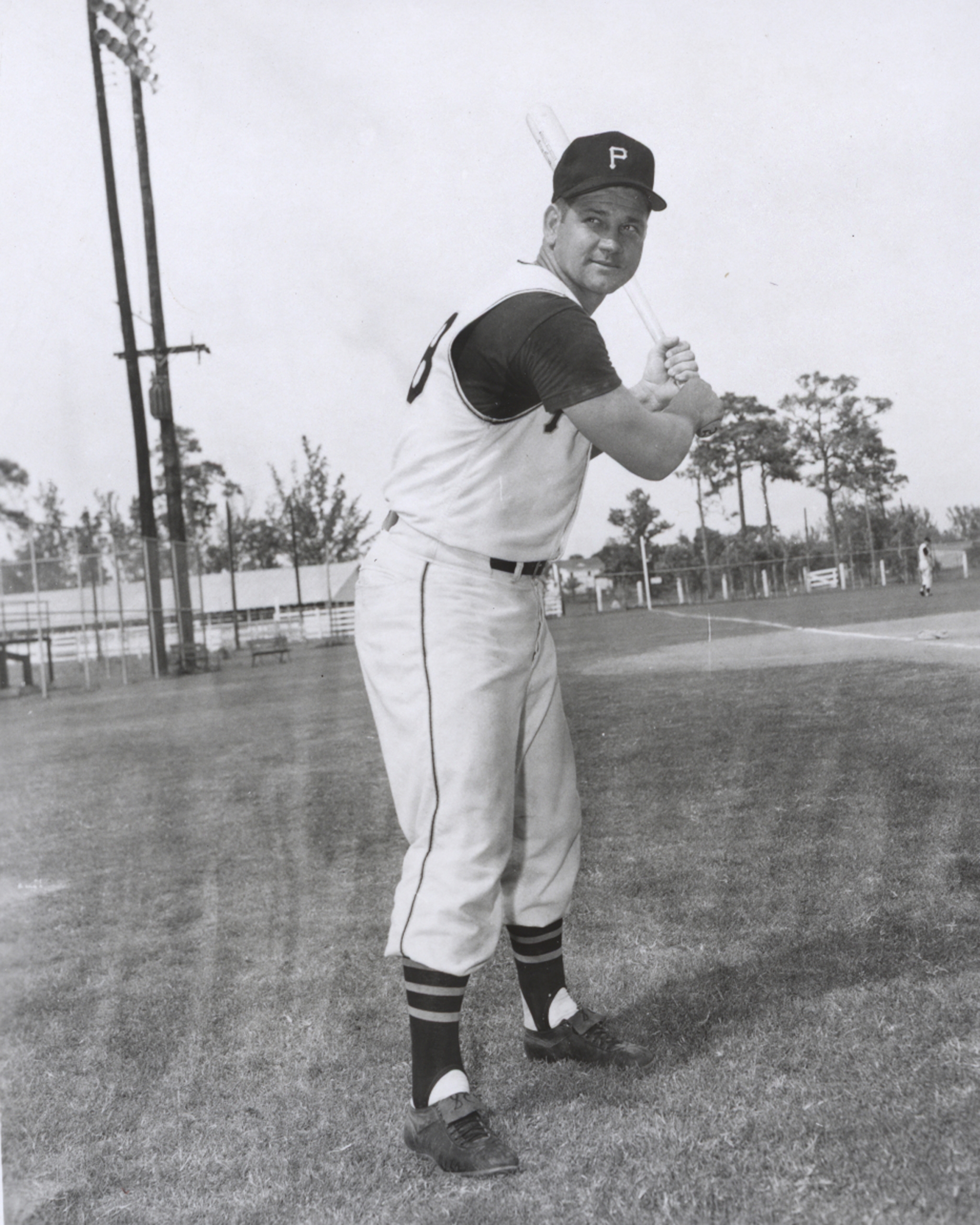

Danny Kravitz

Of the tens of thousands of people who took in the thrilling 1960 World Series at Forbes Field, Danny Kravitz might have been the only one who wasn’t completely happy to be there.

