard-hitters themselves, both literally and figuratively.

Eventually, Schaefer, soon to become known as “the one beer to have, if you’re having more than one,” would cement a major sponsorship deal with the Dodgers organization, but not in 1947. Indeed, it took until 1951 for the brewery to grab a long-desired piece of the Dodgers’ sponsorship pie, the result of Branch Rickey’s reluctance to take money from the beer industry.[fn]Roberta Newman, “Now Pitching for the Dodgers: The Local Character of Baseball and Advertising in Brooklyn, 1890-1957,” in Cooperstown Symposium on Baseball and American Culture 2005-2006, William M. Simons, ed. Jefferson, NC: McFarland, 2007, p. 81.[/fn] The Schaefer sign, with its light-up H for a hit and E for an error, was added to the Ebbets Field scoreboard, right above Abe Stark’s sign, in 1951. Eventually, Connie Desmond, one of the team’s broadcasters, would pitch the brew to the team’s fans. But in 1947 Walker was the sole Dodger to tout the pleasure of quaffing a cold Schaefer.

Although the majority of Dodger-related advertising appeared in the local print media in 1947, occasionally national ads also invoked the team and its players. Once again, Dixie Walker was one of the primary vehicles by which baseball fans and newspaper readers in other cities would consume the Dodgers. In fact, for many Americans outside New York, Walker, through his endorsement advertising, was the face of the Dodgers of 1947. Walker sold Wheaties and Wonder Bread to readers of the Chicago Tribune and the Washington Post. He also pitched Raleigh cigarettes, an endorsement that appears to be counterintuitive on more than one level. That Walker, an athlete and a “role model” to American boyhood, would be paid to claim “New Raleigh 903 is Smoother, Milder, Better Tasting,” seems well-nigh incredible by early twenty-first century standards.[fn]Display ad, Raleigh Cigarettes, Washington Post, July 2, 1947.[/fn] But it was not at all unusual for Walker and celebrity athletes like him to be paid to lend their names and images to cigarette advertising. Neither was it unusual for Walker, a nonsmoker, to endorse a product he did not use. It was not until 1961 that the Federal Trade Commission enforced “Truth in Advertising” laws, mandating that celebrities endorse only products they actually used.[fn]Roberta Newman, “It Pays to be Personal: Baseball and Product Endorsements,” NINE: A Journal of Baseball History and Culture, Volume 12.1, 2003, p. 35.[/fn] The fact that Walker endorsed Raleigh, rather than Old Golds, also appears odd by contemporary standards. Old Golds were, after all, the Dodgers’ radio sponsors. In a clear example of a product tie-in, during Dodgers’ broadcasts a home team home run was an “Old Goldie.” Yet, despite the fact that Walker’s Raleigh testimonial might read as a conflict of interest, neither was it uncommon in 1947 for a ballplayer to endorse a brand produced by his team’s sponsor’s competitor.

Dixie Walker was not the only member of the 1947 Dodgers to endorse products, both locally and nationally. Shortstop Pee Wee Reese, for example, pitched for Rheingold beer, one of Schaefer’s primary competitors in the New York market. But perhaps no single player had a bigger impact on Dodgers-related advertising than the 1947 Rookie of the Year, Jack Roosevelt Robinson. As has been well documented, on April 15 Robinson stepped onto Brooklyn’s playing field, beginning the slow, inexorable process of desegregating major-league baseball. And Robinson’s impact on Dodger-related advertising was nearly as large as his impact on baseball, as a whole.

Naturally, Robinson’s debut had an immediate effect on advertising in the black press. Neighborhoods served by the Amsterdam News, the Chicago Defender, the Pittsburgh Courier, and the Baltimore Afro-American, among other traditionally black publications, grew substantially during the 1940s, the result of a second “great migration” of laborers from the South, seeking economic opportunities and improved living conditions not available in rural regions firmly under the thumb of Jim Crow. Writes James T. Patterson, “This was a massive migration in so short a time—one of the most significant demographic shifts in American history—and it was often agonizingly stressful.”[fn]Patterson, p. 19.[/fn] Instantly, a significant new group of consumers might be reached through Dodgers-related advertising. This demographic differed from the team’s traditional fan base in more ways than one, which is made apparent by the ads intended to appeal to the new target market.

