The Show Girl and the Shortstop: The Strange Saga of Violet Popovich and Her Shooting of Cub Billy Jurges

This article was written by Jack Bales

This article was published in Fall 2016 Baseball Research Journal

This article was selected as the winner of the 2017 McFarland-SABR Baseball Research Award.

So, turn the key with me and enter Room 509 of the [Hotel Carlos], the most famous place in Chicago that you barely knew existed. — (Kankakee, Illinois) Daily Journal and (Ottawa, Illinois) Daily Times, April 10, 2010 1

The 1932 Chicago Cubs baseball season is probably best remembered for Babe Ruth’s gesture during the third game of the Cubs-Yankees World Series. Ruth may or may not have “called his shot,” but with her own shots earlier that summer, a young Chicago woman named Violet Popovich unknowingly set in motion the events that would indirectly lead to one of the most famous moments in baseball history.

Profiles of Cubs shortstop William Frederick “Billy” Jurges usually mention his wounding by jilted lover Popovich, while little is said about her background and career. Interviews, newspaper articles, and county and court archives have provided numerous heretofore unpublished biographical details. These facts also provoke questions about how Violet Popovich’s formative years may have contributed to her decision to burst into Jurges’s hotel room on July 6, 1932, and pull a gun from her purse.

The Shooting and Aftermath

Attractive and outgoing, Violet Popovich fell for Chicago Cubs shortstop Billy Jurges soon after she met him at a party in 1931. “Such a personality!” the 21-year-old brunette exclaimed a year later. “Such a man!…I love Bill Jurges for himself—and not for his place in the public eye or his popularity.”

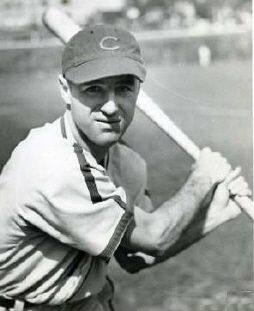

As for Jurges, age 24, his popularity and place in the public eye seemed assured during the Cubs’ 1932 season. The Brooklyn native had signed with the Cubs in 1929 and played minor-league ball until 1931, when manager Rogers Hornsby promoted him to the big leagues. Jurges competed in 88 games and finished his rookie year with a .201 batting average. After a healthy start in his second season in the majors, he was “playing brilliantly,” as reported in The New York Times, “and batting about .260.” The Sporting News considered his fielding “a defensive masterpiece, impelling no less an authority on infielding than his manager, Hornsby, to declare that Bill is the best shortstop in the game.”2

In Depression-era 1932, cuts in both team rosters and players’ salaries were the order of the day, so improving his game was likely uppermost in Jurges’s mind, not Violet Popovich. The former stage actress went to New York in May 1932 to pursue her acting career, but she succeeded in finding work only as a model for “confession” magazines. She wanted to pursue Billy as well, and when the Cubs traveled east on a road trip, she cheered him from the stands at Ebbets Field as Chicago took on Brooklyn. (She wrote her brother Michael that she even helped calm him down after he exchanged punches with Dodgers infielder Neal “Mickey” Finn on June 10.) She telephoned Jurges several times at his Brooklyn home, but as his father recalled a few weeks after the calls, “Bill talked to her but didn’t seem at all anxious about her. He never was a so-called ladies’ man. Since he was a little boy his only love has been baseball.”3

Jurges and Popovich quarreled sometime in mid-June, and she apparently stayed in New York while the Cubs continued their road trip. The team came home following a 4–1 loss to the St. Louis Cardinals on June 27. Popovich returned to Chicago on July 3 and took a room at the Hotel Carlos, her usual living quarters when she was in the city. Since the small residential hotel at 3834 Sheffield Avenue was just a couple of blocks north of Wrigley Field, during the summer months Jurges and some of his teammates also stayed there.

Ballplayers were at the Hotel Carlos on July 6, the day the pennant-chasing Cubs were set to open a three-game series against the Philadelphia Phillies. Popovich went to room 509 late that morning to talk to Jurges. While she, according to the Chicago Herald and Examiner, “was reproaching him for neglecting her,” she opened her purse and drew out a .25 caliber pistol. As the two struggled for the gun three shots were fired. One bullet entered Jurges’s right side, deflected off a rib, and came out his right shoulder. A second grazed the little finger of his left hand. A third hit Popovich’s left hand and went up her arm about six inches.4

The Chicago Daily Tribune reported that “the girl fled to her room while Jurges stumbled into the hall calling for help.” The Cubs team physician, Dr. John Davis, happened to be at the Hotel Carlos that morning and he treated both of them, who were taken to the Illinois Masonic Hospital. Jurges’s injuries were not as bad as they looked (his rib prevented the bullet from striking his liver, saving his life), and Davis said that he would be able to get back on the baseball field in two or three weeks. Popovich’s wound was superficial, and she was soon transported to the Bridewell Hospital, next to the Cook County Jail, in custody on a charge of assault with intent to kill.

When questioned by police, she told them that she was employed as a cashier in a store on the North Side of Chicago. In a search of her hotel room, officers found several empty liquor bottles and a letter addressed to her brother Michael, an employee of the Chicago Division Street YMCA. “To me life without Billy isn’t worth living,” she had written, “but why should I leave this earth alone? I’m going to take Billy with me.”

She quickly changed her story, insisting that she really had wanted just to shoot herself “to make Bill sorry” for breaking up with her. On July 7 she was interviewed from her cot in the Bridewell Hospital, where she told a Chicago Daily Tribune reporter that “I had been drinking before I wrote that note, and when I went to Billy’s room I only meant to kill myself. He knows that. I got a note from him today, after I wrote him one. He said he’d do anything he could to help me.”5

Billy did, too. He refused to press charges or sign a complaint, although Violet still faced arraignment in felony court on July 8. Her attorney explained to Judge John A. Sbarbaro that Popovich was under police guard in her hospital room and could not appear in court. Judge Sbarbaro responded that bond would be set at $7,500 and that he would continue the case until July 15. He added: “I understand that Bill Jurges has declined to prosecute the defendant. I want it understood that if he retains this attitude I shall issue a subpoena for his appearance as a witness.”

Jurges, recovering in his own hospital room, shook his head when he heard what Sbarbaro had decided. “Gee, I don’t see why the judge wants to be that way,” he said. “I certainly don’t want to prosecute Violet. I have no doubt that she shot me accidentally, she only wanted to kill herself and I tried to stop her. If I’m made to appear in court, that’s all I can say about the affair.”

Jurges may not have wanted to comment, but newspaper reporters had no such reticence concerning the “famous Carlos Hotel gunplay,” as the Chicago Evening American put it. Photographers barged into Popovich’s hospital room to take pictures of her recuperating in bed (she covered her face with her uninjured right arm as flashbulbs popped before her). Stories were plastered in newspapers around the country, often with glaring, tabloid-style headlines, such as “Crazed by Love Woman Tries to Kill Self” and “Jurges, Star Cub Shortstop, Wounded by Jilted Woman.”6

On July 15, 1932, 21-year-old Violet Popovich appeared in Chicago’s felony court with her two attorneys, Herbert G. Immenhausen (left) and James M. Burke (right). Note Popovich’s bandaged left arm. (COURTESY OF BILL HAGEMAN)

Reporters interviewed her at length while she was in the hospital. A Chicago Evening American journalist described how “the raven-tressed beauty tossed in her bed as she tore the curtain of secrecy from her troubled romance with Bill Jurges.” Popovich related that “I was unhappily married at 18—one of those puppy love affairs with a schoolboy. I never lived with him and we were divorced six months later.” In late 1929 or early 1930 she took dancing lessons at the Ned Wayburn studio in Chicago, which led her to the chorus of Earl Carroll Vanities. This series of stage musicals, directed by theatrical producer Earl Carroll between 1923 and 1940, featured dance revues, burlesque performances, comedy routines, and risqué sketches. In early 1931, probably after her Vanities engagement, Violet met Cubs outfielder Hazen Shirley “Kiki” Cuyler. She told the reporter that “he was very attentive,” but when she found out he was married, “I had nothing more to do with him.”

