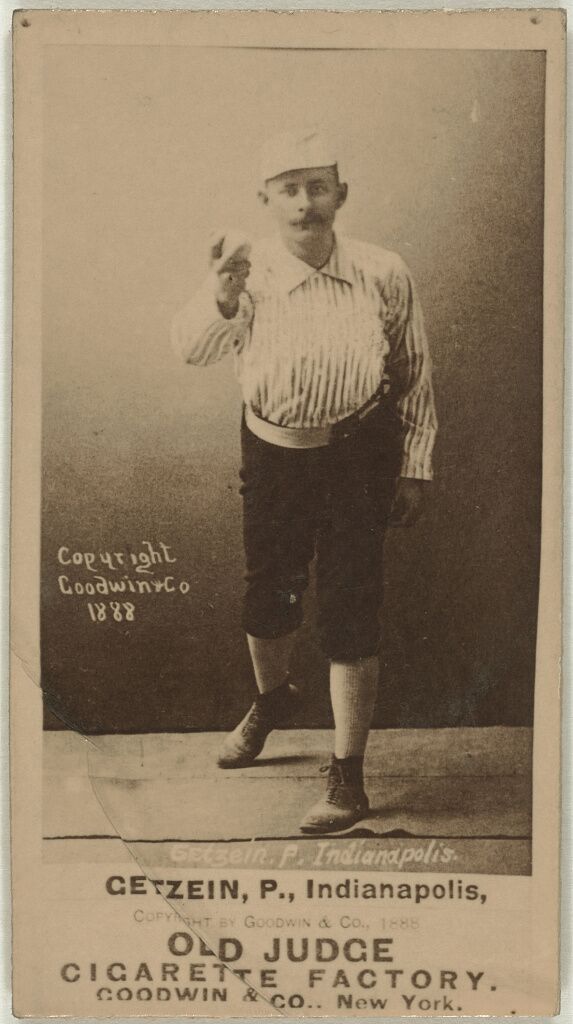

Pretzels Getzien

In addition to being a pretty good pitcher and the first German-born player in the major leagues, Charles Getzien had one of the better nicknames in nineteenth-century baseball: Pretzels or Pretzel Twirler. Before becoming a Boston Beaneater, Getzien gained prominence as a star for the Detroit Wolverines of the National League, winning a championship with them in 1887. Getzien’s surname was constantly misspelled (most commonly as “Getzein”) by the press, but at least the reporters got “Pretzels” right.

In addition to being a pretty good pitcher and the first German-born player in the major leagues, Charles Getzien had one of the better nicknames in nineteenth-century baseball: Pretzels or Pretzel Twirler. Before becoming a Boston Beaneater, Getzien gained prominence as a star for the Detroit Wolverines of the National League, winning a championship with them in 1887. Getzien’s surname was constantly misspelled (most commonly as “Getzein”) by the press, but at least the reporters got “Pretzels” right.

Charles Friedrich Ludwig Getzien was born on February 14, 1864, to Carl and Wilhelmine Getzien. The Getziens had lived in the small north Prussian village of Kletzin1 (today this is northeastern Germany) before coming to the United States. Both Carl and Wilhelmine (known to the family as Mina) were born in 1836 in Prussia. The family emigrated from Germany when Charles was a boy, although the exact year is unknown. According to the 1880 US Census, the family was living at 173 Cornell Street in Chicago.2 Carl (he had changed his name to Charles upon arrival in America) was working as a day laborer. Mina stayed at home to care for their three children, Charles, aged 16 and employed as an errand boy; daughter Mina, 12, and Sophia, 8. Sophia was listed as being born in Illinois.

