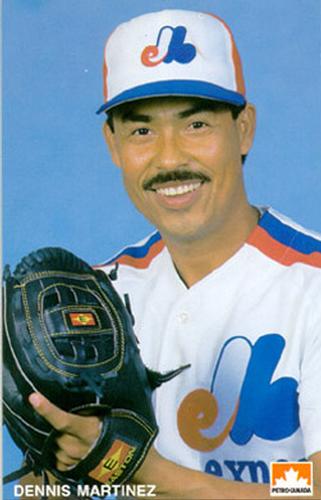

Dennis Martinez

In 1976, Dennis Martínez became the first Nicaraguan to play in the big leagues – and he remains by far the most successful. Indeed, his 245 major-league wins stood for more than 20 years as the most by any Latino pitcher, two ahead of Juan Marichal. (Bartolo Colón finally broke that record in August 2018.) Martínez got more than half of those wins after overcoming an alcohol problem that nearly derailed his career. His single most outstanding performance came on July 28, 1991, when he became the 13th pitcher to throw a perfect game.

In 1976, Dennis Martínez became the first Nicaraguan to play in the big leagues – and he remains by far the most successful. Indeed, his 245 major-league wins stood for more than 20 years as the most by any Latino pitcher, two ahead of Juan Marichal. (Bartolo Colón finally broke that record in August 2018.) Martínez got more than half of those wins after overcoming an alcohol problem that nearly derailed his career. His single most outstanding performance came on July 28, 1991, when he became the 13th pitcher to throw a perfect game.

El Presidente – as Martínez is often known in the U.S. – was a nickname he first received in 1979 from Orioles teammate Ken Singleton.1 In later years, Martínez’s name was bandied about as a candidate for president of Nicaragua, but only by a fringe party. The U.S. press ran with the idea, and it went mainstream in the States. His countrymen refer to Martínez as El Chirizo, which refers to his shock of mestizo hair. Without dispute, though, he has long been an enormous hero at home. In 1998, Nicaragua renamed its national stadium in his honor.

Denis José Martínez Ortiz was born on May 14, 1955 – or maybe 1954. Journalist Tito Rondón, who grew up in Nicaragua and is an authority on baseball there, noted that the daily La Prensa’s listing of the Nicaraguan team competing in the 1972 Amateur World Series showed 1954. Various other local press sources also show the earlier date of birth, but pending official confirmation, this biography will use 1955, in accord with Martínez’s own belief.

Rondón added, “When he signed with the Orioles, he chose the name José Dennis Martínez. As mother’s maiden name he wrote ‘Emilia,’ his mom’s first name – Emilia Ortiz de Martínez was her complete name. The Major League name became official when Dennis became an American citizen [in 1993]. When the stadium in Managua was named after him and they put up his name in lights, he insisted (and it was done) that they add the second ‘n’.”2

Martínez comes from Granada, a small city on the western shore of Lake Nicaragua and not far from the Pacific Ocean. Doña Emilia was in her forties when she gave birth to Dennis, her seventh child. He followed three brothers (Enrique, Guillermo, and Carlos) and three sisters (Lilliam, Aminta, and Adilia).3 He came ten years after his previous sibling, and this meant that he grew up a lonely child, as he told Bruce Newman of Sports Illustrated in 1991.4

What’s more, Dennis’s father, Edmundo Martínez, became estranged from Emilia while she was expecting Dennis. He too had a drinking problem. Edmundo had inherited land from his father, and Emilia ran a stall in which she sold the products that came from the farm.5 “My dad was. . .the quietest, most lovely drunk I ever saw,” Martínez told Newman. “He was very gentle. . .But when he was drinking, he would sell our pigs to get money for liquor.”6

“Emilia was a wonderful, honest, hard-working woman,” said Tito Rondón. “When Dennis reached the majors, he asked her to retire, and he kept asking her, but she never did. She always went to the market to put up her stall and sell fruit, cheeses, beef and other staples.”

In 2012, Martínez also recalled his childhood in a chat with La Prensa. “I was a rascal when I was a kid [the word he used was pícaro, the root of picaresque]. I grew up in the streets. They called me a bum, but I was a baseball bum.” He recalled using balls made of socks and that he was 13 years old when he held a real baseball for the first time. 7 In sandlot ball, however, he was a third baseman.8

According to Tito Rondón, “Dennis started to play in an organized way as an infielder in a youth league in the area between Granada, Masaya, and Jinotepe in 1971.” He also did some pitching and first attracted national attention that year when he led his team, Prego Junior, to the juvenile championship of Nicaragua. He threw a 1-0 shutout, allowing just a single infield hit and driving in the game’s only run with a homer.

