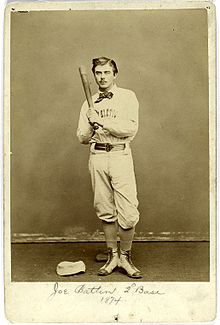

Joe Battin

Joe Battin, a 19th-century infielder, manager and umpire, was 5’ 10” tall, weighed 169 pounds, and possessed an irrepressible personality – popular but scrappy at times. A right-hander, he took pride in two accomplishments: being the highest paid player of his era and (at least by his own account) assisting Connie Mack with his start in baseball. Despite a .225 lifetime batting average in 480 big league games, he was a good fielder and even received one Hall of Fame vote in 1936, when the shrine inducted its initial class.

Joe Battin, a 19th-century infielder, manager and umpire, was 5’ 10” tall, weighed 169 pounds, and possessed an irrepressible personality – popular but scrappy at times. A right-hander, he took pride in two accomplishments: being the highest paid player of his era and (at least by his own account) assisting Connie Mack with his start in baseball. Despite a .225 lifetime batting average in 480 big league games, he was a good fielder and even received one Hall of Fame vote in 1936, when the shrine inducted its initial class.

Joseph V. Battin was born on November 11, 1853, in West Bradford, Chester County, Pennsylvania. He was the only child of Joshua and Hannah (Pierce) Battin. His father was a farmer. By the time he was seven, Joe was living with his maternal aunt, Lydia Pierce, and her husband, James. Joe’s first job was a short stint as a Civil War drummer boy, only to be kicked out because he was just 10 years old. Battin learned the bricklaying trade during his early teen years and had no trouble finding work, although he was increasingly interested in playing baseball. By age 16, he was with West Chester’s Brandywine Baseball Club, a semi-pro team that played top-flight competition in the Delaware Valley. According to the Daily Local News, “his employer [who] did not like his employee to quit work to play ball, said: ‘Joe, you can do one of two things, either play ball or lay bricks, which will you do?” His reply was ‘I’ll play ball.”1

Battin made his major-league debut as a 17-year-old with the Cleveland Forest Citys of the National Association on August 11, 1871, against the Ft. Wayne, Indiana, Kekiongas. He was 0-for-3 with a walk and a putout in right field. The Cleveland Plain Dealer called the 15-3 loss “almost the sickliest game on record…probably without exception the worst played by the club in two years.”2

In 1873, Battin played in Easton, Pennsylvania for what author Paul Batesel described as a powerful semi-pro team – it sent several men to the majors. 3 On July 4, he played third base, batted leadoff, and scored five runs for the amateur Easton team in a 39-5 rout of a club called Nameless. One game account noted, “Battin did finely at third,” posting four putouts and five assists. 4

One day in 1873, Battin was laying bricks on a scaffold when Hicks Hayhurst, president of the Philadelphia Athletics, came along and asked him if he would like to play the following season with the club. Battin accepted the offer and agreed to take $150 in advance money and a salary of $1,000 for the season.5 Battin played his second major league game in 1873 with the Athletics, going 3-for-5 with four runs, two RBIs, and a walk. He had one putout, one assist, and an error in the field. Unfortunately, there is no record of the date or Philadelphia’s opponent.

Battin appeared in 51 games for Philadelphia in 1874, batting .230. According to one 1890 account, Battin “held down second base… coming into general favor at once.”6 He was a member of the Athletics club that toured England and Ireland with Al Spalding’s Boston squad in 1874; each team won eight games and each player earned a $15,000 share of the gate receipts. His roommate during the tour was future Hall of Fame member Cap Anson. Battin had introduced Anson to his future wife, Virginia “Jennie” Feigel of Philadelphia. He was also Anson’s best man at their 1876 wedding.7 It was during this period that Battin became the highest salaried player in baseball, earning $700 a month.8 He also umpired his first game on May 22, 1874, a National Association contest between the Baltimore Canaries and the Hartford Dark Blues, a 9-7 Baltimore victory.9

