Home Run Derby: A Tale of Baseball and Hollywood

This article was written by Don Zminda

This article was published in The National Pastime: Endless Seasons: Baseball in Southern California (2011)

It was just the top of the first, and Willie Mays hit four home runs before Mickey Mantle could even step to the plate. Decades before it invaded the All-Star Game, Home Run Derby sprouted in the fertile soil of Hollywood.

It was just the top of the first, and Willie Mays hit four home runs before Mickey Mantle could even step to the plate. Decades before it invaded the All-Star Game, Home Run Derby sprouted in the fertile soil of Hollywood.

Home Run Derby was filmed at L.A.’s Wrigley Field, former home of the Pacific Coast League Los Angeles Angels and soon to become the first-year home of the expansion L.A. Angels of the American League. But to fans unfamiliar with PCL baseball, the park was a mystery. The show’s host, Mark Scott, never mentioned the name of the park or its Southern California location. And that seems curious, because Home Run Derby was an L.A.—and Hollywood—production through and through.

Mark Scott was more than just the host of Home Run Derby; he was one of the creators of the show. Born in Chicago in 1915, Scott excelled in track, baseball, and basketball, but a knee injury suffered playing football at the University of Illinois ended his athletic career. He began working in broadcasting and landed his first baseball play-by-play gig in Norfolk, Virginia, where he did re-creations of major league games by day and live minor league games at night. In Virginia, Scott met his wife, Dorothy, and on a late honeymoon in Havana, Cuba, in 1951, he ran into J.G. Taylor Spink, publisher of The Sporting News. Scott was looking for a higher-level announcing job, and Spink suggested he contact Bob Cobb, owner of the Hollywood Stars of the Pacific Coast League (and also owner of Hollywood’s famous Brown Derby Restaurants). Scott landed a job as the Stars’ play-by-play announcer beginning in 1952.1

Scott quickly became a well-known figure in the Hollywood/Los Angeles scene. He did Stars games and was sports director at radio station KFWB, announcing boxing matches, horse and dog races, and hosting a daily 15-minute radio show, “Mark Scott’s Pressbox.” When the Dodgers brought major league baseball to Los Angeles in 1958, Scott became host of the “Meet the Dodgers” television show.2

This being Hollywood, Scott became friends with many people in the entertainment business, and before long he was supplementing his broadcasting career with occasional acting gigs, usually appearing as a broadcaster or narrator. Among his film credits were The Kid From Left Field, Killers from Space, The Harder They Fall, and a cameo role in Somebody Up There Likes Me, a sports bio-pic with Paul Newman as boxer Rocky Graziano.3 The cast of Somebody Up There Likes Me also included a young ballplayer-turned-actor named Michael Dante, who had played for several years in the minor leagues under his given name of Ralph Vitti. Scott and Dante became good friends.4

Another of Scott’s entertainment-industry colleagues was Hollywood veteran Lou Breslow. A writer, producer, and director with a long history in both movies and television, Breslow had worked on films featuring the Marx Brothers, Laurel and Hardy, Abbott and Costello, and the Three Stooges, among others. While he had mostly worked in comedy, Breslow had also dabbled in sports films. In the 1930s he wrote several short films that featured Babe Ruth.5

By the late 1950s, Breslow was working mainly in television, and during that time, he came up with the idea for Home Run Derby.6 The premise of the show was simple. Each week, two major-league sluggers would face off in a home run hitting contest that would last nine “innings.” A home run counted as a run, but any batted ball that failed to reach the seats, as well as any taken pitch that was called a strike by the umpire, was considered an out. With that format, each contest could easily be completed in a half hour.

Breslow shared his idea with Scott and a few TV production people, and the group formed a company, Homer Productions. Breslow would be the show’s producer, with Scott serving as host as well as helping do much of the work needed to bring their brainchild to the screen.7

While Home Run Derby seemed like a promising idea, it wasn’t the kind of show likely to appear on one of the three major television networks. So Breslow, Scott, and their colleagues turned to Ziv Television Productions, a company which specialized in distributing weekly first-run shows to local stations across the country. At its peak in the mid-1950s, Ziv was producing more than 250 half-hour television episodes annually.8

