Phillies Bonus Babies, 1953-57

This article was written by Sam Zygner

This article was published in The National Pastime: From Swampoodle to South Philly (Philadelphia, 2013)

Beginning in 1947 and ending in 1965, Major League Baseball instituted what became known as the “Bonus Rule.” Major league owners, many slow to react to changes in the landscape of the game, were coming to the realization that in order to build a winning team, it was necessary to build a strong farm system. The strategy centered on signing highly touted prospects with the hope that these players would develop and produce winning results.

The “Bonus Rule” was an initiative by Major League Baseball to restore some semblance of competitive balance and counteract teams like the St. Louis Cardinals, Brooklyn Dodgers, and New York Yankees who were stockpiling and burying players in their vast minor league systems. Under the rule, any team was allowed to sign a prospect—many of whom were just out of high school—to a bonus of $4,000 or more under the stipulation that they spend two years on a major league roster. Failure to follow the guidelines exposed the player to waivers, allowing him to be claimed by another team. Bonuses generally far exceeded the $4,000 minimum. Scouts vied for the services of these “Bonus Babies” by offering them lucrative contracts. The rule was temporarily rescinded in 1950 after several owners expressed dissatisfaction, but was re-instituted in December 1952 by a committee chaired by Branch Rickey, swinging open the door to what would become the rule’s most infamous years.1

During this period, one of baseball’s most prominent owners, Robert Carpenter Jr., although quite critical of the Bonus Rule, was quick to jump into the scrum by signing three of the most high profile talents available: Thomas Francis Qualters, Frederick William Van Dusen, and Mack Edwin Burk.2 Like most of these signees, they would find little gold at the end of their baseball rainbows. Nevertheless, each has a story to tell. Although major league dreams were fleeting, their experiences enriched their lives and forever changed them as individuals.

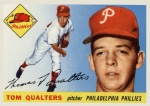

Tom Qualters: “They can beat ya, but they can’t eat ya”

There were two areas where young Tommy Qualters took like a duck to water: the outdoors and athletics. Growing up in the friendly hamlet of McKeesport in western Pennsylvania, practically a stone’s throw away from Forbes Field, he joyfully engaged in both endeavors. On the athletic side of the coin, young Qualters excelled in baseball, basketball, and football.

Although more focused on the gridiron than the baseball diamond, he had a change of heart after an encounter with a friend and member of the Pittsburgh Steelers, Ray Mathews. Though Qualters was only a sophomore in high school, Mathews engaged him in a conversation that changed the young lad’s life.

I had contacts from Division I schools, and things like that…So, I said, “how much money are you making Ray?” and he says $6,000. I went to bed that night thinking why would I go to college and get the heck kicked out of me for four years and if I’m any good I’ll go to the pros and get the heck kicked out of me. And so I made a sudden turn and I went to the high school football coach the next morning and I quit playing football and decide to concentrate on baseball.3

At 6’0″ and 175 pounds, the strapping teenager dominated his high school team, accruing a 27–5 record while leading his squad to the WPIAL finals his junior year and winning the championship his senior season.4 In addition, Qualters honed his talents during the summer, hurling for the East End Merchants in the Greater Pittsburgh League and barnstorming with former major leaguer Frank Gustine’s traveling club.5 Reportedly, 15 of the 16 major league’s team scouts were pursuing the baby-faced phenomenon who was commanding their attention with his crackling fastball. The Phillies made an offer of $50,000 (to be spread over an eight-year period), and upon graduating high school, Qualters was quick to sign on the dotted line.6 Some sources quote the actual amount to be $40,000. “The Phillies pursued me harder than anyone,” recalled Qualters. He added, “Come to find out, what I heard later on, I was the number one guy in the country.”7 Soon after signing he acquired the nickname “Money Bags” which followed him his entire baseball career.

