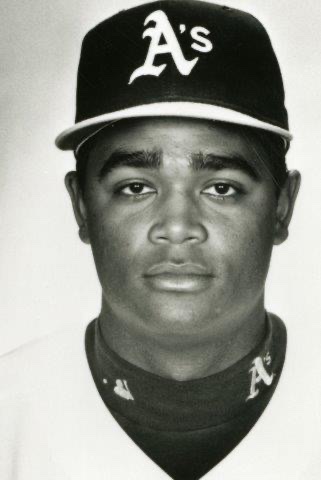

Tony Batista

A picture of Tony Batista at the plate perhaps deserves some recognition in a corner of Cooperstown. When the right-handed batter came to plate, he had an open stance that caused his chest to face the pitcher. His left leg was nearly even with his right leg. His hands were at eye level with the bat. As the pitcher wound up, Tony brought his open left leg in and closed his stance, back to a natural baseball “open stance.” This stance made him pull the ball to left field, hit for more power, help him stay in the major leagues and promote one of his passions, Christian missionary work, throughout his professional baseball career.

A picture of Tony Batista at the plate perhaps deserves some recognition in a corner of Cooperstown. When the right-handed batter came to plate, he had an open stance that caused his chest to face the pitcher. His left leg was nearly even with his right leg. His hands were at eye level with the bat. As the pitcher wound up, Tony brought his open left leg in and closed his stance, back to a natural baseball “open stance.” This stance made him pull the ball to left field, hit for more power, help him stay in the major leagues and promote one of his passions, Christian missionary work, throughout his professional baseball career.

Batista’s batting stance was so extreme that the Batting Stance Guy, Gar Ryness, blew out his back imitating it stance for his book, Batting Stance Guy: A Love Letter to Baseball. Ryness wrote, “He stands with his front foot planted in the far back corner of the box, body facing the pitcher, bat in the clouds. If a kid in T-ball did that, any self-respecting coach would be on him in a flash, rearranging just about everything.”1

But that stance aided Batista during 11 major-league seasons spread among six teams, and one season in the Japanese Pacific League. Helped him make two All-Star Game appearances, and hit 221 career home runs. Batista split duties at third base, second base, shortstop, and DH; 807 out of his 1,188 games were played at third.

Leocadio Francisco Batista Hernandez was born on December 9, 1973, in Puerto Plata, Dominican Republic. According to Miguel Tejada, a friend, Batista’s parents lived in Mao Valverde Province in the Dominican Republic. Their occupation was raising animals like goats, pigs, and cattle.2

Batista graduated from Liceo Juan de Jesus high school. He became interested in baseball by watching his two older brothers, Ramirez and Vicente, who eventually turned pro, play the game. “I learned from them, they both were professional players in the states but they only got to Double A,” he said.3

In 1991, at the age of 17, Batista signed with the Oakland Athletics out of high school. His best season in the minors was 1994 for the Modesto A’s in the Class-A California League, when he slugged 17 home runs and hit .281/.359/.459 in 119 games. In 1996, batting .322 for Triple-A Edmonton (Pacific Coast League), the 22-year-old Batista earned a call-up to the Athletics on June 3. In his major-league debut that night, Batista, playing third base and batting ninth, went 0-for-3 against Kansas City’s Kevin Appier with two strikeouts. In 1996 and 1997, he bounced back and forth between Edmonton and Oakland.

Batista played some shortstop for the A’s, but was dogged by his poor defensive play at the position, and in 1997 Miguel Tejada took over the position. After the season Batista was unprotected by Oakland and was taken in the expansion draft by the Arizona Diamondbacks as the 27th pick. Meanwhile, Batista, mired in a 0-for-28 hitless streak in the Dominican winter league, adopted his wide-open left-footed stance. He said he didn’t know why he chose such a bizarre, unique stance. “I tried to do something different,” he said. “And right away I got a hit with that kind of stance and it’s been working for me since that day.”4

The new stance gave him consistent major-league home run power. Batista slugged 18 home runs for the Diamondbacks in 1998. Defensively, he bounced between third base, shortstop, and second base in 106 games. He didn’t settle into a full-time role and hit .273 with those 18 home runs. In 1999 he settled in at shortstop, playing in 44 games (.257, 5 home runs) for the Diamondbacks. On June 11 he was traded to the Toronto Blue Jays with right-handed pitcher John Frascatore for left-handed pitcher Dan Plesac. In 98 games for the Blue Jays he batted .285 with 26 homers.

With Toronto for the full 2000 season, Batista posted his best season, batting .263 with 41 home runs and 114 runs batted in. This earned Batista his first of two All-Star Game appearances. But in 2001 he regressed. Batting just .207 with 13 home runs in 72 games, Batista was sent to the Baltimore Orioles on waivers. This was Batista’s fourth big-league club in just five seasons. For the Orioles the rest of the season, Batista batted .266 with 12 home runs.

Batista played in 161 games for the Orioles in 2002, batted .244 with 31 homers, and earned his second All-Star Game selection.

In 2003 Batista again played in 161 games. His production fell off slightly: .235, with 26 home runs. After the season he opted for free agency. He signed with the Montreal Expos for one year at $1.5 million. The Expos became his fifth big-league team in seven major-league seasons. For the Expos he batted .241, slugged 32 home runs and drove in 110 runs, seventh highest in the National League.

