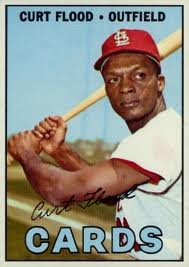

Curt Flood

Curt Flood was a vital cog in the 1964 Cardinals’ world championship run, but that achievement may have been all but forgotten in light of Flood’s subsequent role in the arrival of free agency for baseball players.

Curt Flood was a vital cog in the 1964 Cardinals’ world championship run, but that achievement may have been all but forgotten in light of Flood’s subsequent role in the arrival of free agency for baseball players.

Curtis Charles Flood was born in Houston, Texas, on January 18, 1938. His parents, Herman and Laura Flood, moved the family to Oakland, California, when Curt was a toddler. He was the youngest of six children, two of whom, sister Rickie and a brother, Alvin, were the product of his mother’s first marriage. Curt’s other siblings were Barbara, Herman Jr., and Carl. Curt’s relationship with Carl would prove to be particularly complex over the course of their lives. As children they were both athletic and artistic. In addition, Carl was incredibly intelligent and charismatic, but as Curt later said, his brother “treated his gifts as if they were a curse. He took awful chances and paid awful prices.”1 Carl’s behavior caused problems for Curt years later.

Flood said of his childhood, “We were not poor, but we had nothing. That is, we ate at regular intervals, but not much.”2 Initially settling in a middle-class, mostly white neighborhood in East Oakland, they later moved into a less affluent neighborhood in west Oakland in order to get away from the growing hostility of local whites after World War II. Herman found steady work during the war in various defense-related industries around Oakland, and Laura ran a small café and mended parachutes to make ends meet. After the war, they both worked in menial jobs at Fairmont Hospital.

When he was 9 years old, Curt joined the Juniors Sweet Shop team in a local midget league. The team was managed by George Powles, a white man who coached baseball in local amateur leagues as well as at Hoover Junior High School and, later, McClymonds High. Over the years, Powles developed a significant cadre of talented baseball players who went on to play major-league baseball.3 He also treated his players with great kindness. Flood’s interactions with Powles began to change the way he viewed the relationship between whites and blacks: “If I now see whites as human beings of variable worth rather than as stereotypes, it is because of a process that began with George Powles.”4

Jim Chambers, Flood’s art teacher in junior high school, was impressed with his skills with a brush and pencil and attempted to develop in him a broader appreciation for his talents. “Before I met him, I sketched and painted but had not the slightest sense of the larger significance of art,” Flood said. “…He taught me art not as technique alone but as one of the great resources of the human spirit.”5 As a teen, Curt created the artistic backgrounds for school proms and plays. He also earned extra money designing storefront window displays and advertising signs for a furniture store owned by Sam Bercovich. Later on in St. Louis, Flood received recognition for oil portraits of Cardinals owner August A. Busch, Jr., and Martin Luther King; the King portrait was presented to King’s widow, Coretta Scott King, who years later gave it to President George W. Bush to hang in the White House.6 Teammates and other players around the league also commissioned family portraits from Flood and called him “Rembrandt.” Flood later explained, “Baseball and painting make a good balance. Baseball is virile. It’s rough and tough. Painting is sensitive; quiet. It’s an outlet to overcome tension.”7

Flood played for Powles on the Bill Erwin American Legion team while he was still in junior high. He attended McClymonds High School in West Oakland for a year before transferring to Oakland Technical High School. A biographer, Brad Snyder, asserts that the move was engineered by George Powles and Sam Bercovich so that Flood could continue to play for the Bill Erwin American Legion team. Curt played third base and hit .440 for the Legion team in 1954; in 1955 he was named captain, moved to center field, hit .620 in 27 games, and helped lead the team to the state championship. In addition to his American Legion play, Curt played for semipro teams coached by Powles in the Alameda Winter League.8

Powles was a bird-dog scout for the Cincinnati Redlegs (as they were called then). After Flood graduated from high school in 1956, he signed a contract with the Redlegs for $4,000 (no bonus) and an invitation to spring training camp in Tampa, Florida. If Curt had been shielded to some extent from the ugliness of racial hatred while growing up in California, his bubble burst when he was ushered out of a side door of the Redlegs’ training camp hotel and hustled across town to Ma Felder’s boarding house, where the black players were housed:

“Until it happens you literally cannot believe it. After it happens, you need time to absorb it. … Rules had been invoked and enforced. I was at Ma Felder’s because white law, white custom and white sensibilities required me to remain offstage until needed. I was a good athlete … but this incidental skill did not redeem me socially. Officially and for the duration, I was a nigger.”9

Flood was assigned to Cincinnati’s team in High Point-Thomasville of the Class B Carolina League for 1956. He played well despite the subjugation of his humanity to the social mores of the times. He could not stay in the same accommodations as his white teammates; he could not eat in restaurants with his teammates and was forced instead to go to the back door for “service” or to wait on the team bus until a teammate brought him food. He could not use the restroom in the gas stations where the team bus stopped; instead the bus would stop on some deserted stretch of highway where Curt could disembark and “wet the rear wheel.” Fans around the league expressed their displeasure at the appearance of a black man on the diamond as well:

