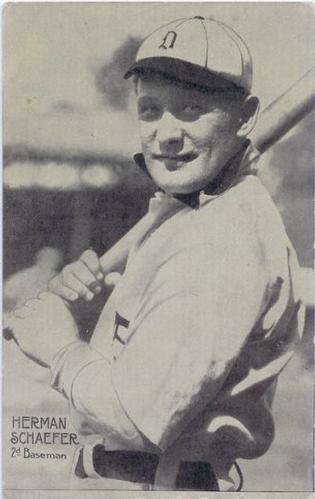

Germany Schaefer

Always willing to entertain the crowd, Germany Schaefer’s antics as a player and coach helped pave the way for later baseball clowns. An infielder with decent range and an average bat, Schaefer had impeccable timing, and more than once delighted fans with clutch performances, including legendary homers off Rube Waddell and Doc White. He gained his greatest notoriety for “stealing first base,” a maneuver that led to a rule change.

Always willing to entertain the crowd, Germany Schaefer’s antics as a player and coach helped pave the way for later baseball clowns. An infielder with decent range and an average bat, Schaefer had impeccable timing, and more than once delighted fans with clutch performances, including legendary homers off Rube Waddell and Doc White. He gained his greatest notoriety for “stealing first base,” a maneuver that led to a rule change.

Herman A. Schaefer was born to German immigrant parents in Chicago’s South Side Levee District, on February 4, 1876. The neighborhood was world-famous for prostitution and vice, including a patchwork of ethnic gangs which often served as a violent backdrop for Schaefer’s youth. Nevertheless, Schaefer had an enjoyable childhood, gravitating to the game of baseball, which he and other neighborhood kids played in sandlots and in the streets. By the time he was 18, Schaefer’s defensive skill and slugging prowess gained attention. A right-handed hitter and thrower with solid shoulders and short legs, the 5’9″ Schaefer was quick and agile on the diamond.

After a few years playing semipro ball in Chicago, Schaefer signed on with a semipro club in Sioux Falls, South Dakota, in 1898. His outstanding play with that team spurred an offer from Kansas City of the Western League, where he suited up for parts of two seasons, mostly at shortstop. In 1901, his contract was acquired by St. Paul of a new Western League, and after a solid performance he was purchased by the Chicago Cubs late in the season. He made his major league debut on October 5, 1901, and banged out three hits in five at-bats in two games.

Back with the Cubs in 1902, the 25-year old Schaefer played third base but lost his job in mid-season due to a terrible .196 batting average. He did partake in a bit of history on September 13, when he played third base in the game that featured Joe Tinker, Johnny Evers, and Frank Chance in their familiar spots in the infield together for the first time. However, after the season, the Cubs returned Schaefer to St. Paul, where he spent another season before the Saints released him in February 1904. Schaefer then signed with Seattle of the outlaw Pacific Coast League, but after the PCL reached a peace agreement with organized baseball, a dispute broke out over his services and he was ultimately assigned to Milwaukee of the American Association. In his lone season with the Brewers, Schaefer honed his defensive skills, improving his range and accuracy while also perfecting several daring baserunning plays he would later employ in the majors. One Milwaukee observer described Schaefer: “He was a well-built chap, wearing an astonishing pair of shoulders, and showed rare speed and fighting ability.”

In 1905, the struggling Detroit Tigers were in desperate need of middle infielders. Schaefer, purchased from Milwaukee, joined the team and fit in immediately, most notably with Charley O’Leary, a fellow Chicago native and infielder. The two were best friends both on and off the field, and later briefly teamed in a vaudeville act. In his first season with the Tigers, Schaefer proved his worth. “Herman Schaffer [sic], second baseman and principal prop of the Detroit infield, is one of the few ball players whose value to a team is not shown by statistics,” wrote one observer. In 1905, Schaefer led American League second basemen in putouts, while hitting .244 with nine triples.

“The Prince,” as he was often called because of his flashy showmanship on the field, always enjoyed performing in front of his hometown crowd, and on May 24, 1906, he turned in one of the most memorable games of his career. Schaefer was called on to pinch hit with two outs in the ninth, a runner on base, and his Tigers down by a run. According to teammate Davy Jones in The Glory of Their Times, Germany announced to the crowd: “Ladies and gentlemen, you are now looking at Herman Schaefer, better known as ‘Herman the Great,’ acknowledged by one and all to be the greatest pinch-hitter in the world. I am now going to hit the ball into the left field bleachers. Thank you.”

Facing Chicago’s Doc White, Schaefer proceeded to hit the first pitch into the left field bleachers for a game-winning homer. As he made his way around the diamond, Germany supposedly slid into every base, announcing his progress as if it were a horse race as he went around. “Schaefer leads at the half!” and so on. After hook-sliding into home, he popped up, doffed his cap, bowed, and said, “Ladies and Gentlemen, this concludes this afternoon’s performance. I thank you for your kind attention.” Newspaper accounts of the game confirm the dramatic baseball details but not the fanciful embellishments offered by Jones.

Once while facing Rube Waddell, one of his favorite targets for verbal abuse, Schaefer reportedly launched a long home run out of Philadelphia’s Columbia Park and razzed the left-hander as he trotted around the bases. Carrying his bat with him, Schaefer pretended it was a gun, “shooting” Rube as he moved from bag to bag. Among Schaefer’s other supposed antics: during a steady rain he once appeared at the plate wearing rubber boots and a raincoat, and he once ventured to the plate sporting a fake black mustache. In both instances, his outlandish behavior reportedly resulted in his ejection. In addition, Schaefer was a master of the hidden-ball trick, which he performed in the 1907 World Series.