Over the course of the 1947 season, any number of New York businesses targeting African-American consumers linked themselves to Robinson in the pages of the Amsterdam News and the New York Age. Local businesses in Brooklyn’s own rapidly expanding predominantly black neighborhood, Bedford-Stuyvesant, were no exception. The Silver Rail Bar and Grill on Fulton Street, for example, advertised a “Jackie Robinson Gift Party,” noting in parenthetical small print, “Jackie will not appear in person.”[fn]Display ad, Silver Rail Bar and Grill, New York Amsterdam News, August 30, 1947.[/fn] Harlem’s baseball fans were also targeted by local businesses advertising in New York’s black press. Following a Dodgers-Giants match at the Polo Grounds, Bowman’s Henry Armstrong Melody Room at St. Nicholas Avenue and 125th Street invited Robinson’s fans to celebrate with friends at their establishment, though no gift appears to have been involved.

Of course, Robinson’s appeal extended well beyond New York City. Resembling the congratulatory ads for the pennant-winning Dodgers that appeared in the Eagle at the end of the season, page after page of advertising linking local black businesses in other cities with substantial African-American communities across the country also appeared in black newspapers outside New York. A page of ads that ran in the Courier during the Dodgers’ first visit to Pittsburgh is representative of congratulatory advertisements placed in the black press. Vet Sales Company Army-Navy Surplus, Evans Tailors, and Anderson’s Service Stations all invoke Robinson. United Clothing and Furniture Company, offering easy weekly payments, lauds the African-American infielder. More importantly, Virgil H. Lucas and A.A. Lenior, attorneys, tell Robinson, “We’re rooting for you,” in their ad.[fn]Display ads, Pittsburgh Courier, May 17, 1947.[/fn] Each of these ads have something else in common. In every case, the team name is nowhere to be seen. Herein lies a clear distinction between congratulatory ads in the Courier and the other black newspapers and those placed in the Eagle. Like Lucas and Lenior, small local businesses in African-American neighborhoods outside of New York make it clear that it is Robinson, not the Dodgers as a team, with whom they wish to be associated.

Jackie Robinson, like Dixie Walker, also endorsed national products, not only in the black press, but in mainstream print media as well. While Walker sold Wonder bread to white readers of the nation’s papers, Robinson sold Bond bread in the black press, primarily in New York. Not only does Robinson’s Bond endorsement ad, which ran repeatedly throughout the season, include a personal testimonial, it also offers consumers a trade card with an image of the Dodger. “Your grocer will give you a pocket-size reproduction of this Jackie Robinson photograph, free for the asking,” reads the advertisement.[fn]“Congratulations Jackie Robinson,” New York Amsterdam News, August 23, 1947.[/fn] Presumably, while in the market, shoppers would also fill their carts with groceries, including Bond bread.

And like Walker, Robinson, also a nonsmoker, endorsed cigarettes, in this case, the Dodgers’ sponsor, Old Golds, in ads featuring action photographs of Robinson, with facsimile autographs bearing the legend “For a treat instead of a treatment.”[fn]Robinson’s Old Gold ads appeared in a variety of news outlets throughout 1947 and for years after.[/fn] Robinson’s Old Gold ads differ from the local ads in the black press. Not only was Old Gold a national brand, but Robinson’s endorsement appeared in mainstream papers as well as in the black press. Indeed, it might be said that Robinson’s national product endorsements, whose number grew throughout his career, may have led to changes in the way in which African-Americans were perceived by the majority of American consumers. It is, moreover, a little ironic that Robinson and Walker served, individually, as the advertising faces of the 1947 Dodgers. Walker, who initially had opposed Robinson joining the Dodgers, was traded after the 1947 season, while Robinson continued to the advertising face of the team throughout his career.