Nicaragua’s first winter professional baseball league had folded in 1967, but an amateur summer league was established there in 1970. Founder Carlos García called it the First Division, and indeed it featured the nation’s best players. In 1972, Martínez stepped up to that level. The skinny 17-year-old pitched for his hometown team, the Granada Tiburones (Sharks). Tito Rondón recalled, “Before the season he tried out for San Fernando from Masaya. Their old catcher ‘Guaracha’ Castellón would say tongue in cheek, years later, ‘My claim to fame is that I fired Dennis Martínez from San Fernando.’

“Dennis then decided to try out for the Tiburones, and manager Heberto Portobanco also told him that he could not make the team. But he liked his strong arm, so he asked his brother, coach Joaquín ‘Chapuliche’ Portobanco, to take the youngster to the bullpen and teach him how to throw so they could evaluate him as a pitcher. He made the Granada team and the national squad.”

Most of the other Nicaraguan big-leaguers (12 altogether as of early 2013) also started in this league. Number two was pitcher Tony Chévez of León, whom the Orioles signed along with Martínez. Chévez was the bigger star at home, and expectations were higher for him.9 Yet after a fine early minor-league career, he pitched just four games with the 1977 Orioles. He hurt his shoulder in the fourth outing and was never the same.

That year, the Nicaraguan playoffs featured star performances from Martínez and Chévez. It was a four-team round robin that came down to a best-of-three tiebreaker between León and Granada. After Martínez won Game One on June 21, the series finished with a doubleheader on June 22 at the National Stadium in the capital city, Managua. In the opener, Chévez won 5-0 – but in the nightcap, Granada beat León with five innings from Martínez in relief.10 “You just took the ball,” said Chévez in 2009. “Everybody was watching.”11

In August 1972, the Torneo de la Amistad (Friendship Tournament) was held in Santo Domingo, Dominican Republic. Rookie Martínez surprise got a start against Cuba in a game that Nicaragua won, 5-4 – its first victory over the regional powerhouse in 20 years. 12 Later that year, the 20th Amateur World Series was held in Managua from November 15 through December 3. The hosts, Nicaragua, won the bronze medal with a 13-2 record. Martínez pitched in five games, starting two; he was 1-1, 1.86.

Less than three weeks later, on December 23, 1972, Managua suffered its devastating earthquake. That New Year’s Eve, as Roberto Clemente left for Nicaragua on his mercy mission, his plane went down off Puerto Rico, killing all on board. Martínez had come to know Clemente because Roberto had managed the Puerto Rican team in the Amateur World Series. More than 40 years later, Martínez said, “I had two idols – one as a pitcher, Juan Marichal, and the other, Clemente, as a human being. I took him as an example. He got me to think more about helping your neighbor, helping children, which was his goal and now mine too.”13

In 1973, there was a split in Nicaragua’s top amateur ranks that would last through 1977. Two leagues evolved under rival federations: the Roberto Clemente League and the Hope and Reconstruction League, or ESPERE. Martínez played for the Granada entry in ESPERE in 1973.

When he was nearly 18, on April 29, 1973, Martínez married Luz Marina García, a fellow student from Granada. “She was 15,” said Tito Rondón. “Dennis signed several months later, and left Nicaragua in March 1974. Friends told her to leave him, that in the U.S. he would forget her. But he had told her to wait for him, and she had faith in him. And in 1977, when he returned to the U.S., to the Orioles, she was with him.” They had four children: Dennis Jr., Erica, Gilberto, and Ricardo. Martínez has often credited the support of his wife in helping his life get back on track and remain there.

Owing to a conflict between international baseball organizations FIBA and FEMBA, two Amateur World Series were held in parallel in 1973. The FEMBA event took place (without Cuba) in Managua from November 22 through December 5. Following the quake, the National Stadium was in ruins and the Nicaraguan economy was still suffering. Yet the hosts still spent a precious $500,000 to stage the tourney.14

Nicaragua faced the U.S. in the gold medal game, held in León; 9,000 fans thronged the 6,000-seat stadium. The Nicaraguans had to settle for silver, though, as Martínez lost a 1-0, 10-inning duel to Rich Wortham, who pitched in four seasons in the majors (1978-80; 1983). “I heard Dennis plead with his teammates, ‘Please get me just one run, one is all I need,’” recalled Tito Rondón, who got to sit in the dugout for the first six innings. “But Wortham was much superior to the Nica hitters. Dennis had tougher foes and he tired in the 10th.”

