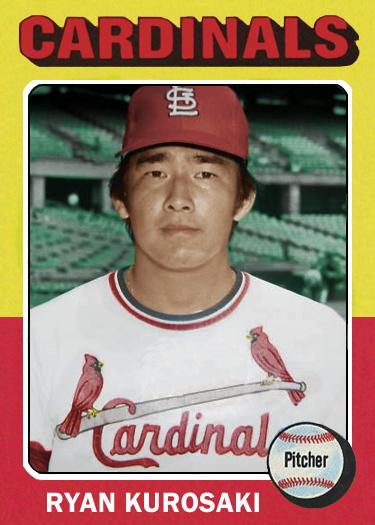

Ryan Kurosaki

Hawaiian reliever Ryan Kurosaki was the third American of Japanese Ancestry (AJA) to play major-league baseball — but the first of 100% Japanese descent.1 His time at the top was brief — seven games with the St. Louis Cardinals in 1975 at age 22. The Cards called up the righty from Class AA early in his second pro season. After that five-week stint, the highest he got in his remaining five years was Class AAA.

Hawaiian reliever Ryan Kurosaki was the third American of Japanese Ancestry (AJA) to play major-league baseball — but the first of 100% Japanese descent.1 His time at the top was brief — seven games with the St. Louis Cardinals in 1975 at age 22. The Cards called up the righty from Class AA early in his second pro season. After that five-week stint, the highest he got in his remaining five years was Class AAA.

Yet Kurosaki’s niche in baseball history has been acknowledged. As author Samuel Regalado put it, “Ryan Kurosaki was an unassuming pioneer who brought with him, in spirit, generations of Nikkei [Japanese immigrant] ballplayers whose devotion to the game was overshadowed only by their love for their country.”2

Kurosaki is a sansei, or third-generation Japanese American. His grandparents all emigrated from Japan early in the 20th century. His father and his mother were both born on the Big Island of Hawaii. Katsuto Kurosaki, a carpenter, moved to Oahu when he was around two years old.3 He married Toshiko Fujii (who took the English name Eleanor) in 1946. Eleanor stayed home with her two sons, Neal and Ryan, while they were young. She then worked in retail for many years until retirement.4

Ryan Yoshitomo Kurosaki was born in Honolulu on July 3, 1952, a little more than seven years before Hawaii gained statehood. He grew up in Kaimuki, a place whose distinct character has won it frequent description as a town or village within the capital city. Noting how slowly change came to Kaimuki, in 1996 the Honolulu Star-Bulletin described it as “a neighborhood of longtime residents and small shops that, for the most part, minds its own business.”5 Those shops included Tanoue’s Saimin (a favorite purveyor of the broadly popular Hawaiian noodle soup) and many okazuya (sellers of various multicultural side dishes to eat with rice).6

Baseball was part of the social fabric in Kaimuki too — every district had its own youth team. “It was just a nice friendly community,” said Kurosaki. “It was a neat time and a neat place. It’s changed but it’s held onto that feeling.”7

Japanese was spoken in his house growing up, “but my dad and I weren’t very good. I went to Japanese school for about four years, but I faded out with baseball. My parents spoke it when they didn’t want the kids to understand. I went to Japan one year and they could tell I was from Hawaii!”8

Though Katsuto Kurosaki didn’t play baseball, he dearly loved it and encouraged his sons. Ryan came up through the usual ranks, playing Little League, Pony League, Colt League, and American Legion ball. “My dad coached at the Little League level, up until we were about 12, and my older brother played, so I just followed suit. We grew up in town, we’re not talking the picturesque countryside.” But even though Kurosaki compared his boyhood baseball experience to that of almost any youngster, there was in fact a local twist. “My brother was in the AJA League [the local rec league for Japanese Hawaiians], and my dad used to take me. That’s what we did on Sunday afternoons, watched the AJA League.”9

Pitcher Masanori Murakami became the first Japanese big-leaguer in 1964, and Kurosaki remembered hearing his name while listening to a San Francisco Giants game during a fishing trip with his father. “But it didn’t really make an impact on me,” he said. “I was probably too young at the time. It wasn’t built up in Hawaii.”10