Throughout the 1947 season, one theme surfaces in print advertising, whether the outlet was black or mainstream, national or local. Wherever the Dodgers had fans, print ads sold televisions. Commercial television, which was introduced during a Dodgers game on July 1, 1941, with a short spot for Bulova clocks, had been halted due to the war, but resumed after hostilities ceased.[fn]James R Walker, Robert V Bellamy. Center Field Shot: A History of Baseball on Television, Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press, 2008. p. 16.[/fn] On March 1, 1947 the Dodgers announced the first agreement by a major-league team to televise all seventy-seven home games, co-sponsored by Ford Motor Company and General Mills.[fn]“Advertising News and Notes,” New York Times, March 1, 1947.[/fn] Ford, along with Gillette, would also go on to sponsor the 1947 World Series.[fn]Walker and Bellamy, p. 70.[/fn] In reality, the impact of television advertising in 1947 was small, as was ad revenue. After all, fewer than one percent of all American households owned sets.[fn]Walker and Bellamy, p. 24.[/fn] A new twelve-inch receiver cost approximately $300.[fn]Walker and Bellamy, p. 26.[/fn] That sum represented ten percent of the median family income in 1947.[fn]Patterson, p. 63.[/fn] Therefore, very few viewers were aware of the poor quality of the commercials shown during Dodgers broadcasts, regular season and World Series alike.[fn]Walker and Bellamy, p. 25.[/fn] Most who saw the games did so in taverns and saloons. But television in 1947 relied on baseball for content. As James Walker and Robert Bellamy write, “The RCA chairman, David Sarnoff observed . . . ’W)e (television makers) had to have baseball games and if they demanded millions for the rights, we would have to give it to them.”[fn]Walker and Bellamy, p. 26.[/fn] “Television did not create baseball,” Walker and Bellamy note, “(b)ut baseball helped to create television. Newly minted television stations were not the only ones that need baseball to fill their broadcast hours. Television manufacturers need appealing programs to push consumers to buy their first sets.”[fn]Walker and Bellamy, p. 26.[/fn]

And sell sets they did. Ads for televisions appeared all over the print media in 1947, especially in New York. Bressner Radio, Inc, offered Eagle readers “a season’s pass to Ebbets Field” with the new DuMont 1947 Teleset. The model, illustrated in the ad, depicts a huge console with a tiny screen. What is on that screen? Of course, it is a crude drawing of the action on the field.[fn]Display ad, Bressner Radio, Inc, Brooklyn Daily Eagle, May 4, 1947.[/fn] Ads for televisions evoking the Dodgers, placed by Davega, a New York area appliance chain, were almost ubiquitous in virtually every regional print outlet during the 1947 season. One Davega ad, published in both the Times and the Amsterdam News, predicted a Yankees-Dodgers World Series as early as August, in an attempt to sell Philco televisions, offering easy installment payments as well as free delivery.

RCA, not to be outdone, placed a full-page ad in the New York Times, making sure consumers were aware of the fact that not only the Dodgers but also the Giants and the Yankees broadcast their home games. RCA’s ad included the promise that “several television cameras strategically located cover the baseball diamond to bring you a close-up of the action wherever it occurs. The engineer can switch from one camera to the other for the best view.”[fn]Display ad, RCA, New York Times, June 1, 1947.[/fn] Why buy any other brand?

In many ways 1947 was the heyday for Brooklyn as well as Dodgers, but changes were afoot. Following the lead of his father, a real-estate developer who fled his Bedford-Stuyvesant neighborhood when an African-American family moved in, Bill Levitt broke ground on Long Island for what would become the largest private housing project in American history. The lily-white subdivision was to be called Island Trees, but the name Levittown stuck.[fn]David Halberstam, The Fifties, New York: Villard Books, 1993, p. 131.[/fn] “Suburbs had long surrounded major cities, but there had been relatively little residential building in the 1930s and early 1940s, and the fantastic sprawl of suburbia was only beginning in the mid-1940,” writes Patterson.[fn]Patterson, p. 11.[/fn] And what did Bill Levitt offer free to new homebuyers in his development?—a television set. Why make the trip to Ebbets Field, when the Dodgers could come to you in the comfort of your brand-new, two bedroom cape or colonial? Indeed, with the breaking of ground in Levittown, white flight from New York had begun. Many of the Eagle’s readers, avid Robinson fans all, would soon begin the exodus out of Brooklyn, headed for Long Island, New Jersey, and points west. Ten years later, the Dodgers would follow.

In many ways Dodger-related advertising, a sign of postwar prosperity and consumerism, may be seen as a bellwether for what was to come. The team’s fans would retreat into their new homes, complete with their Contemporama furniture and labor-saving appliances purchased at A&S, not the one in Brooklyn, but in the store’s branches in New Jersey and on Long Island. They would watch Jackie Robinson steal home in Game One of the 1955 World Series on RCA televisions, perhaps purchased at Davega’s. Still, the mark of these wholesale changes, which may be traced to the early postwar years, would not be truly felt for nearly a decade. Unlike the 1955 Dodgers, the 1947 Dodgers did not win the World Series; nevertheless, it most certainly was a great year for Brooklyn, its team, and Dodger-related advertising.

ROBERTA J. NEWMAN is a cultural historian who has written extensively on sport and the media. She is currently working on a coauthored book-length project dealing with the last days of segregated black baseball. A lifelong Brooklynite, she is a member of the faculty of New York University’s liberal studies program.