Ziv shows were known for tight production schedules and modest budgets,9 and Breslow, Scott, and company did their best to make Home Run Derbyan economical operation. Prize money for the ballplayers consisted of $2,000 for the winner of each show and $1,000 for the loser, with a $500 bonus for any player who hit three straight home runs without making an out. That was pretty good money in those days as the World Series winner’s share in 1960 came to $8,417.94.10 But, it wasn’t overly generous by TV standards, and Homer Productions found other ways to keep their costs down. Apart from a small production and camera crew, the show featured only Scott, a plate umpire and two foul-line umps, two pitchers, a catcher, and a few people to shag balls in the outfield. Costs for use of Wrigley Field were held down by filming two episodes a day. Contestants were usually flown into Los Angeles the day prior to an episode, then flown back home the night of the shooting unless the player was a returning champion.11

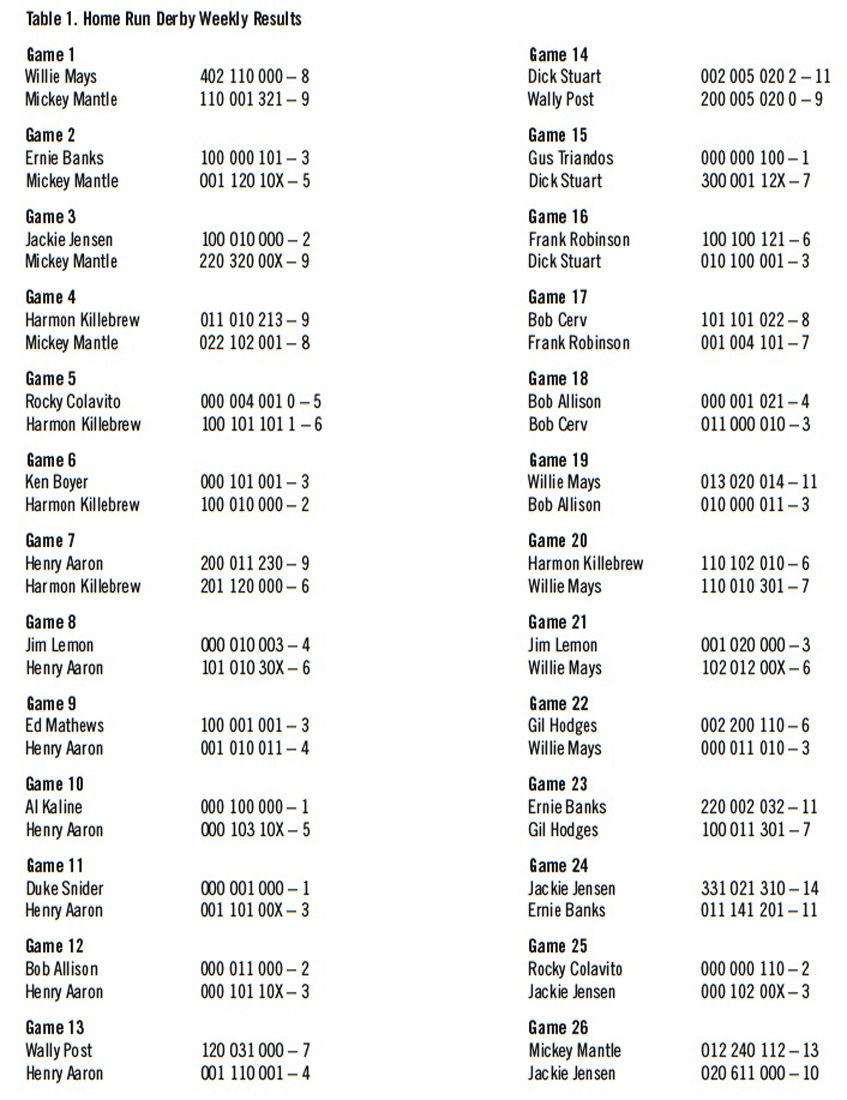

Table 1: Weekly Results

(Click image to enlarge)

Scott used his personal contacts to line up the pitchers, catchers, and umpires who worked on the show. One of the pitchers was Tom Saffell, a former major league outfielder who had played for the Hollywood Stars during Scott’s term as the club’s broadcaster. Behind the plate was Eddie Malone, who had caught for Hollywood 1952–54.12 Art Passarella, the plate umpire, was a former American League arbiter (1941–42, 1945–53), who, like Scott, dabbled in acting. Passarella had appeared in the movie version of the Broadway hit Damn Yankees and the Ziv-produced television show Sea Hunt.13 He would go on to numerous acting roles in the years following his umpiring stint on Home Run Derby—most notably as Sergeant Sekulavich in the Karl Malden/Michael Douglas police show, The Streets of San Francisco.14

