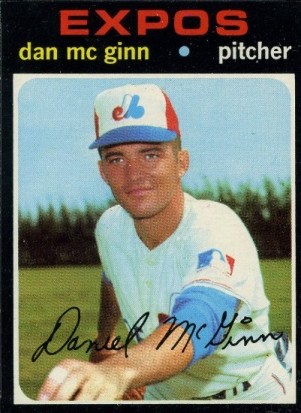

Dan McGinn

“The Shooting of Dan McGrew” is a famous poem written by Robert W. Service in 1907 about two men who end up shooting each other in a bar during the Yukon gold rush. The title character, one of the victims, was known as Dangerous Dan.

“The Shooting of Dan McGrew” is a famous poem written by Robert W. Service in 1907 about two men who end up shooting each other in a bar during the Yukon gold rush. The title character, one of the victims, was known as Dangerous Dan.

McGrew may have been Canada’s first Dangerous Dan, but he wasn’t the only one. Dan McGinn, who got his nickname for being more dangerous with a football than with a gun (more on that later), pitched for the Montreal Expos from 1969 to 1971, and had brief stints with the Cincinnati Reds (1968) and the Chicago Cubs (1972).

Daniel Michael McGinn was born in Omaha, Nebraska, on November 29, 1943, the eldest of three children born to Gerald and Elizabeth McGinn. Dan was a boy of his time, getting involved in baseball at a time when 5- and 6-year-olds faced actual pitching instead of hitting a ball off a tee.

“We never had anything like T-ball,” said McGinn. “We always played actual baseball. Sometimes it ended up the coach having to pitch because none of us could throw a strike or throw it up where they could hit it.”1

McGinn was a multisport athlete at Omaha Cathedral High School, in football, baseball, and basketball. Although he excelled at all three sports, McGinn said that he almost had no choice about which sports to play.

“I went to a small Catholic high school,” he said. “And it was almost mandatory that if you were a halfway decent athlete, you had to play all three sports.”

McGinn was far more than a “halfway decent athlete.” In 1962 he quarterbacked the football team and led the North squad in the Nebraska high school Shrine football game to a 28-0 victory, winning the outstanding-player award. His appearance in that game increased his profile with big-time college football programs. He had already signed a letter of intent to play for Nebraska under legendary coach Bob Devaney, but was invited to visit Notre Dame after the Shrine game. McGinn fell under the spell of Touchdown Jesus and became a member of the Fighting Irish. Devaney was not pleased.

“I think McGinn has made a mistake,” Devaney said. “We play his type of football, Notre Dame doesn’t” – meaning that Nebraska’s offense was geared more to running quarterbacks while Notre Dame’s was suited more to pocket passers.2

It’s impossible to say whether Devaney was correct, but McGinn’s career passing statistics at Notre Dame included five completions in six attempts for 65 yards over three seasons.3 His playing time was limited for the first two of those years because he played behind John Huarte, who won the Heisman Trophy in 1964. Having that caliber of player ahead of him forced McGinn to become like Gypsy Rose Lee and be very versatile. During his football career he played quarterback, punter, split end, running back, and defensive back. That’s not to say he was a Dan of all trades and master of none. It was his punting prowess during a dreadful 2-7 Irish campaign in 1963 that gave him his “Dangerous” nickname.

“McGinn, the team’s punter came in against Purdue and was forced to chase an errant snap pursued by half a ton of Boilermaker beef,” wrote Cappy Gagnon in his book on great Notre Dame baseball players. “While on the run, the athletic McGinn got off a 50-yard soccer-style boot. In a subsequent game, he completed a first-down pass in similar circumstances; thus a nickname was born: Dangerous Dan.”4

McGinn was a good enough punter that he achieved a rarity of sorts, when he got to play in his second Shrine game, again for the North, as a college senior. His second go-round wasn’t quite as fortunate – the South squad blocked one of his punts and eventually scored a touchdown.

