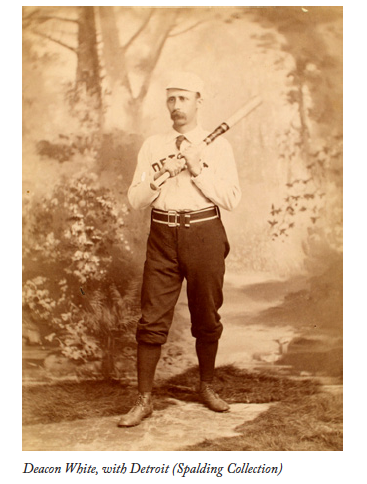

Deacon White: An Overlooked 19th Century Legend

Editor’s note: In 2010, SABR’s Nineteenth Century Research Committee selected Deacon White as its Overlooked 19th Century Baseball Legend. This article first appeared in the committee’s Fall 2010 newsletter. In December 2012, the Veterans Committee elected White, along with former Yankees owner Jacob Ruppert and longtime umpire Hank O’Day, to the National Baseball Hall of Fame.

James Laurie “Jim” White was born on December 2, 1847 in the small town of Caton, New York. He grew up with two future major league players, his brother Will and his cousin Elmer.

James Laurie “Jim” White was born on December 2, 1847 in the small town of Caton, New York. He grew up with two future major league players, his brother Will and his cousin Elmer.

White stated that he learned to play baseball from a Union soldier returning home from the Civil War in 1865. White, later nicknamed “Deacon” for his virtuous life, calm demeanor and his leadership on the field, was one of baseball’s first superstars. He began his playing career with the Forest City Baseball Club of Cleveland in 1868 while working for McNairy, Claflin & Co. He immediately became their best player, spending most of his time behind the plate as the team’s catcher. He would occasionally pitch and once gained notoriety for shutting out the famed Eckfords of Brooklyn with his controversial wind-up motion.

The Forest City Club joined the National Association in the league’s inaugural season, playing in the league’s first game against the Fort Wayne Kekiongas. In the first inning of that first game, White doubled off Bobby Mathews for the first “major league” hit. Considered to be one of the first catchers to move up under the batter, White was the premier catcher of the 1870s.

Playing without a glove, he caught more games (409) than anyone else during the decade while being one of the game’s most feared hitters. The tall, slender ballplayer had a long reach, soft hands and was often called catlike and energetic behind the plate. As a batter, White won two batting titles (.367 in 1875 and .387 in 1877) and three RBI crowns (1873, 1876 and 1877).

In 1873, White became a member of the Boston Red Stockings that went on to win the championship in 1873, 1874 and 1875. Boston’s famed “Big Four” of Ross Barnes, Cal McVey, Al Spalding and White moved onto the Chicago White Stockings in 1876 and won the first NL pennant. Spalding and “The Cat” were the top battery in the game in those early years of professional baseball, second to none.

In 1877, Harry Wright lured White back to Boston. Playing mostly as a first baseman and outfielder, White, along with Jim O’Rourke and Tommy Bond, led the team to another pennant. From 1878 to 1880, he played for Cincinnati, forming a battery with his brother Will, before joining Buffalo for five seasons. By 1882 he was a regular third baseman and a member of the second famous “Big Four” with Dan Brouthers, Hardy Richardson and Jack Rowe. In 1886, the Buffalo franchise was purchased by the owner of the Wolverines, bringing the “Big Four” to Detroit. In 1887, the Wolverines, with White hitting .303 at the age of 39, won the NL pennant and defeated St. Louis of the American Association to become world champs.

White finished his career with Detroit in 1888, Pittsburgh in 1889 and Buffalo of the Players’ League in 1890. White’s career totals include 1,140 runs, 2,067 hits, 988 RBI, a .312 batting average and just 221 strikeouts. His 162 game average includes 215 hits, 118 runs and 103 RBI.

White died on July 7, 1939 as the oldest living former major leaguer in St. Charles Township, Kane County, Illinois, twenty-five days after the first National Baseball Hall of Fame induction ceremony in Cooperstown, New York. His final resting place is Restland Cemetery, in Mendota, Illinois. White appeared on the National Baseball Hall of Fame’s 2009 Veterans Committee ballot for pre-1943 players but failed to gain election, receiving five of the necessary nine votes for election.

Although White has not been elected to the Hall of Fame, he has received high praise from his contemporaries and historians have expressed support for his entry into the National Pastime’s ultimate shrine. Albert Spalding called him the greatest natural catcher he ever saw. Similar comments were made by Henry Chadwick and his onetime batterymate Pud Galvin, among others. In The Bill James Historical Abstract, James named White the most-admirable superstar of the 1870s. Baseball historian Joe Overfield wrote a piece for Baseball Digest in the May 1957 issue entitled “The Men the Hall Forgot.”

In this article, he champions the election of Pud Galvin, Billy Hamilton, Sam Thompson, Roger Connor, Tim Keefe and Deacon White. Only White has not been inducted. Catcher: How the Man Behind the Plate Became an American Folk Hero, by Peter Morris, chronicles the early history of the catcher. White is featured prominently throughout the book and should be a must read for future Veterans Committee voters. In 1986, Jim White did receive some recognition when he was inducted into the Buffalo Baseball Hall of Fame.