Battin signed with the St. Louis Brown Stockings of the National Association in 1875 and hit .250 in 67 games. On September 11, he “played third as well as he ever attended second” in a 6-0 win over Hartford. 10 He also singled and scoring a run. On November 7, in a writeup of what appears to have been some form of unofficial postseason competition, the St. Louis Globe-Democrat said he “brought down the house” by taking a hot liner from Oram’s bat in a 10-8 victory over the Picked Nine.11

Battin returned to St. Louis, now in the National League, in 1876. He had his best year with the bat (.300, 34 runs, 46 RBIs in 64 games). He was also the league’s leading fielder at third base, though his .867 mark was a sign how much fielding would advance in years to come. On July 15, Battin was an important part of George Bradley’s no-hitter, the first in major league history, a 2-0 St. Louis win over Hartford. With two outs, after mishandling Jack Burdock’s grounder at third, Battin “made a fantastic stop” of a hot liner by Dick Higham. He then doubled Burdock off first to end the game.12

On May 1, 1877, Battin played in what Henry Chadwick called “The Grandest Game Ever Played.” It was a 15-inning scoreless tie between the St. Louis Brown Stockings and the independent Star Club of Syracuse, featuring “heavy batting [despite a lack of runs], splendid fielding, and universal brilliancy of play.”13 Battin was hitless against pitcher Harry McCormick with two putouts and an assist at third base.

A few months later, though, Battin’s time in the NL ended under a cloud. According to Paul Batesel, “On August 25, 1877, he [Battin] and Joe Blong were named as gamblers and ‘willing partners’ in a St. Louis loss and as a result were ‘eased’ out of the league.”14

In 1878, Battin played in the International Association. He first performed for the New Bedford/New Haven/Hartford club and later for Lynn/Worcester. On June 28, the Worcester Daily Spy noted that “Battin, the new third baseman of the Worcesters, made a fine beginning [including two hits], and everybody was pleased with his work.”15

By the end of August, Battin had been elected team captain. He continued to play in the International Association in 1879, first with Utica and, as of mid-August, with Springfield. On June 10, the Springfield Republican noted that “The Uticas played a poor game at Holyoke yesterday, Battin [2-for-4, two walks] and Dolan being however brilliant exceptions and their playing securing frequent applause.”16

The available records do not show where Battin played in 1880, if he did at all. Battin returned to Philadelphia with the Athletics of the Eastern Championship Association in 1881. He attracted generally positive attention from the press that year. In an 8-2 loss to the New York Metropolitans on July 19, the New York Herald noted that he stroked two hits and “picked the balls up handsomely…but his throwing to first was miserable.” 17 On August 29, in a 10-2 Philadelphia win over Baltimore, the Philadelphia Inquirer said that “Battin carried off the batting honors, stroking two hits and scoring twice.”18 According to the St. Louis Globe-Democrat, “Battin at third was one of the features of the game most admired” in a 6-3 loss to the Browns on September 3. 19

Philadelphia released Battin in mid-April 1882 and, on June 4, it was announced that he had been appointed a league umpire.20 By late August, he surfaced with the Pittsburgh Alleghenys of the American Association, where he appeared in 34 games and batted .211. On August 25, the Cincinnati Commercial Tribune reported that “Joe Battin is playing a fine game at third base for the Alleghenys.”21 He continued to play with the Alleghenys in 1883 (98 games, .214, and a league-leading .891 fielding percentage). Perhaps his best game was on July 12 when he went 5-for-5 with two runs, three doubles, and a triple in a 9-1 win against the Athletics. He managed his first game for Pittsburgh on September 10, 1883, a 12-6 loss at Cincinnati. His overall record as Pittsburgh’s interim manager in 1883 was 2-11.

Battin briefly returned to Pittsburgh in 1884 but was “laid off” and then suspended in late June, only to be hired as manager in July after Bob Ferguson was fired. 22 His managerial tenure lasted only two weeks even though the team played almost .500 ball (6-7) under him. Unfortunately, he was axed again on August 7, although team directors refused to say why. The press speculated that it was because Battin was very popular with the members of the club and player dissatisfaction with his release caused a 6-0 loss to Brooklyn. The Boston Herald thought it had to do with “falling off in his batting.”23 (He hit just .177 in 43 games.) Reading between the lines, it appears that the team gave less than a maximum effort. By August 10, Battin was placed on Pittsburgh’s retired list.