The future appeared rosy for the 18-year-old, but his introduction to the major leagues would prove to be a rude awakening. To say his reception was cold would be an understatement. He remembered many of his teammates resenting his taking a roster spot from established veteran Jackie Mayo, which brought not only the ire of several players, but disdain from a clubhouse attendant nicknamed “Unk” who outfitted him in a too-small uniform for his first workout with the club. When Qualters approached the petulant attendant about receiving better-fitting togs, he was told in so many words, “If you don’t wanna wear the God damned thing, you can leave.”8

For two seasons, Qualters rode the bench and occasionally pitched batting practice. Admittedly, he knew he didn’t belong there, but he was caught between a rock and a hard place. “It was very frustrating. The players and manager (Steve O’Neill) were from the old school and didn’t accept me. You can imagine the resentment. …As a result I was off by myself most of the time.”9 However, a few of his teammates did their best to make the untried rookie feel at home, for which Qualters was grateful. “They treated me like one of the boys and were always giving me advice. I spent a lot of time with Jim Konstanty in the bullpen and he went out of his way to be nice, Robin Roberts, too.”10

Finally on September 13, 1953, during a lopsided contest against the St. Louis Cardinals, Qualters made his major league debut. With the Phillies trailing 11–1 in the bottom of the eighth inning, preparing to face Steve Bilko, the nervous rookie took his warm-up tosses. Bilko had already collected a pair of doubles and a single. It was an inauspicious beginning for Qualters when Bilko drove the ball deep over the fence for a home run. The misery continued as he allowed six runs on four hits, walked a batter, threw a wild pitch, and hit a batter, retiring only one man before being mercifully relieved by Konstanty.11

With the two-year obligation coming to an end, the Phillies decided to assign the 20-year-old to their Class-B affiliate in Reidsville, North Carolina. On June 14, 1955, he made his first start and tossed a five-hitter against High Point-Thomasville, earning a 6–3 win. His next start against Fayetteville did not go quite as well; he allowed 12 hits and seven walks, but earned his second straight win in the 11–7 victory.12 It wasn’t what Qualters had envisioned, but at least he had his chance to pitch every fourth day.

Under the watchful eye of manager and former major league chucker Charlie Gassaway, Qualters regained his sea legs. “It was hard getting back into competition. I had doubts about myself,” Qualters recounted.13 Although he had lost some zip on his fastball he developed a sinker that he thought would help him get back to the majors. He finished the season leading his team in games started (23) while compiling a respectable record (8–9, 4.90 ERA).14

The next year, Qualters impressed the Phillies brain trust enough to earn an assignment with Triple-A Miami of the International League. Under the tutelage of skipper Don Osborn, his role would change from starting rotation to swingman. His two years in Miami left him with some of the happiest memories of his career.

Qualters laughs when remembering his introduction to Miami and a lifelong friendship he made with a baseball icon.

So, I’ll tell you an interesting story about that… The club was run by Bill Veeck… So it was a longshot, in my mind, for me to make that ballclub. I had only played a half a year of class B ball… and so I go down there and I’m really working my tail off and there were many ex-major league players on the ballclub. Then they start cutting guys… Finally it comes—Opening Day—and I am there, I’m still there, and I’m absolutely amazed I made the ballclub.

Well, before the game started, a big crowd and everything, and all of the sudden here comes a helicopter in. It lands beside the mound and who comes out but Satchel Paige. And I thought, you old son-of-a-gun, you just took my job you…And it had turned out that they had cut another guy: it wasn’t me. So, in the aftermath of that, Satch and I became very, very close.15

To this day Qualters still works with kids, helping them with their pitching and hitting skills. Among the many fond memories he has of his baseball career, are sharing those seasons in Miami with the great Satchel Paige and enjoying fishing expeditions, shooting the breeze in the bullpen and playing “Skidoodle” with the baseball legend who he still recalls as a friend.

There are moments in life when something or someone changes your course forever. Qualters remembers some sage advice from Paige that he credits with saving his career.

