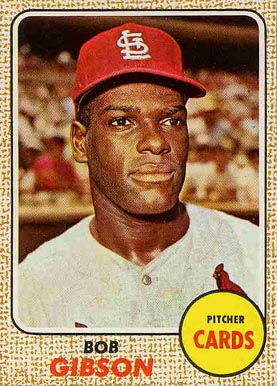

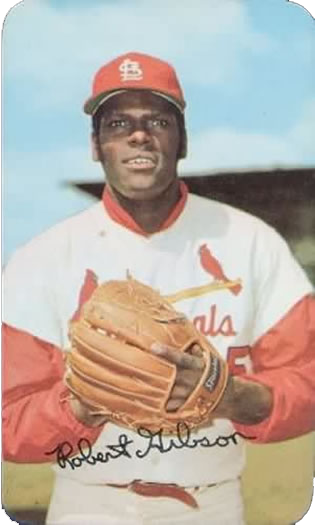

Bob Gibson

“Hoot, you’re on your way. Nothing can stop you now.” — From “Ghetto to Glory”

Prophetic words indeed. The 1964 World Series was a coming-out party for Bob “Hoot” Gibson. Pitching complete-game victories in Games Five and Seven, Gibson and his teammates on the 1964 St. Louis Cardinals had just disposed of the vaunted New York Yankees, bringing St. Louis its first world championship since 1946. The words were spoken to him privately by his manager, Johnny Keane, during the clubhouse celebration.

Prophetic words indeed. The 1964 World Series was a coming-out party for Bob “Hoot” Gibson. Pitching complete-game victories in Games Five and Seven, Gibson and his teammates on the 1964 St. Louis Cardinals had just disposed of the vaunted New York Yankees, bringing St. Louis its first world championship since 1946. The words were spoken to him privately by his manager, Johnny Keane, during the clubhouse celebration.

Keane had been Gibson’s first manager in professional baseball and, later, his savior. There were few men who could have spoken more meaningful words to Gibson at that moment. Gibson was named the Series MVP, and his performance put the rest of the baseball world on notice that he was a force to be reckoned with. When Keane was asked during the postgame press conference why he had stuck with Gibson in the finale even though he was obviously spent, Keane replied gently, “…I was committed to this fellow’s heart.”1

Over the next ten years, Gibson would carve out a reputation as one of the toughest competitors to ever play the game. His longtime catcher, Tim McCarver, once reflected on Gibson’s approach to pitching:

“For my money, the most intimidating, arrogant pitcher ever to kick up dirt on a mound is Bob Gibson. … If you ever saw Gibson work, you’d never forget his style: his cap pulled down low over his eyes, the ball gripped – almost mashed – behind his right hip, the eyes smoldering at each batter almost accusingly. … (He) didn’t like to lose to anyone in anything. … Bob was a man of mulish competitive instinct.”2

Gibson worked quickly, relying on pinpoint control of a vicious slider and two different fastballs for his success. His delivery, in which the right side of his body hurtled violently toward the first base line after he released the ball, gave hitters the impression that he was exploding toward the plate. He also took full advantage of his reputation as a pitcher who would not hesitate to hit a batter for the smallest of transgressions. That reputation was undeserved, at least in Gibson’s mind. He rarely hit batters deliberately. Any batter who got too comfortable in the batter’s box, any hitter determined to reach across the plate to drive an outside pitch, could count on getting shaved by an inside pitch. If the batter’s body happened to get in the way of the ball, if he had to go down on his backside to avoid getting hit, so be it. Gibson made no apologies.

He would not fraternize with opposing players, even when he played with them in All-Star Games. Joe Torre told a tale of catching Gibson in the 1965 All-Star Game. After the game, as they were showering, Torre complimented Gibson on his performance. Gibson didn’t say a word. He showered, got dressed, and left. His aloof demeanor carried over to the press as well. The press respected him, but few understood or knew him well.