Manager Tony Castaño told Chévez – and Martínez too, one may infer –“You gotta go north. There’s nothing for you here.”15 He tipped off his fellow Cuban, Julio Blanco Herrera, a bird dog for Baltimore.16 Regional scouting supervisor Ray Poitevint then entered the picture. He later said, “Dennis looked like a pencil. But he had natural talent, as much as anyone. And he was hungry. He wanted to be something.”17 When he was signed, Martínez weighed a mere 135 pounds.18 As a scout, though, Poitevint projected how his prospect would look when mature. Martínez filled out to 160 pounds by the time he reached Baltimore, eventually weighing 185 as a veteran. He stood 6-feet-1.

Tito Rondón and a colleague named Hans Bendixen were actually in Poitevint’s hotel room, having an engrossing conversation about scouting with Ray and Julio Blanco Herrera, when Doña Emilia arrived with Dennis. “The signing was cloak and dagger stuff,” said Rondón. “Ray and Julio asked us a favor; not to publish or talk about it.” Accounts vary as to the bonus Baltimore paid, but whether it was $10,000 or as little as $3,000, Poitevint later called it “the best money I ever spent.”19

According to Tito Rondón, keeping the signing quiet enabled Martínez to play for Granada at the beginning of the 1974 Nicaraguan season. At that time, he was also an engineering student at La Universidad Nacional Autónoma – he had a good mind for mathematics. He went there for just the first year, though, before going to the United States – Doña Emilia was not best pleased that he quit school.20

In March 1974, Dennis and Tony started their pro careers with Miami in the Florida State League (Class A). They had traveled the world before with the national team and had pitched in big stadiums, so they were not overwhelmed. Martínez ascended rapidly through the Baltimore system. In his first year with Miami, he was 15-6 with a 2.06 ERA. He struck out 162 men and allowed just four homers in 179 innings. He started the 1975 season with Miami again, but after going 12-4, 2.61, he was promoted to Double-A Asheville. He finished the season with two games at Triple-A Rochester.

Martínez pitched strongly again at Rochester in 1976 (14-8, 2.50). There were warning signs – “Unnamed teammates stated that the pitcher had developed ‘bad night-time habits,’ and enjoyed the party life.” Even so, he was the International League’s Pitcher of the Year, winning the Triple Crown of pitching. It was only the second time it had been done in the league’s history.21

Thus, in September the big club rewarded him with his first call to the majors. Rochester manager Joe Altobelli thought that Martínez would be a better big-league pitcher than Mark Fidrych, who was then enjoying his marvelous rookie year for the Detroit Tigers. Baltimore superscout Jim Russo agreed, saying, “We haven’t rushed Dennis, and our patience should pay off.” (Of course, the Orioles had that luxury back then, since their pitching was so deep.) Russo added, “Martínez and Fidrych have similar styles. They keep the ball down and have exceptional sinking stuff.”22

Martínez later described his repertoire to Orioles historian John Eisenberg. “My stuff was decent. I had a good curveball. My fastball was decent. My curveball made my fastball better. Everyone was aware of my curveball, so my fastball went right by them. But mostly, I had a big heart. . .It isn’t the stuff you have, it’s how you execute it. With desire, determination, that’s how I did it.”23 Looking back in 2011, he added, “As soon as I got a changeup, I blossomed.”24

Martínez’s debut came in long relief against the Tigers at Memorial Stadium on September 14, Ross Grimsley and Dave Pagan gave up seven runs between them in the first four innings. The rookie entered and struck out the first three batters he faced. He didn’t allow a run the rest of the way either, and he got the win because the Orioles scored four in the bottom of the seventh. After that he started three times, losing two of them, including a 1-0 decision to Boston at Fenway Park in the second-last game of the season.