Of the tens of thousands of people who took in the thrilling 1960 World Series at Forbes Field, Danny Kravitz might have been the only one who wasn’t completely happy to be there.

His gut was a cauldron of clashing emotions – excitement, pride, envy, resentment. He had been up and down a lot of roads with those men in black and gold – with Bob Skinner in Waco, with Roy Face in New Orleans, with Bill Mazeroski in Hollywood. Not to mention five seasons playing alongside all of them in Pittsburgh. Now there they were, soaking up the spotlight while he sat and watched from afar, just another anonymous fan. They were his friends and he was happy for them, but it hurt.

Taking the long view, though, even without a World Series ring, Kravitz was living the American Dream. He had traveled a long way from meager beginnings. His parents, John Kravitz and Eva Hubiak, each immigrated to the United States from Europe and met in the bustling little town of Lopez, Pennsylvania, one of the many small industrial communities that dot the state’s heavily wooded, sparsely populated northern tier. John, a native of Russia, was a strong-backed, hard-drinking coal miner who spent three decades underground, where the toxic air clotted his lungs and turned him into an old man at a young age. His wife, an Austrian of Russian descent, was dignified and traditional, with waist-length hair wrapped into a bun and covered with a babushka. Russian was the lingua franca in their home. The smattering of English they knew they picked up from their kids, who brought it home from school.

Daniel, born December 21, 1930, was the baby of the family. Each night he and his eight siblings – all boys except for one – wedged themselves into three upstairs bedrooms, the boys two to a bed, while their parents slept downstairs in the living room. There was poor, and then there were the Kravitzes. John brought in the money; Eva stretched it to its limits and beyond. “We lived the old-fashioned way,” Danny remembered. “We used to eat dried apples; that was our candy. We raised our own vegetables, potatoes, cabbage, everything.”1 Meat came courtesy of the pigs and chickens they kept out back, while an old heifer supplied Eva with milk for homemade butter and cheese.

The kids were expected to do their share, too. They labored under a grinding regimen of chores, work, and school, which left Danny little time for baseball. But he followed the sport closely and grew especially fond of young Stan Musial, who, as it happened, was another Pennsylvania kid with Slavic roots. Years later he enjoyed greeting Musial from behind the plate in Polish. “Jak sie masz?” he would ask. (“How are you?”), to which Musial would turn and nod, “Dobre.” (“Good.”)

Kravitz participated more actively in sports as a teenager and became a standout high-school basketball player. “I was a rough guy,” he chortled mischievously. “I weighed 195 pounds and was just 6 feet but I was pretty mean on that floor.” He took up baseball at 16, pitched for his high-school team, and played all over the field on an adult team sponsored by the Weldon Pajama Factory. Even against much older players he excelled. More than once he sent a long drive splashing down into the creek that ran beyond the outfield fence.

Then after graduation, out of nowhere, the Pittsburgh Pirates called. Kravitz claimed to have no idea how the Bucs heard about him, but the next spring, in 1949, he was aboard a bus headed to a tryout camp in Greenville, Alabama, where they pinned a number to his back and put him through his paces alongside hundreds of other prospects. At first the Pirates tried Kravitz on the mound but, as he tells it, he was so nervous he could hardly throw a strike. Still, his raw talent was plain to see. “I could throw a ball through a wall, that’s how hard I could throw. And I always hit good.” The Pirates signed him for $175 a month and assigned him to their Class D affiliate in Greenville (where his teammates included a smallish, light-hitting catcher named Jack McKeon).

To John Kravitz, the whole thing made no sense at all. “Play ball?” he said to his son skeptically. “You’ve got to work!”

His son just shrugged. “They call that work, too, you know.”

Kravitz played the outfield during his first three minor-league seasons and seized the attention of the Pirate brass by hitting for both average and power, including 17 home runs and 102 RBIs in just 112 games at Class D Mayfield in 1950. But then Uncle Sam put things on hold as Kravitz spent the 1952 and ’53 seasons as a lifeguard in the Marines.