“One of my first and most enduring memories is of a large, loud cracker who installed himself and his four little boys in a front-row box and started yelling ‘black bastard’ at me. I noticed that he eyed the boys narrowly, as if to make sure that they were learning the correct intonation.”10

His teammates and manager weren’t any more supportive. “Most of the players on my team were offended by my presence and would not even talk to me when we were off the field. The few who were more enlightened were afraid to antagonize the others. The manager, whose name mercifully escapes me, made clear his life was already sufficiently difficult without contributions from me. I was completely on my own.”11

Flood’s acclimatization to his situation was difficult at first. It was not uncommon for him to return to his room late at night after a game and cry at the treatment he received. Thoughts of quitting entered his mind but, as he said later, “…What had started as a chance to test my baseball ability in a professional setting had become an obligation to measure myself as a man. These brutes were trying to destroy me. If they could make me collapse and quit, it would verify their preconceptions. And it would wreck my life. … Pride was my resource. I solved my problem by playing my guts out. … I completely wiped out that peckerwood league.”12

Flood led the league with a batting average of .340. He set a team record with 29 home runs and a league record with 133 runs scored. He finished second in runs batted in with 128. He also covered a lot of ground in the outfield, leading the league with 388 putouts. He was named the league’s Player of the Year and earned a late-season call-up to the Redlegs. He made his major-league debut as a pinch-runner on September 9, 1956, in St. Louis. Three days later, in his only official at-bat of the season he was struck out by Johnny Antonelli of the New York Giants. The highlight of his stint with the big club was the opportunity to be on the same field as one of his heroes, Jackie Robinson. After the season, Flood briefly played winter ball in the Dominican Republic.

Flood started the 1957 season with Cincinnati but soon was sent to the Savannah team of the Class A South Atlantic League. The Redlegs moved him to third base at Savannah, believing it might speed his development. Flood hit .299 in Savannah and led the league in runs scored with 98. He was named to two league all-star teams. He also committed 41 errors at third base. He endured many of the same indignities he had suffered at High Point-Thomasville, if not more.

Called up to Cincinnati again at the end of the 1957, Flood went to bat just three times, but got his first major-league hit, a home run off the Chicago Cubs’ Moe Drabowsky. He played winter ball after the season in Maracaibo, Venezuela, with instructions to learn how to play second base. Then in December he received a telegram from Cincinnati telling him he had been traded to the St. Louis Cardinals. (He was part of a five-player deal.) If Flood had any trepidation about the trade, it was swept away when he received a contract for $5,000 for the 1958 season.

Flood began the 1958 season with the Cardinals’ Double-A team in Omaha. After hitting .340 in 13 games he was called up. He took over as the starting center fielder under manager Fred Hutchinson and hit well for the first couple of months. A 13-game hitting streak between June 22 and July 3 raised his batting average to .331. As the season wore on, however, Flood’s productivity dropped and he finished the year with an average of .261 and 50 runs scored in 121 games. It was a good, but not a great, rookie season. Defensively, he was already receiving accolades for his prowess in center field.

Flood married Beverly Collins in February 1959. She already had two small children, Debbie and Gary. Curt adopted her two children, and although he and Beverly had three children of their own (Curtis Jr., Shelley, and Scott) the marriage was not a happy one. The disharmony in his marriage, along with the financial pressures of providing for a family of seven, became a constant source of stress for Flood that became worse after they divorced in 1966.

The Cardinals fired Fred Hutchinson before the end of the 1958 season. According to Flood, the new manager for 1959, Solly Hemus, was a racist who “did not share the rather widely held belief that I played center field approximately as well as Willie Mays. He sat me on the bench … (and) acted as if I smelled bad. He avoided my presence and when he could not do that he avoided my eye.”13 In 1959 Flood again played in 121 games for the Cardinals but had less than half as many at-bats (208) as he had in 1958 under Hutchinson. He batted just .255 and fell to .237 in 1960.14 Hemus was fired in July 1961 and was replaced by third-base coach Johnny Keane.

As much as Flood suffered under Hemus, he blossomed under Keane. In early August Keane installed him as the full-time center fielder and he and the Cardinals played well for the rest of the season. Flood finished the season with a .322 average in 335 at-bats. His offensive performance became more consistent as he recognized the need to cut down on his swing and learn to hit to all fields.

From 1962 through 1968, Flood enjoyed seven seasons of offensive excellence. He batted .302 during that time, including five seasons over .300 with a career high of .335 in 1967. He had 200 hits in 1963, and in 1964 he tied Roberto Clemente for the National League lead in hits with 211. He was an important cog in the Cardinals’ world championship teams in 1964 and 1967, as well as their National League championship in 1968. He was named to three All-Star teams. His defensive play was remarkable as well. In 1966 he handled 396 chances without an error. At one point he played 226 consecutive games without an error. He won the Gold Glove award six times during this period. The August 19, 1968, cover of Sports Illustrated pictured Flood making a leaping catch at Wrigley Field, with the caption “Baseball’s Best Center Fielder.” In 1965 he and Tim McCarver were named team co-captains, a title Flood held until 1969.