As part of his development, that winter Martínez went to play in Puerto Rico with the Caguas Criollos. Thomas Van Hyning, who has chronicled Puerto Rico’s winter league in two books, wrote, “Martínez was part of the Baltimore-Caguas axis between 1976-77 and 1980-81. During this period he helped Caguas win three titles.” Van Hyning added, “Puerto Rico was a second home to Martínez. . .the quality of play appealed to [him], and he gave it his all, including the 1978-79 championship game when he bested Mayagüez’s Jack Morris.”25

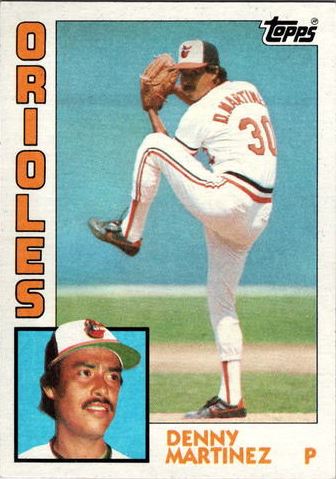

Wayne Garland, who won 20 games for Baltimore in 1976, signed as a free agent with the Cleveland Indians. Martínez therefore had a good chance to crack the starting rotation in 1977. Instead, he wound up as a swingman, starting 13 games in 42 appearances. He was 14-7, though his ERA was 4.10. In those days, four-man rotations were still the norm; Jim Palmer, Rudy May, Grimsley, and Mike Flanagan – who won the #4 starter job – started 143 games among them that year, completing 59. Manager Earl Weaver “was inclined to go with Martínez and Scott McGregor when he had to make a call on the bullpen. . .mainly because both rookies have displayed an ability to get the ball over the plate.”26

Martínez entered Baltimore’s rotation in 1978, along with McGregor. In December 1977, May had been traded to the Montreal Expos, and later the same month, Grimsley signed with the same club as a free agent. Martínez was 16-11, 3.52 in 40 games (38 starts). He had a poor first half, but at the All-Star break, pitching coach Ray Miller asked Dennis’s wife what Martínez was doing differently that he hadn’t done in the minors. Luz Marina replied that he was dipping his shoulder.27 He also addressed how he was tipping his pitches with facial expressions by sticking a big chaw of tobacco and bubblegum in his cheek – it became his visual trademark.28 In the second half, Martínez was 9-4, 2.30. He threw complete games in 11 of his last 14 starts, and in two of the other three games, he went 11 and 8 innings.

When Baltimore won the AL pennant in 1979, Martínez led the league in starts (39), complete games (18), and innings pitched (292 1/3). His results were so-so, though – 15-16, 3.66. After losing two of his first three starts, Martínez reeled off 10 straight wins in 14 outings from April 22 through June 20. He didn’t pitch that badly the rest of the way, but had little to show for it – he didn’t really pitch well enough to win much of the time either.

When Baltimore won the AL pennant in 1979, Martínez led the league in starts (39), complete games (18), and innings pitched (292 1/3). His results were so-so, though – 15-16, 3.66. After losing two of his first three starts, Martínez reeled off 10 straight wins in 14 outings from April 22 through June 20. He didn’t pitch that badly the rest of the way, but had little to show for it – he didn’t really pitch well enough to win much of the time either.

Some Orioles insiders, according to New York sportswriter Dick Young, cited Martínez’s insistence that Dave Skaggs catch him rather than Rick Dempsey.29 Skaggs joked, “When I die, they’re going to bury me 60 feet, six inches away from Dennis Martínez.”30 Martínez told John Eisenberg, “I had a lot of disagreements with Dempsey. Whatever I was doing, it wasn’t good enough or I wasn’t doing things the right way.”31 Dempsey too acknowledged the battle and the two-way frustrations, but he said, “Earl made sure I knew what he wanted us to do with each hitter. I know Dennis didn’t like it, but we won that way.”32

At least at some level, worries about his family back in Nicaragua may have been a factor too. The Sandinista revolution was in full swing, and amid the civil war, Martínez could not reach Doña Emilia by telephone. Dictator Anastasio Somoza Debayle resigned on July 17. It was soon thereafter that Ken Singleton said, “You’re going to be El Presidente,” and the name stuck.

In the postseason, Martínez started Game Three of the AL Championship Series versus the California Angels. At Anaheim Stadium, he took a 3-2 lead into the ninth inning, but after Rod Carew’s one-out double, Weaver called for Don Stanhouse, who couldn’t hold the lead.

Martínez appeared twice in the World Series against the Pittsburgh Pirates. He started Game Four at Three Rivers Stadium, got knocked out of the box in the second inning – but the Orioles’ six-run rally in the eighth inning got him off the hook. In Game Seven, he was the fifth pitcher that Weaver used in the ninth inning, when the Pirates scored two crucial insurance runs. Dennis came on with the bases loaded and hit Bill Robinson with a pitch, but then got Willie Stargell to hit into a double play.