On August 11, he headed to Detroit and arrived two days later to replace Bill Geiss, but saw no action.24 Battin signed with the Pittsburgh club in the Union Association (the franchise had relocated from Chicago). He batted .188 in 18 games and posted a 1-5 record as manager. He also played for the Baltimore club in the UA that year (17 games, .102).

Battin spent the winter of 1884-85 in Pittsburgh. He returned to the minor leagues in 1885, first with Waterbury of the Southern New England League (40 games, .145). On July 28, the Cleveland Leader reported that “Battin is playing his usual good third base for Waterbury, but his batting is as weak as ever.”25 Shortly thereafter, he was signed as an umpire by the American Association. He also played for Cleveland of the Western League (29 games, .186) and Binghamton of the New York State League.

Battin returned to Waterbury in 1886, playing for the city’s entry in the Eastern League, the Brassmen. He hit .228 in 94 games and managed for part of the season too. That year prompted Battin’s claim that he recommended Connie Mack to Washington of the National League – which Norman Macht, Mack’s biographer, called “dubious. Battin did play against Mack in the Eastern League in 1886 and may well have had good things to say about him, but he certainly didn’t discover him and it’s a stretch to say he recommended Mack to the son of the owner of the Washington Club, who had gone to Hartford to buy some players and was subjected to a little arm-twisting to take Mack along with three others.”26

Nonetheless, it appears that Battin and Mack maintained a friendship for many years. Mack would leave tickets for Battin, and decades later, in 1933, The Akron Times-Press reported that “A few years ago, Mack came to Akron to visit Battin when he was in the hospital.”27

Ahead of the 1887 season, the Cleveland Leader remarked, “Joe Battin is one of the few players always in condition to play. He was the only man in the Waterbury club last season who played in every game, both regular and exhibition.” 28 Battin remained in Waterbury that year, hitting .321 in 54 games. In May, the Plain Dealer noted that “Joe Battin of the old Athletics and St. Louis Browns is doing good work on third for Waterbury.”29 He upheld his reputation as a durable player too; in early August, the Rochester Democrat and Chronicle noted that “Battin has played ball thirteen years and in all that time he has lost but seven games by sickness or otherwise.”30

During the 1887 season, Battin moved to Syracuse of the International Association when the Waterbury team relocated. He returned to Syracuse in 1888 (110 games, .196). That July, the Boston Herald noted that “old Joe Battin is playing a great third base.”31 He also showed his feisty side. In August, he had a fistfight with a teammate, pitcher Con Murphy, over their abilities as batsmen. Battin thought Murphy should be placed lower in the order. Murphy resented this and, according to the Plain Dealer, “hot words followed and finally Murphy called Battin a liar, whereupon the latter promptly knocked Murphy down with a blow to the nasal organ.”32

In 1889, again with Syracuse, Battin hit .167 in 107 games but led Southern New England League third basemen in fielding. According to the Evansville Courier and Press, he also offered a unique suggestion on how to increase batting: “do away with the wearing of gloves by in-fielders. He claims that many batsmen are now put out on hits that would otherwise be safe and he attributes the daring of fielders in large measure due to the use of gloves.”33

The rise of the Players’ League in 1890 gave Battin a last opportunity to play at the big-league level.34 He was with the Syracuse Stars of the American Association for 29 games, hitting .210. On May 27, Battin had four fielding opportunities at third base. One resulted in a wild throw and the others found him reacting poorly to three hot grounders which should have been fielded. He was released by Syracuse by the end of May, prompting the Philadelphia Inquirer to note “Poor Joe Battin has about reached the bottom of the ladder. He was a dandy in his day.”35 He then signed with Saginaw-Bay City of the International Association on May 31, hitting .208 in 27 games.