Kurosaki’s youth teams were successful, and he got to travel to California and Oregon as a result, But not long after he turned 14, he got a special treat: playing in Pony League regional competition at Honolulu Stadium. His team, Honolulu PAL American, beat Walla Walla, Washington, 7-3. Though he gave up a two-run homer in the first inning, he pitched the remaining six, striking out 10 and walking just one. He helped himself at the plate with a single, double, and triple.11

It was especially meaningful to pitch at quaint Honolulu Stadium. In addition to its unique atmosphere, Kurosaki had learned much about baseball by going to games with his father every Friday night when the Hawaii Islanders of the Pacific Coast League were at home. “Growing up during those years, it was the ultimate for us.” He remembered that after playing on rough local fields, the manicured professional surface was striking.12

As a senior in 1970, Kurosaki was the star pitcher and league MVP for the state champion Kalani High team. Again he got to pitch at Honolulu Stadium.13 He chuckled modestly when asked about that accomplishment. “I think especially for me, being of Japanese ancestry, things like professional ball were just miles away. No one had really set a precedent, and academics were a high priority with my folks.”14

Another future big-leaguer and fellow AJA, junior Lenn Sakata, had Kurosaki’s back at shortstop. “He was captain of our team,” said Sakata in 2002 (the Falcons actually had tri-captains). “We looked up to him. He was the leader.”15

“Kurosaki had a wicked breaking pitch,” another Kalani teammate, Steve Kimura, told author Kerry Yo Nakagawa. Ryan himself also spoke to Nakagawa. “I have lots of memories, good memories, of pitching for that team,” he said. “When looking back, it was a great baseball team.” He added that playing for Kalani coaches Herb Okamura and Ralph Takeda was a great learning experience. Nakagawa described that championship season as a springboard to Kurosaki’s success at the collegiate level and beyond.16

The next step was winning a baseball scholarship to the University of Nebraska. “An alumnus who lived in Hawaii recruited me, or at least got Nebraska interested in me.” That alum was a man named Dave Murakami, who’d played shortstop for the Cornhuskers in the late ’50s and was still playing local ball in Honolulu. Kurosaki was his teammate.17 (Murakami later became an assistant coach at the University of Hawaii.) Kurosaki also said, “I probably wouldn’t have gone if my parents hadn’t insisted on it; they wouldn’t take no for an answer. Anyway, I enjoyed it. Snow was different.”18

Ryan had played football for Kalani — “one season at cornerback, at a massive 140 pounds!”19 However, the Huskers were and are known as a college football powerhouse, so his reason for being in Lincoln was clear. Still, he benefited from the first-rate football program. “At the time, the early to mid-’70s, I don’t think weights were stressed as much. I fiddled with weights at Nebraska just because I wanted to get stronger, not for bulk. The trainers there knew exercises that were ideal for strengthening certain parts of the arm for quarterbacks. They mentioned that I should start doing some of this stuff, and I think it helped as far as not having a whole lot of injuries.”20

Nebraska baseball coach Tony Sharpe described Kurosaki as a freshman in the spring of 1971. “He needs some experience with his control. Once he gets some experience under his belt, he’ll have better control of his breaking stuff.” Sharpe added, “He’s willing to work and that is a good sign.”21

Kurosaki posted consistently reliable performances; in three seasons (1971-73), his records were 4-3, 3-2, and 5-3, with ERAs of 2.70, 2.75, and 2.67. He set a team record with four career shutouts. Coach Sharpe noted that “he has several pitches. Counting different speed curves, I guess you’d say about six. And he keeps ’em in the strike zone.” Kurosaki walked just 13 batters in 56 innings in 1973.22 He stated, “Going to Nebraska set everything in motion — being able to play at a higher level, having some success there gave me an opportunity to go professional.”23