When not kicking footballs for Notre Dame, McGinn was on the mound for the baseball team as a starting pitcher. According to longtime Irish baseball coach Jake Kline, Dangerous Dan lived up to his nickname even on the baseball team when the squad had to practice indoors during inclement weather.

“Jake Kline recalled that there was another place where the left handed McGinn was a danger,” wrote Gagnon. “Each year, before the temperatures in South Bend permitted the Notre Dame baseball team to practice outdoors, they would spend weeks warming up in the old Field House. Jake said that catchers were always scarce when McGinn needed warming up. In that dimly lighted old building, Dan’s 90-plus mile per hour fastball and uncertain control presented quite a challenge to the backstops.”5

Any roughness around the edges got smoothed out by McGinn’s junior year in 1965. Although he had a 5-6 record with a 5.42 ERA, he struck out 105 batters in 74? innings. In fact, as of 2014 he still held the school record for strikeouts per nine innings (12.66).6 Those numbers impressed the St. Louis Cardinals, who drafted him in the 21st round of the first-ever amateur draft, but Dan chose not to sign with them.

“They said, ‘We want to send you to Class A Rockville, South Carolina,’ and I said no, I think I’ll go back for my senior year and play football.”

McGinn pitched in the Illinois Collegiate League that summer, then played his final season of collegiate football. In January 1966 the Cincinnati Reds chose him in the first round of baseball’s secondary draft. This time he signed, with the understanding that he would complete his degree. (Signing the contract made him ineligible to play collegiate baseball.) He attended spring training with the Reds, then returned to school to become what was a rarity among ballplayers in those days, a college graduate, with a bachelor’s degree in communication arts. He graduated on June 10, 1966, and on June 12 reported to the Knoxville Smokies of the Double-A Southern League.

McGinn’s first two years in the minors, both as a starter with Knoxville, were a struggle; he went 2-1 with a 5.23 ERA in 1966 and 6-13 with a 3.49 ERA in 1967. He found his stride in 1968, when the Reds’ Double-A franchise was the Asheville (North Carolina) Tourists, also of the Southern League. The Tourists won the league championship. The Reds converted him from a starter to a reliever that year; he pitched in 74 games, with only three starts. He compiled a 6-3 record, a 2.29 ERA, and 133 strikeouts in 110 innings, and made the All-Star team.

“Sparky Anderson [was] my manager and at the beginning of the year he said to me that Cincinnati is loaded with left-handed starters, but they need a left-handed reliever, so let’s make you a reliever,” Dan recalled.

McGinn’s stats prompted the Reds to call him up on September 3, and that night he made a rather unique major-league debut against the eventual league champion Cardinals, coming in as a pinch-runner in the bottom of the 10th inning. He took the mound to start the 11th and walked the first major-league batter he faced, pinch-hitter Ed Spiezio. The next batter was Lou Brock; McGinn got behind in the count and was replaced on the mound by Billy McCool, who eventually completed the walk. Both runners came around to score, allowing the Cardinals to win, 5-3. McGinn was tagged with the loss. His tough outing may be explained by the fact that he showed up at Cincinnti’s old Crosley Field without a map.

“I get there late because I had to fly up from Asheville. I get to the park and the game has already started. I don’t know anything about Crosley Field. Mel Harder, the pitching coach, says, ‘Go on down to the bullpen.’ The bullpen was tucked behind the left-field line. I’m looking around like, ‘Where the hell’s the bullpen?’”

What happened next sounded like the script from the movie Bull Durham.

“So I go wandering down to the bullpen,” McGinn continued. “All of a sudden the phone rings and they tell Ted Abernathy and myself to warm up. We warmed up, and all of a sudden I get called out to the dugout. And (manager Dave) Bristol says, ‘Go pinch-run for Maloney [it was actually Don Pavletich].’ I said, ‘Do what? Go pinch-run? Well, okay. I don’t know the signs or anything.’ He said, ‘Don’t worry, the first-base coach will tell you.’ So I go over to first base. … There’s a pop-up and the inning is over with. I start running over to the dugout and Bristol says, ‘You’re in there!’ I said, ‘To pitch?’ He said, ‘Yeah.”