Then while on leave in 1952, he married 18-year-old Mary Jane Cole, his sweetheart from back home. When she died, they were just nine days short of their 51st wedding anniversary. Over the years she and their three children moved more than 30 times as they followed the meandering path of Danny’s itinerant career. “I took her all over the country, Puerto Rico, the Dominican. She knew baseball better than me,” he joked.

He and Jane made a fun couple in the same way that the Kramdens or the Flintstones made fun couples. Danny was genuinely good-hearted, but in private he often turned impatient and blustery, with a thundering voice that could set the walls trembling. Jane had a little more finesse, but she refused to sit quietly for his nonsense. As a result, they were always bickering about one little thing or another. It wasn’t that they were particularly angry most of the time; it’s just how they communicated. If they weren’t picking at each other, that’s when you knew something was really wrong.

After being mustered out of the service, the young husband returned to Pirate camp in the spring of 1954, whereupon Pirates general manager Branch Rickey summoned him into his office.

“Son,” Rickey bellowed. “How would you like to become a catcher?”

Kravitz knew the right answer. “I’ll play anywhere, any position. Just let me play.”

The organization was thin on left-handed-hitting catchers – or, for that matter, catchers who could hit at all. Kravitz filled that void, and with the position switch found himself with a clear path to the major leagues. A defensive wizard he was not, but he got the job done. He was adequate at throwing out baserunners and matured into a competent game-caller. He had just one peculiar flaw – according to play-by-play summaries he committed at least ten errors on dropped pop flies in just 171 major-league games behind the plate. A fan observed a tad ungraciously, “Danny Kravitz … couldn’t catch a foul popup behind home plate without a catcher’s mitt glued to the top of his head.”2

At any rate, the Pirates probably never expected a Gold Glove out of Kravitz. They just wanted him to hit, and in the minors he did plenty of that, earning a place on the Southern Association All-Star team after a stellar 1955 season in which he batted .298 with 19 home runs. Then he kept it up in camp the following spring. “I hit everything they threw at me,” he crowed. “I made those pitchers look silly.” On April 17, 1956, Kravitz started behind the plate in the Polo Grounds as the Pirates opened the season against the New York Giants. (It was a nightmare debut, though. His two errors led to two unearned runs and handed the Giants a 4-3 win.)

Kravitz popped in and out of the lineup during the first 2½ months of the 1956 season, showing only occasional glimpses of his offensive prowess. On May 11 he blasted his first major-league home run, an upper-deck grand slam in the bottom of the ninth to beat Jack Meyer and the Phillies, 6-5. As of 2016, he was one just 28 players in major-league history to record a walk-off grand slam with his team trailing by three runs. Kravitz’s teammates mobbed him at home plate, while an apoplectic Meyer stormed back to the Philadelphia dugout, snatched a bat out of the rack, and pounded a porcelain drinking fountain into shards.

The grand slam aside, Kravitz was scuffling. It seemed as though his fortunes had turned in late June, when he started three straight games, went 5-for-8 with a home run, and hiked his average from .220 to .269, but all that got him was a trip back to the minor leagues, where he remained the rest of that year and most of the 1957 season.

Things like that just seemed to happen to Kravitz. “He wasn’t the luckiest ballplayer in the world,” offered longtime teammate Bob Skinner. “He was a dangerous hitter but he never really got a chance to play every day for a period of time where he could really show his stuff.”3 Kravitz found it hard to figure. Catcher had been a revolving door for the Pirates for ten years; he was the only viable long-term solution at hand. Publicly, anyway, the Pirates brass insisted they were counting on him. Manager Bobby Bragan went so far as compare him to a young Yogi Berra, and predicted in December 1956, “If Kravitz comes through as expected and we land an additional power hitter, we’ll be a much-improved outfit next year.”4