Another key to Kurosaki’s ascent was joining a top-rank semipro club, the Liberal (Kansas) Bee-Jays, then coached by former major leaguer Bob Cerv. This team regularly competed in the National Baseball Congress (NBC), a tournament held each summer in Wichita, Kansas, since 1935. Kurosaki’s two-year record with the Bee-Jays was 24-0, and he was a major reason why the club finished third in the 1972 tourney and second in ’73, going 3-0 with two shutouts. He was the Kansas Semi-Pro Player of the Year in ’72. He was also named top pitcher of the 1973 NBC tourney, even though he did not pitch after the quarter-finals. Not wishing to overtax the young hurler’s arm, Bob Cerv told him he was done for the tournament.24

Major-league scouts are always on hand at the NBC, which has sent dozens of young men to the big time. On August 26, after the 1973 tournament ended, Byron Humphrey of the Cardinals signed Kurosaki, who had not been selected in the amateur draft that June. The team’s bird dog in Hawaii, Leland Blackfield, had noticed the pitcher previously. Blackfield recalled, “I went to Nebraska on my own. . .saw him pitch, and he threw nothing but strikes. . . and made ’em pop up his slider and change-up.”25

Yet Kurosaki was unaware that the scout was watching. “I never thought I would get a chance,” he said. “I never got any feelers.”26

Since Kurosaki had signed with St. Louis, he lost eligibility for his final collegiate season.27 The conscientious young man felt bad that he had not given Coach Sharpe enough time to recruit another pitcher, though he later found out that (as one might expect) Sharpe was delighted for him.28

“I went back for the fall semester to Nebraska, but then I went to spring training, and I never did graduate. It was probably more important to my mom than my father. He loved baseball. And Byron Humphrey said, ‘If you don’t sign now, you may never get another chance.’ I had 24 hours to make the decision. Nobody to consult, nobody to steer me. My family and I all agreed that I should give it a shot.”29

The young hurler started his pro career in the summer of 1974. From the beginning, St. Louis had a bullpen role in mind for him. He adapted very well and made just eight starts in 303 games as a pro. Looking back in 2002, he downplayed his Japanese descent, saying, “When you get on the field, it’s basically you’re competing against the opposition. I really didn’t have much time to think about it.”30 At Class A Modesto in the California League in 1974, he was 7-3 with a 2.28 ERA and six saves. His manager, Lee Thomas, said “Ryan has a great slider, and he keeps the ball low.”31

When Kurosaki continued to pitch well at Double-A Arkansas in 1975, reeling off 18 straight scoreless innings, the big club called him up in mid-May. “Probably at the time I had the best numbers in the organization,” he said. “I think they felt John Denny, who was struggling, needed some work in Triple-A, and none of the pitchers there were putting up good numbers.”32 Reliever Elias Sosa took Denny’s place in the Cards rotation.33 However, that experiment lasted for just one start.

Leland Blackfield also noted, “At the beginning of the season. . . we (the Cardinals) were having trouble in the bullpen. Anyway, Bob Kennedy [then the Cardinals’ director of player personnel] tipped me off they were gonna call him up, so I contacted him (Kurosaki). First thing I know he says, ‘I know, Mr. Blackfield; they just gave me a ticket!’”34

Blackfield added that the righthander had “the best change of any kid in the big leagues. It’s an A-plus for him. . . If I was a big-league manager, I don’t see how I could keep him on a farm (club). Let’s face it, if a kid doesn’t make it in two or three years at the most, there’s no use kiddin’ yourself.” With regard to Kurosaki’s call-up, he said, “It’s a treat that pays its dividends by just being there in the majors. It’s an education that you couldn’t buy for a young kid.”35

As it turned out, Blackfield’s remarks came just a couple of days before the Cardinals sent Kurosaki down, never to return to the majors, Looking back on his days in St. Louis, Kurosaki mused that it was like Hawaii in one way: it felt like a different world, even though he’d traveled only about 400 miles. “I think everything was so new to me — I never was able to really soak everything in. Maybe I was still in shock for the whole time I was there. You walk out into Busch Stadium and you think, ‘Man, what am I doing here?!’ You wake up one day, you’re pitching at Ray Winder Field in Little Rock. The next day, you get on a plane, you get off in another city, take a cab, and you walk into this incredible ballpark.”36