Hitting 89 home runs and driving in 296 runs over three seasons should have been enough for Batista to earn another major-league contract. Tampa Bay, Detroit, and Houston reportedly offered him deals. But none came close to the two-year, $15 million contract he signed with the Fukuoka Daiei Hawks of the Japan Pacific League. The deal also included a $5 million signing bonus. The Hawks, were looking to splurge on a young major-league talent, offered him well over the $1.5 million the Expos had paid him. Batista, now 31 years old, took the offer and crossed the Pacific to play Japanese baseball.

In Japan Batista played in 135 out of the season’s 136 games, batted .263, and hit 27 home runs. Perhaps this should have been enough for him to deserve another shot in the JPL. But it was not to be. Possibly Batista was too laid-back in Japan and seemed lackadaisical. Perhaps, it was the adjustment to Japanese culture. He had some unusual behavior on the field in Japan. See, for instance, a video that turns up in a web search of “Tony Batista scares pitcher.”5 One Japanese beat writer dubbed Batista “Mr. Nonchalant.”6 But most likely it was the fact he was the highest-paid player on the team but didn’t produce the highest numbers. Although Batista finished a league leader in several statistical categories, apparently his numbers didn’t justify his salary and the Hawks wanted younger talent. Batista was 31. Rather than pay another $15 million, the Hawks bought out his contract for $4.5 million.

Two days after getting his release, on December 15, 2005, Batista inked another deal to return to the United States with a one-year, $1.25 million contract with the Minnesota Twins. His bat was expected to fill a power void in the Twins lineup and he would serve in a needed role at third base and designated hitter.

The Twins’ hopes were not met. In 50 games, Batista batted just .236 with 5 home runs, and was released on June 14. Twins manager Ron Gardenhire said, “If you are not going to hit home runs, then you’ve got to be able to run. We were hoping that Tony would hit a few more home runs.”7

Batista played winter ball in the Dominican Republic in the 2006-2007 season for the first time in the eight years since he adopted his trademark batting stance. Batista needed the winter league to help market himself for another big-league contract at the age of 32. He batted only .213 in 18 games, and signed a minor-league deal with the Washington Nationals with an invitation to spring training. Batista made the 2007 Nationals roster in spring training but had little power impact, hitting only two home runs in 80 games.

At the age of 34, Batista returned to play 16 games in the Dominican Winter League and again landed a minor-league deal with the Nationals. This time he didn’t make the major-league, and played only 17 games at Triple-A Columbus. He played winter ball again, but was unable to attract even a minor-league contract.

According to Baseball-Reference.com, Batista made just shy of $40 million playing in the major leagues and Japan. He donated a large portion of his salary to charities and churches and saw himself as a Christian missionary.

When his team played on the road, Batista made it a practice to donate to local churches. He once asked his Kansas City taxi driver to take him to any church. The driver randomly selected Country Club Christian Church, where Batista asked to see the minister. The minster was tired after that Monday after officiating at three weddings and preaching three times the weekend before. Batista instructed her to open the Bible and turn to Malachi 3:10: “Bring ye all the tithes into the storehouse, that there may be meat in mine house, and prove me now herewith salt the Lord of Hosts. If I will not open you the windows of heaven, and pour you out a blessing, that there shall not be room enough to receive it.” Batista then spoke a little bit in broken English and said, “I am convinced of this.” He gave her a thick white envelope with the Fairmont Hotel logo. Batista left and said something about the taxicab still waiting outside. Inside the envelope was $16,400. The church finance director said later, “It revives your faith in people. I still think players are paid too much but there are ones who are blessed.”8

Batista said to a reporter in 2006, “God uses me. Everywhere I go I talk about Him and the power he has.” Batista was almost always available before and after game for an autograph.9 But the memory of that awkward wide-open stance remains in the hearts of baseball fans.

Last revised: October 29, 2022

Sources

The author consulted Tony Batista’s player file at the National Baseball Hall of Fame Library, and relied upon baseball-reference.com.

Notes

1 Gar Ryness and Dewart Caleb, Batting Stance Guy: A Love Letter to Baseball (New York: Simon and Schuster, 2010), 36-41.

2 Miguel Tejada, email correspondence with Julio Rodriguez, July 23, 2018.

3 Steve Riach, Life Lessons From Baseball (Colorado Springs: Honor Books, 2004), 13-17.

4 Riach.

5 “Throwback Sports Clip Of The Week: Tony Batista Scares The Hell Out Of Asian Pitcher!,” YouTube.com, December 2, 2011. youtube.com/watch?v=lUiQlPzcm44.

6 Wayne Graczyk, “Batista’s Number Didn’t Justify His Massive Salary,” Japan Times, December 18, 2005.

7 Jayson Williams, “Line Up Redo Puts Batista out, Bartlett In,” St. Paul Pioneer Press, June 24, 2006.

8 Joe Capozzi, “Batista’s Gift to Church Exemplifies Generosity,” Cleveland Plain Dealer, August 5, 2002.

9 Jonathan Weeks, Latino Stars in Major League Baseball: From Bobby Abreu to Carlos Zambrano (New York: Rowman and Littlefield, 2017), 6-8.

Full Name

Leocadio Francisco Batista

Born

December 9, 1973 at Puerto Plata, Puerto Plata (D.R.)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.