Then Billy Jurges entered her life. At the hospital Violet said that their relationship had been “perfect for many months,” but then “gossips began to cast aspersions on my character. It nearly killed me—for I could see that Bill’s ardor was waning.” She did not name any of the “gossips,” though she had singled out Kiki Cuyler in the letter found in her hotel room as one of the “few people” who “forgot that there might be anything fine and beautiful in our love for each other and dragged it in the mud.” Cuyler denied both going out with her and interfering with her romance, though he admitted that Jurges had asked him for advice concerning Popovich and that he had told the shortstop he was “too young to think of love.”7

Cuyler’s denial notwithstanding, Jurges recalled many years later that his teammate was “a big ladies’ man” and that Popovich had indeed dated Cuyler as well as other ballplayers. “I took the rap for it,” Jurges said, “but she had gone to Cuyler’s room first. …She had the key to his room but he wasn’t there. She wrote a note and put it on the mirror: ‘I’M GOING TO KILL YOU!’”8

Various other conflicting accounts muddy the details surrounding that day. For example, the Chicago Herald and Examiner wrote that shortly before noon on the sixth, Popovich “went to Jurges’ door on the fifth floor, pounding until he let her in.” On the other hand, Jurges said during a 1988 interview that she had called him from the hotel lobby at about 7:00AM, and he told her to “c’mon up.”

Did the original journalist get it wrong or did Jurges have difficulty (as one might imagine) recalling events of more than half a century ago? Researchers will probably never know exactly what occurred, but some particulars are well documented. Popovich was strong enough on July 9 to be transferred from the Bridewell Hospital to the adjoining Cook County Jail; later that day she was released on bail after a family friend, Lucius Barnett, posted her $7,500 bond. Jurges continued to convalesce at the Illinois Masonic Hospital. Dr. Davis allowed him to go to the ballpark on July 10, where he watched his teammates defeat the Boston Braves, 4–0.9

Jurges was also present in Judge Sbarbaro’s felony court on July 15, where the ballplayer was subpoenaed to appear as a witness against his former girlfriend. The Chicago Evening American noted that “baseball fans, girl romanticists and mere thrill-seekers” were on hand, as well as cameramen, from whom Jurges “screened his face with a handkerchief.” The Chicago Daily Tribune observed that once “a curious crowd had filled the courtroom,” Popovich, “a former chorus girl, made her entrance, wearing a white crêpe dress, trimmed in red, white hat and purse, and red shoes.” With her were her two attorneys, Herbert G. Immenhausen and James M. Burke.

Jurges had left the hospital and worked out with his teammates just two days earlier, and he was anxious to put his messy, public love life behind him so he could get on with baseball. As it turned out, Judge Sbarbaro was the ideal person to make the entire matter quietly disappear. Sbarbaro was not only a Cubs fan who did not want the team embarrassed but was also the consummate political “fixer.” (Incredibly, at the same time he served the public as a judge and attorney, he also ran a mortuary favored by Chicago’s mobsters and hid bootleg liquor in his garage.) Jurges stepped forward and told the judge that he did not want to press charges and that he expected no more trouble from his erstwhile girlfriend.

“Then the case is dismissed for want of prosecution,” Sbarbaro ruled, “and I hope no more Cubs get shot.” After the hearing, Popovich said that she would not try to contact Jurges. “I owe it to my self-respect to consider the entire matter a thing of the past,” she said. “If I happen to see Bill again it will be just impersonal.”10

Popovich may have considered the whole affair “a thing of the past,” but it continued to make headlines for both her and Jurges. Newspapers reported just a few days after the two of them appeared in court that the ballplayer was back in the hospital to have a bullet removed from his right side. According to an Associated Press story, it was not determined if he had originally been shot three times instead of twice or if the bullet that had struck his hand “lodged between the ribs and was overlooked.” The surgery proved to be just a minor setback for him, as he took the field in Pittsburgh for a July 22 game against the Pirates. In his absence, the usual third baseman, Woody English, had been playing shortstop, so Jurges took third. The Cubs lost, 3–1, but as the Tribune wrote, “Jurges bowed himself back into his profession by socking a single to center.”11

As for Popovich—no “shrinking” Violet—she wasted no time in capitalizing on her newfound notoriety. Jurges and the Cubs returned to Chicago after their brief road trip to discover through thousands of handbills distributed around Wrigley Field that Popovich was “seek[ing] solace in burlesque.” Although Jurges had refused to sign a complaint against her, she jumped at the chance to sign a contract—to headline at Chicago’s State-Congress Theatre as “The Girl Who Shot for Love.” Singing and dancing under her stage name, Violet Valli, she and her “Bare Cub Girls” made their debut on July 23 in the “Bare Cub Follies,” billed in the Chicago Daily Tribune as “A Screamingly Funny Burlesque Production.” Despite all the publicity, however, the show ran for only a few weeks. Her nephew, Mark Prescott, conjectured during a recent interview that her lack of success may have stemmed from her lack of talent. “She liked to sing,” Prescott said. “That is, she tried to sing.”12

A teenaged Violet Popovich poses on a city street. (COURTESY OF MARK PRESCOTT)

But Popovich had more important matters to worry about than her floundering stage career. On August 12 she once again appeared before Judge Sbarbaro; this time she sought his assistance in obtaining an arrest warrant for real estate broker Lucius Barnett, her former bail bondsman. She told Sbarbaro that while she was in the hospital, she had entrusted Barnett with twenty-five letters “of an affectionate nature” from Billy Jurges (they also purportedly included notes from Kiki Cuyler). She had asked Barnett to give the correspondence to her attorney, Herbert G. Immenhausen, as she was contemplating suing both ballplayers. She later changed her mind about the lawsuit, but Barnett had refused to return the letters, telling her that he wanted to publish them in booklet form as The Love Letters of a Shortstop and sell copies in ball parks around the country. He had promised her $5,000 up front and $20,000 later, but Popovich refused. “I wouldn’t let him do that,” she said. “I think too much of Bill.”

Sbarbaro suggested that her attorney seek an injunction against Barnett. The judge told reporters that “I’m a Cub fan myself” and “publication of letters that would hurt Jurges or the Cubs must be prevented.” Police officers discovered that Barnett had no intention of publishing the letters but instead wanted to blackmail Jurges and Cuyler by threatening each with a lawsuit. Barnett (“an alleged confidence man,” according to the Chicago Daily Tribune) was arrested at his home and charged with larceny and extortion. After he scuffled with officers and kicked one in the stomach, the charges of assault, disorderly conduct, and resisting a policeman were added to his list of offenses.13

On August 23, Judge Sbarbaro fined Barnett $100 on each of the three police charges. Sbarbaro dismissed the two remaining ones of larceny and extortion on September 8 when a sick Popovich failed to appear in court. By that time Barnett had returned all of Popovich’s letters to her, and Chicago’s newspapers quickly turned their attention to other matters. As Roberts Ehrgott summarized in his Cubs history, Mr. Wrigley’s Ball Club, “After two months of criminalities and sensationalism, the episode had ended with a whimper.”14

What had not ceased, however, was Violet’s ability to attract press coverage. She once again pursued her show business career, and in 1937 she was on stage as a “torch singer” in the Kitty Davis Cocktail Lounge in Chicago. On March 11 her friend Frederick B. Williams, a local businessman who worked in the office of his father’s hardware factory, drove to the lounge to pick her up. He became angry at having to wait for her to finish her act and change her clothes, and they started arguing. The fight escalated in his car after she demanded that he take her home, and he began speeding along the streets of Chicago, ignoring red lights and stop signs. “I insisted he let me out,” she told a policeman later that day, “and he said, ‘O.K., I’ll let you out.’ He opened the door and pushed me out.”

Popovich suffered minor scrapes and bruises, and the police advised her to file charges against Williams, with whom she said she had been “going” for four years. Hot tempers apparently cooled, for on October 13 the two applied for a marriage license. Their ardor, however, evidently cooled as well, for they never married.

Although Chicago’s newspapers covered Popovich’s automobile altercation, the reporters did not mention her past relationship with Billy Jurges. They would have had no reason to make the connection anyway. After Violet’s divorce she sometimes used her mother’s original surname (which Margaret went back to after her own divorce), and the articles focused on one Violet Heindl being pushed from the car, not Violet Popovich.15

Neither name appeared much in the papers after March 1937. Sportswriters would write occasional pieces on Jurges’s career mentioning the shooting, and “today in history” columns sometimes noted it. When a female fan shot Philadelphia Phillies ballplayer (and ex-Cub) Eddie Waitkus in his Chicago hotel room in 1949, Popovich and Jurges emerged as a footnote in some of the news stories.