We’re in a game and it’s very early in the season… But this was my first shot, here I am in AAA baseball, and it felt to me like I had made it to the majors. From the time I was a little kid I was never afraid of anything or anybody as long as I had a couple of rocks in my pocket which I carried all of the time, or a baseball in my hand. I had absolutely no fear of anything. And I come in the game and I get out there on the mound, most of these guys I’m playing against are ex-major league players… All of the sudden I’m on the mound and I’m taking my warm up tosses and I get the shakes. I mean I became petrified. I know I haven’t felt anything like that in my life. And you can’t bullshit another ballplayer, you know. Ballplayers can sense that, they can see it where nobody else can. Somehow or another I got them out. I threw the ball up there and they hit it at somebody or whatever. I got out of the inning. And I went home that night and I’m trying to figure how I can quit and go home. Not because of the fans or anything like that, just that I couldn’t stand the thought of players on the team thinking that I was a coward. I mean that was something that I had never gone through before. I was just totally lost.

So, we were in the bullpen the next night. Of course I’m sitting beside Satch and a couple of innings go along. Finally he comes and hits me on the leg and he said, “What’s the matter son?” I didn’t know what to do so I just told him the truth and I told him what happened. And he started laughing. He said, “I’m going to tell you son,” he said, “Those sons-of-a-bitches can beat ya, but they can’t eat ya.” Geez, they called down there and it’s me again. So I get back up there and I take my warm up tosses like right on the mound and I’m standing there and I start getting the shakes again, you know, and I just thought that’s it, the sons-a-bitches can beat me, but you can’t eat me and I got them out. From that day on I could hardly wait to get out there. But Satch, without question, saved my career.

With newfound confidence, Qualters put together two successful seasons in Miami in preparation for his return to Philadelphia. In 1956, he finished with a 5–5 record and an impressive 3.38 ERA working 80 innings. His second season was even better, again splitting time between the bullpen and starting rotation; he crafted an 11–12 record, started sixteen games, and collected three shutouts, improving his ERA to 3.29 while working 186 innings. He earned a late season call-up to the Phillies and appeared in 6 games, hurling 71⁄3 innings, with an ERA of 7.36.16

Qualters made the Phillies roster in 1958, but appeared in only one game before he was purchased by the Chicago White Sox and handed the role of reliever. Qualters proclaimed, “Al Lopez, without a doubt, was the greatest manager.”17 Although the Sox staff was well-stocked with quality relievers like Turk Lown, Bob Shaw, and Gerry Staley, Lopez found a spot for Qualters who appeared in 26 games (43 innings, 4.19 ERA).18

Buoyed by the confidence Lopez had in him, Qualters reported to White Sox spring training in 1959 with high hopes of breaking into the starting rotation; he was slated as a fifth starter. However, for the first time in his career, Qualters developed a sore arm, which he blamed on the pitching coach, Ray Berres, who tried to change his mechanics. “I’m trying to be pleasant and listen to him, but when I’d get out to the mound I would throw the way I always threw it, which was nothing wrong with it… my mechanics were fine, but he wanted me to throw like something out of a book.”19

Hoping that he would work through the injury, the White Sox assigned Qualters to Triple-A Indianapolis of the American Association. After pitching a few starts, he began to experience numbness in his fingers and his arm grew worse. Qualters recounted, “I was hurting all of the time and by the time I got to someone who knew a little bit about arms in those days…he gave me a shot of cortisone and he said don’t pitch for seven to 10 days.” He added, “Well I went back and told the manager [Walker Cooper] I wasn’t supposed to throw for seven to 10 days and a few days later I’m throwing again.”20

Qualters then began the nomad stage of his career, bouncing from Indianapolis to Houston and then San Diego in 1960 (7–9, 4.47 combined), and in 1961 to Indianapolis, Dallas Fort-Worth, and Williamsport (a combined record of 5–1, 4.90). By 1962, and pitching in constant pain, Qualters made a last stop in Dallas-Fort Worth (0–4, 10.80) before hanging up his cleats for good.21