Kurosaki told Kerry Nakagawa, “I was in awe when I reported. I walked into the locker room, and here are my teammates, Lou Brock and Bob Gibson.” In addition to the Hall of Famers, Kurosaki singled out veteran first baseman Ron Fairly. “He was my roommate on the road, and I learned a lot from him also.”37

Yet in 2019, Kurosaki talked about how alone he was upon arriving in St. Louis. “I had no place to stay, no advance money, no help. I didn’t have any connections because I had no interactions from spring training. I was still at the ballpark after the game, wondering what I was going to do. I thought, ‘Is this the big leagues?’ Fortunately, the third base coach, Vern Benson, said to come back with him to his hotel.”38

In this vein, Kurosaki also discussed his manager, Red Schoendienst. “Looking back, I was filling a spot until John Denny got back on track. I don’t think much was expected of me. I never had any personal conversations with Red about what my role would be. Today, there’s more communication, more one-on-one interaction. I didn’t get that.”39

In his book Nikkei Baseball (2013), Samuel Regalado quoted Lenn Sakata on what Kurosaki’s call-up meant. “Historically there haven’t been many Asian American players in the big leagues. I remember we got really excited when Ryan played. There haven’t been many others since.”40

Regalado noted that Kurosaki and Sakata helped Japanese Americans attain visibility in the big leagues.41 He also put their ethnicity in context. In the early 20th century, when many Japanese immigrants first arrived in the U.S., “the national pastime was a key ingredient in the creation and stability of their young community. As their descendants approached the end of the twentieth century, a time when, by most gauges, the Japanese American community had grown thin, Kurosaki’s uneventful appearance in the big leagues was one of the first important stepping-stones in the new collage of Japanese identity.”42

Kurosaki’s first big-league outing came on May 20 against the Padres in San Diego. Although he walked three in 1 2/3 innings, he gave up no hits and no runs. According to Regalado, the debut was low-key; it was not reported in the Japanese American newspapers at the time. “Kurosaki’s path breaking entry into the big leagues was only unassuming to the Nikkei because their community had, by then, changed from its pre-Second World War identity as a strictly Japanese American enclave to a much wider Asian American profile from which baseball’s prominence played a less distinctive role.”43 If the Hawaiian papers mentioned it, Kurosaki didn’t see them, and his parents didn’t mention anything of the sort.44

On May 25, at Los Angeles, came the appearance that Kurosaki called his highlight in the majors. “Pitching in front of 50,000 people in L.A., and my folks were able to come up and see me.”45 He added that it was a surprise visit. After the Padres series ended, teammate Ted Sizemore, who’d taken the rookie under his wing, had invited Kurosaki to his home in Brea, California (in nearby Orange County). “I got to the hotel, and the traveling secretary said, ‘Hey, Ryan, where’ve you been? Your parents are here.’”46 He mopped up the last two innings of a 7-3 loss, allowing only a home run to Joe Ferguson.

Kurosaki stuck around for another month, getting another surprise visitor — Coach Sharpe of Nebraska — at Cincinnati’s Riverfront Stadium. However, he got into just five more games. All told, he did not receive a decision and gave up 11 runs, including three homers, in 13 innings for a 7.62 ERA.

On June 1, facing the Reds at Busch Stadium, Kurosaki got a different kind of surprise when he was called for a balk. It stemmed from his pickoff move, which he’d learned from a teammate who’d played in Japan. “I’d been using that move ever since high school and I never had a balk called on me before. It was unusual — kind of a hop with a quick release, all wrist — and they’d never seen it before.”47 As seen later that year in the World Series with Luis Tiant, a pitcher with an unusual move who was new to one of the major leagues could be subject to closer scrutiny.48

Kurosaki’s last outing in the majors came at Pittsburgh’s Three Rivers Stadium on June 16. Schoendienst was ejected for arguing with first-base umpire Paul Runge after Runge called another balk. “The kid has a quick move off the mound,” Schoendienst said after the game, demonstrating with choreography. “Some umpiring crews don’t realize that.” Pittsburgh manager Danny Murtaugh said, “I thought it was a balk. Let him show me movies that it wasn’t.” The Cardinals claimed that film would indeed vindicate Kurosaki.49

It didn’t matter, though — a few days later, St. Louis returned Kurosaki to Arkansas. Denny, who had indeed gotten back on track, was recalled.