Flood’s personal life during this period had its ups and downs. In 1962 he met Johnny and Marian Jorgensen, an older white couple from Oakland’s Montclair district with whom he bonded closely. Johnny Jorgensen owned an industrial engraving plant and gave Curt an opportunity to learn the trade. Flood excelled at it; he and Johnny made plans for Curt to join the company as a partner when his playing days were over. The Jorgensens also opened their house to him, shared their extensive library with him, and even allowed him to live with them for a time. They spent many nights talking about politics and social issues. About first meeting the Jorgensens, Flood said, “I have relived that evening many times. … It was … an emotional discovery bordering on the spiritual. … What it boiled down to was that the Jorgensens and Flood loved each other on sight. … The Jorgensens’ wide interests aroused an intellectual hunger in me.”15

His family life was more unsettled. Beverly sued for divorce after the 1963 season and was granted an initial decree in March 1964.16 Later that spring, they began a process of reconciliation; Beverly became pregnant with their last child in May and they were remarried that fall after the 1964 World Series. The reconciliation did not last, however. Beverly sued for divorce again after the 1966 season and was awarded custody of the children and $1,400 a month in alimony and child support, in addition to one-half of their community property.17

To make matters worse, Johnny Jorgensen was killed in late 1966 by a mentally unstable intruder. Curt was so concerned about Marian that he asked her to move to St. Louis to live with him and take care of his affairs. Marian moved to St. Louis after the 1967 season.18

After his divorce Flood moved back to St. Louis and took up residence in a fashionable area. As one publication noted, “Off the field, he was the darling of the St. Louis fans. They marveled at his ability as a fine painter; admired his expensive clothes, and gossiped about his jet-setting exploits. Curt Flood was a man with the world in his hands.”19 He became involved in a number of personal relationships, some more serious than others; among those relationships was one with actress Judy Pace.20

Flood’s increasing popularity led to the creation in 1967 of Curt Flood Associates, Inc. It was run by Bill Jones, a business promoter and an acquaintance of Flood’s. A Curt Flood Photography studio opened with the goal of getting a significant piece of the school picture business in the St. Louis area, selling photography studio franchises, and obtaining portrait commissions for Flood. He was not involved in the day-to-day business of CFA; he was the celebrity “face” of the company.

In 1968 Flood hit .301 as St. Louis won the National League pennant and faced the Detroit Tigers in the World Series. The Cardinals took a three-games-to-one lead, but Detroit won Games Five and Six to even the Series. Game Seven was a pitcher’s duel between Bob Gibson and the Tigers’ Mickey Lolich. With the game scoreless and two outs in the top of the seventh, the Tigers had two runners on base when Flood misjudged a liner off the bat of Jim Northrup and slipped trying to reverse his direction. Northrup ended up with a triple and the Tigers won the game, 4-1. Flood was branded the “goat” of the Series.

The next year, 1969, was a disaster for the relationship between Flood and the Cardinals. The club offered him a nominal raise for the season. Flood rejected the offer and pointedly told the Cardinals front office that he would not play for less than $90,000 in 1969. (The Cardinals had offered “just” $77,500 for the year. He made $72,500 in 1968.) His demand, and the way it was expressed, became public knowledge and did not sit well with team officials. Then, in the middle of spring training, Carl Flood’s problems came back to haunt his brother. Carl, who had been imprisoned for bank robbery, was living in Curt’s apartment in St. Louis after being released on parole. In March 1969 he and an acquaintance tried to rob a jewelry store. They took hostages and a police car and proceeded to lead the police on a chase through the streets of downtown St. Louis before finally being caught. All of this was televised by KMOX-TV in St. Louis, and Carl was identified prominently as Curt’s brother. The St. Louis brass did not appreciate the negative publicity.

A couple of days later, August Busch delivered a now-famous lecture to his players at a spring-training meeting to which front-office personnel, Anheuser-Busch directors, and the press were invited. Busch admonished his players not to be so greedy, to devote themselves singularly to their performance on the field and to be more aware of the need to foster positive relationships with the fans and press. Flood, among others, viewed the speech as a direct threat to his long-term position with the team.

“In 1969, we lost the championship of the National League on March 22, before the season started. “I feared that if I so much as hinted at the truth about that meeting I would be gone from the team in a week. I was sick with shame and so was everyone else on the Cardinals. … The speech demoralized the 1969 Cardinals. … We became a morose and touchy team.”21

Embarrassing Flood even further, at some point before the season he was removed as co-captain of the team.