Footnotes usually lead to additional information, but this was not the case with Violet Popovich. Who were her parents? What was her childhood like? Few people outside her family seemed to know much about her, but new research can now answer these and other pressing questions.16

The Troubled Past of Violet Popovich

Mirko Popovic was 25 years old when he stepped off a ship in New York City. Born in Krusevica, Austria, and an electrician by trade, Popovic had sailed from Hamburg, Germany, aboard the SS Kaiserin Auguste Victoria. The Hamburg-American liner had become lost for hours in the heavy fog around New York Harbor, but it finally managed to dock at the Port of New York on January 19, 1907.

Popovic soon settled in Chicago, and in 1910 he married Margaret Heindl, age 19, also from Austria. The couple had their first child, Viola, on March 21, 1911. Four other children would join their big sister: Drogiro (a girl born in 1912 but surviving only a few weeks), Michael (1913), Milos (1915), and Marco (1917).17

After a few years in the United States, Mirko Popovic Americanized his name to Michael “Mike” Popovich. Viola became Violet. Marco would soon answer to Mark, and both he and his brother Michael would change their last names to Prescott. Milos would change his name to Melvin Parker and then to Melvin Parker Popovich.18

The Popovich marriage was not a happy one. According to court documents, Margaret lived “in constant fear” of her husband, and he began beating her soon after Violet’s birth. “At that time my baby was only ten days old,” Margaret testified at a March 1920 divorce hearing. “After the baby was born he hit me in the face and over the body, and he gave me black and blue eyes.” Eight-year-old Violet took the stand during the hearing, but she was merely asked a few perfunctory questions, such as whether she attended Sunday school and if she knew the importance of telling the truth (she answered no and yes).19

Court papers also reveal that after the divorce, Michael Popovich, who worked as a night electrician in Chicago’s Insurance Exchange Building, provided little financial support for his family. Margaret was employed as a seamstress in a dressmaking establishment, but she was “unable to support the said children which she was given custody of, in a sanitary and wholesome manner.” The youngsters consequently lived at the Uhlich Children’s Home in Chicago, a private institution that cared for children without parents or whose parents could not provide for them. The Popovich boys were residents until 1932; in fact, in 1928 Michael told the superintendent that Uhlich’s was the only real home he had ever known.

Violet, however, hated foster care and wanted to live with her mother. She got her wish in 1922 after she deliberately set fire to one of the residence’s bathrooms. Violet’s mother evidently could not care for (or perhaps control) her daughter, for the girl wound up back in Uhlich’s. Violet still preferred her mother over a matron, and in 1926, shortly before her fifteenth birthday, she told Uhlich’s administrators that she would soon turn eighteen and asked for permission to leave. Her request was granted (apparently without verification of her true age), though four months later she may have regretted her decision. The Chicago Daily Tribune reported that the local police were called when the 15-year-old ran away from home after being “whipped for going to a movie with a boy and staying out late.”20

A young Violet Popovich, clad in overalls, spending time in the country with her equine companion. (COURTESY OF MARK PRESCOTT)

With such a childhood, there is little wonder that, as Violet told a reporter after she wounded Billy Jurges, “I was unhappily married at 18” and “divorced six months later.” Her subsequent pursuit of a theatrical career with Earl Carroll Vanities probably stemmed from her close friendship with an actress who was quite at home on the stage. Years later, this woman would be her confidante (and confederate) in the Hotel Carlos. The Chicago Evening American did not identify the person in its coverage of the shooting, but simply noted that as Violet “began pounding for admittance” to Jurges’s room, a “mysterious girl friend” with her “turned and fled.”

The Chicago Herald and Examiner was similarly vague when it wrote that the police were looking for Violet’s “mysterious blond companion.” The news-paper reported that Violet had received a telegram on July 6 that intimated Jurges had been out with other women. A resident of the hotel had overheard Violet exclaim to her friend, “If he denies this I’ll forgive him. Otherwise I’ll give him the works.” Notwithstanding all the frenzied media coverage about the shooting, newspapers could find very few details about the blond woman, though the Herald and Examiner observed that Violet’s mother knew her as “Betty.”21

Margaret certainly could have revealed more than just a first name, as the “mysterious blond companion” was none other than Violet’s stepsister, Betty Subject (original name Sopcak). Michael Popovich had married Anna Sopcak in 1922, when her daughter Betty was 26 and Violet 11. By then Betty had earned favorable reviews as an accomplished theater and film actress, particularly on the stage in the 1914 musical comedy September Morn. After she filed for divorce from her second husband in 1923 (she would be married four times), Betty learned that fame could be both fleeting and fickle. When she could not pay her rent in early 1924, one newspaper unsympathetically proclaimed, “September Morn Out of Luck.” Violet paid little attention to such headlines, however, for she looked up to her stepsister as a true “big sister.” When Violet went to New York in May 1932 to seek work in the theater, Betty accompanied her.22

The 1932 Cubs

The Cubs were leading the National League in early June, but after their loss to Pittsburgh on July 22—the day Billy Jurges rejoined his teammates—they found themselves 3½ games behind the hard-charging Pirates. Whispered comments within the Cubs organization centered not on the ballplayers’ skills but on the obvious animosity between club president William Veeck and manager Rogers Hornsby. Veeck believed that the team was easily good enough to win the National League pennant, and he was growing weary of Hornsby’s constant carping about the men and their perceived shortcomings. The ballplayers themselves had little use for their brusque and no-nonsense manager, who publicly (and frequently) pointed out their mistakes and berated them for not measuring up to his standards. After the Brooklyn Dodgers defeated the Cubs and their ace pitcher, Lon Warneke, on August 2, Veeck fired Hornsby and appointed as manager the popular first baseman, Charlie “Jolly Cholly” Grimm.

Just three days later, Veeck purchased Mark Koenig from the Pacific Coast League’s Mission Reds to help out in the infield. Koenig had joined the Yankees in 1925, and two years later he batted .285 for the famed “Murderers’ Row” team. In 1930, however, his batting average was only .230 in 21 games and on May 30 he was traded to the Detroit Tigers. Unfortunately for the former Yankee, the Tigers would soon be delighted with Billy Rogell’s performance as shortstop, and by 1932, Koenig found himself in the Pacific Coast League. He batted .335 in 89 games for the Mission Reds.

One could make a case that the Cubs hired Koenig as a roster replacement for Hornsby, who had occasionally inserted himself into the lineup. But sportswriters observed that Veeck had been concerned about Jurges’s recovery following the shooting and that the Cubs president mentioned he wanted another shortstop as a backup. Scout Jack Doyle recommended Koenig, who justified Doyle’s faith in him on August 14. As Arch Ward wrote in his Chicago Daily Tribune column, Koenig “hit the first ball thrown to him in the National League for a single, and he has been busting ’em ever since.”23

The Cubs were also “busting ’em,” thanks to new manager Charlie Grimm. “Jolly Cholly” was living up to his nickname, and the team flourished under his buoyant personality and easygoing, even-tempered leadership style. Both Jurges and Koenig played shortstop, though Koenig was making the headlines—and the heads turn. On August 20 in a game against the Philadelphia Phillies he became “Chicago’s baseball hero of heroes,” as sportswriter Edward Burns phrased it in the Tribune. With two men on base and two out in the ninth inning and the Cubs down 5–3, Koenig drove Ray Benge’s first pitch “high into the right field stands for the wildest of the wild finishes that are becoming habitual with the Cubs.”

That wild day marked the first victory in a 14-game winning streak that gave the Cubs a solid grip on first place. They never let up and clinched the National League pennant on September 20, finishing the season with a record of 90–64, four games in front of Pittsburgh. Koenig proved to be a potent factor in Chicago’s drive to the flag, for in his 33 games he batted .353. “The ball started bouncing for us the first day Mark put on a Cub uniform,” Charlie Grimm recalled years later. “He did everything right and turned out to be a leader in the field.”24

Some of Koenig’s teammates, however, focused on the length of his tenure rather than his accomplishments during it. The Cubs met to vote on the division of the World Series playoff bonus, as a player’s full share required unanimous approval. Billy Jurges and second baseman Billy Herman insisted that Koenig deserved only a half-share, not a full one. “We figured he wasn’t entitled to it,” Jurges remembered. “He did win the pennant for us, but he didn’t play that many ball games.”

