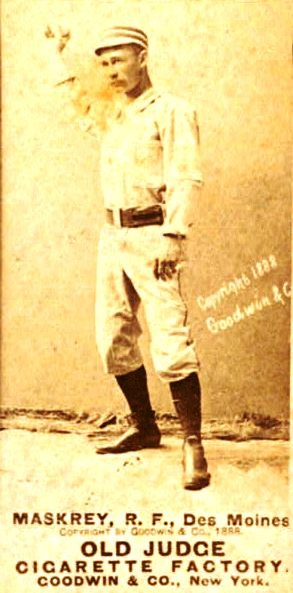

Leech Maskrey

After breaking into the American Association in 1882 at the age of 28, Leech Maskrey had a run of four-plus seasons in the big leagues. During this time he accumulated more than 1,500 plate appearances in 414 games. Maskrey remained active in baseball until he turned 50, with his post-major-league involvement in the sport including a brief spell as a player-manager in Britain. He also engaged in numerous vocational and recreational pursuits, both during and after his baseball career.

After breaking into the American Association in 1882 at the age of 28, Leech Maskrey had a run of four-plus seasons in the big leagues. During this time he accumulated more than 1,500 plate appearances in 414 games. Maskrey remained active in baseball until he turned 50, with his post-major-league involvement in the sport including a brief spell as a player-manager in Britain. He also engaged in numerous vocational and recreational pursuits, both during and after his baseball career.

Samuel Leech Maskrey was born on February 11, 1854, in Mercer, Pennsylvania. His father, William Maskrey, was a stonecutter who had moved to Mercer to supervise construction of a county courthouse. Little is known of Leech’s early years. However, his life immediately before, during, and after his spell in the majors is well documented.

After playing in the early 1880s for the Akrons, an independent team in Ohio that proved to be a formidable propagator of future major leaguers, the 5-foot-8, right-handed batting and throwing outfielder joined the Louisville Eclipse of the American Association in 1882. Maskrey made his debut on May 2. Later in the season, his 20-year-old brother, Harry, joined the team for a single outing. In what proved to be the only game of his major-league career, Harry Maskrey went 0-for-4 and made an error on his solitary fielding chance, in the outfield.

Leech Maskrey was not a strong batter: the “highlight” of his major-league career was a .250 batting average and .281 on-base average with Louisville in 1884, and he managed only two home runs in his 1,601 career at-bats. However, he could more than hold his own defensively. Maskrey had the fourth best fielding average among American Association outfielders in both 1882 (.902) and 1883 (.914). In the latter season he led the circuit in putouts by an outfielder, with 193 in 96 games. In May 1886 Maskrey was released by Louisville after playing in five games. He joined the Cincinnati Red Stockings of the American Association. Toward the end of the season, though, his career path dropped down to a minor-league level.

In 1888, while playing minor-league ball with Milwaukee of the Western Association, Maskrey was managed by Jim Hart. Hart and Maskrey had been manager and player in Louisville as well.[1] Maskrey was released by the brewing city’s team at the end of the 1888 season, with his poor batting being cited as the principal objection against him.[2] Nevertheless, his fielding at Milwaukee earned him a reputation as “one of the most conscientious and steadiest players in the business,” and he was said to have been “well liked” by Hart.[3] Indeed, they were reported to have been close friends throughout the overlap in their baseball careers.[4]

Maskrey’s talents extended beyond the baseball field. In Louisville he was described in a local paper as “a man of more than ordinary literary attainment[,] a finished artist at the easel, and a musician of no mean ability.” In Milwaukee his passion for Shakespeare and Dickens was noted, and it was said that he devoted “all of his spare time to painting in water colors” together with Hart’s wife, who was “herself an artist of no small merit.”[5] Away from the easel, Maskrey reportedly had intentions to publish at least two books, one a narrative of his time as a major leaguer in Louisville and the other a novel titled The Ball Players’ Board Bill. The impetus for the former may have been quelled when he was released by the team, while one report from 1887 suggests that the latter was finished but then rejected by the publisher Maskrey had approached. It was said in the same report that Maskrey had carried the manuscript and blank paper with him in a suitcase as he traveled from town to town with his baseball team.

After his sojourn in Milwaukee, the next substantial chapter in Maskrey’s baseball life came in 1890, when he was selected as one of several coaching envoys to travel to Britain in order to provide assistance with a fledgling professional circuit on the other side of the Atlantic called the National Base Ball League of Great Britain.[6] Albert G. Spalding’s sporting-goods company acted as agent in the United States for the recruitment of these envoys, and Spalding became a key shareholder in three franchised teams in the league (a fourth team was operated with financial independence). Spalding leaned on Jim Hart in organizational matters relating to the British league, and it is plausible that this association increased Maskrey’s chance of success in applying for a role as a baseball coach. That is not to say, though, that the man from Mercer was a weak candidate for the trip to Britain.