Gibson was the first to admit that he was competitive; everything he did was geared toward winning. Winning was his raison d’etre. He was going to use every tool, physical and mental, to achieve that goal. He balked at some of the harsher descriptions of his attitude and pitching style.

“I’d like to think that the term ‘intensity’ comes much closer to summarizing my pitching style than do qualities like meanness and anger, which were merely devices. … My pitching career, I believe, offers a lot of evidence to the theory that baseball is a mental discipline as much as a physical one. … The part of pitching that separates the stars from everyone else is about 90 percent mental. That’s why I considered it so important to mess with a batter’s head without letting him inside mine.”3

Born in Omaha, Nebraska, on November 9, 1935, Pack Robert Gibson4 was the youngest of seven children. He was named after his father, who died shortly before Bob’s birth. His mother, Victoria, worked in a laundry and cleaned houses to make ends meet. Bob spent most of his childhood living in the Logan-Fontenelle housing project on Omaha’s north side.

Bob’s oldest brother, Josh, became his surrogate father and mentor. Josh was educated, earning degrees in history from Creighton University, near their home in Omaha. He became the program director at a recreation center near the projects and spent much of his life mentoring young boys in the local community. As Bob later recalled:

“He had always been the central figure in my life – father, coach, teacher, and role model. … Josh led by example. He required no more from any of us than he gave himself. … He would have loved to have the opportunity … to pursue a career in professional sports. … But since that avenue was closed for him – the color barriers were not broken in time to help Josh – he did as he told me I would otherwise have to do: He got an education. And don’t think the boys on the team didn’t notice. … We were all, one way or another, a reflection of Josh.”5

Josh organized youth sports teams – primarily basketball and baseball – at the recreation center, and Bob spent much of his early childhood there watching and, eventually, playing ball with his brother. On the Y Monarchs, the baseball team, Bob was a catcher and shortstop while pitching only occasionally. He was lean, strong, and quick; he became a switch-hitter who could hit for high average with some power. In 1951 the Monarchs became the first black team ever to win the American Legion city championship. Bob was selected to the all-city team as a utility player.

Bob’s favorite sport, however, was basketball. In addition to playing on the recreation center teams, he played on the Omaha Technical High School team for two seasons and was a unanimous choice for the all-city team in his senior season.

Gibson was not allowed to try out for the baseball team during his junior year, ostensibly on the grounds that he had reported a day late for tryouts. Several years later he discovered he had been excluded because the coach at that time did not allow blacks on the team. Instead, he ran track that year, setting an Omaha indoor record in the high jump and also participating in the broad jump and sprint relays. By Gibson’s senior season, a new baseball coach was in place at Tech and Bob joined the team, playing the outfield and pitching. He finished second in batting average among city players at .368. Tech won the intercity tournament and Gibson was selected to the all-city team as a utility player.

After high school, Cardinals scout Runt Marr offered him a very modest contract but his brother Josh insisted he should go to college. Bob tried to get a basketball scholarship to Indiana University but was denied entry because the school “already had its quota of Negroes.” Thanks to Josh’s connections at Creighton University, Bob became the first African-American to receive a basketball scholarship from the Blue Jays. By the time his career at Creighton was over, Gibson was the university’s all-time leader in points per game (20.2) and third in total points (1,272). Gibson’s basketball jersey number (No. 45) is one of three that have been retired by Creighton (as of 2011), along with Paul Silas’s and Bob Portman’s.6

Gibson also played baseball at Creighton, although baseball was treated as a minor sport at the time. His first baseball coach was Bill Fitch, an aspiring basketball coach who had been hired to coach baseball. (Fitch went on to have a successful coaching career in the NBA.) Bob was a superb utility player at Creighton, where he caught, pitched, and played third base and the outfield. In his senior year he led the Nebraska College Conference with a .333 batting average and went 6-2 as a pitcher. The Dodgers, Yankees, White Sox, Phillies, and Athletics all contacted him about playing professional baseball, but none offered a substantial bonus. He seemed to have flown below the radar of most NBA scouts as well. The Minneapolis Lakers were the only NBA team to talk to him, but they never made an offer.