The New York Yankees, Koenig’s former team and Chicago’s World Series opponents, figured differently. When the newspapers announced the breakdown of the postseason players’ pool, the Yankees (and Babe Ruth in particular) berated the Cubs as cheapskates and penny-pinchers. “Sure, I’m on ’em,” Ruth scornfully admitted in a Chicago Daily Tribune article. “I hope we beat ’em four straight. They gave Koenig…a sour deal in [his] player cut. They’re chiselers and I tell ’em so.”

Sportswriter Shirley Povich succinctly appraised the championship showdown when he wrote that “the Cubs’ stinginess fired the Yankees to new heights.” The Cubs lost the first two games in New York, 12–6 and 5–2, and on October 1 the World Series shifted to Chicago. Both teams had been shouting insults at each other since the Series started, and as Billy Herman recalled, “Once all that yelling starts back and forth it’s hard to stop it, and of course, the longer it goes on, the nastier it gets. What were jokes in the first game became personal insults by the third game.”25

The score was tied in the fifth inning of the third game, 4–4, when Babe Ruth stepped to the plate and faced pitcher Charlie Root. With the count two balls and two strikes, Ruth gestured with his right hand. Did the left-handed slugger look at the Cubs dugout (or Root) and hold up two fingers to indicate that that was only two strikes and he had one left? Did he point to center field as if to signal or “call” a home run? Countless barrels of ink have been spilled in published debates and discussions over his intention, but what happened next is unarguable: Ruth smashed Root’s next pitch over the center-field fence. Lou Gehrig followed Ruth to the plate and also hit a home run, leaving the Chicago team thoroughly demoralized. “The Yankees just had too much power for us,” third baseman Woody English sighed years later. “It was discouraging.”

Violet Popovich married when she was 18 years old. She was about that age when she sat in a doorway and had her picture taken. (COURTESY OF MARK PRESCOTT)

It was even more discouraging for the Cubs when they lost the game by the score of 7–5, later losing the Fall Classic in four straight games (as Ruth had hoped they would). Mark Koenig, who batted 1-for-4 in the Series (.250), was not surprised at the outcome. “I never fit in with the Cubs players,” he said. “They only voted me a half-share of the World Series.… I knew damned well we couldn’t beat [the Yankees].” Koenig played one more year for the Cubs before he was traded to the Philadelphia Phillies in November 1933.

Jurges performed well at the plate in the 1932 postseason, batting 4-for-11 (.364). The Tribune reported in December that “Bullet Bill Jurges, though he had many things to distract him,” led the National League shortstops with his .964 fielding percentage in 108 games (shortstop Dick Bartell of the Phillies played in 154 games and finished the year with a .963 percentage).26

Even though “Bullet Bill” remarked after he was shot that he had no intention of getting married and that “I guess I’ll remain a bachelor all my life,” he soon changed his mind. In the morning of June 28, 1933, he married Mary Huyette in Reading, Pennsylvania. Later on that day he celebrated his wedding with six hits in a Cubs-Phillies doubleheader (Chicago won the two games, 9–5 and 8–3).

Jurges was traded to the New York Giants in December 1938. He returned to Chicago as a utility player in 1946, where he wound up his last two seasons in the major leagues. Jurges then coached, served as an infield instructor, managed in the minor leagues, and in 1956 helped coach for the Washington Nationals (popularly known as the Senators). He was hired as manager of the Boston Red Sox in July 1959, replacing Mike “Pinky” Higgins. Although Jurges finished the 1959 season with a 44–36 record (.550), by mid-June of 1960 the slumping Red Sox were in last place, and he was fired and Higgins brought back. Jurges told an interviewer while reflecting on his brief time in Boston that “it is very important for managers to get a ball club with players on the way up. On that club, most of them were on the way down.”

Jurges continued to work in baseball as both a scout and an instructor, eventually retiring in Largo, Florida. He was diagnosed with cancer in 1991, and he died on March 3, 1997, at the age of 88. He and his wife had one daughter, Suzanne Jurges Price. When Price was asked a few years ago if she knew that Violet Popovich had shot her father in 1932, she said she was familiar with the incident but that when she was growing up “it was never mentioned in our house.”27

The Later Years of Violet Popovich

In the early 1930s Margaret Heindl moved to Los Angeles, California, and by 1940 her daughter had joined her. Violet still had show business aspirations, although the 1940 census notes that none of her income the previous year had been earned through professional singing. In 1947 Violet married Charley Retzlaff, a former heavyweight prize fighter from North Dakota who had fought out of Duluth, Minnesota. (How and where she met him is unknown.) Retzlaff’s first professional fight had been in 1929, and he lived up to his nickname, “The Duluth Dynamiter,” until January 17, 1936, when a young Joe Louis knocked him out in less than two minutes. Retzlaff retired in 1940 and returned to his family farm in the small North Dakota community of Leonard. After his marriage he expected his wife to enjoy rural life as much as he did, but according to her nephew, Mark Prescott, Violet stayed only about a week at the farm before she moved back to Los Angeles.

She and her husband did not get divorced, however, and Prescott mentioned during an interview that the two stayed in touch and remained on friendly terms. Prescott added that his aunt was certainly not at a loss for male companions, as she was a five-foot, nine-inch “stunning beauty” with an olive complexion and gray eyes. She went out with quite a few baseball players, including future Cubs manager Leo Durocher and future White Sox manager Al Lopez. Prescott particularly remembered going to a 1959 White Sox game with his aunt when he was nine years old. Lopez came into the stands to chat with them, bringing a baseball which he autographed for the boy.28

Violet lived in the Studio City neighborhood of Los Angeles and worked in the color department of a film studio. She was not well off financially, and following her retirement she had a couple live with her to help with expenses. When she could not afford to pay the property taxes on her house, she agreed to sell it to the man and woman on the condition that they allow her to stay there. Violet had failed to consult a lawyer to protect her legal rights, and after the couple took possession of the house they changed the locks, effectively evicting her. She spent her final years in a nursing home, where she would often talk about her past as a show girl. She died at age 88 on February 25, 2000, and was buried in Los Angeles’s Forest Lawn Memorial Park–Hollywood Hills. She had outlived her parents; her father had died in Chicago in 1945 and her mother twelve years later in Los Angeles.

Violet (about age 40), stands behind her mother, Margaret Heindl. (COURTESY OF MARK PRESCOTT)

One question in particular can now be answered: Had Violet intended to kill Billy Jurges when she entered his room at the Hotel Carlos? The letter that she had left in her own hotel room clearly indicates that murder had been on her mind, but after her arrest she declared that she had only meant to use the gun on herself. Mark Prescott said that years later she confided to his mother that she had, indeed, gone to room 509 with the express purpose of shooting the ballplayer. As she told her sister-in-law, “I was very angry and I wanted to kill him.”29

Violet’s turbulent upbringing and abusive father do not excuse her behavior, but they may explain what she longed for from Jurges: intimacy and commitment. Chicago Cubs historian Ed Hartig believes that “she was desperate for attention and affection—certainly not getting that from her family life, especially from her father and a failed marriage. I think she felt that she finally would find it with Billy Jurges—though if it hadn’t been Jurges, she likely would have latched onto almost any ballplayer.”

When Violet recklessly pulled the trigger in the Hotel Carlos, her bullets not only struck Jurges but had a domino effect on the Cubs, Mark Koenig, the 1932 pennant race, the division of the World Series money, and Babe Ruth’s arguable “called shot.” As Hartig contends in an article for Vine Line, the Chicago Cubs magazine, “The shooting of Jurges opened the door for Koenig to become a Cub and baseball legend.”

The shooting made Violet something of a legend as well. It is possible that years later she and Ruth Ann Steinhagen (who had wounded Eddie Waitkus) inspired Bernard Malamud to include a paragraph in his 1952 novel, The Natural, in which a woman shoots ballplayer Roy Hobbs. The Natural and that scene continue to live on today, thanks to the fan-favorite 1984 motion picture starring Robert Redford as Hobbs. And Violet Popovich will remain a part of baseball, too, inextricably linked to the 1932 season and one of the most unfortunate and unusual episodes in the sport’s history.30

JACK BALES has been the Reference and Humanities Librarian at the University of Mary Washington in Fredericksburg, Virginia, for more than 35 years. His Chicago Cubs articles include a biography of Bill Veeck Sr. in the Fall 2013 issue of The Baseball Research Journal.

