Los Angeles’ Wrigley Field: “The Finest Edifice in the United States”

This article was written by Jim Gordon

This article was published in The National Pastime: Endless Seasons: Baseball in Southern California (2011)

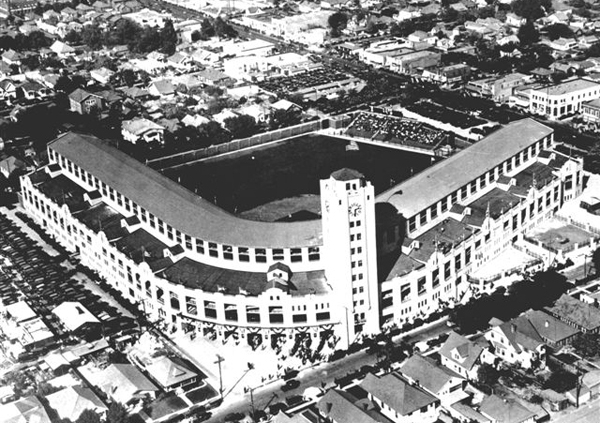

At Wrigley Field in Los Angeles, a 150-foot office tower housed 13-foot clocks on its four sides that could be seen from all parts of the city, making the ballpark the iconic symbol of baseball in Los Angeles for more than 35 years. (National Baseball Hall of Fame Library)

Chicago’s Wrigley Field, known worldwide, is considered a national treasure. Much less known is its Southern California counterpart. Los Angeles’ Wrigley Field was built in the exuberant Roaring Twenties and demolished at the end of the turbulent sixties. Both its birth and demise echo the spirit of the times. The ballpark lived through the Depression, World War II, the postwar baseball boom, the decline of minor league baseball and a brief renaissance as a major-league ballpark. The history of Wrigley is intermingled with that of the City of Los Angeles. It hosted the fiercest rivalry in minor league baseball between the Pacific Coast League (PCL) Angels and Hollywood Stars as well as other baseball, boxing, football, high school and a myriad of community events. And this being Los Angeles, the ballpark appears in many motion pictures.

The story begins in 1921, a few years after William K. Wrigley Jr. became principal owner Chicago Cubs, when he acquired the Los Angeles Angels of the PCL. After a dispute over parking at Washington Park, Wrigley decided to erect his own ballpark. Promising local fans a venue of major-league luxury, Wrigley commissioned architect Zachary Taylor Davis, who had designed Cubs Park (as Chicago’s Wrigley Field was then called) and Comiskey Park. Following Wrigley’s instructions to pattern the design after Cubs Park, Davis used iron and steel construction and designed a covered, double-decked grandstand from foul pole to foul pole, rarities in the minor leagues at that time. Built at a cost of $1,500,000,six times the cost of Cubs Park, it was dubbed “Wrigley’s Million Dollar Palace.” Seating about 18,500 in the grandstand and 2,000 in the bleachers, the ballpark was slightly larger than its Chicago counterpart. In later years the left-field wall was planted with ivy to further emulate that ballpark.

THE EARLY YEARS

On September 29, 1925, a crowd of 18,000 attended Wrigley Field’s dedication. A month later, The Sporting News published an effusive review of the new ballpark. Noting that there was not a sign to mar its beauty, and with an elevator to an observation platform with views from the mountains to the ocean, the newspaper found Wrigley Field to be in a class by itself architecturally, a “real monument to the national game.” Major league baseball owners, it argued, would not be able to boast of their parks when they saw this one and would have “to acknowledge that Wrigley has erected the finest baseball edifice in the United States.” Observing that the plasticity of today’s baseball had caused a cry for larger playing fields, the newspaper reported that Wrigley Field’s was among the largest. Home runs have been hit, it acknowledged, but those batters earned them. (It missed, however, the shortness of the power alleys.) Cubs Park may be excellent, The Sporting News concluded, “but the Angels have a better one.”1

The ballpark’s first full season was eventful. It began on January 15, 1926, with dedication of the clock tower by Commissioner Kennesaw Mountain Landis. On March 5, the Cubs became the first major-league team to play in Wrigley Field, losing the opener of a three-game series to the Angels. During the regular season, the Hollywood Stars, newly relocated from Salt Lake City, shared the ballpark with the Angels, an arrangement lasting through 1935. The silent comedy movie Babe Comes Home, starring Babe Ruth as Los Angeles Angels’ outfielder Babe Dugan and Anna Q. Nilsson as his love interest, became the first of many films shot at Wrigley Field. The Angels capped the ballpark’s inaugural season by winning the PCL pennant.