Maskrey arrived relatively late in the buildup to the pro circuit (landing on the Umbria in April) and was sent to coach the team in Preston, the league’s northern outpost. Nevertheless, he made swift progress in preparing his team, which predominantly comprised native soccer players with no baseball experience (the team shared personnel and a field with the Preston North End Football Club, one of the dominant forces of English soccer at the time). Such was the quality of the preseason work in Preston that his peers regularly offered kind words on Maskrey’s progress. On May 12, for instance, the coaching envoy assigned to the Aston Villa baseball team observed that Maskrey had “accomplished wonders” in a short period of time and had “caught the people of Preston” with his “wonderful” fielding.[7]

As player-coach, Maskrey placed himself behind the plate, since this was not a position for any of his native novices to play. However, the Preston nine had to rely on a native arm in the box. In contrast, the other three teams in the circuit all had a pitcher from the United States to employ. One of these pitchers, John Reidenbach of Derby, was so effective that the resulting imbalance in the competition began to rile Maskrey and his team. Partway through the season, an agreement was reached stipulating that imported pitching should be used only when Derby, the strongest team in the circuit, played Aston Villa, the next best outfit. Eventually, though, the agreement was broken, and the chain of events that followed culminated in Derby’s owner withdrawing the team from the league. Derby’s removal left Aston Villa and Preston to scrap for the title, with the third remaining team, Stoke, a bad tailender. The battle for the championship went to the final weekend, but Maskrey’s team ultimately lost out.

Maskrey posted a .347 batting average in the league, but this was bettered by nine other players, seven of them natives. He did lead the league in runs, though, with 74 in his 35 games. Furthermore, he hit at least five home runs, more in one season than in his whole major-league career. (Some box scores gave no listing of extra-base hits, and others have not been found.) His extra-base exploits included a pair of homers in one game and a grand slam in another (he was aided somewhat by three of the four fields used being smaller than usual baseball diamond, owing to their confinement within the bounds of a soccer ground). But it was for his coaching that he was best remembered. Before his departure at the end of the season, he was presented by his team with a “valuable gold chain.” Even the journalists covering Preston’s rival teams expressed sincere praise for the improvements he brought about in his rookies despite having to coach the nine singlehandedly.

Maskrey began the return voyage to his native land on September 6, 1890, after a brief excursion through Ireland with Jim Hart as a traveling companion.[8] (Meanwhile, for a number of reasons, the league folded, although baseball continued to be played in the country.) By February 1891, a month in which Maskrey celebrated his 37th birthday, he had secured his next baseball appointment, signing as player-manager of the Pacific Northwest League’s Tacoma Daisies.[9] While a .200 batting average for the season may have disappointed the aging Maskrey, one remarkable victory gave him reason to be proud of his managerial contribution.

In May Tacoma hosted Seattle in a game that stood tied, 4–4, after nine innings. The game moved into extra innings, and frame after frame Maskrey’s team neither conceded nor scored. In the 17th, both sides plated a run, but there was no further scoring until the 22nd inning. In that frame, a solitary Tacoma runner crossed the plate and that proved sufficient to give Maskrey’s nine the contest. Charles Maskrey, a brother of Leech, later recalled that the game had gripped baseball lovers in the region; for example, 1,500 people had stood watching news of the score on the bulletin boards in Seattle. The relative also remembered it to have been the longest professional game on record at the time.[10] But marathon contests were nothing new for Leech Maskrey. In 1881, he played for the Akrons in a 19-inning 2–2 tie with the Louisville Eclipse.

By early 1892 Maskrey had returned from Tacoma to his birthplace of Mercer, and in late January was wedded to a hometown resident, Ollie Golf, at a small ceremony. Golf was described in Sporting Life as being “one of the fairest, most popular and talented of the many lovely young ladies of this city.”[11] This life-changing event did not appear to lessen Maskrey’s appetite for baseball. Just a few weeks later, he was present at a meeting called in Meadville, near Mercer, with the intention of resurrecting a defunct regional league.[12] And by late March he had been appointed as manager of the Atlanta Firecrackers of the Southern League for the 1892 season.[13]

Sporting Life reported great enthusiasm in the Georgia city surrounding the acquisition of a manager “who knows every point of the game thoroughly.” This complemented ambitious plans to develop the club’s ballpark into the “finest in the South.”[14] According to baseball historian Richard McBane, however, after several player injuries and a run of poor results, Maskrey soon lost popularity with the local baseball community (in the latter half of the 19th century, the same fate was met by many other “Yankees” making a Southern diversion on their baseball journeys). McBane cited a passage from the Sporting Life to exemplify Maskrey’s plight, and it is a story that suggests the early optimism was rapidly nullified: “From the first there has been a crowd of fans working against him, and they had two evening papers working with them. The result was that he has been blamed for everything. To-day, while he was coaching, a runner was caught napping. Then the crowd of fanatics in one corner of the grand stand […] jeered and hissed Atlanta’s manager.”[15] He might have wished during this game that he was back in Preston being cheered on by the devoted home crowd. In June, Maskrey resigned from his Atlanta post, stating that his presence appeared to be detrimental to the interests of the club.