Acknowledgements

The author gratefully acknowledges the assistance of his current and former colleagues at the university, including Rosemary Arneson, Carla Bailey, Peter Catlin, Suzanne Chase, Bill Crawley, Renee Davis, Tina Faulconer, Claudine Ferrell, Christie Glancy, Shannon Hauser, Elizabeth Heitsch, Pauline Jenkins, Andrea Meckley, John Morello, Tim Newman, Carolyn Parsons, Katherine Perdue, Beth Perkins, Jessica Reingold, Tom Sheridan, and Erin Wysong. He also appreciates the assistance and support of Art Ahrens, David Bales, Dick Bales, Michael Bales, Roberts Ehrgott, Bill Hageman, Ed Hartig, Ellen Keith, Ray Kush, Lesley Martin, Gary Mitchem, Mark Prescott, Christina A. Reynen, Trey Strecker, Tim Wiles, Dave Wischnowsky, and Tom Wolf. Bales presented his research on Violet Popovich in March 2016 at the NINE Spring Training Conference in Tempe, Arizona.

Notes

1. Dave Wischnowsky, “Cubs Lore? It’s Only ‘Natural’ in Room 509,” The Wisch List, accessed June 4, 2016, http://wischlist.com/2010/04/cubs-lore-its-only-natural-in-room-509/. This article refers to the hotel as the “Sheffield House Hotel,” which the Hotel Carlos was renamed in the mid-twentieth century.

2. Popovich meeting Jurges at a party is in Virginia Gardner, “Jurges’ Girl Friend Blames Shooting on ‘Too Much Gin,’” Chicago Daily Tribune, July 8, 1932, 3. “Such a personality!” quotation, meeting Jurges in 1931, and Popovich’s personal characteristics are in “Cub Star Not to Prosecute Divorcee,” Chicago Evening American, July 7, 1932. Jurges’s game statistics are in http://www.retrosheet.org/. “Playing brilliantly” quotation is from “Bill Jurges Wounded by Girl He Rejected,” The New York Times, July 7, 1932, 18. “A defensive masterpiece” quotation is from “William Frederic[k] Jurges,” The Sporting News, May 26, 1932, 1. Jurges’s career is in Paul Geisler Jr., “Billy Jurges,” SABR Baseball Biography Project, Society for American Baseball Research, accessed May 20, 2016, http://sabr.org/bioproj/person/aada6293. See also “Bill Jurges, Nobody in the Minors, Big League Success,” Chicago Daily Tribune, June 4, 1931, 27.

3. Salary and roster cuts are in Associated Press, “Salary Lists of Major Leagues to Be Cut $1,000,000 This Year,” The New York Times, January 13, 1932, 28; Charles C. Alexander, Breaking the Slump: Baseball in the Depression Era (New York: Columbia University Press, 2002), 36–60. Popovich resuming her career and watching Jurges play is in “Note Reveals Girl Planned to Kill Jurges,” Chicago Herald and Examiner, July 7, 1932 (two different but identically titled articles from two editions of the newspaper, one from the Last Metropolitan edition, pages 1 and 3, and the other from an unknown edition, pages 1 and 5). The phrase “confession story magazines” is in Gardner, “Jurges’ Girl Friend Blames Shooting.” Photographs of Violet as a model are in the Chicago Evening American, July 7, 1932. The Jurges and Finn fight is in Roscoe McGowen, “12,000 See Robins Topple Cubs, 4 to 3,” The New York Times, June 11, 1932, 11. “Bill talked to her” quotation is from Margery Rex, “Jurges’ Father Says Bill Did Not Love Girl,” Chicago Evening American, July 7, 1932. Conversations are also in “Bill Jurges Wounded by Girl He Rejected.”

4. Jurges and Popovich quarreling and the Hotel Carlos are in “Letter Solves the Shooting of Bill Jurges,” Chicago Daily Tribune, July 7, 1932, 1; “Crazed by Love Woman Tries to Kill Self,” Chicago Evening American, July 6, 1932 (notes that Popovich occupied room 111 in the Hotel Carlos). Game logs are in http://www.retrosheet.org/. Cubs and Popovich returning to Chicago is in “Cub Star Not to Prosecute Divorcee.” Popovich living in the hotel and the “was reproaching him” quotation are in “Note Reveals Girl Planned to Kill Jurges,” 1, 5 (notes the address of Popovich’s mother, Mrs. Margaret Heindl, as 743 Belden Avenue in Chicago). Gun shots are in “Bill Jurges Wounded by Girl He Rejected.”

5. “The girl fled to her room” and “to me life without Billy” quotations, John Davis, and liquor bottles are in “Letter Solves the Shooting of Bill Jurges.” Popovich in custody at Bridewell Hospital is in “Charge Violet with Attempt to Kill Jurges,” Chicago Herald and Examiner, July 8, 1932, 7. Popovich’s job as cashier is in “Jurges, Cubs’ Shortstop, Is Shot by Girl,” Brooklyn (New York) Daily Eagle, July 6, 1932, 1. One newspaper said she was “a cashier in a Chicago cigar stand.” See “Local Ball Star Victim of Attack in Chicago Hotel,” (Forest Parkway, New York) Leader-Observer, July 7, 1932, 1. “To make Bill sorry” and “I had been drinking” quotations are from Gardner, “Jurges’ Girl Friend Blames Shooting.”

6. Jurges refusing to press charges and Popovich facing arraignment are in “Charge Violet with Attempt to Kill Jurges.” Sbarbaro, Jurges, and “Famous Carlos Hotel gunplay” quotations are in “Jurges Must Accuse Girl, Says Court,” Chicago Evening American, July 8, 1932. An ACME Newspictures wirephoto from the author’s collection, dated July 6, 1932, has this caption: “Miss Popovich is shown above a few hours after the shooting, hiding from photographers.” Articles are “Crazed by Love Woman Tries to Kill Self,” Chicago Evening American, July 6, 1932; “Jurges, Star Cub Shortstop, Wounded by Jilted Woman,” Milwaukee Sentinel, July 7, 1932, 1.

7. Chicago Evening American interview, quotations, and biographical details are from “Cub Star Not to Prosecute Divorcee.” Similar details are in “Charge Violet with Attempt to Kill Jurges.” For opening of Ned Wayburn’s dancing studio see “Ned Wayburn, Noted Follies Producer, Opens Dancing Studio in Chicago,” Chicago Daily Tribune, November 10, 1929, sec. E, 7. In Gardner, “Jurges’ Girl Friend Blames Shooting,” the author states that Popovich joined the chorus of Vanities in 1928, which is contrary to details in the Chicago Evening American interview that imply 1929 or 1930. Information on Earl Carroll Vanities is in Thomas Hischak, The Oxford Companion to the American Musical: Theatre, Film, and Television (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2008), 219. Violet’s stint with Vanities was in Chicago, as per “Note Reveals Girl Planned to Kill Jurges,” Last Metropolitan edition, 3. “Few people” and “forgot that there” quotations are from “Letter Solves the Shooting of Bill Jurges.” Cuyler’s denial of dating Popovich is in “Crazed by Love Woman Tries to Kill Self.” The “too young to think” quotation is from “Jurges Refuses to Act Against Girl Assailant,” Chicago Evening Post, July 7, 1932, 4.

8. “A big ladies’ man” quotation and Popovich dating ballplayers are in Jerome Holtzman and George Vass, Baseball, Chicago Style: A Tale of Two Teams, One City, new exp. ed. (Los Angeles: Bonus Books, 2005), 54. On the evening of July 5, Violet “was heard exclaiming loudly in her room: ‘I’m going to get Bill, and maybe “Kiki,” too,’” as per “Note Reveals Girl Planned to Kill Jurges,” Last Metropolitan edition, 3. Bill Veeck wrote in his memoir that a “very jealous” Popovich came to the Hotel Carlos looking for her married lover and found him in Jurges’s room. Jurges stepped between them and was accidentally shot in the hand. “Billy, being single, kept the intended victim’s name out of it, leaving everybody to believe that he had got shot on his own merits.” See Bill Veeck, with Ed Lynn, The Hustler’s Handbook (New York: G. P. Putnam’s Sons, 1965), 164. See also Roberts Ehrgott, Mr. Wrigley’s Ball Club: Chicago and the Cubs During the Jazz Age (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2013), 286–88; Charles DeMotte, “Baseball Heroes and Femme Fatales,” in The Cooperstown Symposium on Baseball and American Culture, 2002, ed. William M. Simons (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland, 2003), 315–18.