Opportunities to play both sports eventually developed, however. The Harlem Globetrotters were barnstorming the country exhibiting their brand of highly entertaining basketball against a group of college all-stars that accompanied them on their tours. For publicity, the Globetrotters typically asked a local college player in each city in which they played to join the all-star team. When the Globetrotters played in Omaha in the spring of 1957, Gibson was asked to join the collegians for that game. When given the chance to play late in the third quarter, Gibson made such an impression that he was recruited to join the Globetrotters. Gibson, who had married Charline Johnson the previous day, told the Globetrotters he could not consider their offer until the baseball season and school were over. The Cardinals were still interested in him as well. Gibson finally negotiated a deal that allowed him to play the rest of the baseball season in the Cardinals’ minor-league system, after which he would join the Globetrotters for four months. At the end of his four months with the Globetrotters, Gibson and the Cardinals agreed on a deal that allowed Bob to focus solely on baseball.

Gibson reported to Triple-A Omaha of the American Association in June 1957. Johnny Keane, who was managing Omaha, determined that Gibson should focus on pitching. Gibson was taken by the fact that Keane “had no prejudices concerning my color. … He was the closest thing to a saint that I ever came across in baseball.”

Gibson appeared in ten games for Omaha. He notched his first win on June 23, defeating Columbus (Ohio), 4-3. He posted a 2-1 record before being sent to the Class A Columbus, Georgia, farm club (South Atlantic League) in July. It was there that Gibson first faced a blatantly hostile environment in which blacks were subjugated to second-class citizenship (at best) every day and in every aspect of life. That’s not to say there hadn’t been problems while he was growing up in Omaha; certainly he had encountered episodes of racial bigotry when he was younger.

In Columbus Gibson became aware of the extent to which racial hatred had been institutionalized throughout all aspects of Southern society. He was forced to live and eat in the “black” part of town, away from his teammates. Local fans did not hesitate to voice their racial prejudices at the ballpark. Bob was exposed to racial taunts and language he had never heard before. Thankfully for him, his time with Columbus was brief. He appeared in eight games, all as a starter, finishing 4-3 with a 3.77 ERA.

At spring training with the Cardinals in St. Petersburg, Florida, in 1958, Gibson was subjected once again to the humiliation of being forced to live apart from his white teammates. He split the season between the Cardinals’ Triple-A clubs in Omaha and Rochester and finished with an overall record of 8-9 and a 2.84 earned-run average in 33 games. League managers voted his fastball “best-in-league” after the season.

Gibson was a candidate for the Cardinals’ rotation in 1959, but establishing himself in the big leagues would prove difficult:

“The bad news was that my performance would be judged by the Cardinals’ overmatched new player-manager, a utility infielder named Solly Hemus. … (His) treatment of black players was the result of one of the following. … Either he disliked us deeply or he genuinely believed that the way to motivate us was with insults. … He told me, like he told Curt Flood, that I would never make it in the majors. … I made the team in 1959, but Hemus had me convinced that I wasn’t any damn good and, consequently, I wasn’t. …”7

Gibson made his major-league debut on April 15, 1959, pitching two innings of relief in a 5-0 loss to the Dodgers. He surrendered two runs, including a home run to Jim Baxes, the first batter he faced. For the next two seasons, Gibson shuttled back and forth between St. Louis and the teams in Omaha and Rochester. He finally returned to the Cardinals for good in June 1960. Gibson offered a sarcastic summary of the situation years later:

“My best hope lay in the fact that Hemus, as much as he seemed to dislike me, might not really know me. He kept calling me Bridges, confusing me with Marshall Bridges, who was several years older than me, skinnier, and pitched left-handed. But he was black. Solly got that much right.”8

