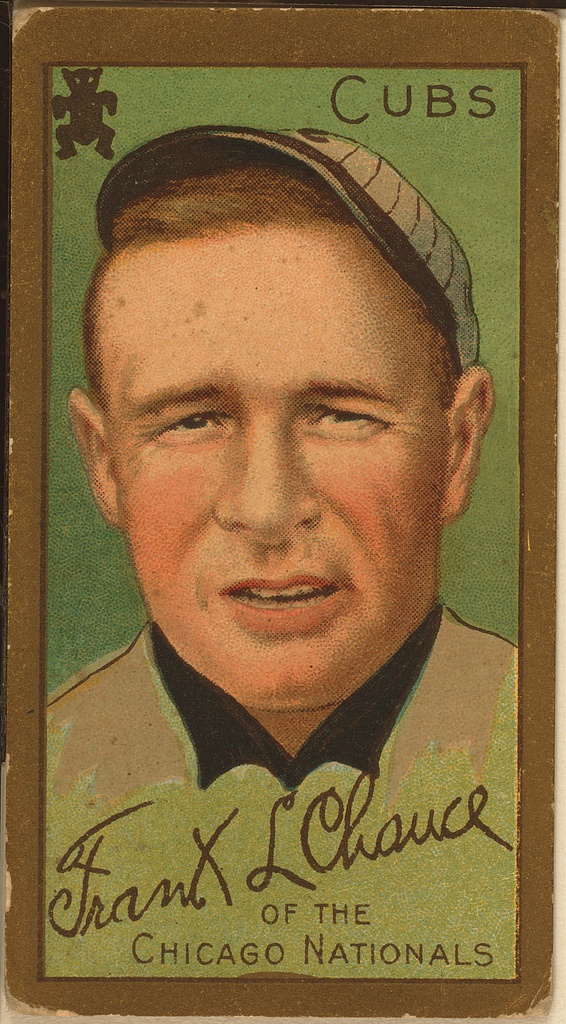

Frank Chance

Forever poetically linked to Joe Tinker and Johnny Evers by F. P. Adams’ “Baseball’s Sad Lexicon,” Frank Chance made his mark as the Cubs’ player-manager from 1905 through 1912 as part of the “Tinker-to-Evers-to-Chance” double play infield. Although not widely regarded as one of the game’s greatest fielders, Chance holds a special place in the hearts of Cub fans for his hustle and his hardnosed approach to motivating his players, not to mention guiding the much-maligned Cubs to two World Series titles in 1907 and 1908.

Forever poetically linked to Joe Tinker and Johnny Evers by F. P. Adams’ “Baseball’s Sad Lexicon,” Frank Chance made his mark as the Cubs’ player-manager from 1905 through 1912 as part of the “Tinker-to-Evers-to-Chance” double play infield. Although not widely regarded as one of the game’s greatest fielders, Chance holds a special place in the hearts of Cub fans for his hustle and his hardnosed approach to motivating his players, not to mention guiding the much-maligned Cubs to two World Series titles in 1907 and 1908.

Born in Fresno, California, on September 9, 1876, Frank Leroy Chance did not play any true form of organized baseball until his college years at the University of California, where he was pursuing an education in dentistry. It was while playing in an independent league in summer 1897, after transferring to Washington College in Irvington, California, that the right-hander caught the attention of Cubs outfielder Bill Lange. Lange convinced the Cubs management to sign Chance, sight unseen, as a backup catcher and outfielder, and he joined the team in the early spring of 1898. He made an immediate impact his rookie season, batting .279 with 32 runs scored and 14 runs batted in while playing in just 53 games in the majors (he also hit his first of only 20 career home runs, off Washington Senators pitcher Cy Swaim).

Chance continued his stint as a reserve catcher through the 1902 season, always batting slightly below .300 and never playing in over 76 games. This was due primarily to his numerous broken fingers and frequent hand injuries suffered while attempting to corral foul tipped balls. In 1903, when Johnny Kling, one of the best catchers of the era, took over the full responsibilities behind the plate, and regular first baseman Bill Hanlon unexpectedly abandoned the team, manager Frank Selee moved Chance to first base as a temporary replacement until a more suitable fielder could be found. Chance, incensed by being assigned yet another position, threatened retirement but a pay raise helped to mollify any hard feelings. Regardless, the change suited Chance as he played in over 100 games (125) and batted over .300 (.327) for the first time in his career. In addition, it was in 1903 that Chance first made his presence known on the base paths while stealing a National League leading 67 bases.

When Selee fell seriously ill in midseason 1905, Frank “Husk” Chance, so named because of his husky physical stature (6’0″, 190 lbs.), was named manager and led a strong, yet unmotivated Cubs team from National League mediocrity to a third-place finish much to the surprise of the Cubs’ faithful. Meanwhile, Chance hit .316 with 92 runs and 70 runs batted in.

The Cubs, now owned by Charles Webb Murphy, retained Chance as both manager and player for the 1906 season. It turned out to be an easy yet brilliant decision on Murphy’s part, as Chance led the Cubs to 116 wins en route to an appearance in the World Series, setting a single season win record that was unmatched until the American League’s Seattle Mariners tied it in 2001 (while playing ten additional games). Individually, Chance had a career season, batting .319 and leading the National League in both runs (103) and stolen bases (57). It is said that Frank Chance stole “baseball’s most expensive base” that season when he stole home from second base—which he had also stolen on the previous pitch—against the Cincinnati Reds to break a late-inning tie, and owner Murphy granted him ten-percent ownership in the club to show his gratitude. Chance later sold his share of the franchise for approximately $150,000.