“It was one of the silliest things the Cardinals ever did,” said Bill Valentine, then the announcer for the Travelers and later the team’s general manager from 1976 through 2008.50 “Here was a kid who had pitched one year in A ball, a few weeks in Double-A, and they pulled him up to pitch relief in the big leagues. No way he could have been ready. Then they sent him back and forgot about him.”51

The Cards added Kurosaki back to the 40-man roster at the end of August 1975, after he’d continued to pitch well for Arkansas. However, the brief news item noted that he was not scheduled to report to St. Louis.52 After spring training in 1976, Kurosaki again found himself assigned to Arkansas, and he never got another chance at the majors. “I’ve thought about this a lot,” he said in the middle of the ’77 season. “I’ve inquired a little but I don’t really know the answer. I don’t even know what the people in St. Louis think of me now…if I’d had a chance at Triple A and bombed out, then I wouldn’t be complaining.”53

At 5-feet-10 and 160 pounds, Kurosaki’s size stacked the odds against him, especially because he wasn’t a fastball/strikeout type of pitcher. However, he told Kerry Nakagawa, “Today, the players are bigger, stronger and faster, but they have some problems. They don’t have the same reverence for the game that we had.”54

The Travelers were also something of a throwback — a minor-league club with a core of players who returned year after year, seemingly with an eye toward pleasing the local fans. One of those enduring teammates, who won three Texas League championships from 1977 through 1980, was future big-league manager Jim Riggleman.

“I see no point in complaining about it or even talking about it now,” said Kurosaki, who was invited to throw out the first pitch of the Travs’ home season in 1996.55 It may have been a professional disappointment to stay in Arkansas — who could blame a competitive young man in his twenties? Yet the personal rewards were greater. “I enjoyed the people in Arkansas, Little Rock especially. I really had a good experience, really made some good friends.”56 The best of those friends was Sandra McGee, whom he met in church in 1975 and married three years later.

Kurosaki asked to be traded when he found that he would be starting his fourth straight season at Arkansas. “They (the Redbirds) told me I had a choice — Arkansas or the Mexican League. Well, I pitched in Mexico during the winter and I wasn’t exactly itching to get back.”57 Later, however, he came to value his south-of-the-border memories, even though he suffered his first arm injury there in ’78. “I’ll never forget my time in Hermosillo. The people there are really excited about their baseball, they love it. But Mexico is Mexico! The crazy things that happened down there, some of the things we went through, you’ve got to experience it — I can’t tell you and give it justice.”58

In addition to Mexico, Kurosaki also played in the local Hawaiian leagues during the winter. “I played for the Asahis for one year, and I was in the AJA League for two years. I played in the Puerto Rican League too, which was a little bit higher caliber, with people like Johnny Matias and Joey DeSa [Hawaiians of Puerto Rican descent], as well as Freddy Kuhaulua and Lenny [Sakata]. We’d all go home, we’d work out, put a team together and play ball. We scrimmaged at the University of Hawaii. I’d say the caliber was between A and AA.”59

Kurosaki did finally get to move up to the top farm club, Springfield, in 1978. He stayed with that team all of the next year. Struggling with arm problems, however, he retired after the 1980 season. During that last year, spent mainly with Arkansas, he faced two rising stars in the Texas League, Fernando Valenzuela and Orel Hershiser.