Gibson was not alone in his assessment of Hemus’s dislike for black players. Curt Flood later said of his former manager: “Hemus did not share the rather widely held belief that I played center field approximately as well as Willie Mays. … He acted as if I smelled bad. … My roommate, Bob Gibson, was just as badly off. He could throw as hard as any man alive. … (Hemus) never used him if someone else was available.”9

All doubts about the genesis of Hemus’s attitude toward his black players vanished one day in Pittsburgh when, after a fight between Hemus and Pirates pitcher Bennie Daniels, Hemus told his club he had called Daniels a “black son-of-a-bitch.” Hemus’s revelation was not meant as an apology. As Flood noted later: “We had been wondering how the manager really felt about us, and now we knew. Black sons of bitches. … Until then, we had detested Hemus for not using his best lineup. Now we hated him for himself.”10

When the 1961 season began, Hemus used Gibson irregularly out of the bullpen and as a spot starter before giving him a place in the starting rotation. Independence Day came on July 6 that year for Gibson and the other black players on the club when Hemus was fired and replaced by Johnny Keane. “It was a whole new world for the black players,” Gibson said later. Flood echoed Gibson’s feelings about Keane: “Johnny Keane … was a man of great sensibility, with a great sense of leadership. …The most important thing, however, was this: Keane didn’t give a damn about color. He said ‘You’re my best nine men.’ What a powerful, supportive feeling that was!”11

Gibson went 11-6, and the team 47-33, after Keane took over. (They had been 33-41 under Hemus.) For the entire season, Gibson was 13-12 with a 3.24 ERA.

With Hemus gone and people like Gibson, Flood, and Bill White leading the way, the Cardinals established an atmosphere that virtually eliminated racial tensions among the individual players and allowed the team to go on to great success in the coming years. White players who were not inclined to be so open-minded were challenged by the black leaders on the club in a way that forced them to rethink their attitudes about race.

With Hemus gone and people like Gibson, Flood, and Bill White leading the way, the Cardinals established an atmosphere that virtually eliminated racial tensions among the individual players and allowed the team to go on to great success in the coming years. White players who were not inclined to be so open-minded were challenged by the black leaders on the club in a way that forced them to rethink their attitudes about race.

Tim McCarver, from Memphis, Tennessee, was hardly a beacon of progressive thinking when he first joined the Cardinals in 1959 at the age of 17. One sweltering day in spring training in his early years, McCarver got on the team bus after a game with an ice-cream cone. (Flood remembers it as a bottle of orange pop.) Gibson asked McCarver if he could take a lick of his ice cream. McCarver was clearly taken aback by the request and fumbled around for an answer before finally telling Gibson he’d “save him some.” Gibson used McCarver’s own prejudices to put him in an untenable position. His goal was not to exacerbate racial tensions between the players, however. His ultimate goal was to force his white teammates to confront their own racial bigotries. McCarver did change, and he and Gibson became good friends. As McCarver later recalled:

“I believe Bob taught me a good deal about relationships with other human beings. If I came to that first spring training with many of the preoccupations of my birthplace, it was probably Gibson more than any other black man who helped me to overcome whatever latent prejudices I may have had.”12

Curt Flood also exulted in the cohesiveness of the Cardinals of that era. They were

“… as close to being free of racist poison as a diverse group of twentieth-century Americans could possibly be. Few of them had been that way when they came to the Cardinals. But they changed. … The initiative in building that spirit came from black members of the team. Especially Bob Gibson. … (W)e blacks wanted life to be more pleasant, championships or not. … It began with Gibson and me deliberately kicking over traditional barriers to establish communication with the palefaces. … After breaking bread and pouring a few with us, the others felt better about themselves and us. Actual friendships developed. Tim McCarver was a rugged white kid from Tennessee and we were black, black cats. … Without imposing blackness on Tim or whiteness on ourselves, we simply insisted on knowing him and on being known in return.”13

With improved control over his fastball and slider, and the confidence of Johnny Keane, Gibson took his first steps toward star status in 1962. He made the National League All-Star team and finished with a 15-13 record and a 2.85 ERA. His season was cut short in September, however, by a broken ankle suffered during batting practice. Gibson was not very conscientious about rehabbing his ankle in the offseason; as a result, he got off to a slow start in 1963. The Cardinals were in the pennant race by midseason, however, and made a strong run in September before dropping out of the race. Gibson won 18 games that year, and the nucleus of the club that would win the pennant in 1964 had been established.