Nonetheless, over the next few seasons Kravitz appeared only sporadically, and always on a short leash. A teammate, quoted anonymously, told the Pittsburgh Press, “He [has] a tendency to be all tightened up instead of relaxed but that’s easy to understand. You can’t expect a man to come off the bench as a sub and not be afraid that one mistake could run him back to the bench for a long spell. He’s so eager to make good he fights himself.”5 On June 21, 1959, Kravitz rapped out five hits in a game, boosting his average to .356. Five hits surely were enough to earn another start, he assumed. The following day he bounded into the clubhouse eager for a look at the lineup card – only to learn that he was back on the bench. He glowered in the dugout all afternoon, doing a slow, bitter burn. “We lost that game. Not that I was wishing we lost but it kind of tickled me to see it happen.” In July he started 12 games in a row due to an injury to starter Smoky Burgess. He batted .311 over that stretch, but inevitably returned to his backup role when Burgess got healthy again.

Kravitz was an enormously confident, fiercely proud man who took the lack of playing time almost as a personal insult. He had never really known failure on the baseball field, and in his mind he wasn’t failing in Pittsburgh either, he just wasn’t being allowed to succeed. In some ways his grievances sound like sour grapes; on the other hand, it is difficult not to empathize. All of us have walked in those shoes at one time or another, feeling we are doing everything that is asked, everything that is demanded, but there we remain, trapped in the cage. “I did the best I could [but] what they were doing to me, gee! Smoky Burgess came over. He was a good hitter but he couldn’t throw. He couldn’t run. They’d work me against the hard throwers because Smoky couldn’t hit the good fastball. Hank Foiles couldn’t hit me, but he was a good receiver.” Kravitz waited and waited but new faces kept appearing and it was always someone else’s turn.

He also longed for financial security. Toiling as a young backup catcher was not a lucrative business. “I try to save a few dollars each year on my salary but it isn’t much,” he told a reporter in 1960. “I haven’t even been able to buy my own home and I live in a small town of only 700 people.”6 In the winters he resorted to fur trapping, which proved a surprisingly profitable avocation. A mink or beaver pelt got him $25.

Socially and economically, Kravitz wasn’t far removed from the average Pirates fan. He was busting his hump to make ends meet the way many of them were. He grew up in a large, working-class, immigrant family as many of them did. So people identified with him and embraced him as almost a minor folk hero. A big, affable bear of a guy in public, completely without pretense, Kravitz moved easily among fans and genuinely enjoyed their attention. He wore his Russian Orthodox heritage proudly and became a frequent guest of the city’s many ethnic organizations. “The people liked me [in Pittsburgh],” he declared. “They were all Polish, Russian, Italians, and I fit right in with them.”

But by 1960 Kravitz clearly did not fit in with the Pirates’ plans. Recently acquired veterans Burgess and Hal Smith split all the work, reducing Kravitz to a seldom-used pinch-hitter. The inevitable came on May 31, when the Pirates traded him to the Kansas City Athletics. General manager Joe L. Brown talked as if he were doing Kravitz a favor, sending him to the American League rather than back to the minors. “Danny is a nice kid. I wanted to make sure of placing him with another major league club.”7

Kravitz saw it much differently. He was devastated, and still sounded crestfallen more than a half-century later. “I got a little shafted there,” he lamented. The deal probably shouldn’t have surprised him, but it did. “I never thought I’d be traded out of Pittsburgh. I never did. The fans hated to see me leave, but that’s baseball, I guess.”

The other thing about the trade to Kansas City – it was Kansas City. “It was just a lousy club. They were in last place all the time. It wasn’t easy for me to go over there because I was used to playing on a winner.” The Athletics finally gave him a chance to play regularly, but he didn’t make much of the opportunity, batting just .234 in 59 games. And while his new team was pushing 100 losses, Pittsburgh was winning the World Series. “It really shook me up. I was so close to getting one of those nice rings, but I got nothing.” His buddies on the Pirates did award him $250 out of their Series winnings, but that did little to salve the wound. “I was happy they won, but it sure shocked me what [management] did to me.”

