Global World Series: 1955-57

This article was written by Bob Buege

This article was published in Spring 2012 Baseball Research Journal

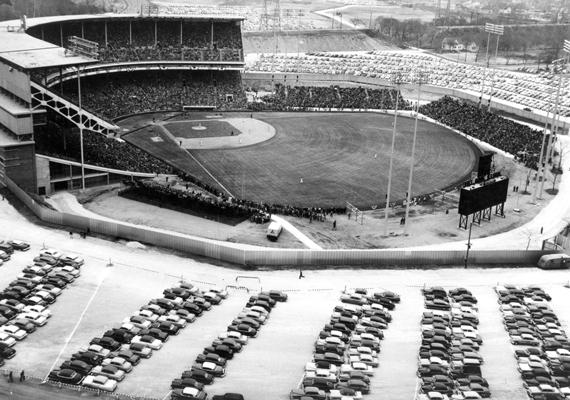

Milwaukee County Stadium was in its third season as home of the National League’s Braves when it hosted the inaugural Global World Series in 1955. (Courtesy of the Milwaukee Brewers)

Half a century before there was a World Baseball Classic, there was the Global World Series. The scars of World War II had not yet fully healed, but teams representing four continents and three island nations chose to set aside their political differences and do battle with a bat and ball between the white lines. The idea of an international baseball competition was not original. Ray Dumont founded the National Baseball Congress in 1938 and later created the national semipro tournament held annually in Wichita, Kansas. On May 30, 1948, Dumont conferred in St. Louis with J.G. Taylor Spink, publisher of The Sporting News, who also served as global commissioner of the NBC. Also attending the meeting was Alejandro Aguilar Reyes, Mexican commissioner for the Congress. The three men met to discuss an annual non-professional world’s baseball championship series.1

For whatever reason, the planned competition did not reach fruition. However, in 1950 a Japanese all-star team comprising mostly college ballplayers hosted a best-of-seven-game inter-hemisphere championship series in Tokyo and Osaka. The young Japanese athletes were eager to test their skills against players from other countries. Mindful, no doubt, of the pre-war baseball tours of the likes of Babe Ruth and Lefty O’Doul, they naturally turned to the United States. Their opponents were the winners of the 32-team United States semipro championship tournament held in Wichita. In 1950, as in the three previous years, that team was the Fort Wayne (Indiana) Capeharts.

Perhaps more interesting than the baseball games were the timing and location of the competition. The series took place from September 10 through September 15, 1950, barely five years after the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, while thousands of U.S. soldiers still occupied the islands of Japan. What’s more, the opening game was played less than three months after the outbreak of the Korean War, with President Truman authorizing General Douglas MacArthur to use American troops from the Japanese occupation to fight against North Korea. Travel to Japan was not yet normalized, so to expedite the series, all of the ballplayers were sworn in to active military duty during their stay.

The opening day festivities were delayed by a brief and fortunately mild earthquake. When the ground finally stood still, General MacArthur’s wife threw out the first ball. Former Chicago Cubs shortstop Salvador Madrid belted two home runs and led the Americans to an easy 6–1 victory.

On leave from the Boston Braves, he dominated the Japanese in two games of their five-game series with the Fort Myer Colonials. (National Baseball Hall of Fame Library)

In 1950 the perpetually strong Fort Wayne ballclub featured a pair of southpaw hurlers that the Japanese batters found unhittable. Patricio “Pat” Scantlebury and Jim “Lefty” LaMarque were both all-star veterans of the Negro Leagues, LaMarque having led the Negro American League in ERA just two years previous, and Scantlebury having been selected for East-West All-Star games in 1949 and 1950.

The talented Fort Wayne team took the series quite handily in five games. Their ballclub had overwhelming pitching and power. They might have had even more power. Legendary sandlot and minor league slugger Joe Bauman had been invited to join the Capeharts for the Japanese series. In 1954 Bauman slammed 72 home runs for Roswell in the Class C Longhorn League. He declined Fort Wayne’s offer to compete in Japan because he needed to work at his Texaco station along Route 66 in Elk City, Oklahoma.

The only game the host team won in the series was Game Three. Japan won, 1–0, in 12 innings when several of the American players were disabled by severe food poisoning.

On September 15 the Capeharts wrapped up their successful visit to the Far East by defeating the Japanese team, 6–1, behind series Most Valuable Player Pat Scantlebury. Meanwhile 750 miles to the west, across the Sea of Japan and the Korean peninsula, troops of the U.S. 10th Corps made a surprise amphibious landing at Inchon, directed personally by Douglas MacArthur.

Two years later the Korean War was still raging. In September 1952, the U.S. Navy introduced a new form of aerial combat. From the aircraft carrier Boxer they launched pilotless Grumman F6F Hellcats equipped with heavy explosives, in effect creating guided missiles to strike targets in North Korea.

War or no war, the International Baseball Congress again sponsored a Japanese-American series in Tokyo in September 1952. The U.S. representative this time was a service team, the Fort Myer Colonials, from the military district of Washington, D.C., adjacent to Arlington National Cemetery.