The Cardinals were far back in the standings in June of 1964 when they acquired an underachieving young outfielder, Lou Brock, from the Chicago Cubs. Paired with Curt Flood at the top of the order and batting in front of either Bill White or Dick Groat and then Ken Boyer, Brock saw his bat come alive and the Cardinals slowly moved to get back into the race. By late July their prospects were still so remote, however, that owner August Busch openly courted Leo Durocher as a possible replacement for Johnny Keane, and general manager Bing Devine was fired in August. The Cardinals managed to get within six games of the league lead with two weeks left in the season. An epic collapse by the Phillies, who lost 12 of their last 15 games, including a streak of ten straight, allowed the Cardinals to win the pennant on the last day of the season. Gibson pitched four innings of relief that day against the Mets to get the win, his 19th of the year. Years later, Gibson reflected on that Cardinal team:

“The Cardinals were the rare team that not only believed in each other but genuinely liked each other. … As a team, we would simply not tolerate any sort of festering rancor between us, personal or racial. … We bought our racial feelings out into the open and dealt with them. … I’m confident I had a lot to do with it, and so did guys like White and Flood. … (N)one of us gave an inch to racism. The white players respected that … and in turn we respected them. … Of all the teams I was on … there was never a better band of men than the ’64 Cardinals.”14

Johnny Keane resigned immediately after the 1964 World Series and was replaced by Red Schoendienst. Team chemistry wasn’t enough to carry the Cardinals through the 1965 and 1966 seasons. Although Gibson flourished during those seasons, winning 20 and 21 games, respectively, the Cardinals struggled. Production from both White and Boyer slipped precipitously in 1965, and after the season they, along with Dick Groat, were traded. After finishing seventh in 1965, the Cardinals only managed to improve to sixth place in 1966.

An improved offense led by Orlando Cepeda and the development of a number of young pitchers, including Steve Carlton, Ray Washburn, Dick Hughes, and Nelson Briles, allowed the Cardinals to make a shambles of the 1967 pennant race. They won 101 games and took the pennant by 10½ games over the San Francisco Giants. The development of the young pitchers was critical to the Cardinals’ drive to the pennant when Gibson was forced onto the disabled list on July 15 after suffering a broken leg. In that day’s game against the Pirates, a liner off the bat of Roberto Clemente caromed off Gibson’s right shin. Gibson pitched to three more batters before his leg finally snapped just above the ankle. The episode cemented Gibson’s reputation as a competitive, gutsy player.

He returned to the rotation in September and finished the regular season with a 13-7 record. He won all three of his starts in the 1967 World Series as the Cardinals defeated the Boston Red Sox in seven games. All three of his starts were complete games, giving him five consecutive World Series-game victories and adding to his reputation as a big-game pitcher. He also homered in Game Seven. He was named the World Series MVP for the second time. His first autobiography, From Ghetto to Glory, written with assistance from Phil Pepe, was published between the 1967 and 1968 seasons.