9. “Went to Jurges’ door” quotation is from “Note Reveals Girl Planned to Kill Jurges,” 5. “C’mon up” quotation is from Holtzman and Vass, Baseball, Chicago Style, 53. Popovich leaving the hospital for the jail and posting bond is in “Girl Who Shot Jurges Is Freed on $5,000 [sic] Bond,” Chicago Daily Tribune, July 10, 1932, 3; “Girl Who Shot Jurges Freed in Bail,” The New York Times, July 10, 1932, 8. Jurges watching the ball game is in “Bill Jurges Out of Hospital; Sees Cubs Beat Braves,” Chicago Daily Tribune, July 11, 1932, 19. Game logs are in http://www.retrosheet.org/.

10. “Baseball Fans, girl romanticists” quotation is from “Jurges’ Plea Frees Girl in Shooting,” Chicago Evening American, July 15, 1932. “A curious crowd” and Sbarbaro’s and Popovich’s quotations are from “Girl Who Shot Cubs’ Player Goes Free,” Chicago Daily Tribune, July 16, 1932, 3. Jurges working out is in “Billy Jurges Back in Uniform,” Chicago Herald and Examiner, July 14, 1932, 11. Sbarbaro as a Cubs fan wanting to protect the team is in “Girl Who Shot Cub Ball Player Asks Arrest of Agent,” Chicago Evening Post, August 12, 1932, 1. Sbarbaro’s political life is in “Three Bombed; One a Judge,” Chicago Daily Tribune, February 18, 1928, 1; Laurence Bergreen, Capone: The Man and the Era (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1994), 136, 145, 277–78; Jonathan Eig, Get Capone: The Secret Plot That Captured America’s Most Wanted Gangster (New York: Simon and Schuster, 2010), 48.

11. “Lodged between the ribs” quotation is from “Another Bullet Found in Jurges,” Brooklyn (New York) Daily Eagle, July 19, 1932, 8. Both John Davis, the Cubs’ physician, and Jurges said it was a third bullet. See “Jurges Shelved Longer; Remove Third Bullet,” Chicago Daily Tribune, July 19, 1932, 17; Holtzman and Vass, Baseball, Chicago Style, 53–54. “Jurges bowed himself” quotation is from Edward Burns, “Cubs Lose, 3–1; Trail Pirates by 3½ Games,” Chicago Daily Tribune, July 23, 1932, 9. Jurges is referred to as “the celebrated revolver target” in “Jurges on 3d Base As Cubs, Pirates Start Big Series,” Chicago Evening Post, July 22, 1932, 9. Hornsby discusses the changes in the Cubs lineup in “Cub Star Wounded by Scorned Woman,” Washington Post, July 7, 1932, 3. Game logs are in http://www.retrosheet.org/.

12. Handbills and “solace” quotation are in Edward Burns, “Five Wild Weeks Give the Cubs a Succession of Varied Thrills,” The Sporting News, August 18, 1932, 1. Popovich making her debut and “The Girl Who Shot” quotation are in “State-Congress Has Violet Valli As Star,” Chicago Herald and Examiner, July 24, 1932, sec. 3, 10. Popovich adopting her stage name is in “Letter Solves the Shooting of Bill Jurges.” “Bare Cub Girls” quotation is from “Amusements,” Chicago Herald and Examiner, July 23, 1932, 11. “Bare Cub Follies” and “A Screamingly Funny” quotations are from “Amusements,” Chicago Daily Tribune, July 26, 1932, 11. Articles that refer to Popovich’s show in the past tense include “Girl Who Shot Cub Ball Player Asks Arrest of Agent;” “Girl Who Shot Jurges Battles for His Letters,” Chicago Herald and Examiner, August 13, 1932, 13. Popovich singing and dancing during her show and Mark Prescott quotation are from Mark Prescott (son of Popovich’s brother Mark), telephone interview, November 16, 2015. In a December 26, 2014, email, Popovich’s nephew Peter Prescott wrote that “it is my understanding that Violet’s six-month show…was cut short after the curiosity wore off and due to her lack of talent.” The origin of Popovich’s stage name, Valli, is unknown. Perhaps she was inspired by popular entertainer Rudy Vallee. Another possibility is Ernie Valle, a well-known musical director and orchestra leader of the time. See Steven Suskin, The Sound of Broadway Music: A Book of Orchestrators and Orchestrations (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2009), 487.

13. Popovich seeking a warrant, the “of an affectionate nature” quotation, and publication of the letters for cash are in “Girl Who Shot Jurges Battles for His Letters.” Kiki Cuyler letters are in “Valli ‘Love’ Letters Would Wreck Cubs, Accused Insists,” (Chicago) Daily Illustrated Times,” August 16, 1932, 3. Popovich’s lawsuit (the reasons for it were not given), “I wouldn’t let him do that” quotation, blackmail plot, and “an alleged confidence man” quotation are in “Police Hold Chief of Jurges Blackmail Plot,” Chicago Daily Tribune, August 14, 1932, sec. 2, 2. “I’m a Cub fan myself” quotation is from “Girl Who Shot Cub Ball Player Asks Arrest of Agent.” Barnett’s arrest and charges are in “Arrest Jurges Letter Holder on Girl’s Plea,” Chicago Herald and Examiner, August 14, 1932, sec. 1, 3; “Girl Regains Jurges Notes; Continue Case,” Chicago Daily Tribune, August 19, 1932, 23.

14. Sbarbaro fining Barnett is in “Jurges Letter Suspect Fined on 3 Charges,” Chicago Daily Tribune, August 24, 1932, 18; “Valli Letter Holder Fined; Faces Hearing,” Chicago Herald and Examiner, August 24, 1932, 3. Dismissal of charges and return of the letters are in “Dismiss Extortion Charges in Jurges Shooting Case,” Chicago Daily Tribune, September 9, 1932, 3. The illness of Popovich is in “Jurges Letter Holder Freed,” Chicago Evening American, September 8, 1932. “After two months” quotation is from Ehrgott, Mr. Wrigley’s Ball Club, 347.

15. Articles on Popovich’s altercation include “Blues Singer Sees Red: Charges Pal with ‘Eviction,’” (Chicago) Daily Times, March 11, 1937 (includes “torch singer” and “going” quotations); “She Finds Reason to Sing Blues,” Chicago Evening American, March 11, 1937 (includes “I insisted he let me out” quotation); “Pushed from Auto,” Chicago Daily Tribune, March 12, 1937, 18. Williams’s occupation of “general office work” in his father’s “hardware factory” is in the 1930 U. S. Census (Population Schedule), Chicago, Illinois, Enumeration District (ED) 16-184, sheet no. 39-B, Frederick B. Williams in household of Frank B. Williams, line 52, digital image, accessed November 2, 2015, http://www.ancestry.com/. Marriage application between Fred B. Williams and Violet Popovich is cited in Cook County, Illinois Marriage Index, 1930–1960, file number 1553834, accessed October 20, 2015, http://www.ancestry.com/. Digital image of the “affidavit for marriage license” obtained from the Cook County Clerk’s Office, Genealogy Online, accessed October 21, 2015, http://www.cookcountygenealogy.com/. Popovich using her mother’s name is in Gardner, “Jurges’ Girl Friend Blames Shooting.” “Margaret Heindl” is in the two versions of “Note Reveals Girl Planned to Kill Jurges” (see note 3).

16. Articles that mention Popovich and Jurges include Mike Drago, “Jurges a ‘Natural’ On—Perhaps Off—the Field,” Reading (Pennsylvania) Eagle, August 23, 2009; Tom Weir, “20th Century: This Day in Sports,” USA Today, July 6, 1999, sec. C, 3; “Waitkus Shooting Recalls 1932 Jurges Incident,” Washington Post, June 16, 1949, 20.