Fort Myer’s opponents never had a chance. The Colonials simply had too much pitching. In the series qualifying Fort Myer for the national tournament, for example, former Boston Braves bonus baby Johnny Antonelli fired a one-hitter and fanned 18 batters, not to mention slamming two triples and a single. Fort Myer overwhelmed Sherman Athletic Club of Charleston, 21–0.

In the Wichita tournament from August 15 to September 1, the Colonials swept all seven of their games, defeating six service teams and the Wichita Boeing Bombers. Antonelli won three of them. St. Louis Cardinals pitcher Tom Poholsky also won three, and future Pittsburgh Pirates hurler Bob Purkey and Jacksonville (Sally League) right-hander Chuck Fowler combined to win the other. The only game that was close was the championship contest, a 5–4 victory over Fort Leonard Wood of Missouri.

Besides their major league pitchers, the Fort Myer team also boasted New York Giants catcher Sam Calderone and Pittsburgh Pirates shortstop Danny O’Connell. O’Connell was voted Most Valuable Player among the 32 tournament teams.

Following their championship in Wichita, the Fort Myer ballclub flew to Hawaii for four exhibition games. Subsequently they continued on to Tokyo and took two out of three from the Japanese all-stars in the inter-hemispheric series. After that they traveled to Osaka and took two straight to wrap up the series championship, four games to one.

Fort Myer hammered the hosts in the series opener, 13–5. Future Milwaukee Braves Sam Calderone and Danny O’Connell each blasted a three-run homer and Calderone added a solo shot to lead the assault. In Game Two O’Connell provided all of the offense with a two-run home run in support of Antonelli’s four-hit, 2–0 shutout. The Japanese club earned its only victory in the third game, beating the Americans, 8–4, despite home runs by Calderone and O’Connell.

Game Four was a hard-fought 2–1 win for the Colonials, but the fifth game was a blow-out. Antonelli won for the second time in the series behind a 17-hit attack. Calderone, who was voted the series MVP, smashed a grand slam to highlight a convincing 9–1 American triumph.

“We took the team to Japan for the international series,” Albert B. (Happy) Chandler, president of the International Baseball Congress, said proudly, “and won four out of five games.”2

A.B. “Happy” Chandler aspired to be U.S. President. Instead he became Commissioner of Baseball and later president of the International Baseball Congress.

Chandler was a former U.S. Senator from Kentucky and the Commissioner of Baseball following the death of Kenesaw Mountain Landis. Having replaced Spink as head of the IBC, Chandler was looking to expand the Japan-United States competition to a series involving four nations, or perhaps eight, in 1954. Japan had successfully hosted two series with the U.S. team, but in order to increase the number and scope of the teams in the tournament, Chandler felt that a more centralized location was necessary, i.e., an American city. He also knew that someone had to underwrite the cost and be willing to absorb possible financial loss.

Seeking a possible host city, Chandler visited Milwaukee in mid-August 1953. The Braves were out of town, playing the Cubs in Wrigley Field that day. Their starting pitcher was Johnny Antonelli. Chandler, though, traveled to County Stadium to confer with Dick Falk, Wisconsin’s commissioner of semipro baseball, and to watch the Badger State’s teams try to qualify for the national tournament in Wichita.

“Milwaukee is the talk of the baseball world,” Chandler said. What’s more, County Stadium impressed him as a perfect venue. “The playing field is ideal and this is one ballpark that has its fences at equal distances along the foul lines,” he noted.3

Brooklyn Dodgers president Walter O’Malley had already volunteered the use of Ebbets Field for a world tournament. Chandler’s ideal site, however, had two prerequisites: a hard-charging, energetic local host to oversee the tournament, and a large and enthusiastic fan base. In Dick Falk and the baseball-crazed patrons of County Stadium, Chandler found both.

Falk had served as a Marine Corps officer in World War II. He was a member of a prominent Milwaukee family, a civic leader and the secretary and assistant to the president of the Falk Corporation, a manufacturer of industrial gears in Milwaukee since 1895. Since 1939 he had also been the Wisconsin Commissioner of the National Baseball Congress, appointed by Ray Dumont. Falk was a tireless, loyal advocate of ballplayers and the game of baseball, the perfect man to direct the first Global World Series.

Falk and the IBC were unable to organize the first series in time for their intended 1954 date. Instead they staged the inaugural Global World Series September 23–28, 1955, after the Milwaukee Braves had completed their home schedule.

The cost of putting on an ambitious tournament was considerable. Falk managed to round up more than 100 local businesses as sponsors in order to stage a first-rate event. Every team’s delegation was given an elaborate welcome as it arrived at Mitchell Airport. The teams passed beneath a flower-covered arch and onto a red carpet as they stepped down from the airplane. Each team received this royal treatment except the group from Puerto Rico, who arrived nearly five hours ahead of schedule and found no one to greet them. That night a one-hour parade through downtown Milwaukee kicked off the festivities with marching bands, drum and bugle corps, giant inflated balloons, and colorful floats.