In what became known as the “year of the pitcher,” major-league baseball witnessed a number of amazing pitching feats in 1968. In the American League, the Tigers’ Denny McLain won 31 games, the first pitcher to win 30 games since Dizzy Dean in 1934. In the National League, Don Drysdale set a record of 58 2/3 consecutive scoreless innings pitched. Gibson’s performance in 1968 outshone them all, however. He finished with a record of 22-9 and a 1.12 ERA, the lowest earned-run average of any pitcher since the Deadball Era. He had his own streak of 47 scoreless innings. He threw 28 complete games, including 13 shutouts. He was voted league MVP and was a unanimous selection for the National League Cy Young Award, while the Cardinals again outdistanced their closest rival, the Giants, by nine games for their second consecutive pennant. Gibson’s dominance in 1968, along with the performances of Drysdale and McLain, was the driving force behind major-league baseball’s decision to narrow the strike zone and lower the mound from 15 to 10 inches for the 1969 season to invigorate the offensive side of the game.

Gibson defeated the Tigers and Denny McLain in the first game of the 1968 World Series, striking out 17 batters in a record-setting performance that most view as one of the most dominating performances in World Series history. He had another complete-game victory and hit his second World Series home run in Game Four, giving the Cardinals a 3-1 lead in the Series and giving Bob a record seven consecutive complete-game victories in World Series play. The Tigers won Games Five and Six, however, setting up a showdown between Gibson and Tigers lefty Mickey Lolich. Game Seven was scoreless in the seventh inning when Detroit, capitalizing on a misplay by Curt Flood in center field, scored three runs. Detroit won the game, 4-1.

Things went downhill for the Cardinals after 1968, although Gibson still had some productive seasons ahead of him. Cepeda, their clubhouse cheerleader, was traded to the Atlanta Braves for Joe Torre before the 1969 season. As the players union threatened to delay the start of the 1969 season with a strike, owner Busch publicly blasted his team in spring training for being complacent and too concerned with monetary matters, further lowering club morale. Although Gibson went 20-13 with a 2.18 ERA, the Cardinals dropped to fourth place in the National League’s new Eastern Division.

Gibson won 23 games and picked up his second Cy Young Award in 1970, although the Cardinals struggled. It was the last time he would win 20 games in a season. His record slipped to 16-13 in 1971, although he pitched his only no-hitter, on August 14 against the Pittsburgh Pirates in Three Rivers Stadium.

Gibson won 23 games and picked up his second Cy Young Award in 1970, although the Cardinals struggled. It was the last time he would win 20 games in a season. His record slipped to 16-13 in 1971, although he pitched his only no-hitter, on August 14 against the Pittsburgh Pirates in Three Rivers Stadium.

Gibson rebounded to win 19 games in 1972 and made his last appearance in an All-Star Game. In 1973 the Cardinals were in pennant contention in August when he tore knee cartilage while running the bases. The Cardinals didn’t play well while Gibson was out and lost the division flag to the Mets by 1½ games. Gibson’s season record was just 12-10.

By 1974 Gibson no longer had the stamina and strength to pitch with the overpowering style he had become accustomed to. His personal life also weighed heavily on him as he and his wife, Charline, divorced. He reached the 3,000-strikeout mark in July, the first pitcher in National League history to do so. The Cardinals were in contention right down to the final day of the season, however. In what must have been a bitter denouement, they lost a chance to win the division when Gibson gave up an eighth-inning home run to the Montreal Expos’ Mike Jorgensen and lost the game, 3-2. Gibson finished with a record of 11-13, his first losing season since 1960.

The 1975 season was Gibson’s last. He didn’t pitch well and was eventually sent to the bullpen. Gibson picked up his last win in the major leagues on July 27 in a relief appearance against the Philadelphia Phillies. Bob left the team prior to the last road trip of the season and called it a career. He finished with a career record of 251-174 and an ERA of 2.91. When he retired, his 3,117 strikeouts were a National League record and second overall only to Walter Johnson. He tossed 255 complete games, including 56 shutouts. He was 7-2 in World Series play and was selected to the All-Star team eight times. During his playing career, he was widely regarded as one of the best fielding pitchers of his generation, winning the National League Gold Glove award at his position each year from 1965 to 1973.15

Gibson got involved in a number of other activities after his playing days were over. In the early 1970s, before he retired, he did some postseason broadcasting work for ABC. He parlayed that experience into a stint on ABC’s Monday Night Baseball broadcasts for a couple of seasons after his retirement, and contributed to an HBO baseball series in 1978. He also did basketball commentary for a New York radio station and later for WTBS in Atlanta. He hosted a Cardinal pregame and postgame radio show for KMOX in the mid-1980s. In 1990 he joined the ESPN baseball broadcast team but quit after one season for family reasons. (He remarried in 1979, to Wendy Nelson. They had one son, Christopher, together. Gibson had two daughters, Renee and Annette, by his first marriage.)