In early May 1930, Des Moines of the Western League had introduced lights and night baseball. The Sacramento Senators became the first PCL team to use lights on June 10. The first night game at Wrigley was played on July 22, with the Angels defeating Sacramento, 5–4, in 11 innings before 17,000 excited fans.2 Southern California had a vibrant winter league featuring major leaguers, PCL players, and usually a team from the Negro Leagues. For the 1930–31 season, the league split into an “official” Southern California Winter League and the Winter League. Playing at Wrigley Field, the Philadelphia Royal Giants participated in the Winter League, the first time since Commissioner Allen T. Burns’s ban of 1916 went into effect that a Negro League team was able to play ball in a PCL park.3

In 1932 the New York Giants became the first major-league team to use Wrigley as their spring training headquarters.4 On September 6, 1933, with the Angels on their way to the pennant, the all-time PCL attendance record of 24,695 was set for a night doubleheader.5 But by 1934, despite the Angels posting the best record in PCL history, the Depression was hitting Los Angeles hard and attendance was declining. The Angels and Stars drew less than 260,000 in 1934 compared to almost 400,000 the previous year. Hollywood had been losing money for several years, and in 1935 owner Bill Lane prepared to move the franchise to San Diego. The Stars went out in style, ending the season at Wrigley with a doubleheader against the San Francisco Missions. Actor Joe E. Brown amused the fans by umpiring in the second game and then pitching for the Missions with two out in the seventh inning to fan composer Harry Ruby while the rest of the team sat by the mound.6 The 1938 season saw a reincarnation of the Hollywood Stars when the Missions moved to Los Angeles and played in Wrigley for a year while awaiting the completion of their new ballpark, Gilmore Field, across town. Thus began a local rivalry enhanced by the competition between the west side and the central city/east side of Los Angeles.

From its beginnings, Wrigley Field had served as a community resource for high school athletics, semipro football, charitable events, and boxing. On January 15, 1939, the NFL champion New York Giants beat the All-American Stars in the first Pro Bowl before 20,000.7 Wrigley was used because the Coliseum Commission would not allow professional sports. The first of two Heavyweight Championship fights was held at Wrigley on April 17, 1939. Joe Louis knocked out Jack Roper before a crowd estimated between 23,000 and 30,000.8

After the 1941 season, major league baseball almost came to Wrigley when Don Barnes, St. Louis Browns president, orchestrated a covert deal to move the team to Los Angeles, with the Angels relocating to Long Beach as a Browns farm team. Barnes presented his proposal on December 9 at the Winter Meetings. Although other reasons were cited, the American League unanimously voted against it because of the Pearl Harbor attack two days earlier.9 The Los Angeles Times reported, “That the old gag about bringing major league baseball to Los Angeles was reborn at the American League meeting, but it lived a brief life.”10 The fans continued their support of minor league baseball, and attendance Wrigley Field would prove to be strong as World War II raged on. Because of the fear of a Japaese attack, the Army declared a restriction on night lighting along the Pacific Coast from Canada to Mexico and as far inland as 150 miles in August 1942.11 The Angels played their last night game on August 7, as fan stood and held lighted matches during the sounding of Taps and the singing of the national anthem.12

GLORY DAYS FOR THE PACIFIC COAST LEAGUE

With the war over, in 1946 crowds flocked to the ballpark. The Angels and San Francisco Seals battled for the pennant throughout 1947, finishing in a tie. Home attendance that season had reached 622,485, the all-time record, and nearly 23,000 fans jammed Wrigley for the one-game playoff, with thousands more turned away. With no score in the bottom of the eighth and the bases loaded, Angels outfielder Clarence Maddern hit the first pitch over the left-field wall.13 Fans have called this the greatest game in Wrigley history.

Near the end of that season, the Angels had televised their first game. However, as the major leagues began televising, interest in the minors declined and many leagues folded. To spur interest and increase broadcasting revenue, the Angels televised more games but attendance further declined. Despite such issues, local fans enjoyed memorable baseball moments, primarily between the Angels and Stars. On August 7, 1952, 23,497 fans attended a Stars-Angels game at Wrigley, the largest paid crowd for a PCL game in Los Angeles.14 Three days later, Hollywood swept a double header before 17,517 fans, who rioted after umpire Ed Runge called Stars catcher Jim Mangan safe at the plate in the 10th inning of the first game. Cushions were thrown and a fan charged onto the field. After the game, another fan attacked Runge and wrestled him to the ground. The second game was played with 35 extra policemen under the personal direction of Chief William Parker.15

The issue of how to bring major league baseball to Los Angeles persisted. No team would come without a major-league stadium, and nobody would create one without a team. Proposals were considered to upgrade Wrigley Field’s capacity to 40,000 or 50,000, but, these entailed condemnation of private housing and businesses and could not be accomplished quickly. Although he promoted upgrades, Philip K. Wrigley was not interested in covering the cost. He quietly hired Bill Veeck to sell the ballpark, but Veeck failed to find a buyer at a satisfactory price.16