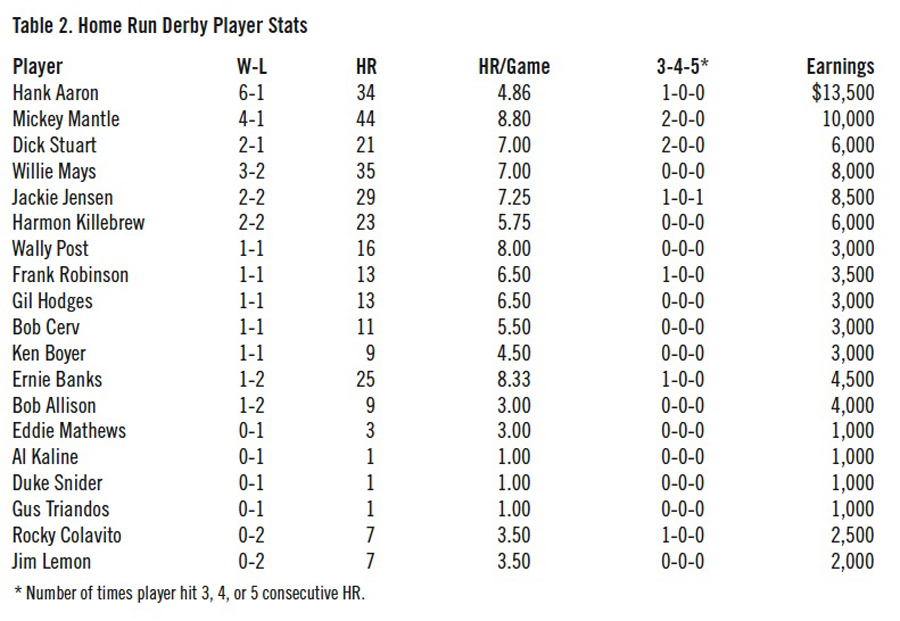

Scott proved remarkably successful at lining up the contestants. Of the 20 players who had hit 25 or more home runs during the 1959 major league season, all but four (Joe Adcock, Orlando Cepeda, Woodie Held, and Charlie Maxwell) would appear on Home Run Derby. Fifteen of the 16 major league teams were represented. The missing club, the American League champion Chicago White Sox, had no players with more than 22 home runs in 1959. Nine of the 19 competitors would be elected to the Baseball Hall of Fame.15

Home Run Derby began filming in December. Working on its two-episodes-a-day schedule, the 26 contests were completed in a three-week period.16 Scott would open each episode by describing the rules of the game and introducing the players. “Gentlemen, today you’re going for the big money,” he would say. While one competitor took his licks, the other would sit behind the plate engaged in conversation with Scott, who also described the action. Controversy was religiously avoided. When one of the more flamboyant players of the era, Dick Stuart, appeared on the show, Scott made a point of saying, “Dick, you know and I know differently, but a reputation got out that you were somewhat of a pop-off guy. It’s enlightening for people to see you here and see that you’re like any other ballplayer—you like your base hits, but you’re not a braggart.” Stuart responded by admitting that “a few years ago I did say a few offbeat things, but I learned the hard way.”17

But if the commentary could be a little bland, the contests themselves were usually entertaining. In the series-opening clash, Mays led 8–2 after the top of the sixth inning, but Mantle—batting right-handed despite the fact that he was facing a right-handed pitcher—fought back to win the game, 9–8, with a homer in the bottom of the ninth. Mantle would go on to defend his crown by defeating Ernie Banks and Jackie Jensen before losing episode four, 9–8, to Harmon Killebrew.18

Home Run Derby hit the airwaves in April 1960, coinciding with the start of the major league season.19 While Scott had his share of critics,20 his simple approach would, for many, become one of the show’s charms. As David Gough wrote many years later, “When we watch the program today … we can still sense Scott’s enthusiasm for the game and his desire to infect his listeners and viewers with a similar appreciation.”21 The show proved popular with fans, and there seemed little reason to doubt that Ziv would bring back Home Run Derby for a second season in 1961.

But it was not to be. Tragically, Mark Scott died of a heart attack in Burbank, California on July 13, 1960—about halfway through the syndicated run of the show’s first season. He was only 45 years old.22 Without its host and driving force, the show was not renewed for a second season, and Home Run Derby disappeared from the airwaves.