The eight teams participating in the inaugural Global World Series spanned the globe, representing the continents of North America, South America, Asia, and Europe, plus Central America and island nations in the Pacific and the Caribbean. They spoke a variety of languages. The Colombians deplaned with only one English-speaking person, and that person was sick. The Japanese interpreter was asked how his country’s players would be able to argue with the umpires without speaking English. The answer was simple: “We never argue with the umpire.”4

As might be expected, the American entry was the overwhelming favorite to win the championship. The ballclub representing the host nation was the Boeing Bombers from Wichita, Kansas, who had defeated the Sinton (Texas) Oilers in the national tournament. The Bombers were led by former New York Giants infielder Daryl Spencer, a Wichita native serving an Army hitch at Fort Sill, Oklahoma. Spencer, the Most Valuable Player of the recent national tournament in Wichita, had been added to the Bombers roster. Except for Spencer and two former employees, everyone in the Bombers lineup worked at Boeing assembling B-47E Stratojets and B-52 Stratofortress bombers. All of them had minor league baseball experience.

The other North American ballclub in the tournament hailed from Canada. The Edmonton Eskimos had won the Western Canada League championship, but for reasons known only to them, they refused to accept five ballplayers from other league teams added to their roster, as required by their league rules. As a result, the Eskimos were disqualified and replaced by the club they had defeated, the Saskatoon Gems, most of whose players had competed in collegiate ball in the United States.

Somewhat surprisingly, a decade after the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, the team that was the clear fan favorite was the Japanese Kanebo All-Stars. Maybe it was because they had traveled so far to get to County Stadium, or perhaps because their players were so short and so polite. Japan’s team lacked power, but every one of its players was a .300 hitter.

The Puerto Rican Baricuas, an all-star team from the best league on their island, were piloted by a manager familiar to many Milwaukee baseball fans. He was Luis Olmo, a former Brooklyn Dodger who had played the outfield for the Milwaukee Brewers in Borchert Field in 1951. Most of the Puerto Ricans had played winter ball with or against big leaguers like Bob Buhl and Sad Sam Jones. They presented a powerful lineup and were considered a title threat.

The Refinerias from Mexico were the perennial champions of the Poza Rica League in Central Mexico. This league had sent Bobby Avila to the major leagues. Avila won the American League batting crown in 1954 while hitting .341 and leading the Cleveland Indians to an amazing record of 111–43. Baseball had a long history in Mexico, although teams customarily played their games only between Thursday and Sunday.

The mountainous South American nation of Colombia has a capital city, Bogota, situated at such high altitude that it rarely gets warm enough for baseball. The Colombians played ball in the small towns closer to sea level. Their hitters were not powerful, but their infielders were collectively the finest in the field.

The delegation from Hawaii included perhaps the biggest celebrity at the tournament, but he was not a baseball personality. Duke Kahanamoku, the sheriff of Honolulu, had been the 100-meter Olympic swim champion in 1912, repeating in 1920. Hawaii was not a part of the National Baseball Congress because it was still a U.S. territory four years from statehood. The Honolulu Red Sox ballplayers, though, disliked being called “Hawaii,” comparing it to calling the Boeing Bombers “The United States Mainland.”5

The final entrant in the tournament was the European champion, the Spanish National All-Stars. They had a history of being Europe’s best, but they were in reality a weak ballclub. Until recent years they had played baseball on soccer fields, with the rules adapted to compensate for the restrictions of the playing environment.

On Friday night, September 23, 1955, the first Global World Series got underway in Milwaukee County Stadium. The stadium lights were turned off and a spotlight shone on the Great Lakes training center band as they marched in and played the U.S. national anthem. Then the chorus of the Cudworth American Legion post sang “The Battle Hymn of the Republic.” The lights were turned back on, and all eight teams, in uniform, lined up along the baselines and were introduced. Finally, the baseball began.

The opening game matched the Saskatoon Gems and the Japanese Kanebos under a cool autumn sky. Japan scored two runs in the top of the first, but they never scored again off Canada’s Charlie Bogan. Meanwhile the Canadians scored four times in the bottom of the first, paced by a home run by first baseman Jim Ryan, to give Bogan all the runs he needed. In the fifth inning the Gems also pulled off a triple play, the first ever in County Stadium. The Japanese club tried everything, including the use of three different third base coaches in the eighth inning, but Canada defeated Japan, 5–2.

The next day featured a full slate of four games. The afternoon’s first contest quickly became the most entertaining of the week. The Milwaukee Journal described it aptly as “a comedy in six and one-half acts.”6 The Hawaii Red Sox overwhelmed the team from Spain, 23–0, in a game that was not as close as the score would suggest. The tournament had a “mercy rule” terminating any game in which a team was losing by eight runs or more after seven innings.

Spain’s hitters were obviously ineffective, but their greatest deficiency appeared to be pitching. Their starting hurler, Pedro Seda, threw softly and had no curve ball. As a result, by the time he was relieved in the fourth inning, he had allowed 14 runs and 12 hits while walking six, hitting three batters, and letting go of four wild pitches. His teammates were also charged with five errors though in reality they probably had twice that number. After the game was halted, the enthusiastic Spaniards sprinted across the diamond and joyfully shook the hands of their Hawaiian rivals. Later, when asked why his manager left him in so long, Seda replied, “He had confidence in me.”7

In the day’s second game Colombia surprised Puerto Rico’s Baricuas, 5–3, defeating their mound ace, Kelly Searcy, who had recently signed a contract for 1956 with the Baltimore Orioles. While the Colombian infield performed admirably, Searcy’s teammates betrayed him with five errors. Most members of the Puerto Rico team had not played baseball since the end of winter ball in February. The effects of their inactivity were visible.