Battin continued to umpire in the late 1880s and early 1890s, but to increasingly bad notices. In late April 1891, the Watertown Daily Times commented on his work in the Eastern Association: “Joe Battin’s umpiring Saturday was bad.”36 The Bay City Times featured a scathing review of his work in May 1891, noting that he “really is to be pitied, he ought to be driving a street car…he does as well as his limited capabilities allow him…he has made a colossal failure of it.”37 On June 6, 1891, the Eastern Association announced that Battin had been fired.38

Battin’s work as an umpire offered him an opportunity to scout and help young players by recommending them to his acquaintances. One such situation came about in 1890 when Bill Dahlen had an outstanding season at Cobbleskill of the New York State League. His play attracted Battin’s attention, and he later recommended Dahlen to Cap Anson, who was then managing the National League’s Chicago Colts.39

In October 1892, the Trenton Evening Times reported that “Joe Battin, after twenty years on the ball field, had gone back to his old trade as a bricklayer.”40 In 1893, however, the 39-year-old Battin appeared in four games for Reading of the Pennsylvania State League. His playing career concluded the following year with 16 games for Easton (also in the Pennsylvania State League) and two for Buffalo in the Eastern League.

In 1896, the Detroit Free Press reported that Battin “has been for the last year or so connected with a St. Louis race track.”41 He also still umpired on occasion, working his final game on July 12, 1896, a 14-1 Washington win at St. Louis. That year, Battin discussed his views on umpiring with the Milwaukee Sentinel. “If you want to tackle a job that will turn your hair from the hue of the raven’s wing to an iron grey in less than a fortnight, just try umpiring in the Western League. I have never been in any sort of a jail or prison, but I think I would rather serve two years in such a place than do a turn of two weeks as the master of ceremonies in a championship game at Minneapolis, St. Paul, and a few other Western cities.”42

In 1900, Battin was employed by Homestead Steel in Pittsburgh. By 1910, he was living in West Chester, Pennsylvania, with his wife of 36 years, Kathrine, and their daughter, Annette, age 33. At the time, Joe was working as a policeman. Kathrine died in 1911.43

The 1920 census showed Battin, described as a “retired bricklayer,” living in Akron, Ohio.44 Sixteen years later, when the Baseball Hall of Fame inducted its first class, Battin received one vote. Author James Vail shed light on this curiosity. There were two different ballots in 1936. Members of the Baseball Writers Association of America (BBWAA) “were charged with selecting ‘modern’ players who appeared in the majors after 1901. A second set of electors, an Old-Timers Committee (OTC), whose 78-man composition is currently unknown (but probably consisted of the elder statesmen among the BBWAA’s active and retired membership of the era), was supposed to select five men who played primarily in the 19th century. … It was never made clear who should be eligible for either of the 1936 ballots. … The lack of forethought regarding eligibility also encouraged some electors to vote for players with relatively short big-league careers.”45

The Eagles Lodge of Akron honored Battin as its oldest member in November 1937 – but soon thereafter he fell ill with pneumonia. Joe Battin died on December 10, 1937. He is buried in Akron’s Glendale Cemetery. There were no survivors.

Acknowledgments

A special thanks to Rory Costello for his baseball knowledge and editing expertise. This biography wouldn’t have seen the light of day without his help.

This biography was reviewed by David Lippman and Rory Costello and fact-checked by Thomas Nester.

Notes

1 “Base Ball,” Daily Local News, West Chester, Pennsylvania, December 4, 1907.

2 “Base Ball: Another Ku-Klux Outrage: The Championship Contest,” Cleveland Plain Dealer, August 18, 1871, 3.

3 Paul Batesel, Players and Teams of the National Association, 1871-1875, Jefferson, North Carolina, McFarland & Company. 2012: 13, 19.

4 “The Amateur Arena,” Brooklyn Daily Eagle, July 8, 1873, 4.

5 “Old Joe Battin, “ Saginaw Evening News, June 14, 1890, 11.

6 Ibid.

77 “Akronite, Started Connie Mack on Way to Major League,” Akron (Ohio) Times-Press, September 25, 1931, 23. Battin Hall of Fame Clipping File.