Table 2: Home Run Derby Player Stats

(Click image to enlarge)

Remarkably, Home Run Derby would return to television nearly 30 years later—and become, if anything, more popular than ever. In 1988, ESPN acquired the rights to the show, and the contests featuring legendary sluggers of the past—along with the occasional Wally Posts and Jim Lemons—found a whole new audience. The show had another successful run several years later on the Classic Sports Network. The entire 26-episode run was made available on DVD by MGM Home Entertainment in 2007.23

One of the people who reconnected with Home Run Derby when it returned to the airwaves was Mark Scott’s daughter, Mary Jane, who had been only eight years old when her father passed away in 1960. “One day in November of 1988, my mother called and told me that ESPN was broadcasting a show called Home Run Derby at 1:30 a.m.,” Mary Jane related. So early the next morning, Mary Jane turned on ESPN, “and there’s my dad, just like I remembered him. It was like an episode of The Twilight Zone. It was just mind-blowing.” Mary Jane subsequently got in touch with Larry Stewart, who had written a Los Angeles Times article about the return of the show, and Stewart invited her to a meeting of the Southern California Sports Broadcasters Association, which was honoring Home Run Derby.24

Mary Jane began attending SCSBA meetings on a regular basis, and a few years later, she and her mother attended a meeting of the organization whose theme was “Athletes to Actors.” Many of the guests at the “Athletes to Actors” meeting had been friends and colleagues of Mark Scott. Dorothy Scott was especially pleased to reconnect with Chuck Connors, who had been one of her husband’s closest friends during the 1950s.25

In the course of their conversation with Connors, Chuck introduced Mary Jane to Michael Dante—the actor and former minor league ballplayer who had befriended Mark Scott after working with him in Somebody Up There Likes Me. On this occasion, somebody down here liked Mary Jane—Michael Dante. The feeling was mutual. The two exchanged phone numbers, began dating, and a couple of years later, Mary Jane and her father’s old friend were married. A true Hollywood ending.26

“It was my dad who introduced me to Michael, through Chuck Connors,” Mary Jane Dante says. “My whole life changed through the return of Home Run Derby. It’s a miracle … my dad is alive and well. He is my guardian angel.”27

DON ZMINDA has worked for STATS LLC since 1992, first as the company’s Director of Publications and more recently as Director of Research. A member of SABR since 1979, he is the author or editor of more than a dozen books about baseball, including the SABR publication “Go-Go to Glory: the 1959 Chicago White Sox”. A native of Chicago, he has lived in Los Angeles since 2000.

Related links:

- Table 1: Click here to view Home Run Derby weekly results

- Table 2: Click here to view Home Run Derby player stats

Notes

1 Interview with Mary Jane and Michael Dante, 1 April 2010.

2 Interview with Mary Jane and Michael Dante, 1 April 2010.

3 http://www.imdb.com, filmography of Mark Scott.

4 Dante interview.

5 http://www.imdb.com, filmography of Lou Breslow.

6 Richard Hoffer, “Original Home Run Derby was a television show back in 1959,” SI.com, 30 June 2010.

7 Dante interview.

8 http://www.museum.tv, “Ziv Television Programs, Inc.”

9 http://www.museum.tv, “Ziv Television Programs, Inc.”

10 J.G. Taylor Spink, etc., Baseball Guide and Record Book 1961 (Charles C. Spink & Son, 1961), p. 151.

11 David Gough, “Home Run Derby: Looking back at a television sports legend,” The National Pastime No. 17, 1996, pp. 111–116.

12 Correspondence with Tom Saffell, March 2010.

13 http://www.imdb.com, filmography of Art Passarella.

14 “Art Passarella, Ex-Umpire, Later Acted in Films and TV,” obituary, New York Times, 16 October 1981.

15 STATS Pass (STATS LLC MLB database).

16 Gough, p.112.

17 “Home Run Derby, Volumes 1–3,” MGM Video, 2007.

18 “Home Run Derby, Volumes 1–3,” MGM Video, 2007.

19 Joe King, “Sluggers Swing for Heavy Sugar in TV Home Run Derby, The Sporting News, 2 March 1960.

20 Don Page, “Sandy Is Dandy on Baseball Commentary” (includes review of Home Run Derby), Los Angeles Times, 11 June 1960.

21 Gough, p.116.

22 Mark Scott obituary, The Sporting News, 20 July 1960.

23 Gough, 116.

24 Dante interview.

25 Dante interview.

26 Dante interview.

27 Dante interview.