The Boeing Bombers met Mexico in the evening’s first game. If the U.S. team was expecting a cakewalk, they were disappointed. They scored first, but the Refinerias answered with a three-run inning. After nine innings the score was tied at four apiece. It remained that way until the 12th inning. With a runner on second and one out, Minor Scott came to the plate. Scott had played seven seasons of minor league ball, including a short stint as Eddie Mathews’s infield mate with the Atlanta Crackers.

Mexico’s pitcher, Rafael Pedroza, was in the process of walking Scott intentionally when the feisty hitter reached out and lined an outside pitch to right field. The runner scored from second, touching off a five-run rally that gave the Wichita team a 9–4 victory. In the night’s last competition, the Hawaii Red Sox, who had not been challenged at all by Spain early in the afternoon, earned their second win by beating the team from Canada, 5–2.

On Sunday the Mexican ballclub rebounded from their tough loss to the U.S. team by clobbering the Puerto Rican team, 7–2, dealing Luis Olmo’s guys their second defeat in the double-elimination format. Mexico’s relief pitcher Ramon Brown entered in the third inning and held Puerto Rico to just one hit the rest of the way.

Japan eliminated Spain, 8–0, on a pitching masterpiece by right-hander Kasuo Fukushima. He came within one out of a no-hitter in a game ended after seven innings by the eight-run rule. Ironically, the only hit came from pitcher Pedro Seda. Maybe that’s why his manager had confidence in him.

Canada, meanwhile, put Mexico out of the tournament with a 5–1 triumph nearly overshadowed by Mexico’s fine shortstop, Miguel Fernandez, who owned three of his club’s four hits, plus a stolen base and consistently brilliant defense.

The final Sunday night game presented two un-defeated teams, the Bombers from Wichita against the Colombians. Western League veteran Mike Werbach, formerly in the Brooklyn Dodgers organization, pitched the complete game and received all the support he needed on offense from Daryl Spencer, who tripled with the bases loaded in the fifth inning, as the host team defeated the club from South America, 5–3.

The following night two teams met who were both on the brink of elimination. In the tourney’s best pitching battle, Colombia’s Enrique Hernandez outdueled Japan’s Sadao Kawai, winning 1–0. Hernandez also drove in the only run with a double in the second inning, thus eliminating the popular Japanese team.

Also Monday night the U.S. team took on their territorial cousins from the former Sandwich Islands. The Boeing club defeated Hawaii, 5–3, beating 32-year-old Dartmouth College graduate Jim Doole. After Bombers starter Jim Upchurch failed to locate home plate consistently with his pitches, Vern Frantz relieved him and allowed just three hits in the last six and two-thirds innings to earn the victory.

On Tuesday night the tournament field was whittled to two. As expected, the American team ousted the Saskatoon Gems, 8–2. Jim Morris hurled a six-hitter and received slugging help from two former New York Giants, outfielder Les Layton, who homered, and shortstop Daryl Spencer, who tripled. Canada’s loss put them into Wednesday’s consolation game against Colombia.

The Colombians were consigned to the third-place contest by a 13–0 thrashing at the hands of the Hawaii Red Sox. Sox pitcher Len Kasparovitch, a 36-year-old Honolulu foot patrolman, allowed only three hits as the islanders easily earned a meeting with the Wichita Bombers.

The Saskatoon Gems led off Wednesday evening with a 4–3 win over Colombia to gain a third-place finish in the first Global World Series. That set the table for the anticipated coronation of the champion as the undefeated Boeing Bombers faced the once-defeated Hawaii ballclub. After three innings the outcome seemed a foregone conclusion. Wichita led, 6–0, and the only suspense was whether Boeing’s Mike Werbach would throw a no-hitter.

In the sixth inning, though, the Red Sox broke the hitting drought in a big way, scoring five runs off Werbach and relief man Delos Smith. In the seventh inning Hawaii catcher Sol Kaulukukui’s bases-loaded single drove home two runs to give his team an unlikely 8–6 victory over the team from the mainland.

The surprise win by Hawaii delayed the championship game until Thursday night. Once again the Bombers seized an early lead, 4–0, in the top of the third inning. Again, the Hawaiians rallied to tie the game. Wichita reliever Vern Frantz held the Sox scoreless for the final eight innings of an 11-inning ballgame. Kasparovitch matched him until the 11th. In the final frame the Boeing team used four bases on balls, two of them with the bases loaded, to score three runs and escape with a 7–4 victory over the gritty Hawaiians. It was a struggle, but the Wichita Boeing Bombers reigned as the 1955 Global World Series champions. Len Kasparovitch of the runner-up team was named the Most Valuable Pitcher, and Daryl Spencer of the winners was voted the Most Valuable Player.

The weather throughout the tournament had been cold and sometimes wet. Expenses far exceeded expectations, and attendance at County Stadium was disappointing. Nevertheless, the series was declared a success by everyone involved, and plans began at once for the 1956 event.

In reality the 1956 Global World Series champion was decided during the week before the international competition began. In the U.S. National Semipro Tournament in Wichita, Kansas, the top American teams battled each other for the right to represent their country. The favored teamed was the Texas Alpine Cowboys. It would not be an exaggeration to describe them as the prohibitive favorite.