The 1980 season was a setback for Martínez. A sore shoulder kept him out of action for most of two months from mid-May through mid-July. He was able to pitch only 99 2/3 innings, with 12 starts in 25 appearances. Bullpen coach Elrod Hendricks made an interesting observation – Martínez had not played winter ball in the 1979-80 season. “A lot of Latin pitchers cannot go without pitching in the winter,” Ellie said. “They simply develop their arms a different way.”33

Trade rumors circulated around Martínez after that off year, but his market value was low, and it turned out to be better for them that he stayed. El Presidente bounced back nicely in the strike season of 1981 – his 14 wins led the AL, and he lost just five while posting a 3.32 ERA. He came in fifth in the voting for the Cy Young Award. General Manager Hank Peters said that June, “We didn’t want to break up our pitching staff and we’ve always felt Dennis had the arm and the ability. It was just a matter of him putting it all together.”34

Martínez signed a five-year contract with Baltimore after the ’81 season. He was a workhorse again in 1982, starting 39 games and going 16-12. However, his ERA was on the high side at 4.21. That September, he had to return to Nicaragua for the funeral of his father.35 “He was walking and a truck hit him and killed him in Granada,” Martínez recalled in 1985, suspecting that alcohol was likely a factor. 36 Despite Edmundo’s grave alcoholism, Dennis still loved his father greatly – though he later regretted drinking together with him when he went back home.37

The year 1983 was when Martínez’s personal problems came to a head. It was reflected in his performance on the mound – 7-16, with a career-high ERA of 5.53. The Orioles did not use him in either the AL Championship Series against the Chicago White Sox or the World Series against the Philadelphia Phillies. Nonetheless, Martínez is still proud of his championship ring from ’83, even though he thought the ’79 squad was more talented. “This was the year I got help for my alcohol problem,” he said in 2002. “It was a bad year, but I got a new start.”38

After Martínez was arrested for drunk driving in December 1983, the Orioles staged an intervention. He entered rehab in Baltimore’s Sheppard Pratt Hospital. He told UPI sportswriter Milton Richman that he was still in denial at first, but then his counselor encouraged Martínez to find strength in prayer. “That,” he told Richman, “was the turning point of my life.”39 He stayed in control with the ongoing help of Alcoholics Anonymous meetings.40

It took more than three years for Martínez to re-emerge as an effective pitcher, though. He was 6-9, 5.02 in 1984. “I was happy to see the improvement in my mental problem,” he told Richman. “That was my prime concern. Baseball was second.”41

As part of his effort to rebound on the field, Dennis returned to Puerto Rico near the end of the 1984-85 winter season, joining the Santurce Cangrejeros.42 Martínez got another chance to be a rotation regular for Baltimore in 1985 after Mike Flanagan ruptured an Achilles tendon. He did post a 13-11 record, but his ERA remained lofty at 5.15. “Physically, he is back,” said Ray Miller that June. “Mentally, he is in the upward direction.”43

Martínez’s stock fell in 1986. He pitched just four games for Baltimore in April and then – bothered again by a sore shoulder – suffered a demotion to Rochester. In mid-June, the Orioles traded him to Montreal with a player to be named later, receiving a player to be named later in return. During the second half of the season, he started 15 games and relieved in four for the Expos, with no particular success (3-6, 4.59). He considered quitting.

After the ’86 season, Montreal refused to offer more than $250,000 to Martínez, who had been making $500,000 in the last year of his Baltimore pact.44 He became a free agent, but there were no takers, and he was barred from re-signing with the Expos until May 1, 1987. He went back to the minors again to get in shape, pitching for the independent Miami Marlins (Class A). He then re-signed with Montreal for the minimum salary. He was just 3-2, 4.46 for the Expos’ Triple-A club in Indianapolis, but when Montreal farmed out Jay Tibbs in June, Martínez got another chance.

From then on, it all came together. During six and a half seasons with the Expos, Martínez was consistently among the best pitchers in the National League. His winning percentage was good (97-66, .595), but that wasn’t all. His ERA was 2.96, including a major-league-best 2.39 in 1991. He was an NL All-Star in 1990, becoming the oldest player to make his All-Star debut, and repeated that honor in ’91 and ’92. He again received Cy Young consideration in 1991.

Along with attaining inner peace, Martínez had become a master craftsman on the mound. In 1988, he told Montreal sportswriter Ian MacDonald, “Before, when I was drinking, I used to think I was good. I didn’t think about pitching. . .I used to just try to throw the ball past the hitter. Now I think. I don’t say it makes it easy, but it makes it easier.” He moved the ball around, changed speeds, focused on the weaknesses of the hitters, and made constant adjustments, setting up batters based on their reactions from pitch to pitch.45 He also hid the ball well with his motion and threw from varied arm angles.