Kurosaki was a member of the Little Rock Fire Department from 1982 through 2014.60 The idea of becoming a firefighter came to him during a bus trip in the minors, when he and teammates were discussing their future.61 He told Kerry Nakagawa, “Putting out fires in the real world is a lot riskier than being out on the major-league diamonds.”62 He laughed when asked in 2000 if he planned to keep on working. “I’ve got three sons [Jason, Drew, and Aaron]: one in college, one in high school, and one in the sixth grade — what do you think?”63 Two of the boys played baseball, but Ryan let them pursue whatever sports they chose. He gets back to Hawaii about every two or three years, and even though his speech picked up a touch of Southwestern twang, his loyalty is permanent.

“I go home now and I meet some of my friends from years and years ago, and this is what I tell them. I’ve been gone longer from Hawaii than I lived there, but I still consider it my home, because I was born and raised there and I have such fond memories. The thing that stands out is that I’m grateful for the opportunities that I’ve had, the coaches who were able to leave a little bit of themselves in me. In retrospect, it’s remarkable to remember all the people who were willing to give the time, the faces of the fans too.

“To think that I’m the first [100% AJA in the majors], it’s God’s grace. Lenny could easily have been first [Sakata arrived in July 1977].

“I don’t know why it was me. I’m just a normal average guy who got a break.”64

Last revised: August 20, 2019

Acknowledgments

Special thanks to Ryan Kurosaki for his memories (telephone interviews with Rory Costello, March 2, 2000 and August 4, 2019).

Mahalo as always to Donna L. Ching for her help in giving the BioProject’s Hawaiian stories authentic local color.

This biography was reviewed by Warren Corbett and Jan Finkel and fact-checked by Alan Cohen.

Sources

Ryan Kurosaki file from National Baseball Hall of Fame library.

www.huskers.com (University of Nebraska sports website)

www.pannervault.com (Alaska Goldpanners historical website, which includes a page on the 1973 National Baseball Congress tourney)

Notes

1 The first, Mike Lum, was adopted as a baby by a Chinese couple. For many years it was not known that Lum was the son of a Japanese woman and an American soldier. The second, Bobby Fenwick, was born in Okinawa to a Japanese mother and an American father.

2 “The ‘Nikkei’ path breaker with the St. Louis Cardinals,” University of Illinois Press blog, April 8, 2013 (http://www.press.uillinois.edu/wordpress/the-nikkei-path-breaker-with-the-st-louis-cardinals/)

3 Telephone interview, Ryan Kurosaki with Rory Costello, March 2, 2019 ((hereafter Kurosaki-Costello 2019 interview)

4 “Obituaries,” Honolulu Star-Bulletin, September 13, 2000. “Eleanor Toshiko Kurosaki,” Ashby Funeral Home (https://www.ashbyfuneralhome.com/obituary/4062698), January 2017. Kurosaki-Costello 2019 interview.

5 June Watanabe, “Kaimuki on the Rise,” Honolulu Star-Bulletin, April 23, 1996.

6 E-mail from JoAnn Miyagawa via Donna L. Ching to Rory Costello, June 26, 2019.

7 Kurosaki-Costello 2019 interview.

8 Kurosaki-Costello 2019 interview.

9 Telephone interview, Ryan Kurosaki with Rory Costello, March 2, 2000 (hereafter Kurosaki-Costello 2000 interview).

10 Kurosaki-Costello 2019 interview.

11 “PAL Nine Tops Walla Walla, 7-3,” Honolulu Advertiser, August 9, 1966: 21.

12 Kurosaki-Costello 2019 interview.

13 Kurosaki-Costello 2019 interview.

14 Kurosaki-Costello 2000 interview.

15 Stacy Kaneshiro, “Kalani’s Sakata, Kurosaki major achievers,” Honolulu Advertiser, August 15, 2002. Tri-captains are visible in the Journal of Hawaii’s Legislature for 1970.

16 Nakagawa, Japanese American Baseball in California (Charleston, South Carolina: Arcadia Publishing, 2014), page number not available on Google Books.

17 “Husker Pitching Staff May Be Tops in Big 8,” Lincoln (Nebraska) Star, March 24, 1971: 19. Murakami also landed one of the other Kalani tri-captains, shortstop Bryant Akisada, for Nebraska.