The Alpine Cowboys boasted three star ballplayers. Their starting catcher, Clyde McCullough, had played 15 years in the big leagues, most recently with the Chicago Cubs until he was released on July 27. (His backup was Milwaukee native John Kloza Jr., whose father had played for the St. Louis Browns.)

Most prominent were the Cowboys pitchers. Lefty Johnny Podres was a member of the world champion Brooklyn Dodgers. In fact, he was the MVP of the 1955 World Series. He was given leave and allowed to play semipro ball in 1956 while serving in the U.S. Navy, stationed at Norfolk, Virginia. Right-hander Jack Sanford was on leave from the Army. He was destined to make his debut with the Philadelphia Phillies three days after the Global World Series ended. In 1957 he won 19 games for the Phillies and was the National League Rookie of the Year.

The Milwaukee Sentinel was so sure of the national tournament’s outcome that they printed a photo of Podres with the caption, “Former Dodger Ace Headed for Global Series.”8 This was the Milwaukee paper’s equivalent of “Dewey Defeats Truman.” Despite their big-name ballplayers, however, the Alpine Cowboys lost in the semi-finals in Wichita. The tournament winner and U.S. representative was the Allen Dairymen from Fort Wayne, Indiana.

The Dairymen lacked big-name star-power, but all of them except two had played minor league ball. One who had not was shortstop John Kennedy, a veteran of the Negro Leagues who, the following April, would become the first African American to play for the Philadelphia Phillies. The other was Don Pavletich, a recent graduate of Nathan Hale High School in the Milwaukee suburb of West Allis. After school let out, Pavletich had signed a $35,000 bonus contract with the Cincinnati Redlegs. Pavletich, who would ultimately play a dozen years in the big leagues as a catcher and first baseman, was added to the Fort Wayne team’s roster for the Global World Series.

As in 1955, the ballclubs from Colombia, Mexico, and Puerto Rico were all-star squads primarily comprising winter league stars. The European champion this time was from Holland, known as the Honkballers. They were reputed to be far superior to last year’s Spanish entry. The Canadian representative was the North Battleford Beavers. The Japanese team was the Nippon Oil Cal-Tex club from Yokohama. The only holdover was last year’s runner-up, the Honolulu Red Sox from America’s future fiftieth state.

Hope springs eternal and the international teams visiting County Stadium were no exception. The manager of the Hawaii Red Sox, Larry “Peanuts” Kunihisa, said, “We were just a couple of outs from the title last year, so we plan to claim it this time.”9

As soon as he got off the plane, Canadian baseball commissioner Jim Robison told reporters, “We finished third last year, and we’re here with a more balanced club for this tourney.”10

Mexican commissioner Salvador Mondragon called his country’s representative “by far the best ever assembled” in Mexico, “100 percent improved at every position.”11

Through an interpreter, Japanese manager Masuyama exclaimed proudly, “Our team has strengthened its batting power and therefore feels more confident of its chances.”12 His team wasted no time in proving itself, although they did so more with finesse than with power.

On Friday night, September 7, in the tournament’s opening game, the ballclub from Yokohama played spectacular defense throughout but still had to come from behind in the ninth inning to edge Canada, 5–4. The Japanese rally consisted of a walk, a bloop single to right, a bunt single, a sacrifice fly, and a perfectly executed suicide squeeze.

Saturday featured a tripleheader involving the other six tournament teams. In the afternoon the Fort Wayne Dairymen led off by defeating Hawaii, but not easily. The U.S. club scored four runs in the first inning on four singles and an error. They added a fifth tally in the second inning when shortstop John Kennedy stole home. After that the Dairymen failed to score. The Hawaiians, trailing 5–3 going into the ninth, loaded the bases with no outs against starting pitcher Walt Wherry. Pete Olsen came in to relieve Wherry and escaped unscathed by striking out the first two batters and getting the final out on a grounder to the shortstop.

In the evening’s first game, Puerto Rico overwhelmed the Dutch “Honkballers,” 14–2, in a game shortened to six and a half innings by the 12-run-advantage mercy rule. Despite losing badly, the players from Holland lined up after the game, faced the Puerto Rico dugout, doffed their caps, and bowed deeply toward their conquerors. The Dutch defeat was not surprising. They had never before played a game under the lights, nor had they ever played on a regulation diamond.

Mexico rallied from a 4–0 deficit in the sixth inning to beat Colombia, 8–5, in the night’s finale. Eduardo Beltran earned the victory with three strong innings in relief for Mexico.

In the first Sunday afternoon game, Colombia outfielder Carlos Bustos slammed the first home run of the series to lead his club to an easy 7–1 victory against Holland. The Honkballers played better in the field than they had Saturday, but they managed just three base hits, struck out nine times, and were eliminated.

Also making a hasty exit were the North Battleford Beavers from north of the border. Hawaii hurler John Sardinha, formerly of the U.S., allowed them only three hits, all of them by third baseman Curt Tate, in a 10–1, eight-inning contest. The loss dropped Canada from the tournament.