But the local market for major league baseball was demonstrated during a 1955 spring training series between the New York Giants and Cleveland Indians meeting again after the 1954 World Series. In the first game, Willie Mays hit three home runs before 17,893. The next day 24,434 fans packed Wrigley to see Dusty Rhodes slug a pinch-hit homer and Willie Mays make an exceptional catch in deep center field.17

THE END OF AN ERA

In August 1955, after Walter O’Malley announced that the Dodgers would not play at Ebbets Field after 1957, Los Angeles city officials began working to attract the Dodgers. On February 21, 1957, the Los Angeles baseball world exploded when the Dodgers announced that they had bought Wrigley Field and the Angels for $3,000,000 plus their Fort Worth franchise.18 The Angels’ final season at Wrigley Field seemed anti-climatic as the anticipation of major-league baseball permeated the city. The Angels fared poorly; the fans’ primary interest was Steve Bilko’s pursuit of Tony Lazzeri’s home run record. The last PCL games were played in Wrigley, with San Diego sweeping a double header before 6,712. During the first game, the club received anonymous calls that there was a bomb in the dugout. The players were moved to the bullpens until the police checked the dugouts. However, the game was not delayed nor was the crowd informed.19

The Dodgers’ announcement that they would move to Los Angeles for the 1958 season came on October 8, 1957, one day after the Los Angeles City Council approved the transfer of Chavez Ravine to the Dodgers in exchange for Wrigley, with the idea of expanding the old park while the new one was built.20 Seating could be increased to 28,000 or 29,000 by enclosing the outfield with double-decked stands, the bleachers would be moved back towards Avalon Boulevard, and a 12-foot screen added in left. Then, the “soap opera” of where the Dodgers would play began, oscillating among Wrigley, the Coliseum, and the Rose Bowl. Expansion of Wrigley was reduced to 27,000, 26,000, and then to 24,000. Wrigley Field was found lacking; it had too few seats, too small a playing area, terrible parking, poor public transportation and it was situated in a declining neighborhood. Baseball Commissioner Ford Frick called it a “Cow Pasture.” He didn’t want to see Babe Ruth’s record of 60 home runs broken there.21 On January 17 the Dodgers and the Coliseum Commission agreed on a two-year contract.22 There would be no major league baseball at Wrigley Field—at least not yet.

Now owned by the city, and with the PCL Angels relocated to Spokane, Wrigley Field was used for various events. On August 18, 1958, Wrigley held its second heavyweight championship fight with Floyd Patterson retaining the title over Roy Harris before a crowd of 17,000.23 In 1959, the television show Home Run Derby began filming and aired for 26 weeks.24 The show was a nine-inning contest between two of the top sluggers of the era, providing the inspiration for the Home Run Derby now part of the All-Star Game festivities.

Then, in December 1960, the American League awarded an expansion franchise to Gene Autry christened the Los Angeles Angels. They were to play one year at Wrigley and four years at Dodger Stadium. The Los Angeles press criticized O’Malley for not sharing the Coliseum and for forcing an unfair lease upon the popular Autry. Some of their comments related to Wrigley. Sid Ziff predicted rough sledding with parking conditions that were prehistoric, rundown neighborhood, with $75,000 has-beens. Mel Durslag called Wrigley “an obsolete concrete shack.”25 Al Wolf said “Mob scenes at Wrigley Field, with the Coliseum empty, will arouse resentment among fans who believe O’Malley maneuvered the Angels into that small, parkingless park.”26 He added, “It is unfortunate that the club must open for business on short notice in an abandoned minor league park.” Nevertheless, the city undertook renovations at a cost of $275,000 to Wrigley: fresh paint inside and out, replacement of the sod and the seats, improved restrooms, refurbishment of the tower offices, and installation of radio and TV booths in an enlarged press box.

Wrigley Field hosted its first regular season major league game on April 27, 1961, after opening ceremonies featuring Commissioner Ford Frick and Ty Cobb.27 Sportswriters predicted the expansion team would be lucky to win 50 games, but the Angels won 70. General manager Fred Haney had played at Wrigley from 1929 through 1934 and managed the Hollywood Stars from 1949 to 1952. He was familiar with the park and structured the Angels accordingly. Thus the Angels were an excellent home team in their first season, winning 46 games for a .561 percentage.