Qualters made the transition to private life by working for the Atlantic Refinery Company managing service stations, before finding his true calling. After passing his civil service exam, he became a Conservation Officer and proudly served for 30 years before retiring. Tom and his wife raised five children and have 10 grandchildren.22 One grandson, Shawn Stiffler, is a pitching coach and recruiting coordinator for Virginia Commonwealth University.23

Fred Van Dusen: From bagging groceries to the big leagues

During the summers of 1954 and 1955, Fred Van Dusen received his fill of the elixir and drew attention from scouts from every major league team. The brash and boyishly handsome kid out of Bryant High School in Jackson Heights, New York, was exhibiting all the necessary tools: hitting for power and average, speed in the field and on the base paths, and a rocket arm. Representing the Astoria Cubs (Kiwanis) team from Queens, in the Hearst Sandlot Classic (HSC) held in the Polo Grounds, the 6’3″, 180-pound high school junior was turning heads. The HSC was one of premier tournaments in the country for young talent, featuring the likes of Whitey Ford, Billy Loes, Gene Conley, Al Kaline, and Moose Skowron, just to name a few. Hall of Famer Al Simmons, serving as a manager for the J-A All-Stars, cited the youngster from Queens PSAL as the top performer of the tournament.24

By graduation, the 18-year-old “phenom” was prepared to sign on the dotted line. The Van Dusen family was impressed by Phillies owner Robert Carpenter Jr. and they chose the Philadelphia Phillies and their generous bonus.25

Van Dusen would later refuse his bonus choosing instead to play in the minor leagues, but in 1955, like other Bonus Babies, Van Dusen was unfairly ostracized by most of his teammates.26 Rarely able to even appear in the batting cage, he waited impatiently to contribute. Finally, on September 11, 1955 at Milwaukee’s County Stadium, manager Mayo Smith signaled Van Dusen to step into the on-deck circle and prepare to hit. In the bottom of the ninth inning, with the Phils trailing the Braves 9–1, lanky right-hander Humberto Robinson stood on the mound ready to deliver the pitch. “I was numb, but I told myself to get up there and go down swinging,” said Van Dusen.27 On an 0–2 count Robinson delivered a bending curveball that nicked Van Dusen on the left knee, sending him to first base. The next batter, Stan Lopata, struck out, and Richie Ashburn popped out to right field to end the game. It would turn out to be Van Dusen’s only major league appearance, giving him the distinction to be the only major league player hit by a pitch while never making an appearance on the field.

Even though his major league career was short-lived, Van Dusen recounted with great pride, “Wow, you know, even to be on the field with those fellas was something.”28

After reporting to the Phillies spring training camp in 1956, Van Dusen was farmed out to the Wilson Tobs of the Class-B Carolina League.29 It was a struggle for the 18-year-old, and he blamed his own immaturity for his lack of success. “It happens to a lot of young players back in those days. I don’t think it happens today as much because they’re more mature.” He added, “But to come out of high school, go to the big leagues and sign, it was quite an emotional situation for a kid because you went from delivering groceries to being a big leaguer.”30

Van Dusen rebounded strongly in 1957 at Class-B High Point-Thomasville, finding his stroke and batting .310 in 119 games while bashing 25 home runs. He was named the Carolina League “Player of the Year” and appeared to be back on track.31 Brimming with confidence, Van Dusen was sure he would return to the Phillies in 1958, but instead was assigned to Triple-A Miami of the International League. As a 20-year-old brash youngster, he said with a smile, “They don’t know what they’re doing” and added “Chuck Essegian and I are the only .300 hitters on the roster. Don’t worry, though, I’ll be back. I’ll have such a great season; the Phils will have to get me back.”32