Both Sunday evening games matched undefeated teams. The Allen Dairymen milked a three-run second inning and a two-hitter from lefty Pete Olsen and coasted to a 6–2 triumph over Puerto Rico. The U.S. team recorded only five base hits of their own but added nine bases on balls from the generous Puerto Rican pitcher.

The night’s most fan-pleasing performance came from Japanese pitcher Motoji Fujita. Standing just five and a half feet tall and weighing at most 130 pounds, the little right-hander completely baffled the free-swinging Mexico team. He gave up only three hits and struck out 15 in a 5–0 whitewash. Fujita had pitched seven and one-third against Canada on Friday night without allowing an earned run. The Yokohama ballclub narrowly missed another thrill for the crowd when Yu Hanai, often called the “Babe Ruth of Japan,” hit a high drive off the top of the 355-foot sign in right field, inches short of a home run.

The biggest shock of the tournament was delivered on Monday afternoon. Although grossly overmatched in size and strength, the Japanese team out-hustled, out-pitched, and out-scored the American club from Fort Wayne, 6–3. The Asian visitors were simply the more aggressive ballclub, as evidenced by the fact that when they won the coin toss, they elected to bat first. The Japanese manager said that it reflected his team’s desire to be on the attack. He felt that the American custom of choosing the last bats was a sign of a defensive attitude.13

Milwaukee sandlot player Don Pavletich gave the U.S. team a 2–0 lead in the second inning by smashing a triple to the fence in center field, then scoring on a sacrifice fly. The Americans added another run in the third.

Japan scored twice in the fifth inning, though, then tacked on four more in the sixth with daring base-running augmented by several U.S. errors. Meanwhile relief hurler Sadayoshi Osawa worked six and one-third shutout innings to gain a 6–3 victory. The American defeat left Japan as the only team in the tournament without a loss. Osawa’s joyful teammates hoisted him onto their shoulders in tribute.

The two evening games were decided by late rallies and each one eliminated the losing club. Mexico scored two runs in the top of the seventh and held on for a 4–3 win over Puerto Rico. The Hawaii Red Sox were scoreless until the seventh inning when Shin Yogi belted a solo home run over the left-field fence. The Red Sox still trailed, 2–1, going into the bottom of the ninth. The Watanabe brothers, Riki and Tsune, both singled, as did pitcher Vane Sutton, to tie the score. Colombia’s 19-year-old pitcher, Edgardo Venegas, then balked in the winning run for Hawaii.

The Fort Wayne team ousted Mexico the following night. The Dairymen led by just 2–1 when they came to bat in the bottom of the fifth. Suddenly they blew the game open with a four-run burst in the inning, then terminated the contest early via the mercy rule with seven runs on seven straight line-drive hits in the bottom of the sixth for a 13–1 decision. Mexico tried a series of pitchers but with no success. Third Baseman Jim Higgins and second baseman Ed Wopinek each drove in three runs for the winners.

Tuesday’s nightcap produced another surprise. Hawaii and Japan each called on their ace hurler, and each pitched heroically. For Hawaii, Len Kasparovitch fired a six-hit shutout, aided immeasurably by five double plays from his infielders. Motoji Fujita worked the complete game and gave up just five base hits, but unfortunately for him, his Hawaiian rivals manufactured two runs, one scoring on a sacrifice fly and the other on a squeeze bunt, for a 2–0 Red Sox victory.

As a result, the teams from the U.S., Japan, and Hawaii each showed one loss. They drew lots to determine which two clubs would play each other, with the bye team playing the winner for the championship. The Allen Dairymen drew the bye, so the Wednesday night game was a replay of Tuesday, Hawaii vs. Japan.

In these days of pitch counts and five-man rotations it seems impossible, but Motoji Fujita, who pitched the complete game the previous evening, started the game for Japan. He had nothing left, though. The Hawaiians belted him for four runs in just over two innings. The three subsequent relief men did no better, and the Yokohama infield made six errors. The Red Sox from the islands took a 9–1 lead into the ninth inning. Japan bunched three hits off John Sardinha and scored a pair of consolation runs, but the Yokohama Nippon Oil team finished in third place after a 9–3 pounding.

For the second year in a row, the clubs from the U.S. and Hawaii met for the Global World Series title. Hawaiian manager Peanuts Kunihisa sent five-foot four-inch junk-ball artist Cris Mancao to the mound. The Dairymen’s skipper, John Braden, called on 22-year-old southpaw Pete Olsen, who stood more than a foot taller than his pitching rival. Both pitchers performed admirably.

Olsen shut out the Red Sox on three hits. Mancao only gave the Americans six hits in six and one-third innings, but for the Dairymen it was enough. Shortstop John Kennedy singled in the first inning, went to second on an errant pick-off throw, and scored on a base hit by Wilmer Fields. That turned out to be the winning run. The Dairymen tacked on an insurance run in the seventh and held on for an exciting 2–0 victory. The sparse crowd of 2,637 was disappointed— they rooted for the Hawaiians—but the U.S. repeated as champions.

Despite the high level of competition that the tournament offered, ticket sales for the second year in a row were meager. The baseball mania surrounding the Milwaukee Braves had not transferred to the semipro series played in County Stadium, but rather overshadowed it. In 1957, therefore, the venue was changed to Detroit’s Briggs Stadium, home of the Tigers, where attendance averaged half of Milwaukee’s. The only change in the list of competing nations was the substitution of Venezuela in place of Puerto Rico.