Flood’s relationship with the front office became even more strained as the season wore on. He missed an important public function in May, drawing the wrath of the front office and a $250 fine. Flood was incensed that the front office failed to take into account the fact that he had been severely spiked during the previous night’s game and had spent a restless night dealing with the pain and the effects of the painkillers he had been given. As August turned into September, the local press reported on comments from Cardinals veterans criticizing the front office for giving up on the team’s chances to make the postseason by making manager Red Schoendienst play several rookies late in the season. Flood was the source of much of that criticism and although his name was never mentioned, the Cardinals front office, including general manager Bing Devine, suspected that he was responsible for those comments. The Cardinals finished in fourth place in the National League’s new East Division with a record of 87-75, 13 games behind the division champion New York Mets. Flood finished with a .285 average, 80 runs scored (his highest total since 1965), and another Gold Glove award.

On October 8, 1969, Flood received a call from Jim Toomey, an assistant to Devine, informing him that he had been traded to the Phillies. He did not react well to the news of the trade. In addition to the realization that he was leaving his St. Louis family, he was resentful that he had received the news from a “mid-level front office coffee drinker” instead of Devine. Then, thinking about his apparent destination:

“Philadelphia. The nation’s northernmost southern city. Scene of Richie Allen’s ordeals. Home of a ballclub rivaled only by the Pirates as the least cheerful organization in the league. When the proud Cardinals were riding a chartered jet, the Phils were still lumbering through the air in propeller jobs, arriving on the Coast too late to get proper rest before submitting to murder by the Giants and Dodgers. I did not want to succeed Richie Allen in the affections of that organization, its press and its catcalling, missile-hurling audience.”22

Flood talked to Phillies general manager Bob Quinn, who offered him a salary package of $100,000 for 1970. Flood had few options. He did not want to go to Philadelphia and did not want to retire. He could not sell his services to another team because of the reserve clause. The reserve clause (Paragraph 10 in the Uniform Player Contract) gave a club the right to renew a player’s contract for a period of one year in perpetuity. Flood consulted a local attorney, Allan H. Zerman, who discussed with him the possibility of suing Major League Baseball. In 1890 Congress had passed the Sherman Anti-Trust Act. The legislation was intended to prevent collusion and monopolistic business practices designed to restrain trade and/or commerce among the various states (i.e., “interstate” commerce). The reserve clause prevented players from selling their talents to the highest bidder. Such a system certainly worked to the owners’ advantage by keeping their labor costs artificially low and their profits artificially inflated. Flood noted at the time, “Unless I have misread history, we have passed the stage where indentured servitude was justifiable on the grounds that the employer could not afford the cost of normal labor.”23

Baseball had been sued before for alleged violations of the Sherman Act. In 1922 the US Supreme Court, in Federal Baseball Club of Baltimore, Inc., v. National League of Professional Baseball Clubs, ruled that baseball was exempt from the Sherman Act because it was not engaged in interstate commerce. The act of playing baseball, the court said, was a local activity insufficiently connected to the concept of interstate commerce to bring it under the umbrella of the law.24 Thirty years later, in Toolson v. New York Yankees (1953), the court upheld its 1922 decision. The decision in Toolson seemed to suggest, however, that the logic behind the decision in Federal Baseball was no longer valid. Since Federal Baseball, the court had expanded significantly its definition of interstate commerce (thereby expanding the range of activities within Congress’s power to regulate), but the justices at the time of Toolson were not inclined to examine the evolution of precedent in regard to that concept. Since Congress in the intervening years had not attempted to explicitly bypass the court’s earlier opinion, the Toolson court declined to overturn its own precedent. Ironically, the Supreme Court never applied the logic of Federal Baseball to other sports. Football, basketball, hockey, etc., did not enjoy the same protection from antitrust laws that professional baseball then enjoyed.

Flood turned to Marvin Miller, the executive director of the players union (the Major League Baseball Players Association). Miller took Flood through the existing legal precedent. He told Flood the odds were very much against him. A legal challenge would be very expensive and might take two years or more; even if he won, it was unlikely Flood was going to benefit directly from his victory. If he sat out two years, he would be 34 or 35 before the lawsuit was over. Owners were not likely to want him on their club if the lawsuit was decided in his favor, if at all, and he was not likely to receive any type of large financial windfall if he won. In the meantime, Flood would be forfeiting significant compensation he would have received had he played instead of suing. Finally, he could forget any ideas about becoming a coach or manager at some point in the future.

Once Miller was convinced that Flood was committed to the cause, he invited him to the Players Association’s executive committee meeting in San Juan, Puerto Rico, in early December to plead his case to the union and seek their financial support. Flood received their unanimous blessing and commitment to finance the lawsuit.25 In return he agreed to let the union choose his legal counsel. Miller already had someone in mind: Arthur Goldberg, his former colleague in the United Steelworkers union, a former secretary of labor under President Kennedy, and a former associate justice of the US Supreme Court. Goldberg seemed like an obvious choice.26

Thus the wheels were set in motion, starting with Flood’s letter to Baseball Commissioner Bowie Kuhn on December 24, 1969: “After twelve years in the Major Leagues, I do not feel that I am a piece of property to be bought and sold irrespective of my wishes. … I believe I have the right to consider offers from other clubs before making any decisions. I, therefore, request that you make known to all Major League clubs my feelings in this matter, and advise them of my availability for the 1970 season.”