Although the heavily favored Cubs lost the 1906 “Crosstown Classic” World Series to their Southside rivals, the Chicago White Sox, Chance would lead them back to win in 1907, defeating the Detroit Tigers four games to none; and in 1908, defeating the Tigers again, this time by the count of four games to one. In 1910, Chance’s Cubs were back in the World Series, although they lost that contest to the Philadelphia Athletics in five games. Chance fared much better as a Cubs manager than he ever did as a Cubs player, winning 100 games four out of seven full seasons (not including the 1905 season when he took over for Frank Selee) and never finishing lower than third place in the National League.

Using hardnosed tactics and downright stubbornness, Chance bowled over his opponents, and displayed an infamous lack of good sportsmanship that would make the notorious Ty Cobb blush. Chance once incited a riot at the Polo Grounds after physically assaulting opposing pitcher Joe McGinnity, and on more than one occasion tossed beer bottles at fans in Brooklyn when he felt they were being too unruly, or perhaps not unruly enough. For his fighting prowess (he spent several off-seasons working as a prizefighter), old-school boxing legends Jim Corbett and John L. Sullivan both called Chance “the greatest amateur brawler of all time.” He made outfielder Solly Hofman postpone his own wedding until the off-season lest marital bliss affect Hofman’s playing ability. It was reported that Chance would fine his own players for shaking hands with opposing players, win or lose, and had no qualms about releasing players for failing to meet his demands to the letter. Chance once remarked, “You do things my way or you meet me after the game.” Generally, his players complied, and it is no small wonder that he earned yet another nickname, “The Peerless Leader,” as he was simultaneously respected and disliked by those who played for him, with him, and against him.

Plagued by injuries for a great deal of his career, most notably injured by a barrage of beanings due to his propensity for crowding the plate, Chance’s playing career was cut relatively short. By 1911, he had virtually phased himself out of the everyday lineup, playing in only 31 games over the course of the season. He had completely lost his hearing in one ear and partially lost it in the other, causing him to unintentionally talk in an annoyingly whiny tone. As if that weren’t bad enough, he had also developed blood clots in his brain from the beanings. Incredibly, he was released by the Cubs as both a player and a manager while hospitalized for brain surgery in 1912 after a heated hospital room argument with Cubs owner Murphy over Murphy’s releasing good players to save the team money.

Making a miraculous recovery from his brain injuries, Chance spent the 1913 and 1914 seasons as a player-manager for the hapless American League New York Yankees (resigning late in the 1914 season), yet did not play in more than 12 games in either of the two seasons. He hung up his major league spikes temporarily to return home to California, where he operated an orange grove, and briefly owned and managed the Los Angeles team of the Pacific Coast League. He returned for a short stint in the major leagues in 1923 as a manager for the Boston Red Sox. The Red Sox finished dead last in the American League that year, and the following season Chance accepted the job as manager of his old crosstown nemesis, the Chicago White Sox, drawing the ire of Chicago’s Northside loyalists. However, Chance’s health took an unexpected turn for the worse, precluding him taking the job. He was ill for several months and he died on September 15, 1924.

With his .664 winning percentage as manager of the Cubs, he is clearly the franchise’s best all-time manager. For his managing career, he posted a record of 946-648 for a winning percentage of .593. As a player, Chance is the Cubs’ all-time career stolen base leader with 402; led the team in batting average in 1903, 1904, 1905 and 1907; and batted .300, with 21 hits, 11 runs, and 10 stolen bases in four World Series.

One can only wonder what kind of numbers Chance would have put up as a player had he avoided injury or had the modern training, rehabilitation and medical facilities that today’s players have at their disposal. Frank Chance was rewarded for his contributions to the game of baseball, both as a player and a manager, in 1946 when he was inducted into the National Baseball Hall of Fame in Cooperstown, New York, by the Committee on Baseball Veterans. Honored in the same class were former teammates Joe Tinker and Johnny Evers. Poetic justice.

Note: A slightly different version of this biography appeared in Tom Simon, ed., Deadball Stars of the National League (Washington, D.C.: Brassey’s Inc., 2004).

Sources

The Baseball Encyclopedia (Tenth Edition). Macmillan, 1996.

Bruce Chadwick & David M. Spindel. The Chicago Cubs: Memories and Memorabilia of the Wrigley Wonders. Abbeville, 1994.

Peter Golenbock. Wrigleyville: A Magical Tour of the Chicago Cubs. St. Martin’s Press, 1996.

Bob McConnell & David Vincent, et al. The Home Run Encyclopedia: The Who, What, and Where of Every Home Run Hit Since 1876. Macmillan, 1996.

Doug Myers. Essential Cubs: Chicago Cubs Facts, Feats, and Firsts–from the Batter’s Box to the Bullpen, to the Bleachers. McGraw-Hill, 1999.

David Nemec & Saul Wisnia, et al. Baseball: More Than 150 Years. Publications International, 1997.

Rob Neyer & Eddie Epstein. Baseball Dynasties: The Greatest Teams of All Time. Norton, 2000.

David Pietrusza, Matthew Silverman & Michael Gershman, et al. Baseball: The Biographical Encyclopedia. Total Sports, 2000.

John Thorn, et al. Total Baseball, (Seventh Edition). Total Sports, 2001.

Full Name

Frank Leroy Chance

Born

September 9, 1876 at Fresno, CA (USA)

Died

September 15, 1924 at Los Angeles, CA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.