17. Legal documents not cited as obtained online are from the Circuit Court of Cook County Archives, Chicago, Illinois. Mirko Popovic was born on April 1, 1881. His ancestry and emigration are in United States Department of Labor, Immigration Service, Certificate of Arrival—for Naturalization Purposes, “Lirko [sic] Popovic,” stamped June 30, 1922 (the January 19, 1907, “date of arrival” is verified in Hamburg Passenger Lists, 1850–1934, accessed June 10, 2016, http://www.ancestry.com/); United States of America, Declaration of Intention, “Mirko Popovic,” no. 79198, December 6, 1917 (notes that Margaret was born in Austria); U.S. Naturalization Record Indexes, 1791–1992 (indexed in World Archives Project), “Mirko Popovic,” accessed May 2, 2016, http://www.ancestry.com/; United States of America, Petition for Naturalization, “Mirko Popovic,” no. 56042, September 5, 1924 (includes names and birthdates of Violet [has incorrect day of March 24], Michael, Milos, and Marco). Fog is in “Lost in New York Harbor,” Washington Post, January 19, 1907, 3. Marriage is in State of Illinois, Marriage License, Mirko S. Popovich and Margaret Heindl, no. 535453, applied for on May 27, 1910 (married on June 5, 1910). Margaret Heindl’s birthday of May 10, 1891, is in California, Death Index, 1940–1997, “Margaret A. Heindl,” accessed November 11, 2015, http://www.ancestry.com/. Violet’s birthday and names of parents are in U. S., Social Security Applications and Claims Index, 1936–2007, “Violet Popovich,” accessed November 20, 2015, http://www.ancestry.com/. Drogiro Popovich’s birth and death are in Illinois, Cook County Deaths, 1878–1939, 1955–1994, “Drogiro Popovich,” accessed November 1, 2015, https://familysearch.org/.

18. Signatures of the Popovich children showing names of Mike Popovich, Violet Popovich, Mark Popovich, and Melvin Parker are in Probate Court of Cook County, In the Matter of the Estate of Mike Popovich, Deceased: Vouchers, document 445, page 443, no. 45 P 7555, stamped July 16, 1947, Circuit Court of Cook County Archives, Chicago, Illinois. Mark Popovich/Mark Prescott is in State of California, Certificate of Registry of Marriage, Mark Popovich “also known as Mark Prescott” and Helen Josephine Thotos, no. 30122, applied for on September 20, 1947 (married on October 1, 1947), Los Angeles County, Los Angeles, California, California, County Marriages, 1850–1952, digital image, accessed November 11, 2015, https://familysearch.org/. Melvin Parker changing his name to Melvin Parker Popovich is in “Order to Show Cause,” Van Nuys (CA) News and Green Sheet, May 19, 1972. Michael Popovich changed his last name to Prescott and had a son, Michael Prescott, as per emails from Mark Prescott (son of Violet’s brother Mark), November 13, 2012; June 16, 2016.

19. Legal documents are from the Circuit Court of Cook County Archives, Chicago, Illinois. “In constant fear” quotation is from Margaret Popovich vs. Michael Popovich, Bill for Divorce, no. B-56160, September 3, 1919. “At that time” quotation and Violet’s testimony are from Margaret Popovich vs. Michael Popovich, Certificate of Evidence, no. B-56160, March 26, 1920. Divorce is in Margaret Popovich vs. Michael Popovich, Decree for Divorce, no. B-56160, March 30, 1920.

20. Legal documents are from the Circuit Court of Cook County Archives, Chicago, Illinois. Michael’s occupation and “unable to support” quotation are from Margaret Popovich vs. Michael Popovich, Petition for Rule to Show Cause, no. B-56160, July 26, 1920. Margaret’s occupation is in the 1920 census, which lists the names of the Popovich family members as Mike, Margaret, Viola, Mike, Milos, and Mark. See 1920 U.S. Census (Population Schedule), Chicago, Illinois, Enumeration District (ED) 1256, sheet no. 7-B, lines 53–58, digital image, accessed October 20, 2015, http://www.ancestry.com/. Four Popovich children placed in the Uhlich Children’s Home in 1920 and just the three boys living there in 1922 and 1923 are in Margaret Popovich vs. Mike Popovich, Petition, no. B-56160, June 27, 1922; Margaret Popovich vs. Mike Popovich, Notice-Petition and Affidavit to Petition, no. B-56160, February 8, 1923. Michael calling Uhlich’s his home is in Henry W. King, Report of Superintendent to Board of Trustees, April 12, 1928, Uhlich Children’s Home Records, series 1, box 1, folder 2, Chicago History Museum (see also King’s report of May 10, 1928, and June 14, 1928). Michael left Uhlich’s on January 30, 1932, and Malosh [sic] and Mark left on June 18, 1932. See Roll Call Ledger: Boys’ Division, 1931–1932, Uhlich Children’s Home Records, series 1, box 3, folder 4, Chicago History Museum. Violet setting the fire is from Mark Prescott, telephone interview, November 13, 2012. Violet leaving Uhlich’s in March 1926 is in Minutes of the Meeting of the Board of Trustees, March 11, 1926, Uhlich Children’s Home Records, series 1, box 1, folder 1, Chicago History Museum. “Whipped for going” quotation is from “Whipped for Staying Out Late, Girl Runs Away,” Chicago Daily Tribune, July 21, 1926, 3.

21. “I was unhappily married” quotation is from “Cub Star Not to Prosecute Divorcee.” “Began pounding” quotation is from “Crazed by Love Woman Tries to Kill Self.” “Mysterious blond companion” quotation, telegram, “if he denies this” quotation, and reference to Violet’s mother are from the two versions of “Note Reveals Girl Planned to Kill Jurges” (see note 3).

22. Details about Anna Sopcak, her marriage to Michael Popovich, and Anna’s daughter Betty are in the extensive testimonies in Anna Popovich vs. Michael Popovich, no. B-175582, decree entered January 14, 1930, Circuit Court of Cook County Archives, Chicago, Illinois. See especially testimony by Anna Popovich (pages 2–69), testimony by Michael Popovich (pages 75–159), and testimony by Betty Carlan, aka Betty Subject (pages 907–25). The 1930 census notes that Anna and her daughter Evelyn went by the name of Subject (a phonetic spelling of Sopcak) and that Betty Carlan was married to Eugene S. Carlan (this was her fourth marriage). See 1930 U. S. Census (Population Schedule), Chicago, Illinois, Enumeration District (ED) 16-1655, sheet no. 23-B, Anna Subject and family, lines 65–69, digital image, accessed November 5, 2015, http://www.ancestry.com/. Betty was born in 1896 and died in 1970. See California Death Index, 1940–1997, “Betty E. Carlan,” accessed November 8, 2015, https://familysearch.org/. Articles about Betty Subject include “Here’s a ‘Pleasant Subject’ in Movies,” (Chicago) Day Book, April 19, 1915, [15]; “Cruelty Alleged by Wife in Suit,” San Francisco Chronicle, November 29, 1923; “September Morn Out of Luck in Winter of San Francisco,” Modesto (California) Evening News, January 5, 1924. Violet and Betty going to New York is in “Crazed by Love Woman Tries to Kill Self”; “Cub Star Not to Prosecute Divorcee”; “Note Reveals Girl Planned to Kill Jurges,” Last Metropolitan edition, 3.

23. Game logs and player statistics are in http://www.baseball-reference.com/ (includes Pacific Coast League statistics) and http://www.retrosheet.org/. Hornsby and Grimm are in Edward Burns, “Hornsby Removed by Cubs,” Chicago Daily Tribune, August 3, 1932, 1, 19; “Why Hornsby Leaves the Cubs,” Literary Digest 114, no. 8 (August 20, 1932): 30; Peter Golenbock, Wrigleyville: A Magical History Tour of the Chicago Cubs (New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1996), 225–31. Hiring of Mark Koenig is in “Koenig Purchased by Cubs; To Join Team Thursday,” Chicago Daily Tribune, August 6, 1932, 13. Koenig biographical information is in Daniel Shirley, “Mark Koenig,” SABR Baseball Biography Project, Society for American Baseball Research, accessed May 24, 2016, http://sabr.org/bioproj/person/560d9b03. Koenig traded to Detroit Tigers is in “Hoyt and Koenig Go to Tigers in Trade,” The New York Times, May 31, 1930, 14. Veeck wanting Koenig is in Arch Ward, “Talking It Over,” Chicago Daily Tribune, August 31, 1932, 17 (includes “hit the first ball” quotation); Joe Vila, “Setting the Pace,” (New York) Sun, August 8, 1932, 23; Claire Burcky, “Castoff Koenig to See Pal, Tony, in World Series,” (Gloversville, New York) Morning Herald, September 8, 1932, 5. Koenig’s single on August 14 is in Edward Burns, “Cubs Lose 2–0, 2–1 Battles to Cardinals,” Chicago Daily Tribune, August 15, 1932, 19.