Gibson was also involved in several commercial ventures in the Omaha area. He was the chairman of the board of directors of Community National Bank, which catered primarily to Omaha’s black community. He was the primary financial backer of a radio station in Omaha for several years before selling his stake. He was involved in a print advertising venture that had promise, but had to abandon that effort when, he asserted, many commercial establishments declined to do business with the firm after learning it was owned by blacks.

In the late 1970s, Gibson opened a restaurant near the Creighton University campus. He was heavily involved in the day-to-day operations of the restaurant. It was quite successful as long as Gibson was around to keep tabs on things; when other opportunities arose a few years later that pulled him away from Omaha, he found it difficult to find reliable people who would maintain his standards of service, and he closed the restaurant after ten years in business.

Jobs in baseball were harder to come by. On his last day with the Cardinals in 1975, general manager Bing Devine (who had been rehired by Busch in December 1967) had spoken to him about an unspecified position in the organization. Gibson begged off, telling Devine he wanted to rest and clear his head before making any decisions about his future. The subject was never raised with him again. “I’ve often thought how different my life would have been if I had said ‘yes’ that day,” he said later.

In 1981 his friend and former teammate Joe Torre hired him as an “attitude coach” for the New York Mets. Torre and his coaches were fired after the 1981 season. Gibson had some conversations with the owners of the Louisville Cardinals about managing that team in 1982. He said that opportunity was blocked by the St. Louis front office, although he never knew why.

Torre was hired to manage the Atlanta Braves in 1982, and Gibson joined him as pitching coach. After winning the National League West in 1982, the Braves began to decline and Torre and his staff were fired after the 1984 season. Gibson contacted a number of organizations about coaching vacancies in the years that followed, to no avail. Several years later, he had discussions with his friend, National League President Bill White, about a job as supervisor of umpires; that job never materialized either.

At the time his autobiography, Stranger to the Game, was published in 1994, Gibson was convinced his reputation for being outspoken and difficult to get along with was being held against him. He also believed some people in the Cardinals’ organization may had been quietly working behind the scenes to keep him out of the game. One contributing factor may have been an incident at the Baseball Hall of Fame. Gibson, elected to the Hall in 1981 in his first year of eligibility, gave a nonscripted acceptance speech and inadvertently forgot to thank Busch, Devine, and others in the Cardinals’ organization. Gibson was horrified when informed later about the oversight and, although he immediately contacted Busch to explain and apologize, he wondered if his breach of etiquette wasn’t partly responsible for the difficulties he had finding a job in baseball. A disillusioned Gibson noted in his autobiography, “It baffles me … that baseball would feel so antagonistic toward me as to keep me out of its ranks when all I ever did was try to play it to the best of my ability.”

In 1990 Gibson had a brief flirtation with a group of investors, including Donald Trump, who were interested in forming a rival baseball league, but the endeavor folded when the investors realized they could never compete with the newly found riches major-league teams enjoyed as a result of Major League Baseball’s new broadcasting contract with ESPN.

Gibson had one last fling as an on-field coach. Joe Torre was hired to manage the Cardinals in 1990, and in 1995 Gibson came aboard as pitching coach. Torre was fired in mid-June, however, and Gibson was out at the end of the season. He later served as a special instructor for the Cardinals for several years.