Over the next three years Kravitz bounced from organization to organization but never made it back to the big leagues. He retired after the 1963 season and returned to Dushore, Pennsylvania, just a few miles down the road from his hometown. As time went on, Jane, at least, began to feel cramped and wondered whether they had made the right decision. “There was some talk that he shouldn’t have come back home, that he should have stayed in Pittsburgh. He could have gotten a job with the organization,” according to Kravitz’s daughter, Pam. “I think they got so tired of moving that home was a welcome sight, but then that got old, too. I think she regretted that they came back to that little mining community.”8

But theirs was a good life in many ways. Danny and Jane purchased ten acres and built a lovely house with an outsized pond in the back yard, which their friend Joan Skinner thought was as peaceful as a place could be. “My favorite thing was to sit on the dock and listen to the bullfrogs,” she said wistfully.9 He spent 23 years as an inspector for the electronics firm Sylvania while Jane operated a hair salon out of their basement. Together, they usually scraped together enough money for an annual vacation to the Jersey Shore. Danny drove to Pittsburgh for reunions of the 1960 Pirates team and got together often with former teammates Bob Skinner and Bill Mazeroski.

In the early 2000s Kravitz endured a crushing series of personal tragedies. In a nine-month span he lost two brothers, his 42-year-old son Danny, who collapsed and died of a heart attack right in front of his dad, and then his beloved Jane, who seemed to lose her will to live after her son’s death. And then the years finally began to catch up to him as he entered his 80s. His legs and hands gave him trouble and his heart became an ongoing concern. But he still managed to keep pace with his teenage grandsons, cheering (sometimes a little too loudly) at their baseball games and taking them into the woods to hunt and fish. He was the kind of grandfather the typical teenage boy would love – a colorful, charmingly gruff old goat with a fondness for sports and guns. In return, his grandkids helped keep him young. “They come here and ride my four-wheeler to hell and back. We have a lot of fun together.”

Kravitz died on June 19, 2013, at the age of 82 in Danville, Pennsylvania.

Even though Kravitz is merely a footnote in Pirates history, he remained prominent in Sullivan County, Pennsylvania. A half-century after he walked away from baseball, people still asked him to speak at banquets and sign autographs. “Everybody likes me around here. They know me when they see me and they respect me.” To people in town, Danny Kravitz was not the poor guy who got robbed of a World Series ring or the frustrated slugger who never got a real shot. Instead, he was someone to look up to, someone who made it.

This biography is included in the book “Sweet ’60: The 1960 Pittsburgh Pirates” (SABR, 2013), edited by Clifton Blue Parker and Bill Nowlin. For more information or to purchase the book in e-book or paperback form, click here.

Sources

Richard Peterson, The Pirates Reader (Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press), 2003.

Baseball Digest, October 1978.

Pittsburgh Post-Gazette and Sun-Telegraph; June 3, 1960.

Pittsburgh Press, April 4, 1956; March 10, 1960.

The Sporting News, May 2, 1956; December 19, 1956; November 2, 1960.

Sullivan (Pennsylvania) Review; July 27, 2006; November 10, 2010.

Retrosheet.org.

National Baseball Hall of Fame player file, undated articles.

1920 United States Census.

Danny Kravitz, telephone interview with author, October 4, 2011.

Pamela Kravitz-Arthur, telephone interview with author, October 9, 2011.

Bob Skinner, telephone interview with author, October 17, 2011.

Joan Skinner, telephone interview with author, October 17, 2011.

Lenny Yochim, telephone interview with author, October 11, 2011.

Notes

1 All quotations are from an October 4, 2011, interview with Danny Kravitz, except as noted.

2 Richard Peterson, The Pirates Reader (Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press, 2003), 6.

3 Bob Skinner, telephone interview with author, October 17, 2011.

4 The Sporting News, December 19, 1956.

5 Pittsburgh Press, March 10, 1960.

6 Ibid.

7 Pittsburgh Post-Gazette and Sun-Telegraph, June 3, 1960.

8 Pamela Kravitz-Arthur, telephone interview with author, October 9, 2011.

9 Joan Skinner, telephone interview with author, October 17, 2011.

Full Name

Daniel Kravitz

Born

December 21, 1930 at Lopez, PA (US)

Died

June 19, 2013 at Danville, PA (US)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.