Getzien’s professional baseball career started with the Grand Rapids (Michigan) Baseball Club in 1883. A right-handed pitcher, he was 14-12 in his inaugural season. A year later he was the pitching star of the team, producing a won-lost record of 27-4,3 and that led him to sign with the Detroit Wolverines later in the 1884 season. On August 13, 1884, Getzien made his major-league debut. Facing the Cleveland Blues, Getzien struck out six of the first eight batters he faced, but picked up 1-0 loss, falling to a former Grand Rapids teammate, John Henry, who was also making his NL debut. Cleveland scored an unearned run in the fifth inning when third baseman Joe Farrell muffed a popup.4 Getzien came up short in his first eight decisions before finally gaining a victory on September 20 for the last-place Wolverines. Another of his Grand Rapids teammates was Edward Gastfield. Gastfield, a catcher, who also started in the Chicago City League and became Getzien’s batterymate with Detroit.

Getzien earned the nickname Pretzels because of his “puzzling twisters.”5 According to Sporting Life, batters “describe the course of the ball from his hand to their bats as a ‘pretzel curve.’ In delivering his ‘pretzels’ ‘Getz’ faces third base with one foot in either corner of the lower end of the box. Bending the left knee slightly, he draws his right arm well back.Then, straightening up quickly, he slides the left foot forward with a characteristic little skip, and, bringing his arm around with a swift overhand swing, drives the ball in at a lively pace.”6

The high point of Getzien’s 1884 season occurred on October 1, when the 20-year-old hurler pitched a six-inning no-hit game.7 In a game played at Detroit’s Recreation Park, Getzien struck out 10 of the 19 batters he faced. He helped his own cause with a single in the seventh before rain forced the game to be called. In the second inning, Getzien walked Tom Lynch and Charlie Ferguson reached on an error. Lynch was erased on a double play, giving Ferguson, the Quakers’ pitcher, “the honor of having been left on base.”8 Detroit won the contest, 1-0. Overall, Getzien’s rookie season was a success. In 147⅓ innings, he allowed 118 hits while striking out 107. Although his record was 5-12 (Detroit’s record was 28-84), Getzien’s earned-run average was 1.95, third lowest in the National League.9

Getzien continued with the Wolverines for the next four seasons. In 1885 he completed all 37 of his starts, pitching 330 innings, but his ERA shot up to 3.03. He won only 12 games and lost 25. The next season, 1886, he posted an identical 3.03 ERA while winning 30 games and losing 11. Only 111 of the 222 runs he allowed were earned. In an article in September the Detroit Free Press detailed the success of Getzien’s pretzel curves. Under the subheadline of “Our Sturdy German Twirler Does Good Work at Kansas City,” readers discovered that “The Pretzel is all right. He went into the box to-day and pitched one of his finest, his curves circling around in the form of the delicious pastry from which Getz takes his sobriquet; all of which brings to the front the pleasing fact that the pot of Grand Rapids will do good work for the Detroit Club for the remainder of the season.”10

In an article in 1915, Baseball Magazine described an 1886 game between the Wolverines and Washington Nationals:

“The Nationals got onto Getzein in the fourth inning and batted him all over the field. In the fifth inning they kept up the slugging until Getzein said he was ill, and Manager [Ned] Hanlon wanted the Nationals to allow Getzein to retire, claiming that he was too sick to play. Phil] Baker, captaining the home club, said he would call a doctor and have him examine Getzein, and if the latter was really sick he would probably allow the change to be made. Dr. Bond, who happened to be present, was called on, and he examined the pitcher, while the crowd guyed Getzein terribly. The doctor announced that he did not consider Getzein sick, only discouraged at the pounding he had received, and that he would be able to finish the game.”11

In 1887 Getzien led the National League with a .690 winning percentage (29-13) with 41 complete games. He tied for the league lead (with Egyptian Healy) by yielding 24 home runs. At the beginning of September, Sporting Life wrote, “A surprise is in store for Charlie Getzien. His magnificent work for the club has excited the admiration of Detroiters to a high degree and they intend to express their feelings in a substantial manner. … An elegant two hundred dollar gold watch and chain [was] purchased, which will be presented to the sturdy twirler.”12 Another example of his prowess on the mound came in a game at Sportsman’s Park against the St. Louis Browns of the American Association. This was Game 10 of the postseason series between the two teams. Getzien toyed with another no-hitter. According to the Detroit Free Press, “Up to and including the eighth inning only twenty-seven men went to the bat and not a clean hit had been scored. Not till the ninth did the world beaters succeed in getting a hit, and then they failed to score the much desired run.”13 A crowd of 10,000 “seemed to enjoy the way in which the Browns were larruped”14 as Getzien and the Wolverines defeated the Browns, 9-0, enroute to winning the series, 10 games to 5.