Van Dusen’s stay in Miami was brief; he appeared in 22 games while batting a paltry .167 with one home run and 5 RBIs. “I really stunk up the joint down there to be honest with you,” Van Dusen said.33 Not used to being platooned, he was especially frustrated and found himself demoted to Class-A Williamsport of the Eastern League for the rest of the season. Van Dusen returned to the Grays in 1959 and finished the season batting .272 in 106 games, with 14 homers and 65 RBIs. Most impressive was Van Dusen’s OBP of .437.34

Van Dusen stayed in the Phillies organization his whole career. He spent 1960 with Asheville of the Sally League and Indianapolis of the American Association and in 1961 with Chattanooga of the Southern Association.35 By then he could see the handwriting on the wall. “You go from prospect to suspect,” explained Van Dusen. He added, “You see younger guys pass you by and you know it’s time to pack it in.”36

Following his baseball career, Van Dusen found his niche in insurance and built his own lucrative business. He found love with his wife of 38 years and raised a happy family.

Now retired and living in Tennessee, Van Dusen received national attention when he threw out the first pitch on October 2, 2012, before a late season contest at Marlins Stadium. Van Dusen had been invited to this game to honor Adam Greenberg, who had become the second player to be hit by a pitch and never appear in the field. In his one-day comeback to the major leagues, Greenberg realized his dream of an official at-bat when he struck out on three pitches facing R.A. Dickey. Greenberg’s ceremonial at-bat returned Van Dusen to his solitary spot as the only player to be hit by a pitch and never appear in the field.37

Van Dusen summed up his life experience:

You know they say youth is wasted on the young. Because by the time you figure it out… I look at it as an experience. What I did learn was how to take defeat and get through it. I wish I could have learned that a little sooner, but that’s how the game is. Because you don’t always learn by doing it the hard way, but I learned by doing it the hard way.38

Mack Burk: “I thought I died and went to heaven”

Mack Burk has a soothing southern drawl that naturally draws people to him like a Texas barbeque draws a crowd. The tall, lanky youngster grew up in Nacogdoches, Texas, and found out early that he was a natural athlete. He started out playing softball on the hard dirt fields in the neighborhood before moving to baseball.

Burk caught the eye of several scouts while playing shortstop at Stephen Austin High School and competing against adults as a member of the Mechanics Uniform Supply amateur team which won the American Baseball Congress national championship in 1955.39 He was especially impressive during the tournament, batting a glossy .420 with a couple of home runs.40

After graduating high school, Burk at 6’4″, 175 pounds accepted a scholarship to the University of Texas in basketball. “The only reason I took the basketball scholarship was because they offered it to me early and I felt I could play baseball, too,” said Burk.41 Texas head coach Bibb Falk was ecstatic to have an athlete of such caliber and happily accepted Burk on the squad. However, fate stepped in and, after breaking his collarbone during his sophomore season at UT, Burk decided to focus on the diamond instead.42 On September 29, 1955, Burk sat down with his family and Hap Morse. After a bit of dickering he signed for a $45,000 bonus.43 The deal stipulated a $10,000 advance, the balance to be paid in three annual installments. One benefit was that Burk, a college junior, was able to purchase an 800-acre Texas ranch in partnership with his father Edwin.44

Burk reported to his first spring training in Clearwater, Florida, in 1956 unsure how much playing time he would receive. Upon arriving, Burk exclaimed, “I thought I died and went to heaven.”45 Surrounding him were players who, up to that point, he had only read about in the newspapers. “And I mean, here I am a 20-year-old kid, you know, and you got guys like Robin Roberts, and Curt Simmons, and Andy Seminick, and Stan Lopata, and Granny Hamner, and Willie ‘Puddin Head’ Jones, Del Ennis and Richie Ashburn; these were all guys I had been watching for years. Here I am riding the bus with them and training with them.”