18 Jim Bailey, “Kurosaki Played Fireman During Travs’ Golden Era,” Arkansas Democrat-Gazette, April 16, 1996: 4C.

19 Kurosaki-Costello 2000 interview.

20 Kurosaki-Costello 2000 interview.

21 “Husker Pitching Staff May Be Tops in Big 8.”

22 California League Newsletter, 1974 (no specific date), from Ryan Kurosaki file from National Baseball Hall of Fame library.

23 Kurosaki-Costello 2000 interview.

24 “‘Year of titles’ for Panners,” Fairbanks (Alaska) Daily News-Miner, September 11, 1973: 9. Kurosaki-Costello 2019 interview.

25 “Clarinda ‘rains’ runs on befuddled Panners,” Fairbanks Daily News-Miner, June 18, 1975: 14.

26 Kurosaki-Costello 2019 interview.

27 “NU Sets Baseball Season,” Lincoln Journal Star, February 8, 1974: 25.

28 Kurosaki-Costello 2019 interview.

29 Kurosaki-Costello 2019 interview.

30 Kaneshiro, “Kalani’s Sakata, Kurosaki major achievers.”

31 California League Newsletter.

32 Kurosaki-Costello 2000 interview.

33 “Sosa Now Starter,” Tucson Daily Citizen, May 14, 1975.

34 “Clarinda ‘rains’ runs on befuddled Panners.”

35 “Clarinda ‘rains’ runs on befuddled Panners.”

36 Kurosaki-Costello 2000 interview.

37 Nakagawa.

38 Kurosaki-Costello 2019 interview. Benson’s son, pitcher Randy Benson, was Kurosaki’s teammate that year in Arkansas.

39 Kurosaki-Costello 2019 interview.

40 Regalado, 135.

41 Regalado, 132.

42 Regalado, 130.

43 “The ‘Nikkei’ path breaker with the St. Louis Cardinals.”

44 Kurosaki-Costello 2019 interview.

45 Kurosaki-Costello 2000 interview. The announced crowd that Sunday afternoon was 43,958.

46 Kurosaki-Costello 2019 interview.

47 Kurosaki-Costello 2019 interview.

48 “Does Tiant Balk?” New York Times, October 11, 1975.

49 Jed Weisberger, “Buc Clubs Pummel Redbirds, 10-4,” Indiana (Pennsylvania) Gazette, June 17, 1975: 12.

50 “Bill Valentine Retires from Arkansas Travelers,” MILB.com, March 17, 2009 (https://www.milb.com/arkansas/news/bill-valentine-retires-from-arkansas-travelers/c-525301)

51 Bailey, “Kurosaki Played Fireman During Travs’ Golden Era.”

52 “Cardinals Recall Ex-Husker Kurosaki,” Lincoln Journal Star, August 30, 1975: 10.

53 Jim Lassiter, “Kurosaki Listens for Promotion Call,” The Sporting News, July 30, 1977: 44.

54 Nakagawa.

55 Bailey, “Kurosaki Played Fireman During Travs’ Golden Era.”

56 Kaneshiro, “Kalani’s Sakata, Kurosaki major achievers.”

57 “Kurosaki Complaining,” The Sporting News, May 6, 1978: 34.

58 Kurosaki-Costello 2000 interview.

59 Kurosaki-Costello 2000 interview.

60 Kurosaki-Costello 2019 interview.

61 Kaneshiro, “Kalani’s Sakata, Kurosaki major achievers.”

62 Nakagawa.

63 Kurosaki-Costello 2000 interview.

64 Kurosaki-Costello 2000 interview.

Full Name

Ryan Yoshitomo Kurosaki http://dev.sabr.org/?p=61695

Born

July 3, 1952 at Honolulu, HI (US)

Died

, http://dev.sabr.org/?p=61695 at http://dev.sabr.org/?p=61695, http://dev.sabr.org/?p=61695 (http://dev.sabr.org/?p=61695)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.