McGinn got into 14 games with the Reds that year, going 0-1 with a 5.25 ERA. One game against Pittsburgh stood out in his mind because he came in with two on, one out, and slugger Willie Stargell coming up. Catcher Johnny Bench came to the mound, smiled, and simply said, “You’re in trouble, pal,” then went back behind the plate. Dan got out of trouble by striking out Stargell and Donn Clendenon.

After the 1968 season ended, teams had to prepare for the expansion draft that allowed the four new clubs, the Montreal Expos, San Diego Padres, Kansas City Royals, and Seattle Pilots, to stock their rosters.7 The Reds left McGinn unprotected and the Expos made him their 14th pick. McGinn was on the major-league roster when the season started, and he decided to wait until the team’s first game, on April 8, 1969, to have an impact.

Jim “Mudcat” Grant was the Expos’ starter in their first-ever game, against the New York Mets at Shea Stadium. It was clear early that Grant didn’t have it that day, so Expos manager Gene Mauch brought McGinn in during the second inning. Dan not only became the first Expos relief pitcher, but the first one to pick off a baserunner, when he nailed Mets center fielder Tommie Agee at second.

“It was a play we had worked on in spring training and [shortstop Maury Wills] put on the sign,” recalled McGinn. “I just did what I had been taught to do. We caught (Agee); I don’t think he had any idea we would be using a pickoff. He wasn’t really paying enough attention.”8

In the fourth, McGinn added to his list of firsts, becoming the first Expo, pitcher or not, to hit a home run – off Tom Seaver no less – a solo shot that bounced off and over the outfield wall and put the Expos up 4-3. It was his first major-league hit and his only career home run at any professional level.

“(Seaver) threw a fastball and I just happened to make a good swing and he supplied all the power,” said McGinn. “I was rounding first and [first-base umpire Stan Landes] gave the home-run signal. In the dugout Rusty and Maury and Gene were all just standing there laughing as I went in. If you’re going to hit one you might as well hit it off a Hall of Famer.”9

The Expos won that game 11-10, but McGinn wasn’t involved in the decision. He had to leave the United States to capture his first major league W. This happened on April 14, 1969, in the Expos’ inaugural home opener at Jarry Park. Larry Jaster started for the Expos and cruised through the first three innings as the Expos built up a 6-0 lead. Five errors in the fourth along with a grand slam by light-hitting shortstop Julian Javier led to seven Cardinals runs, only two of which were earned. McGinn replaced Jaster with two out in the inning. Dan went the rest of the way, and even drove in the winning run in the seventh inning, as the Expos won 8-7. That victory was the highlight of McGinn’s season, and not just because he pitched 5? scoreless innings, allowing three hits and walking one.

“At the time (getting the game-winning hit) was more fun for me,” said McGinn.

McGinn went on to have a pretty good season in 1969, appearing in 74 games (all but one in relief). He compiled a 7-10 record with a 3.94 ERA and six saves, which were pretty good numbers on a team that went 52-110. He also got the opportunity to live in Montreal in the offseason, workingas a public-relations representative for Seagram’s Distillery, which was owned by Expos managing partner Charles Bronfman. He, along with teammate Steve Renko, would sign autographs at liquor-store openings and visit major customers with Seagram’s sales representatives. He loved living in Montreal, except for the taxes and the snow.

“I’m from Nebraska where it snows, but not like that,” McGinn said. “As a matter of fact the weather service (now Environment Canada) gave me a plaque [saying] I survived 132-inch snow. …”10

The Expos were a much-improved club in 1970, going 73-89. McGinn had another 7-10 record, but his ERA was higher, at 5.44. He pitched in fewer games, 52, but had 19 starts, the first of which happened to be a 3-0 shutout of the Mets at Shea Stadium that ended Seaver’s 16-game winning streak going back to the previous season.