As expected, Flood’s request was summarily rejected by the commissioner. His letter was made public, as was his intention to sue. A large segment of the national press and most fans could not understand how someone who made $90,000 playing baseball could be unhappy or view himself as a “slave.” Flood’s claim on a nationally televised show that “a well-paid slave is, nonetheless, a slave” did not help his cause.27 He came off as a whining ingrate who threatened to destroy the national pastime. Baseball reacted by noting that the reserve clause was the linchpin of professional baseball and had served it well for many years. Its abolition would destabilize the game by allowing the rich teams to sign the best free agents, thus destroying competitiveness. It would encourage corruption among the players; players might throw games in favor of opposing teams with whom they might later sign huge contracts for the following season.

The trial in Flood v. Kuhn began on May 19, 1970, in federal court in New York City and lasted three weeks. On August 12 the court issued its ruling in favor of the owners. Flood’s legal team appealed the ruling to the US Court of Appeals. That court also ruled against Flood, in April 1971. The Supreme Court accepted the case for review, and oral arguments were heard on March 20, 1972. On June 19 the court ruled against Flood by a vote of 5-3.28 Justice Harry Blackmun’s majority opinion acknowledged that the logic behind baseball’s antitrust exemption as laid down in Federal Baseball and affirmed in Toolson was an “aberration,” but that it was up to Congress to remedy the situation.29

Why, then, has Flood come to be viewed as the father of free agency? The 1968 Basic Agreement between the owners and players expired after the 1969 season. With negotiations on a new agreement taking place and the cloud of Flood’s lawsuit hanging over their heads, the owners and players agreed on a new Basic Agreement for 1970 that allowed the players to take grievances to independent arbitration, a huge concession on the part of management. Flood’s challenge to the reserve clause raised public awareness of the one-sided nature of the system. It raised awareness among the players as well, many of whom had blindly bought into management’s arguments without really thinking about the inherent inequities in the system. Baseball had argued in court that the reserve clause was a subject that should be dealt with through negotiation (despite their unwillingness to do so over the course of the previous two years) and not in the courts. Now the pressure was on the owners to engage in meaningful negotiations. Changes to the reserve system were most likely to occur through negotiation, as Miller had always expected.30 Over the years, the players would chip away at the reserve clause piece by piece. The arbitration component of the 1970 Basic Agreement was the key that opened the door. In 1974 Catfish Hunter won his freedom from the Oakland Athletics when an arbitrator ruled that Athletics owner Charles Finley had violated the terms of Hunter’s contract. The following year, Miller used the arbitration process to win free agency for Andy Messersmith and Dave McNally, who had played the 1975 season without contracts. They argued that the owners’ right to renew a player’s contract was good for only one year if a player had refused to sign a new contract. To the shock and dismay of the owners, the arbitrator, Peter Seitz, agreed, changing the owner-player relationship forever. After that decision, the players were able to win significant modifications to the reserve clause through the negotiation process, although those negotiations were not always easy. In 1973, the Players Association was able to negotiate a new agreement that included the “10/5 Rule” (also known as the “Curt Flood Rule”), which gave players with ten years of major league experience, including five years with their current club, the right to veto a trade. Other concessions from the owners would follow in later years.

While the lawsuit progressed, personal problems were mounting for Flood. He quit paying child support a few weeks after the 1968 World Series and was in serious arrears to his ex-wife.31 His business interests in St. Louis were failing; bills were not being paid, resulting in several lawsuits against CFA, Inc., and Flood himself. Worse still, payroll taxes were not being paid to the Internal Revenue Service. The IRS went after the assets of the photography business and threatened to take an apartment building in Oakland that Flood had purchased for his mother. Curt, by his own admission, spent most of 1970 “bedding and boozing” instead of taking care of business. With little or no income being generated, he was facing serious financial problems. A few weeks after the district court trial was over, with his business interests in St. Louis in tatters, Flood flew to Copenhagen to get away from the stress and media frenzy. It was there that he learned he had lost his case in the district court.

Then, in October of 1970, Flood received a phone call from Washington Senators owner Bob Short. Short had reached a deal with the Phillies that allowed him to negotiate with Flood to bring him to the Senators for the 1971 season. After determining that returning to active status would not threaten his legal standing to pursue his case in the appellate courts, Flood and Short agreed on a contract worth $110,000 for the 1971 season. There also was a verbal agreement that Short would grant Flood his release after the season if Flood so desired.32

In retrospect, the move seemed destined to failure. During his hiatus from baseball, Flood had done nothing to stay in shape. To the contrary, as one biographer noted “(w)ithout baseball, drinking had come to dominate Flood’s life. He no longer had an incentive to remain sober each day.”33 In November Flood reported to the Senators’ facility in the Florida Instructional League at St. Petersburg to begin light workouts. He had difficulty completing even the most basic drills. He was clearly out of shape.