Getzien’s career with the Wolverines ended after the 1888 season. He pitched in 46 games, winning 19 and losing 25. Pete Conway became the ace of the pitching staff. Getzien posted a career-best 202 strikeouts, but the right-hander, now 24 years old, served up a career-high 411 hits in 404 innings. Stories appeared in the newspapers about a possible feud between Getzien and Wolverines manager Bill Watkins. After he gave up 21 hits to the Boston Beaneaters in a game in June, Sporting Life suggested that he may have lost his desire to pitch:

The Getzein episode makes Detroiters weary. The Bostons have no license to make 21 hits off the Pretzel when he pitches his game. Either he was not in condition to pitch or he didn’t try to. If the former was the case he is entitled to sympathy. If the latter, and he repeated his performance against the Kansas Citys a few years ago, when he deliberately tossed the balls to the plate and permitted the Cowboys to make 13 runs in one inning, why no one here [in Detroit] would mourn much if he was fined to the limit. What the merits of his quarrel with Watkins are of course are not known here. But Getzein is inclined to be very free with his tongue. Considering his fine treatment here it is time for him to get over his childish humors and do the best he knows how whenever called on.15

In any event, the so-called childish and free-tongued Getzien parted ways with Detroit before the next season began. He was sold to the Indianapolis Hoosiers on March 5, 1889. The Free Press predicted, “When Getz loses his head among the Hoosiers, a circus with six rings will ensue.”16

Two months before the sale, on January 17, 1889, Getzien married Rose Dibble of Grand Rapids, Michigan. She was the daughter of John and Lottie Dibble. The new couple had been living in Grand Rapids at the time of the marriage. In five seasons with the Wolverines, Getzien had pitched in 186 games, starting 185 of them and pitching 182 complete games. With the Hoosiers, he pitched in 45 games in 1889, starting all but one, but completed only 36. His earned-run average was 4.54. (The National League average was 4.02.) The Hoosiers ended the campaign in seventh place, 28 games behind the New York Giants, and 16 games under .500. The Indianapolis team folded after the 1889 season, and its players were placed “under league control.”17

The Boston Beaneaters were the next club to sign Getzien, adding him to their roster on March 22, 1890. According to Sporting Life, “The Boston triumvirs got tired of negotiating with Detroit for Pitcher [Frank] Knauss, and settled the question by signing Getzein, late of Indianapolis.”18 Getzien put together a 10-game winning streak that season for the Beaneaters and had a 23-17 record. He shared the starting rotation with rookie sensation Kid Nichols and veteran John Clarkson. The trio won all of fifth-place Boston’s 76 wins that season.

The next season, Getzien lost his spot in the Beaneaters’ rotation, and Boston released the 27-year-old on July 16, 1891. He signed with the Cleveland Spiders in August and pitched in one game for them, allowing nine runs (eight earned) on 12 hits. He gave up one home run and four walks in the loss.

In 1892 Getzien began the season with the St. Louis Browns. He appeared in 13 games, pitching 108 innings. His control was gone. He allowed 159 hits and 31 walks, threw four wild pitches, and hit six batters. Getzien played his final major-league game on July 19. His record that season was a dismal 5-8, with an ERA of 5.67. In nine seasons in the National League, Getzien won 145 games and lost 139. He pitched 2,539 innings in 296 games, and finished his career with 277 complete games. Pretzels Getzien was out of major-league baseball before he celebrated his 29th birthday.