Unlike many Bonus Babies, Burk had a very different experience with his baptism in the big leagues, as he fondly reminisced:

Robin Roberts was probably the nicest guy in the world. He kinda took me under his wing and told me not to do anything without consulting him because he didn’t want somebody taking advantage of me… he knew I was young. In fact all of them—Willie “Puddin Head” Jones and I were real good friends—the whole group, they accepted me and I didn’t have any problems at all.46

On May 25 he made his first major league appearance pinch-running for Andy Seminick in the eighth inning of a Phillies 8–5 loss to Pittsburgh. His first big league at-bat came on June 5 at Crosley Field in Cincinnati. Pinch-hitting for Curt Simmons in the fifth inning, Burk singled sharply to center field off Reds starter Joe Nuxhall and later scored on a Lopata sacrifice fly. Although it was a special moment for Burk, the Phils fell short in the run column, 9–4.47

He saw limited action his inaugural season and was used almost exclusively as a pinch-runner. His manager, Mayo Smith, used him several times, mostly running for second baseman Solly Hemus late in games. “I was kinda his designated pinch-runner whenever it would get late in the ball games,” said Burk. Although he received little playing time with the Phillies, Burk gained much experience working in the bullpen in addition to receiving advice from a hall-of-fame receiver. Burk recounted, “Of course I worked the bullpen. Benny Bengough was the bullpen coach. We were going north one year and playing the Yankees and Bill Dickey was still with the Yankees. And Benny took me over to him and the three of us sat down and talked for a long time about catching and everything.”48

The 1957 season found Burk wearing olive drab instead of Phillies flannel while serving on active duty in the reserves. He missed that entire season. The Phillies had planned for Burk to play in the Panama League for winter ball, but because of his late release he was unable to participate. With his Bonus Rule obligation fulfilled, the Phillies assigned Burk to Class-AA Tulsa (Oilers) in April 1958.49

After appearing in only eight games, and batting .182 in Tulsa, Burk was transferred to Williamsport Class-A of the Eastern League where he finished the year batting .236 in 94 games. That same season he returned to Philadelphia for his last major league at-bat and unceremoniously struck out. He closed his major league ledger with a .500 batting average.50

In 1959, Burk split time between Triple-A Buffalo of the International League and Williamsport again. Burk also served as Jimmie Coker’s backup for the pennant-winning Bisons, batting only .200 in 35 at-bats. Contemplating retirement from the game he loved during the offseason, Burk decided to give it one more go on his father’s prompting.

So one Sunday afternoon I’m sitting in my den with my mother and my dad. And my dad looked at me and said, “Son, you don’t have a job so you might as well go out there and get on that airplane and go to Florida to spring training.” I hadn’t even signed a contract. I go to Florida for spring training and give it one more shot. So I did and I ended up going to Asheville, North Carolina. They had some young pitchers there they wanted me to handle and so that was the last year that I played.51

Although it proved to be a fairly successful season behind the dish—with Burk hitting a solid .281 and driving in 46 runs in 114 games—he decided to hang up the tools of ignorance and move on. He was clear on his goals and stated, “I said I’m going to give it a few years and I’m not going to be a baseball bum and play in the minors for years…I just wanted to get established in life.” He added, “If I wasn’t going to make it, I wasn’t going to make it and I was going to quit.”52

After working many years in the electrical supply business, Burk retired in 1997 and now enjoys time off with his wife in the area of Houston, Texas. They enjoy traveling in their motor home and have been known to visit friends in Vero Beach, Florida now and again. He has no regrets from his baseball career and cherishes the friendships he made along the way.

SAM ZYGNER is chairperson for SABR’s South Florida Chapter. His article, “Racing the Dawn,” appeared in the “Baseball Research Journal” Fall 2012 edition. He has written sports- and travel-related articles for “La Prensa de Miami” from 2001–2005, and is writing a book, “The Forgotten Marlins: A Tribute to the 1956–1960 Original Miami Marlins.”

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank Tom Qualters, Fred Van Dusen, and Mack Burk for their contributions to this article. I am especially grateful to them for sharing their experiences and recollections of playing professional baseball and their personal lives, as well.