Once while facing Rube Waddell, one of his favorite targets for verbal abuse, Schaefer reportedly launched a long home run out of Philadelphia’s Columbia Park and razzed the left-hander as he trotted around the bases. Carrying his bat with him, Schaefer pretended it was a gun, “shooting” Rube as he moved from bag to bag. Among Schaefer’s other supposed antics: during a steady rain he once appeared at the plate wearing rubber boots and a raincoat, and he once ventured to the plate sporting a fake black mustache. In both instances, his outlandish behavior reportedly resulted in his ejection. In addition, Schaefer was a master of the hidden-ball trick, which he performed in the 1907 World Series.

Schaefer did not reserve his pranks for players alone. According to one story, umpire Jack Sheridan wandered into his favorite Chicago watering-hole for a few drinks one evening. After tilting back a few too many spirits, Sheridan fell asleep on his table, located near a drainpipe. When Schaefer ambled in and saw the ump snoozing, he hopped upstairs and knelt on the floor. Cupping his hands, he moaned into the drainpipe, “Jack Sheridan, your time has come…” After Schaefer’s creepy warning was repeated, Sheridan shook himself awake and streaked from the saloon, frightened sober. The incident so spooked Sheridan that he reportedly gave up drinking for a time. Later, Schaefer let the cat out of the bag during a game that Sheridan was working in New York. When Germany strolled to the plate, he couldn’t resist moaning, “Jack Sheridan, your time has come…” Sheridan’s neck snapped toward Schaefer, “You Dutch so-and-so, you’re out of this game!”

In 1907, Schaefer was named captain of the Tigers, whom he helped to back-to-back pennants. Germany was one of the few Tigers who befriended Ty Cobb, and he was a key figure in the Tigers late-season drive to win the 1907 pennant. Despite his popularity in Detroit, late in 1909 Schaefer was traded to Washington, for whom he played through 1914. In 1911, he enjoyed his finest offensive season, batting .334 in 125 games. During his last few years with Washington, Germany spent more time in the coach’s box than on the field. He was an accomplished sign-stealer and heckler, qualities integral to coaching during the era. One publication described Schaefer as “next to Hughie Jennings, the best grass-puller in captivity.”

On at least one occasion Schaefer stole first base. On August 4, 1911, in the bottom of the ninth, Schaefer stole second, hoping to draw a throw and allow teammate Clyde Milan, who was on third with the potential winning run, to steal home. White Sox catcher Fred Payne didn’t fall for the gambit, however, so Schaefer, now on second, took his lead toward the first-base side of the bag and promptly stole first on a subsequent pitch. Sox manager Hugh Duffy came out to argue, and while Duffy jawed with umpire Tommy Connolly, Schaefer scampered for second again. This time Schaefer got caught in a rundown, as had been his intention, and Milan dashed for home, where he was nipped to end the inning. Schaefer and his teammates then argued unsuccessfully that the play should be nullified because the White Sox had ten players on the field, although Duffy hadn’t been an active player since 1908. The official scorer credited Schaefer with only one stolen base, but he “had a perfect right to go from second back to first,” umpire Connolly insisted after the game. It has been widely reported that Schaefer also stole first base on another occasion, against Cleveland in 1908, although the details usually given are contradictory and the incident is almost certainly a fabrication.

Schaefer continued to fine tune his crazed antics as a player/coach. Umpire Silk O’Loughlin chased him from a game in Chicago on June 8, 1912 for eating popcorn in the coach’s box, and Schaefer also began to perform tricks, like tight-rope walking the foul line and using two bats to “row across the grass.” His performances were later incorporated by baseball clowns Nick Altrock and Al Schacht. While he enjoyed drawing laughter, Schaefer defended his comedic coaching as important to team success. “Is humorous coaching of value to a team? I think so. It is valuable for two reasons. It keeps our fellow in good spirits, and it sometimes distracts the opposing players…I guess Clark Griffith thinks so also, for he encourages me in my tomfoolery,” Schaefer told The Sporting News in 1912.

In a bizarre stunt in Philadelphia in October 1914, Schaefer appeared at Police Court to defend drunkards who were slated to appear before the bench that day. Reportedly, Schaefer told the judge, “Your Honor, these poor souls should not be sentenced to 30 days in jail for an offense that a millionaire would be sent home in a cab for.” Properly convinced, if not bewildered by Germany’s courtroom theatrics, the judge acquitted the drunks. Schaefer took each of the defendants to dinner and bought them a hot meal.

After a stint with Newark in the Federal League in 1915, Schaefer served as player and coach for the Yankees in 1916 and Indians in 1918. Ever the comedian, when the First World War broke out, Schaefer announced he would change his name to “Liberty” Schaefer, much as sauerkraut had been renamed “liberty cabbage.” John McGraw hired Schaefer as a scout in 1919, but when Germany was taking a train through upstate New York on May 16, he died suddenly of a hemorrhage in Saranac Lake. The 42-year old had been battling pulmonary tuberculosis. Detroit sportswriter Malcolm W. Bingay eulogized: “Germany Schaefer was the soul of baseball itself, with all its sorrows and joys, the born troubadour of the game.” A bachelor, Schaefer was survived by a sister and buried in Chicago’s Saint Boniface Cemetery.

Note

This biography originally appeared in David Jones, ed., Deadball Stars of the American League (Washington, D.C.: Potomac Books, Inc., 2006).

Sources

The author thanks Willard Dalton, a great grand nephew of Herman Schaefer, for generously sharing genealogical information about the family. For this biography, the author used a number of contemporary sources, especially those found in the subject’s file at the National Baseball Hall of Fame Library.

Full Name

William Herman Schaefer

Born

February 4, 1876 at Chicago, IL (USA)

Died

May 16, 1919 at Saranac Lake, NY (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.