8 Ibid.

9 Joe Battin page, Baseball-reference.com.

10 “Nine Of ’Em,” St. Louis Globe-Democrat, September 12, 1875, 6.

11 “Pretty Work,” St. Louis Globe-Democrat, November 8, 1875, 8.

12 David Arcidiacono, Major League Baseball in Gilded Age Connecticut, Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, 2010: 167

13 Lloyd Johnson, “Long 1877 Duel of Zeros Put Syracuse on Map: The Grandest Game,” SABR Research Journal Archive.

14 Batesel, Players and Teams of the National Association, 1871-1875, 22.

15 “The Ball Field,” Worcester Daily Spy, June 28, 1878, 4.

16 “Sporting Matters: Base Ball,” Springfield Republican, June 11, 1879, 5.

17 “Base-ball: The Metropolitans Gain An Easy Victory Over The Athletics,” New York Herald, July 20, 1881, 5.

18 “Ten To Two,” Philadelphia Inquirer, August, 30, 1881, 2.

19 “Beaten By The Browns,,” St. Louis Globe-Democrat, , September4, 1881, 3.

20 “Base Ball,” The Metropolitans Gain An Easy Victory Over The Athletics, New York Herald, July 20, 1881, 5.

21 “The Home Stretch in the American Championship Race,” Cincinnati Commercial Tribune, August 25, 1882, 8.

22 “Battin Laid Off,” The Pittsburgh Press, June 23, 1884, 1.

23 “Joe Battin Released,” The Boston Herald, August 7, 1884, 2.

24 1884 Detroit Wolverines Regular Season Roster, Retrosheet.org.

25 “Base Ball Notes,” Cleveland Leader, July 28, 1885, 2

26 “Norman L. Macht, The Grand Old Man of Baseball: Connie Mack in His Final Years, 1932-1956, Lincoln, Nebraska: University of Nebraska Press, 2015.

27 “Joe Battin, 80-Year-Old Akronite, Started Connie Mack In Baseball,” Akron Times-Press, Akron, Ohio, September 25, 1933, Joe Battin Hall of Fame Clipping File.

28 “The World of Sport,” Cleveland Leader, February 27, 1887, 12.

29 “Veterans Of The League,” Cleveland Plain Dealer, May 22, 1887, 7

30 “Tips And Tosses,” Rochester (New York) Democrat and Chronicle, August 4, 1887, 6.

31 “Ball And Bat,” Boston Herald, July 23, 1888, 8

32 “Base Ball Notes,” Cleveland Plain Dealer, August 18, 1888, 6.

# “Tips And Tosses,” Rochester Democrat and Chronicle, August 4, 1887, 6.

33 “Base Ball, Evansville (Indiana) Courier and Press, May 8, 1889,1.

34 Batesel, Players and Teams of the National Association, 1871-1875, 23.

35 “Notes Of The Diamond Fields,” Philadelphia Inquirer, May 30, 1890, 2.

36 “Many Games,” Watertown (New York) Daily Times m April 27, 1891, 5.

37 “Old Joe Battin: Not A Howling Success As An Umpire,” Bay City (Michigan) Times, May 1, 1891, 4.

38 “Joe Battin Released,” Democrat and Chronicle, Rochester, NY, June 6, 1891, 9.

39 Ibid.

40 “General Sporting Notes,” Trenton (New Jersey) Evening Times, October 23, 1892, 3.

41 “Baseball Brevities,” Detroit Free Press, December 17, 1896, 6.

42 “Decline of Canoeing,” The Milwaukee Sentinel, December 29, 1896, 2.

43 U.S. Find A Grave Index, 1600s-Current.

44 Batesel, Players and Teams of the National Association, 1871-1875, 23.

45 James Vail, Outrageous Fortune, Jefferson, North Carolina, McFarland & Company, 2001: 18-20.

Full Name

Joseph V. Battin

Born

November 11, 1853 at West Bradford, PA (USA)

Died

December 10, 1937 at Akron, OH (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.