The Senators’ spring-training camp in Pompano Beach, Florida, opened in February 1971, at about the same time Flood’s book, The Way It Is, was published. 34 While everyone smiled for the cameras and said all the right things to the reporters gathered there, it became very apparent that his skills had declined significantly. Many felt Flood did not have his heart in the comeback; he had, after all, returned primarily for financial reasons. He stayed to himself and drank heavily in his hotel room at night. As Brad Snyder noted, “Flood read books on the bus during spring training road trips. He kept his distance from most teammates. They liked him and admired him, but also pitied him. They knew he was not the player he had once been.”35 Senators manager Ted Williams publicly supported Flood but told people privately that Flood was finished. Nevertheless, Flood was the Opening Day center fielder. He batted second in the game against Oakland, getting a bunt single, walking twice, and scoring two runs. After that, things on the field quickly deteriorated for Flood. He failed to hit with any consistency or power. He had lost the gracefulness that previously characterized his outfield play, and he could not throw with any strength. Williams benched him after just five games, relegating him to pinch-hitting duties and occasional late-inning defensive substitutions. Flood’s financial difficulties, in addition to his alcoholism, had taken a severe physical and psychological toll on him. His inability to perform on the field in the glare of the public spotlight pushed him over the edge. On April 26 he left the team without warning, deciding instead to flee the country to escape the mounting pressures. From the airport in New York, he sent Bob Short an apology in the form of a telegram, saying only that he had been away from the game too long and that he had serious financial troubles. Flood went 7-for-35 (.200) in his comeback with no extra-base hits in 13 games.

Flood eventually settled on the Spanish island of Majorca. He was in dire straits financially. Beverly had sued him again to try to recover a significant sum in back alimony and child support, and he was still responsible for judgments arising out of his failed businesses in St. Louis. He invested in a bar, the Rustic Inn, in the town of Palma with a new-found girlfriend. The island was a popular resort and American tourists, including vacationing Hollywood crowds, and military personnel stationed in the Mediterranean frequented the bar. Howard Cosell, the broadcaster, went so far as to send videotapes of boxing matches to Flood to show at the bar.

In 1975 Flood was forced to give up the Rustic Inn and leave Majorca. He later claimed that the Spanish police suspected illegal activities because of the heavy traffic at the bar. Flood went to the tiny principality of Andorra, located between Spain and France, where he continued to drink heavily and lived out of a duffle bag with whoever was kind enough to offer him a place to stay. Hitting rock bottom on October 1, Flood tried to rob a department store while in a drunken stupor. The charges were dropped because he had been drunk and had not taken anything. He was immediately deported to Barcelona, Spain, where he was hospitalized for alcoholism. Spanish authorities, working through the US State Department, released Flood a few weeks later when someone in his family provided a plane ticket for him to return to Oakland.

Flood was destitute. His childhood benefactors in Oakland tried to help him. In 1978 Sam Bercovich purchased the radio broadcast rights for the Oakland games and persuaded the A’s to give Flood a job as color commentator. He struggled in that job, in part because of his alcoholism, failing to engage the audience with the kind of insight expected of a color commentator. Bercovich did not renew the rights after the season and Flood was out of a job. He also coached the American Legion team he had played for years earlier.

Another former mentor, Bill Patterson, got Flood a job with the Oakland Parks Department as commissioner of its youth baseball program. His primary duty was fundraising; the parks department paid for only 60 percent of the program’s cost. Curt enjoyed some success in this position; he arranged coaching clinics with a number of current and former major-league players and by all accounts was quite successful at raising money and obtaining donations of equipment.

In 1980 Flood entered a rehabilitation center and, for a while at least, he found sobriety.36 He also attempted to re-establish his reputation as a portrait painter, although it is not clear to what extent this effort was successful. In 1985, after 15 years apart, Flood rekindled his friendship with Judy Pace and moved to Los Angeles; they were married in December 1986. Judy was able to get him more help with his drinking; by the early 1990s he had achieved, and was able to maintain, his sobriety.

In 1989 Flood was named commissioner of the Senior Professional Baseball Association, a Florida-based league of retired players. The job paid $65,000 a year, but financial difficulties forced the league to fold after its second season. Flood later created the Curt Flood Youth Foundation, to help youngsters in foster care and those who suffered from HIV/AIDS.37 In 1994 he was featured in Ken Burns’ PBS documentary Baseball, discussing the difficulties he encountered as a black player coming of age in the 1950s and ’60s and his efforts to overturn the reserve clause. He was inducted into the Bay Area Hall of Fame in 1995. That same year, he was diagnosed with throat cancer. He died in Los Angeles from the effects of that disease on January 20, 1997. No then-current players attended the services.

In 1998 Congress passed the Curt Flood Act, which eliminated baseball’s antitrust exemption in regard to labor issues. Flood received one final posthumous accolade in 1999, when Time magazine named him one of the ten most influential athletes of the past century.