Notes

1. Steve Treder, “Cash in the Cradle: The Bonus Babies,” November 1, 2004, hardballtimes.com.

2. Joe Reichler, “Phillies Boss Raps Bonus Rule,” The Norwalk Hour, October 20, 1949, 28.

3. Tom Qualters, telephone interview, March 5, 2010.

4. Oscar Ruhl, “From the Ruhl Book,” The Sporting News, February 16, 1955, 14.

5. Ralph Katanik, “Tom Qualters: Phillies’ Bonus Baby,” Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, March 5, 1987, 7.

6. Les Biederman, “Bonus Baby Qualters Has No Regrets Over Bench-Warmer Role,” The Sporting News, February 17, 1954, 8.

7. Brent Kelley, Baseball’s Biggest Blunder: The Bonus Rule of 1953–1957 (Lanham, Maryland, Scarecrow Press, 1997) 26.

8. Ibid.

9. Tom Qualters, telephone interview, March 5, 2010.

10. Les Biederman, “Bonus Baby Qualters Has No Regrets Over Bench-Warmer Role,” The Sporting News, February 17, 1954, 8.

11. Baseball-reference.com.

12. “Tommy Qualters Making For Lost Time With Phillies,” The Sporting News, 38.

13. Tom Qualters, telephone interview, March 5, 2010.

14. Baseball-reference.com.

15. Tom Qualters, telephone interview, March 5, 2010.

16. Baseball-reference.com.

17. Tom Qualters, telephone interview, March 5, 2010.

18. Baseball-reference.com.

19. Tom Qualters, telephone interview, March 5, 2010.

20. Ibid.

21. Baseball-reference.com.

22. Tom Qualters, telephone interview, March 5.

23. VCUathletics.com.

24. Morrey Rokeach, “New York All-Stars Power-Packed in Sandlot Classic,” The Sporting News, August 11, 1954, 21.

25. The Sporting News, August 31, 1955, 4.

26. Art Morrow, “Phillies Line Up 44 Phenoms for Force-Feed Diet,” The Sporting News, February 8, 1956, 20.

27. William Weinbaum, “Van Dusen Feels Greenberg’s Pain,” ESPN.com, March 16, 2007.

28. Fred Van Dusen telephone interview, April 6, 2010.

29. Baseball-reference.com.

30. Fred Van Dusen telephone interview, April 6, 2010.

31. The Sporting News, November 6, 1957, 26.

32. George Metzger, “Rookie, Farmed by Phillies, Says, ‘Family Still Likes Me’,” The Sporting News, April 2, 1958, 33.

33. Fred Van Dusen telephone interview, April 6, 2010.

34. Baseball-reference.com.

35. Ibid.

36. Fred Van Dusen telephone interview, April 6, 2010.

37. Joe Frisaro, “Like Greenberg, Van Dusen’s career short-lived,” MLB.com, October 2, 2012.

38. Fred Van Dusen telephone interview, April 6, 2010.

39. Baseball-reference.com/bullpen/Mack.

40. Art Morrow, Burk, “Latest Flash Phil Find, Flashes Dash of Dickey Behind the Dish,” The Sporting News, March 7, 1956, 15.

41. Mack Burk telephone interview, October 19, 2012.

42. Art Morrow, Burk, “Latest Flash Phil Find, Flashes Dash of Dickey Behind the Dish,” The Sporting News, March 7, 1956, 15.

43. Baseball-reference.com/bullpen/Mack.

44. Art Morrow, Burk,”Latest Flash Phil Find, Flashes Dash of Dickey Behind the Dish,” The Sporting News, March 7, 1956, 15.

45. Mack Burk telephone interview, October 19, 2012.

46. Ibid.

47. Baseball-reference.com.

48. Mack Burk telephone interview, October 19, 2012.

49. Lee Schwartz, “Phillies’ Bonus Player 1.000 Hitter When Sent to Minors,” The Sporting News, April 30, 1958, 4.

50. Baseball-reference.com.

51. Mack Burk telephone interview, October 19, 2012.

52. Ibid.