McGinn didn’t restrict his pitching to the regular season; he also threw in winter ball and in the instructional league. His arm didn’t get the rest it needed between seasons and, as he put it, he “ran out of gas.” The fatigue showed in spring training in 1971, causing the Expos sent him down to the Winnipeg Whips of the Triple-A International League to start the year. After going 6-6 in 14 appearances (13 starts) with a 3.89 ERA, he returned to Montreal, but was not effective, going 1-4 with a 5.96 ERA and no saves. The Expos traded McGinn and a player to be named later to the Chicago Cubs before the 1972 season in exchange for infielder Hector Torres and first baseman Hal Breeden.11 McGinn was happy to go to Chicago because it was near South Bend, Indiana, where he had friends from his days at Notre Dame. He also had the opportunity to play for Leo “The Lip” Durocher.

“We played at 1:30 and (Durocher) would get there around 12:45,” recalled McGinn. “He was outspoken, he was a pretty flashy guy, but he was out of touch with things then. From what I saw he was more of a figurehead than he was actually running the club.”

After going 0-5 with a 5.89 ERA in 1972, he began the 1973 season with the Wichita Aeros, the Cubs’ affiliate in the Triple-A American Association. That May the Cubs traded him to the Tulsa Oilers, the Cardinals’ American Association team, in a deal for pitcher Wade Blasingame. For the season, his last in professional baseball, McGinn went 3-6 with a 5.40 ERA.

After his baseball career ended, McGinn returned to Omaha and spent 24 years working for AT&T in sales and marketing, eventually becoming a national account manager, handling large national accounts, until he retired at age 54. He then scouted for the Phillies for six years.

In 2000 he joined the University of Nebraska Omaha’s baseball team as the pitching coach and was still in the position as of 2014.

“It’s been fun to work with young kids and see the light bulb go on now and then when they figure it out,” said McGinn.

McGinn was married to his wife, Rhea, on October 5, 1968. Both their sons, Shaun, who was born in Montreal, and Mark, played minor-league ball. Shaun played shortstop in the Phillies minor-league system, and also did scouting and front-office work for the Royals and Twins. Mark was drafted by the Mets as a pitcher; after his baseball career ended, he returned to Omaha to become a home builder. McGinn also has a grandson, Liam, born in 2011. According to McGinn, Liam has a good throwing arm.

Last revised: November 20, 2014

Sources

Gagnon, Cappy, Notre Dame Baseball Greats: From Anson to Yaz (Charleston, South Carolina: Arcadia Publishing, 2004).

Circleville(Ohio) Herald.

Ottawa (Ontario) Journal.

Valparaiso (Indiana) Vidette-Messenger.

University of Notre Dame Athletic Department.

baseball-reference.com.

Many thanks to Dan McGinn for graciously giving his time.

Notes

1 All quotes, unless otherwise specified, are from a telephone interview conducted with Dan McGinn on October 5, 2014.

2 Dick Becker, “Devaney Airs Defection Gripes,” Lincoln (Nebraska) Evening Journal, September 5, 1962.

3 Freshmen did not play on the varsity squad then.

4 Cappy Gagnon, Notre Dame Baseball Greats: From Anson to Yaz, (Charleston, South Carolina: Arcadia Publishing, 2004), 116.

5 Ibid.

6 Record confirmed by University of Notre Dame Sports Information department.

7 The Pilots became the Milwaukee Brewers prior to the 1970 season.

8 McGinn interview.

9 McGinn interview.

10 McGinn interview.

11 Bill Kelso went to the Cubs in June 1972 to complete the trade.

Full Name

Daniel Michael McGinn

Born

November 29, 1943 at Omaha, NE (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.