Curt Flood’s life came crashing down around him when he decided to sue baseball. There is no doubt many of his wounds were self-inflicted. But was it worth it? Did he have any regrets? Publicly, he never complained about the fact that he did not benefit from the changes that took place after his lawsuit. He told Ebony magazine in 1981, “I certainly don’t begrudge the players getting that money. They’re finally getting a fair share of the incredible amount of money they’re making for the baseball teams.” Several years later he privately admitted to some people that he might have paid too high a price. What seemed to bother him the most about his lawsuit was the lack of support he received from his peers during the district court trial. “I spent six weeks in New York during the trial … and not one player who was playing at the time came just to see what was going on because it involved them so dramatically. … (N)o one came to just sit and say, ‘Hey, this is pretty important.’”38 Even his best friend in baseball, Bob Gibson, told Curt, “You’re crazy,” and stayed away from the trial itself.39

Flood’s legacy continues to benefit players more than ever, even if his name has been lost to history. Brad Snyder summarized Flood’s place in most contemporary players’ lives: “Today’s athlete have some control over where they play in part because in 1969 Flood refused to continue being treated like hired help. But while [Jackie] Robinson’s jersey has been retired in every major league park, few current players today know the name Curt Flood, and even fewer know about the sacrifices he made for them.”40

A couple of years before Flood died, George Will wrote “He lost the 1970 season and lost in the Supreme Court, but he had lit a fuse. … Six years later – too late to benefit him – his cause prevailed. The national pastime is clearly better because of that. But more important, so is the nation, because it has learned one more lesson about the foolishness of fearing freedom.”41

This biography is included in the book “Drama and Pride in the Gateway City: The 1964 St. Louis Cardinals” (University of Nebraska Press, 2013), edited by John Harry Stahl and Bill Nowlin. For more information, or to purchase the book from University of Nebraska Press, click here.

Bibliography and Suggested Reading

Murray Chass. “Curt Flood – Baseball’s Forgotten Man,” Baseball Digest, January 1977

Curt Flood with Richard Carter. The Way It Is (New York: Pocket Books, 1971)

William Gildea. “Curt Flood – Baseball’s Angry Rebel,” Baseball Digest, February 1971

Neil Gross. “Curt Flood – His Teammates Call Him Rembrandt,” Ebony, July 1968

Marvin Miller. A Whole New Ballgame: The Sport and Business of Baseball (New York: Birch Lane Press, 1991)

Charles P. Korr. The End of Baseball As We Knew It: The Players Union, 1960-81 (Champaign, Illinois: University of Illinois Press, 2002)

Bowie Kuhn. Hardball: The Education of a Baseball Commissioner (New York: McGraw-Hill, 1988)

Brad Snyder. A Well-Paid Slave: Curt Flood’s Fight for Free Agency in Professional Sports (New York: Plume Publishing Co., 2007)

Stuart L. Weiss. The Curt Flood Story: The Man Behind the Myth (Columbia, Missouri: University of Missouri Press, 2007)

“What Ever Happened to … Curt Flood?” Ebony, March 1981

George Will. “Dred Scott in Spikes,” Syndicated newspaper article from November 21, 1993; reprinted in Will’s Bunts: Curt Flood, Camden Yards, Pete Rose and Other Reflections on Baseball (New York: Scribner, 1998)

2 Ibid, 8. Flood biographer Stuart Weiss argues that Flood’s childhood environment was not as deprived as Flood might have his readers believe. See Weiss’s The Curt Flood Story: The Man Behind the Myth.

3 Among Powles’ protégés were Billy Martin, Frank Robinson, Vada Pinson, Chris Cannizzaro, and Joe Morgan, in addition to Flood.

4 Flood and Carter, 14

5 Flood and Carter, 15

6 Some doubt has arisen in recent years about Flood’s oil portraits. According to Brad Snyder’s A Well-Paid Slave, Flood did not paint the oil portraits. Instead, he would send photographs of his subjects to one Lawrence Williams in Los Angeles, who would do the portraits and ship them back to Flood, allowing Flood to take all of the credit for the paintings. This includes the Martin Luther King portrait for which Flood was so widely acclaimed. Snyder asserts that the portrait was signed by someone else, although he doesn’t say who. Weiss disagrees with Snyder’s claims as they relate to the portraits done while Flood was still playing baseball. Both agree, however, that by the 1980s, when Flood tried to resuscitate this source of income, he could not possibly have done the portraits attributed to him at that time because of the effects of his alcoholism. A female companion of Flood’s at the time supposedly confirmed that he did not actually paint those portraits.

7 Neil Gross. “Curt Flood – His Teammates Call Him ‘Rembrandt.’ ” Ebony, July 1968, 70

8 When Powles died in 1987, Flood was the only one of his former big leaguers to attend the funeral.

9 Flood and Carter, 22

10 Ibid, 24

11 Ibid., 24. The manager was Bert Haas.

12 Ibid, 25

13 Ibid, 51. For those seeking a somewhat more detailed summary of Hemus’s treatment of his black players, see the profile of Bob Gibson elsewhere in this volume.