Many insights also come from James Buckley’s book Perfect: The Inside Story of Baseball’s Twenty Perfect Games. Ron Hassey, the catcher for Martínez’s flawless gem, said, “He had to hit his spots; he had to have his command to get guys out. But Dennis had outstanding control, and he knew how to pitch.” Center fielder Marquis Grissom said, “It was like an artist making a painting.” Opposing catcher Mike Scioscia also noted how fine Martínez’s command was, saying, “We might have played 20 innings against him and never gotten a hit.” Tito Rondón, then with La Prensa, said, “Dennis Martínez was already the most popular man in [Nicaragua] before he pitched a perfect game. Now he’s just more popular.”46

In December 1993, the 38-year-old veteran signed as a free agent with the Cleveland Indians. General manager John Hart viewed his club as a contender, and owner Richard Jacobs was willing to open up his wallet. Montreal had been paying Martínez around $3 million a year from 1991 on, but Cleveland gave him a two-year contract for $9 million. This was vast wealth by the standards of Nicaragua, where his needy countrymen already counted heavily on him.

Martínez continued to pitch well for the Indians – 32-17 (.653) with a 3.58 ERA in his three seasons there. He was particularly effective in 1995, when he made the AL All-Star team and helped Cleveland to win the pennant. In his first return to the postseason since 1979, he started once against Boston in the Division Series, getting a no-decision. He was 1-1 in the ALCS against Seattle, including seven scoreless innings in the decisive Game Six against fearsome Randy Johnson, even though his whole body hurt.47 He was 0-1 in two starts against Atlanta in the World Series.

Martínez pitched only once in 1996 after the end of July, though – elbow problems disabled him. He became a free agent again that November, and it took him until late the following February before he landed with a new team, because his elbow was perceived as too risky. The Seattle Mariners finally took a chance, and as he approached his 42rd birthday, Martínez won a spot on the roster.

He was a good influence in the clubhouse and showed initial signs that he was not done yet, but Martínez made only nine ineffective starts for the Mariners. Although his elbow held up, a surprising 29 walks in 49 innings led to a 1-5 record and 7.71 ERA. Seattle released him in May 1997. The following month, he decided to retire, citing the lack of an opportunity to keep pitching.48 He established the Dennis Martínez Foundation in 1997, with the goal of helping children, primarily in Nicaragua but also elsewhere in Latin America.

In the winter of 1997-98, however, Martínez decided to go back to Puerto Rico once more to play winter ball. As he had the previous year, he was again hoping to catch on with the Florida Marlins, since he had made his home in Miami for many years and the Nicaraguan population in south Florida was sizable. Various teams watched Martínez in his playoff showcase with the Mayagüez Indios, but Atlanta was the only one to show serious interest.49

During his 23rd and final season in the majors, Martínez was mainly a reliever, making five starts in 53 appearances. He was 4-6, 4.45 in 91 innings pitched. On June 2, he finally tied his old idol Juan Marichal for most wins in the majors by a Latino pitcher. It came with a complete-game 12-hit shutout at Milwaukee. He went ahead with a victory in relief over the Giants in San Francisco on August 9. His last win, #245, came in middle relief at Atlanta’s Turner Field on September 25. He retired all four New York Mets he faced.

Martínez got into four NLCS games for Atlanta in 1998, getting one of the Braves’ two wins against the San Diego Padres. In February 1999, he announced his final retirement, saying, “There is nothing more to do.”50

A couple of months later, the Nicaraguan Baseball Federation named Martínez coordinator of the national team for the Pan American Games, to be held in Winnipeg that July. He said that he might even join the team if it needed pitching.51 When July rolled around, he was still planning to work an inning or two in exhibition games, with an eye toward appearing against Cuba or the U.S. if Nicaragua made it as far as the semifinals. He was motivated because the Pan Am Games were an Olympic qualifying event.52 It only got as far as an exhibition appearance in Panama, though.53 A bad knee was one reason, but Mexico knocked out Nicaragua in the quarterfinals.