The characteristics that made Wrigley a home-run paradise are important. The power alleys were a short 345 feet; the foul poles were a respectable 338.5 feet and 340 feet, and center field was a robust 412 feet. However, the fences were angled toward the infield more than 9 degrees. Thus the distance to the wall decreased as one moved away from the foul lines. The minimum distance to the wall was about 335 feet in left and right, making the power alleys, left and right, and left-center and right-center easy distances. Wrigley Field obliterated the minor league record for home runs with 248, a record that lasted until 1996 when 271 homers were hit at mile-high Coors Field. How good a hitters’ park was Wrigley? The home run park factor was 180. Almost twice as many homers were hit at Wrigley than at the average American League ballpark.

On October 1 the Angels’ Steve Bilko hit the last home run at Wrigley Field, a pinch-hit smash over the left-field wall with two out in the ninth inning.28 After the Angels departed for their four-year stint in the Coliseum, Wrigley Field staggered on for 7 1/2 years as a venue for local events. Its final highlight came on May 26, 1963, when a crowd of more than 35,000 attended the largest civil rights rally ever held in Los Angeles, where Martin Luther King Jr. said, “We want to be free whether we’re in Birmingham or Los Angeles.”29 August 1965 was a traumatic time in Los Angeles as civil unrest broke out and spread over the South Central area, culminating in what would be known as the “Watts Riots.” Many federal, state, city, and private commissions analyzed the causes of the unrest. One contributing factor was a lack of long-promised community services including parks, health and senior citizen facilities, and pressure built to have Wrigley Field better serve the community. In 1966, Wrigley was converted for soccer as arguments continued over final plans and funding. Finally, in March 1969, Wrigley Field was demolished to make way for the Gilbert W. Lindsay Community Center, which includes health facilities and a park with baseball fields still in use today. Wrigley Field had admirably served as a baseball and community sports center but its time had passed. Fond memories will always linger.

JAMES GORDON retired from TRW/Northrop Grumman after forty years as an aerospace and nuclear engineer to concentrate on baseball and being a grandfather. His joy is attending baseball games around the country and documenting aspects of Los Angeles baseball history. Having been born in Brooklyn, he is genetically and emotionally a Dodger fanatic, although he reached Los Angeles fifteen years before the team arrived.

Movies filmed at Wrigley Field, Los Angeles

| 1927 | Babe Comes Home |

| 1927 | The Bush Leaguer |

| 1929 | Fast Company |

| 1932 | Fireman Save My Child |

| 1933 | Elmer the Great |

| 1934 | Death on the Diamond |

| 1935 | Alibi Ike |

| 1949 | It Happens Every Spring |

| 1951 | Angels in the Outfield |

| 1951 | Meet Danny Wilson |

| 1951 | Rhubarb |

| 1953 | The Kid from Left Field |

| 1957 | Fear Strikes Out |

| 1958 | Damn Yankees |

Compiled by the SABR Ballparks Research Committee

Notes

1 The Sporting News, October 29, 1925, 3.

2 Los Angeles Times, July 23, 1930, 1.

3 William F. McNeil, The California Winter League – America’s First Integrated Professional League, McFarland & Company, 2008.

4 Los Angeles Times, February 18, 1932, A11.

5 Los Angeles Times, September 7, 1933, A9.

6 Los Angeles Times, September 23, 1935, A10.

7 Los Angeles Times, January 16, 1939, 21.

8 Los Angeles Times, April 18, 1939, 1.

9 Chicago Daily Tribune, December 10, 1941, 33.

10 Los Angeles Times, December 10, 1941, 10.

11 Los Angeles Times, August 5, 1942, 1.

12 Los Angeles Times, August 8, 1942, 11.

13 Los Angeles Times, September 30, 1947, 8.

14 Los Angeles Times, August 8, 1952, C1.

15 Los Angeles Times, August 11, 1952, C1.

16 Ned Cronin, Los Angeles Times, February 8, 1955, C3.

17 Los Angeles Times, March 21, 1955, C1.

18 Frank Finch, Los Angeles Times, February 22, 1957, 1

19 Frank Finch, Los Angeles Times, September 16, 1957, C1.

20 Frank Finch, Los Angeles Times, October 9, 1957, 1.

21 Los Angeles Times, January 12, 1958, C1.

22 Frank Finch, Los Angeles Times, January 18, 1958, 1.

23 Paul Zimmerman, Los Angeles Times, August 20, 1958, C1.

24 Joe King, The Sporting News, March 2, 1960, 8.

25 The Sporting News, December 14, 1960, 7.

26 Al Wolf, Los Angeles Times, December 19, 1960, C1.

27 Braven Dyer, Los Angeles Times, April 28, 1961, C1.

28 Braven Dyer, Los Angeles Times, October 2, 1961, C7.

29 Los Angeles Public Library Photo Database, #00032099, 1963.