14 Weiss argues that Hemus’s failure to use Flood more regularly stemmed as much from his desire to find a power-hitting outfielder to boost the Cardinals offense as it did from Hemus’s supposed racism.

15 Flood and Carter, 92

16 Weiss asserts that the divorce decree was never finalized.

17 Weiss’s The Curt Flood Story: The Man Behind the Myth is the best source of detailed information about Flood’s financial obligations arising from his divorce.

18 Flood’s relationship with Marian Jorgensen was the subject of widespread speculation by people in St. Louis who knew him. By his own account the relationship was completely platonic.

19 “Whatever Happened to… Curt Flood?” Ebony, March 1981, 55

20 Among other roles, Judy Pace played the wife of Gale Sayers (Billy Dee Williams) in Brian’s Song.

21 Flood and Carter, 145-151

22 Ibid., 158

23 Ibid., 114

24 Over the years, many observers have incorrectly stated that the court in Federal Baseball said baseball was a sport, not a business, and therefore not subject to antitrust laws. The court never made that distinction.

25 A number of players publicly criticized Flood’s lawsuit and the executive committee’s decision to fund it. Among those voicing opposition were Carl Yastrzemski, Harmon Killebrew, and Frank Howard. Prominent former players also voiced opposition, including Ted Williams, Ralph Kiner, Joe DiMaggio, and Joe Garagiola. Garagiola, in fact, testified against Flood in the district court trial.

26 The selection of Goldberg turned out to be a disaster. He embarked on a campaign for governor of New York shortly after accepting the Flood case (and after promising Miller he had no intention of running for office). Goldberg was ill-prepared when the case came to trial in May 1970, although it is doubtful that his performance had anything to do with the final outcome.

27 Interview with Howard Cosell on ABC’s Wide World of Sports, January 3, 1970

28 Justice Lewis Powell recused himself from the case because he owned stock in Anheuser Busch, the parent company of the Cardinals.

29 Goldberg argued Flood’s appeal before the Supreme Court. As was the case in the district court, he was woefully unprepared and stumbled through a presentation that was painfully embarrassing both for him and the members of the court. It was the last case Goldberg ever argued before the Supreme Court.

30 Miller and the union never claimed that abolition of the reserve clause was the only way to satisfy the players’ grievances. In fact, Miller and the union recognized the owners’ need to have some control over players they had developed and invested in. Miller always expected that negotiation would be the means by which the reserve clause would be modified. Flood’s lawsuit arose precisely because the owners had failed to negotiate in good faith after the 1968 Basic Agreement, which created a joint committee to examine possible changes in the system.

31 According to Weiss, with the exception of a very brief period of time in 1982, Flood stopped making child support and alimony payments in October 1968. His ex-wife filed another lawsuit after his death trying to identify assets which might be confiscated in partial payment of his arrears.

32 Originally, Flood and Short agreed to a two-year contract at $100,000 per year without a reserve clause. Short readily agreed to Flood’s demands, but Bowie Kuhn later told Short he would reject any contract that did not contain the reserve clause.

33 Brad Snyder. A Well-Paid Slave, 132

34 Weiss characterizes Flood’s autobiography as an “apologia” for the lawsuit. Weiss paints a darker picture of Flood’s emotional state and motivations for his decision to sue baseball. He says Flood resorted to a “victimization” mentality to justify his inability or unwillingness to deal with the troubles in his life, including his failed marriage and resulting financial pressures, the guilt he felt from his gaffe in the 1968 World Series, and the volatile state of his relationship with the St. Louis front office during the 1969 season. He says the lawsuit was Flood’s irrational way of lashing out and blaming others for his troubles, despite the hardships his actions would place on his family and himself.

35 Snyder, 219

36 Snyder and Weiss both suggest that Flood started drinking again two or three years after leaving rehab.

37 Weiss claims that an investigation after Flood’s death showed the Curt Flood Youth Foundation to be of questionable viability. It was based in the Flood home in Los Angeles. It had scant financial resources. Judy Flood had been using foundation funds to pay the utility bills. Aside from one letter suggesting the foundation had found summer jobs for 35 youths, there was no evidence of significant assistance provided to anyone.

38 Murray Chass, “Curt Flood – Baseball’s Forgotten Man,” Baseball Digest, January 1977, 63

39 Gibson supported his friend privately but recognized, as did other players, that supporting Flood publicly would put a target on his own back. Gibson and others were not willing to sacrifice their livelihoods for the cause. Gibson did visit Flood in his hotel in New York during the trial when the Cards were in town playing the Mets.

40 Snyder, 2-3

41 From George Will’s November 21, 1993, syndicated article “Dred Scott in Spikes”

Full Name

Curtis Charles Flood

Born

January 18, 1938 at Houston, TX (USA)

Died

January 20, 1997 at Los Angeles, CA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.