For the third straight year the series opener matched the teams from Japan and Canada. On Friday the 13th of September, the two clubs battled through 13 tension-packed innings. Against three Japanese pitchers, the Canadian team from Edmonton managed only one run through 12 innings. At the same time, Ralph Vold, the Canadian hurler, who had labored for five years in the low minors of the Brooklyn Dodger organization, worked all 12 innings and allowed a single run. In the top of the 13th Canada scored an unearned run to take a 2–1 lead.

In the bottom of the inning, Vold, who had retired the last 19 hitters, suddenly could not find the plate. He walked three batters, one of whom he picked off first base, and gave up a short single to load the bases. With two outs, Japan’s first baseman, Yuji Takenouchi, sliced a liner off right-fielder Joe Riney’s glove, driving in two runs and producing a 3–2 Japan win.

The Saturday afternoon game was a blowout with, as usual, the European representative on the losing end. The new kids on the block from Venezuela punished the Netherlands nine, 13–2. For the South Americans, Panteleon Espinoza slammed a bases-loaded double and Fernando Basante belted two home runs, the only batter to do so in Global World Series play.

The American representatives in the series were the Plymouth Oilers from Sinton, Texas, the first club from the Lone Star State ever to win the national semipro title. The Oilers added two other ballplayers to their tournament roster, both from the Wisconsin champion, the Falk Corporation team from Milwaukee. Slugging outfielder Paul Schramka, a cup-of-coffee player with the Chicago Cubs in 1953, had impressed the Oilers with a long home run in the Wichita tournament. The other Milwaukeean, right-handed pitcher Arnie Campbell, had won 12 games while losing just once during the season.

The U.S. team’s first opponent was Colombia, led by young hurler Edgardo Venegas. Schramka tripled to greet Venegas and drive in the game’s first run in the top of the opening inning. Single runs in the next two frames put the Oilers ahead, 3–0, but the Colombians tied the score in the eighth on a two-run homer by Dagoberto Lopez. The game went to the tenth inning tied, 3–3. With one out Schramka slammed his second triple. Clint Hartung, 35-year-old former New York Giants phenom who both pitched and played right field in the Polo Grounds, singled Schramka home with the lead run. Wilmer Fields put the game on ice by blasting one off the second deck, and the Texans ended up on the plus side of a 6–3 margin.

Saturday’s final outing became a pitchers’ duel between Perry of Hawaii and Flores of Mexico. Each threw a complete-game four hitter. With the help of two Hawaii errors, though, Mexico prevailed, 3–1.

Sunday presented all eight teams in action, beginning with the Sinton Oilers versus another oil producer, Venezuela. The Latin team featured fancy-fielding shortstop Manuel Carrasquel, 19-year-old brother of Chico Carrasquel, the four-time all-star from the Chicago White Sox who was the first Latin-American all-star in the major leagues. Arnie Campbell took the mound for the U.S. team and shut down the South American club. He had a no-hitter for four innings and for six frames did not allow a ball to be hit out of the infield. With relief help from Howard Reed with two outs in the eighth, Campbell shut out the Venezuelans, 3–0. Clint Hartung singled and doubled and drove in one of Sinton’s runs.

Johnny Podres, the 1955 World Series hero, failed to qualify his team for the Global World Series. (National Baseball Hall of Fame Library)

The tournament’s two weakest competitors were quickly eliminated on Sunday. Canada soundly defeated the Holland club, 8–2, behind lefty Blaine Sylvester from the University of Utah. Canada scored four times in the first inning and cruised to an easy win. Hawaii then drubbed Colombia, 13–0, in a mercy-rule game shortened to six innings. Larry Kamishima smashed two home runs for the victors.

Sunday’s most exciting game was its last, a seesaw affair between Japan and Mexico. Japan scored first; Mexico tied them. Japan scored three in the third to jump ahead, 4–1. Mexico tallied one in the third and two runs in the fifth, and it was tied at four apiece. In the seventh, though, Japan scored what proved to be the winning run in a 5–4 decision, giving Mexico its first loss.

The first two games on Monday eliminated two more ballclubs from contention. The team from Edmonton, Alberta, outslugged the Hawaii Red Sox, 11–6, to send them home to their island paradise. The winning pitcher for Canada was Ernie Nevers, nephew of the legendary football star of the same name who in 1929 scored 40 points in a game against Red Grange and the Chicago Bears.

In the day’s second contest, Venezuela dispatched Mexico, 3–2, the second one-run defeat for the unlucky team from south of the border. Mexico led, 2–1, until the eighth inning when pinch hitter Luis Boyer, with two outs, doubled home Fernando Basante and Miguel Martinez to make Venezuela the winner and disqualify Mexico.

Monday night’s late game saw the only remaining undefeated nations, the United States and Japan, square off. In the second inning the Oilers allowed the Japanese club to put two men on base, one by catcher’s interference and one by an unsuccessful fielder’s choice. Pitcher Shiro Shimazu then doubled home both runners for a 2–0 lead.