The experience in Atlanta appeared to have brought Maskrey’s interest in baseball to an end. In 1893, an article reviewing the whereabouts of players from the American Association of 10 years earlier noted that Maskrey had left the game and was an art teacher.[16] But Maskrey’s conversion of his creative passion into a vocation proved to be merely an intermission in his baseball life. In 1895 his name was in the sports section once more. This time it was for his fundraising activities relating to the new Iron and Oil League. Maskrey’s aim was to secure the last remaining spot for Meadville over the rival locations of New Castle and Jamestown, and his groundwork was said to have made Meadville the favorite in that three-town race.[17] History reveals that it was New Castle, though, that secured the berth in 1895.

Meadville would get a team in the circuit but not until 1898, which was a season of historical significance for the league from a social angle. One of the entrants was the Acme Colored Giants, of Celoron in New York State, and, according to research by Merl Kleinknecht in the 1970s, they were the last team of black players in organized “white” baseball. After 1898, Kleinknecht’s research indicated, there were no black players in the minor leagues until Jackie Robinson entered the International League in 1946.[18] Another team in the 1898 Iron and Oil League was from Warren, Ohio. This is the town where Maskrey’s time in baseball at last came to an end. He managed the Warren team for “three successful seasons” shortly after the turn of the century, and in 1904—the year in which he turned 50—brought an end to his career.[19]

A year later, Sporting Life reported that Maskrey had been an engineer on a train that crashed on September 7 and that he had been killed.[20] The reality, however, was that he had either survived or not been involved at all, for he lived on until 1922. During his post-baseball life, Maskrey devoted energy to politics[21], and he was also a hotelier[22] and a pool hall owner.[23] In March 1922, Maskrey became confined to his Mercer home, probably suffering from congestive heart failure, and he passed away on April 1.

Sources

In addition to the specific references cited within this biography, the author made general use of the following sources:

Gray, Joe. What About the Villa?: Forgotten Figures From Britain’s Pro Baseball League of 1890. Ross-on-Wye, United Kingdom: Fineleaf Editions, 2010

McBane, Richard. A Fine-Looking Lot of Ball-Tossers: The Remarkable Akrons of 1881. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Co., 2005

The author would like to express gratitude to fellow SABR member Josh Chetwynd for his assistance with literature searching.

[1] Evening Record (Greenville, Pennsylvania), July 21, 1919.

[2] Sporting Life, February 20, 1889.

[3] Ibid,

[4] Evening Record (Greenville, Pennsylvania), July 21, 1919.

[5] Daily Northwestern (Oshkosh, Wisconsin), August 27, 1887.

[6] Gray, Joe. What About the Villa?: Forgotten Figures From Britain’s Pro Baseball League of 1890. Ross-on-Wye, United Kingdom: Fineleaf Editions, 2010.

[7] Ibid.

[8] Sporting Life, September 27, 1890.

[9] Sporting Life, February 14, 1891.

[10] Anaconda (Montana) Standard, May 26, 1904.

[11] Sporting Life, February 6, 1892.

[12] Bradford (Pennsylvania) Daily Era, March 11, 1892.

[13] Sporting Life, March 26, 1892.

[14] Ibid.

[15] McBane, Richard. A Fine-Looking Lot of Ball-Tossers: the Remarkable Akrons of 1881. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Co., 2005.

[16] Sunday Herald: Syracuse, September 17, 1893.

[17] Titusville (Pennsylvania) Morning Herald, April 4, 1895.

[18] Kleinknecht, Merl. “Blacks in 19th Century Organized Baseball.” Baseball Research Journal, 1977.

[19] Evening Record (Greenville, Pennsylvania), July 21, 1919.

[20] Sporting Life, September 16, 1905.

[21] Evening Record (Greenville, Pennsylvania), January 29, 1907.

[22] Record Argus (Greenville, Pennsylvania), September 22, 1941.

[23] Evening Record (Greenville, Pennsylvania), May 5, 1916,

Full Name

Samuel Leech Maskrey http://dev.sabr.org/?p=61695

Born

February 11, 1854 at Mercer, PA (USA)

Died

April 1, http://dev.sabr.org/journal/article/appendix-1-the-three-or-was-it-two-400-hitters-of-1922/ at Mercer, PA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.