After retiring, Martínez worked for the Nicaraguan Visitors and Travel Bureau. He also helped coach at Westminster Christian High School in Miami. His youngest son, Ricky, was a player there. In the spring of 2005, with all his children out of school except for Ricky, he returned to the Orioles organization as a pitching instructor in camp. Old teammate Mike Flanagan, who was in the Baltimore front office, had kept in touch with him over the years about a possible return.54

Martínez spent six years (2007-12) as a minor-league pitching coach in the St. Louis Cardinals organization. He enjoyed helping many young prospects develop; among them was his son Ricky, who signed with the Cardinals as a non-drafted free agent in 2010. However, Dennis was hoping to get a shot at the big-league level.55 In November 2012, he got that chance when the Houston Astros named him as their bullpen coach.

Martínez also remained involved with the Nicaraguan baseball scene. He managed the national team in the 2011 Baseball World Cup, as well as the 2013 World Baseball Classic qualifying tournaments, held in September and November 2012. Son Ricky was part of the squad for the WBC qualifiers.

In 2004, Martínez became eligible for the Baseball Hall of Fame in Cooperstown. He received 16 votes from the Baseball Writers Association of America. That level of support meant he was “one and done” – off the ballot in 2005. Five years later, baseball author Joe Posnanski wrote, “When you add it all up he has a very similar case to Jack Morris, who is gaining Hall of Fame momentum.”56 It remains to be seen if the Veterans Committee may eventually consider Martínez. In 2011, however, he became a member of the Latino Baseball Hall of Fame in La Romana, Dominican Republic.

One may conjecture that without the lost years in the middle of his career, Dennis Martínez might be an even stronger candidate for Cooperstown. But the flip side of that argument is that his career only became what it did because of the resurrection. “I never did,” he said when asked in 2002 if he thought he would pitch for 23 years. “I think after recovery I had more of an effort to live life. And the competitor in me wanted to keep going. I did everything that God allowed me to do.

“I think the key to my longevity was staying in shape and changing my life after my addiction. Before that, I did not take good care of myself. . .But I had my family and I had a lot to play for.”57

An updated version of this biography appears in SABR’s No-Hitters book (2017), edited by Bill Nowlin.

2 E-mail from Tito Rondón to Rory Costello, March 6, 2013 (based on Rondón’s personal knowledge of the situation).

3 “Pésame a Denis Martínez por la pérdida de su madre,” La Prensa (Managua, Nicaragua), May 4, 2001.

4 Bruce Newman, “Return of the Native,” Sports Illustrated, December 30, 1991.

5 Bob Finnigan, “13 Years Of Sobriety, Dennis Martinez Has Been A Responsible Family Man, A National Hero In His Native Nicaragua And One Of Baseball’s Best Pitchers,” Seattle Times, April 25, 1997.

6 Newman, “Return of the Native”

7 Amalia del Cid, “Denis Martínez,” La Prensa, October 14, 2012.

8 Newman, “Return of the Native”; Finnigan, “13 Years Of Sobriety”

9 Hernández, Gerald. “Everth Cabrera es el décimo nicaragüense en Grandes Ligas, quiere triunfar en San Diego”. Puro Béisbol website (http://purobeisbol.com.mx/content/view/1255/1/). See also George Vecsey, “Nicaragua’s Best Pitcher,” New York Times, September 27, 1981: S3.

10 Ruiz Borge, Martín. “Asoma el tercer duelo,” El Nuevo Dia (Managua, Nicaragua), March 16, 2003.

11 Rory Costello, “Tony Chévez,” SABR BioProject (http://sabr.org/bioproj/person/94643812)

12 Edgard Tijerino, “Denis, prepárate,” El Nuevo Diario, September 18, 2011.

13 Antolín Maldonado Ríos, “Dennis Martínez fue influenciado por Clemente,” El Nuevo Día, January 4, 2013.

14 Jordan, Pat. “Dubious Triumph In Florida,” Sports Illustrated, December 9, 1974.

15 “Tony Chévez”

16 Edgard Tijerino, “¡Qué difícil fue!” La Prensa, January 13, 2003.

17 John Eisenberg, From 33rd Street to Camden Yards (New York, New York: Contemporary Books, 2001), 282.

18 Steve Henson, “The Frontiersman: Poitevint Blazes Trail for Angels as Global Scout,” Los Angeles Times, September 17, 1993.

19 Finnigan, “13 Years Of Sobriety.” The Orioles made Julio Blanco Herrera a full scout as a result of the Martínez/Chévez signing.

20 Vecsey, “Nicaragua’s Best Pitcher”

21 Brian Bennett, On a Silver Diamond: The Story of Rochester Community Baseball from 1956-1996 (Scottsville, New York: Triphammer Publishing, 1997), chapter 4.