Clint Hartung promptly tied the score for the U.S. with a two-run homer, his second blast of the series. Japan took a one-run lead in the last of the third, and Shimazu made it stand up until the eighth. He had help from the Americans, though. In the fifth inning, U.S. pitcher Parnell Hisner was on first base when Paul Schramka belted a long double to the wall in right-center. Hisner sprinted around third and safely reached the plate with the tying run. The problem was, he had failed to touch third base.

With one out in the eighth, Schramka singled, Wilmer Fields doubled, and the Texas team was back in business. Unfortunately for them, Shimazu was replaced by Takashi Suzuki, who retired the next two batters on a pop-up and a strikeout. The final score was 3–2, and Japan had its third straight one-run victory.

The showdown between the North American teams occurred on Tuesday night. To say that the game’s outcome was shocking would be a wild understatement. The two-time defending champion United States team, whose country invented baseball, not only lost but also suffered the ignominy of the mercy rule as their game was shortened to seven innings by the score of 8–0. Twenty-year-old southpaw Dale Ziegler, a college kid from the University of Southern California, silenced the Plymouth Oilers sluggers and surrendered just one base hit, a single by Jim Higgins. Meanwhile the Canadians pounded Dave Baldwin and Arnie Campbell, scoring five runs in the third and three runs in the fourth, to put the game out of reach and the United States out of the tournament.

Japan, the only undefeated team in the tourney, didn’t stay that way for long. In the evening’s second ballgame, Venezuela surprised the Japanese club with three-hit pitching from Francisco Cirimele and an inning of scoreless relief from Valentin Arevallo. Venezuela scored three runs in the second inning, all they needed for a 3–0 win.

So then there were three. Canada, Venezuela, and Japan entered the tournament’s final doubleheader deadlocked for first place. In the first game, Canada continued its winning ways by trouncing Venezuela, 5–1. Ernie Nevers pitched the complete game. The victory earned the Edmonton club the right to meet Japan’s Constructors for the title.

The 10,457 paying customers at Briggs Stadium received their money’s worth and then some. As usual, the crowd threw its support solidly to the players from Japan. Canada scored a run in the third inning and added another in the sixth. Ralph Vold held Japan scoreless until team captain Sadayoshi Osawa smashed a solo home run in the seventh to make it 2–1.

In the ninth inning, down to their final out, Japan rallied again, and again it was Osawa to the rescue. He doubled to drive in the tying run and send the game to extra innings.

In the 11th Canada’s third pitcher, Mike Blewett, lived up to his last name. He walked two batters, including Osawa, then surrendered a line-drive single up the middle by second baseman Masayuke Furuta, scoring two runs. Takashi Suzuki shackled the Canadians in the bottom of the inning, and Japan had a 4–2 triumph and the first non-American championship of the Global World Series.

For the vanquished Oilers of Sinton, Texas, the only honors were individual. Clint Hartung and Wilmer Fields earned selection to the all-tournament team, as did the two players borrowed from Milwaukee Falk, Paul Schramka and Arnie Campbell. Schramka was voted the top outfielder in the series.

And so it ended. Everyone close to the tournament agreed that it was a wonderful event that deserved to be continued. Attendance, however, had been only marginally better than in Milwaukee, and financial losses again were large. Dick Falk and members of the International Baseball Congress tried mightily to revive the tournament in 1959, but it was not to be. The Global World Series was destined to enjoy only a three-year life span and then disappear into the annals of history.

Milwaukee native BOB BUEGE was born the day before Bob Feller no-hit the New York Yankees. Bob (Buege, not Feller) has attended every SABR Convention since 1990. He is the author of “The Milwaukee Braves: A Baseball Eulogy” (1988) and “Eddie Mathews and the National Pastime” (1994). He is currently writing a history of Borchert Field, Milwaukee’s minor-league ballpark from 1888–1952.

Notes

1 “Dumont, Reyes Confer on International Series,” The Sporting News, June 2, 1948, 22.

2 “Hap Chandler Likes the Stadium; Talks About World Meet There,” Milwaukee Journal, sec. III, August 16, 1953.

3 “Hap Chandler Likes the Stadium; Talks About World Meet There,” Milwaukee Journal, sec. III, August 16, 1953.

4 “Hotel ‘Goes International’ as Global Ball Stars Arrive,” Milwaukee Journal final edition, September 21, 1955.

5 Bob Teague, “Hooks and Slides,” Milwaukee Journal, Sports sec., September 25, 1955.

6 Bob Teague, “Hooks and Slides,” Milwaukee Journal, Sports sec., September 25, 1955.

7 “Spanish Pitcher Has Rough Time,” Milwaukee Journal, sec. 2, September 27, 1955.

8 Milwaukee Sentinel, sec. B, September 2, 1956 (caption, photo of Johnny Podres).

9 Gene Tackowiak, “Four Lay Claim to Global Title,” Milwaukee Sentinel, sec. 2, September 6, 1956.

10 Gene Tackowiak, “Four Lay Claim to Global Title,” Milwaukee Sentinel, sec. 2, September 6, 1956.

11 “US and Hawaii Will Tangle in Top Global Series Opener,” Milwaukee Journal, sec. 2, September 2, 1956.

12 Tackowiak, “Four Lay Claim.”

13 Tackowiak, Reliefer Allows Three Hits for Winners, Milwaukee Sentinel, sec. 2, September 11, 1956.