24. Game logs, team standings, and player statistics are in http://www.retrosheet.org/. “Chicago’s baseball hero” quotation is from Edward Burns, “Homer with 2 On, 2 Out in 9th! Cubs Win, 6–5,” Chicago Daily Tribune, August 21, 1932, sec. 2, 1, 2. The Cubs clinching the pennant is in Edward Burns, “38,000 Cheer As Cubs’ Victory Clinches Flag,” Chicago Daily Tribune, September 21, 1932, 1, 21. “The ball started bouncing” quotation is from Charlie Grimm, with Ed Prell, Jolly Cholly’s Story: Baseball, I Love You! (Chicago: Henry Regnery, 1968), 88.

25. World Series shares are in Edward Burns, “Cubs Split Series Money; Ignore Hornsby,” Chicago Daily Tribune, September 22, 1932, 23; Irving Vaughan, “Home Field Buoys Cubs for Third Game,” Chicago Daily Tribune, October 1, 1932, 19 (mentions that Ruth “kept yelling at Koenig, ‘So they’re going to give you a half share, are they, Mark? Well, you had better collect that five bucks right now.’”); “World Series Gate Receipts,” Baseball Almanac, accessed June 9, 2016, http://www.baseball-almanac.com/ws/wsshares.shtml. “We figured he wasn’t” quotation and “once all that yelling” quotation are from Golenbock, Wrigleyville, 233, 235. “Sure, I’m on ’em” quotation is from “Babe Airs His Views of Cubs and ‘Chiseling,’” Chicago Daily Tribune, September 30, 1932, 21. “The Cubs’ stinginess” quotation is from “Scribbled by Scribes,” The Sporting News, October 13, 1938, 4. Game logs are in http://www.retrosheet.org/.

26. Controversy over third game is in Golenbock, Wrigleyville, 234–39 (Woody English quotation is on p. 234); Robert W. Creamer, Babe: The Legend Comes to Life (New York: Simon and Schuster, 2005), 357–68; Ehrgott, Mr. Wrigley’s Ball Club, 369–71, 451–55; Ed Sherman, Babe Ruth’s Called Shot: The Myth and Mystery of Baseball’s Greatest Home Run (Guilford, Connecticut: Lyons Press, 2014). Game logs and player statistics are in http://www.retrosheet.org/; http://www.baseball-almanac.com/. “I never fit in” quotation is in Shirley, “Mark Koenig.” See also Edward Burns, “Cubs Get Chuck Klein for Cash, 3 Players,” Chicago Daily Tribune, November 22, 1933, 21. “Bullet Bill Jurges” quotation is in “Bill Jurges Leads N. L. Shortstops,” Chicago Daily Tribune, December 28, 1932, 17 (statistics are in “National League Fielding, 1932,” 18).

27. “I guess I’ll remain” quotation is from “Jurges Must Accuse Girl, Says Court,” Chicago Evening American, July 8, 1932. Mary Huyette and games on wedding day are in Edward Burns, “Cubs Idle; Buy Wedding Gifts for Jurges,” Chicago Daily Tribune, June 28, 1933, 25; “Cubs Conquer Phils Twice, 9–5 and 8–3,” The New York Times, June 29, 1933, 24. Game logs, team standings, and player statistics are in http://www.retrosheet.org/. Jurges trade is in Irving Vaughan, “Cubs Get Leiber, Mancuso and Bartell,” Chicago Daily Tribune, December 7, 1938, 25, 27. Biographical information on Jurges is in Geisler, “Billy Jurges” (see note 2); Kenan Heise, “William F. Jurges, Cubs Shortstop in 1930s, ’40s,” Chicago Tribune, March 7, 1997; Rich Westcott, “Bill Jurges—Good Field, Good Hit Shortstop,” in Diamond Greats: Profiles and Interviews with 65 of Baseball’s History Makers (Westport, Connecticut: Meckler Books, 1988), 100–105 (includes “it is very important” quotation on p. 104); Tony Salin, “Chicago’s Blazing Shortstop: Billy Jurges,” in Baseball’s Forgotten Heroes: One Fan’s Search for the Game’s Most Interesting Overlooked Players (Lincolnwood, Illinois: Masters Press, 1999), 159–68; Eddie Gold and Art Ahrens, “Billy Jurges,” in The Golden Era Cubs, 1876–1940 (Chicago: Bonus Books, 1985), 144–47; Rick Phalen, “Billy Jurges,” in Our Chicago Cubs: Inside the History and the Mystery of Baseball’s Favorite Franchise (South Bend, Indiana: Diamond Communications, 1992), 1–4; Stan Grosshandler, “Billy Jurges Recalls How It Was in Majors in 1930s,” Baseball Digest 51, no. 10 (October 1992), 68–70. “It was never mentioned” quotation is from Suzanne Jurges Price, telephone interview, September 21, 2011.

28. 1940 U. S. Census (Population Schedule), Los Angeles, California, Enumeration District (ED) 60–109, sheet no. 9-A, Margaret Heindl and Violet Heindl Popovich, lines 23–24, digital image, accessed October 20, 2015, http://www.ancestry.com/. The 1930 census shows Margaret and Violet living in Chicago. 1930 U. S. Census (Population Schedule), Chicago, Illinois, Enumeration District (ED) 16-1604, sheet no. 12-A, Margaret Heindl and Violet Heindl, lines 47–48, digital image, accessed October 4, 2015, http://www.ancestry.com/. Marriage verified in State of Minnesota, Marriage Record, Charles Retzlaff and Violet Popovich, April 17, 1947, certificate number 0040-323, Clay County, Minnesota, Minnesota Official Marriage System, accessed October 15, 2015, http://claycountymn.gov/ 1147/Marriage-Records. Information on Charles “Charley” Retzlaff is in “Charley Retzlaff,” Minnesota Boxing Hall of Fame—Old Timers, accessed June 8, 2016, http://www.mnbhof.org/Minnesota_Boxing_ Hall_of_Fame/Charley_Retzlaff.html; James P. Dawson, “Crowd of 17,000 Sees Louis Stop Retzlaff and Gain His 27th Straight Victory,” The New York Times, January 18, 1936, 10. “Stunning beauty” quotation is from Mark Prescott, telephone interview, November 13, 2012. Personal features are also in Gardner, “Jurges’ Girl Friend Blames Shooting;” “Jurges Must Accuse Girl, Says Court.”

29. Biographical material and “I was very angry” quotation are from Mark Prescott, telephone interview, November 13, 2012. Nursing home and show girl past are in Peter Prescott, email, December 26, 2014. Violet’s date of death is in U.S., Social Security Death Index, 1935–2014, “Violet Popovich,” accessed October 20, 2015, http://www.ancestry.com/. Grave at Forest Lawn is in Forest Lawn—Hollywood Hills, accessed June 1, 2016, http://forestlawn.com/hollywood-hills/; Violet’s father’s death on October 10, 1945, is in Coroner’s Certificate of Death, “Mirko Popovich,” District no. 3104, no. 28573, stamped October 12, 1945, Circuit Court of Cook County Archives, Chicago, Illinois. Violet’s mother’s death on October 15, 1957, is in California, Death Index, 1940–1997 (see note 17).

30. “She was desperate” quotation is from Ed Hartig, email, January 6, 2016. “The shooting of Jurges” quotation is from Ed Hartig, “The Original ‘Wonder Boys,’” Chicago Cubs Vine Line 18, no. 2 (February 2003): 31 (mentions Waitkus, Jurges, and The Natural). See also Rob Edelman, “Eddie Waitkus and The Natural: What Is Assumption? What Is Fact?,” The National Pastime (2013): 86–91.