22 “A Better Bird,” The Sporting News, September 18, 1976, 32.

23 Eisenberg, From 33rd Street to Camden Yards, 283.

24 Derrick Goold, “Dennis Martinez makes his mark as pitching instructor,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, August 14, 2011.

25 Thomas Van Hyning, Puerto Rico’s Winter League (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Co., 1995), 160.

26 Jim Henneman, “Orioles Toss Burning Problem to Fireman Drago,” The Sporting News, July 2, 1977, 18.

27 Peter May, “If Birds Ever Need a Pitching Coach…,” United Press International, September 13, 1978.

28 Newman, “Return of the Native”

29 Dick Young, Young Ideas,” The Sporting News, October 20, 1979, 20.

30 Phil Pepe, “Phil Pepe’s Patter,” The Sporting News, November 3, 1979, 16.

31 Eisenberg, From 33rd Street to Camden Yards, 305.

32 Newman, “Return of the Native”

33 Peter Gammons, “Don’t Expect Many of Those Deadline Deals,” The Sporting News, June 21, 1980.

34 Ken Nigro, “Dennis Martinez Is O’s New Ace,” The Sporting News, June 27, 1981, 15.

35 Tom Flaherty, “Orioles Serve Weaver One Last Hot Roll,” The Sporting News, October 4, 1982, 12.

36 Milton Richman, “Orioles’ Dennis Martinez Has a New Goal: Staying Sober,” United Press International, March 10, 1985.

37 Edgard Tijerino, “Era mi padre, lo quería,” El Nuevo Diario, August 28, 2011. Finnigan, “13 Years Of Sobriety”

38 Gary Washburn, “Where have you gone, Dennis Martinez?” MLB.com, September 12, 2002 (http://baltimore.orioles.mlb.com/news/article.jsp?ymd=20020912&content_id=126757&vkey=news_bal&fext=.jsp&c_id=bal)

39 Richman, “Orioles’ Dennis Martinez Has a New Goal: Staying Sober”

40 By most accounts, he stayed consistently sober, but according to one story, he had a few relapses. Ian MacDonald, “The only Montreal Expo to ever pitch a perfect game is now teaching a new generation,” Canwest News Service, March 15, 2008.

41 Richman, “Orioles’ Dennis Martinez Has a New Goal: Staying Sober”

42 Van Hyning, Puerto Rico’s Winter League, 160.

43 Jim Henneman, “Martinez’s Pitching Quiets Trade Talks,” The Sporting News, June 17, 1985, 20.

44 The Sporting News, December 22, 1986, 48.

45 Ian MacDonald, “Heeding Expos’ Call for Arms,” The Sporting News, September 12, 1988, 15.

46 James Buckley Jr., Perfect: The Inside Story of Baseball’s Twenty Perfect Games (Chicago, Illinois: Triumph Books LLC, 2012), 166, 167, 169.

47 Terry Pluto, Our Tribe (New York, NY: Simon & Schuster, 1999), 237.

48 “Dennis Martinez Retires From Baseball,” Seattle Times, June 18, 1997.

49 Mike Berardino, “Martinez Making A Brave Comeback Try,” Palm Beach Sun-Sentinel, March 8, 1998.

50 “Dennis Martinez retires,” Associated Press, February 7, 1999.

51 “Still pitching?” Seattle Times, April 19, 1999.

52 Stephen Canella and Jeff Pearlman, “Dennis Martinez’s Plans – One More Time: Pan Am Games,” Sports Illustrated, July 19, 1999. This article also confirmed that Martínez showed his year of birth as 1954 in documentation he presented for the event.

53 Dick Heller, “Coach Martinez makes pitch for himself in Pan Am Games,” Washington Times, July 12, 1999.

54 Gary Washburn, “‘El Presidente’ happy in new job,” MLB.com, February 20, 2005 (http://mlb.mlb.com/news/article.jsp?ymd=20050220&content_id=946722)

55 Goold, “Dennis Martinez makes his mark as pitching instructor”

56 Joe Posnanski, “Taking a look at the Hall of Fame ballot’s one-and-done club,” SI.com, December 2, 2009 (http://sportsillustrated.cnn.com/2009/writers/joe_posnanski/12/01/hall.of.fame/index.html)

57 Washburn, “Where have you gone, Dennis Martinez?”

Full Name

Jose Dennis Martinez Emilia

Born

May 14, 1955 at Granada, (NI)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.