In retirement, Gibson continued to live in suburban Omaha. He was on the Board of Directors of the Baseball Assistance Team (B.A.T.), an organization that provides aid to old ballplayers who are down on their luck. In addition to his other honors, he was named to MLB’s All-Century Team. He was the first inductee into the Creighton University Athletics Hall of Fame (1968), and the university created the Robert Gibson Scholarship in 2005 in honor of his career achievements. He was inducted into the Missouri Valley Conference Hall of Fame in 2005 and the Omaha Sports Hall of Fame in 2007.

In 2009 he and fellow Hall of Famer Reggie Jackson teamed with Gibson biographer Lonnie Wheeler to offer their perspectives on the battle between pitchers and batters in Sixty Feet, Six Inches: A Hall of Fame Pitcher & a Hall of Fame Hitter Talk About How the Game Is Played (Doubleday).

After fighting pancreatic cancer for more than a year, Gibson died at the age of 84 on October 2, 2020, just a month after his longtime Cardinals teammate and fellow Hall of Famer Lou Brock.

An earlier version of this biography is included in SABR’s “Drama and Pride in the Gateway City: The 1964 St. Louis Cardinals” (University of Nebraska Press, 2013), edited by John Harry Stahl and Bill Nowlin.

Sources

Angell, Roger, “Distance,” in Late Innings: A Baseball Classic From the Best Writer in the Game, New York: Fireside Books, 1982.

Flood, Curt, with Richard Carter, The Way It Is, New York: Pocket Books, 1972

Halberstam, David, October 1964, New York: Villard Books, 1994.

Gibson, Bob, with Lonnie Wheeler, Stranger To The Game: The Autobiography of Bob Gibson, New York: Penguin Books, 1994.

Gibson, Bob, and Reggie Jackson, with Lonnie Wheeler, Sixty Feet, Six Inches: A Hall of Fame Pitcher and a Hall of Fame Hitter Talk About How the Game Is Played, New York: Doubleday, 2009.

Kahn, Roger, The Head Game: Baseball Seen From the Pitcher’s Mound, San Diego: Harcourt Press, 2000.

McCarver, Tim, with Ray Robinson, Oh, Baby I Love It!, New York: Dell Publishing, 1987.

MacCarl, Neil, “Pilots Tab Nelson ‘Most Dangerous,’” The Sporting News, September 10, 1958, p. 29.

Weber, Al, “Cards’ Big Four of Future Polishing at Rochester,” The Sporting News, July 16, 1958, p. 33.

Notes

1 Bob Gibson with Lonnie Wheeler, Stranger To The Game: The Autobiography of Bob Gibson, New York: Penguin Books, 1994, p.101. Unless otherwise noted, the shorter quotes in this text are taken from the same source.

2 Tim McCarver with Ray Robinson, Oh, Baby I Love It!, New York: Dell Publishing, 1987, pp. 58-59.

3 Gibson and Wheeler, pp. 166-167.

4 He did not care for the name “Pack,” and later had it legally dropped.

5 Gibson and Wheeler, pp. 10-11.

6 Information about Gibson’s basketball career at Creighton can be found at www.gocreighton.com

7 Gibson and Wheeler, pp. 52-53.

8 Gibson and Wheeler, p. 62.

9 Curt Flood with Richard Carter, The Way It Is, New York: Pocket Books, 1972, pp. 51-52.

10 Flood and Carter, p. 53-54.

11 Gibson and Wheeler, p. 66.

12 McCarver and Robinson, p. 61.

13 Flood and Carter, pp. 68-69.

14 Gibson and Wheeler, pp. 82-83.

15 At least one researcher argues that Gibson’s fielding ability was overstated. See John Knox’s article “The 100 Top Fielding MLB Pitchers, circa 1900 – 2008” in The Baseball Research Journal (Cleveland: SABR, Summer 2009, p. 49.)

Full Name

Pack Robert Gibson

Born

November 9, 1935 at Omaha, NE (USA)

Died

October 2, 2020 at Omaha, NE (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.