Getzien became a naturalized US citizen on October 12, 1892.19 In 1894 Sporting Life reported, “‘Pretzel’ Getzein, the old League pitcher, is playing first base for a Chicago City League team.”20 He was still just 30 years old, but he never made it back to the National League.

After his playing days were over, Getzien and his wife moved to Chicago. According to the 1900 Census, he was working as an assistant grain-elevator inspector.21 Census documents claim that he had come to the United States in 1865. Ten years later, according to the 1910 Census, Charlie and Rose had a nephew, Fred, living with them.22 His immigration date was now listed as 1866, and he was still employed as an inspector of grain elevators in Chicago. By 1920, Getzien was now an “Inspector for the Board of Trade.”23 Some time after this, he took a job as a typesetter with the Chicago Tribune.24

Charles Getzien suffered a heart attack in 1932, at the age of 68, and died shortly thereafter, on June 19. He was buried at Concordia Cemetery in Forest Park, Illinois. His 145 wins still are a record for a pitcher born in Germany.

Sources

In addition to the sources mentioned in the notes, the author consulted baseball-reference.com and retrosheet.org.

Notes

1 As of December 31, 2015, the population of Kletzin was 809. See “Bevölkerungsstand der Kreise, Ämter und Gemeinden in Mecklenburg-Vorpommern 31.12.2015”. Statistisches Amt Mecklenburg-Vorpommern (in German), July 2016.

2 Year:1880; Census Place: Chicago, Cook, Illinois; Roll: 196; Family History Film: 1254196; Page: 211A; Enumeration District: 142; Image: 0062.

3 https://baseball-reference.com/bullpen/Charlie_Getzien.

4 “Sporting Matters: Detroit’s Weak Batting Team Shut Out by the Cleveland Team,” Detroit Free Press, August 14, 1884: 3.

5 “Notes and Comments: Chas. H. Getzein,” Sporting Life, November 2, 1887: 3.

6 Ibid.

7 In 1991 major-league baseball clarified its definition of a no-hitter as “a game in which a pitcher, or pitchers, gives up no hits while pitching at least nine innings. A pitcher may give up a run or runs so long as he pitches nine innings or more and does not give up a hit.” Before this clarification, Getzien’s feat was considered a no-hitter.

8 “Sporting Matters: Getzien and Gastfield, With a Little Aid, Play a Wonderful Game,” Detroit Free Press, October 2, 1884: 7.

9 Old Hoss Radbourn led the NL with an ERA of 1.38.

10 “Getzien Goes In: Our Sturdy German Twirler Does Good Work at Kansas City,” Detroit Free Press, September 15, 1886: 8.

11 Wm. A. Phelon, “Baseball Customs Past and Present,” Baseball Magazine, October 1915: 56.

12 “Getzien in Luck,” Sporting Life, September 3, 1887: 1.

13 “The Browns Whitewashed: Getzien Holds the World Beaters Down to Three Actual Hits,” Detroit Free Press, October 17, 1887: 5.

14 Ibid.

15 “Detroit Speculations,” Sporting Life, June 20, 1888: 1.

16 “Sporting Notes,” Detroit Free Press, March 12, 1889: 3.

17 “Transactions,” https://baseball-reference.com/players/g/getzich01.shtml.

18 “Notes and Gossip,” Sporting Life, April 5, 1890: 3.

19 Ancestry.com. Accessed January 18, 2017.

20 “Editorial Views, Notes, Comment,” Sporting Life, May 19, 1894: 3.

21 Census document found on ancestry.com. Year: 1900; Census Place: Chicago Ward 15, Cook, Illinois; Roll: 262; Page: 5B; Enumeration District: 0429; FHL microfilm: 1240262.

22 Census document found on ancestry.com. Year: 1910; Census Place: Chicago Ward 15, Cook, Illinois; Roll: T624_257; Page: 16B; Enumeration District: 0724; FHL microfilm: 1374270.

23 Census document found on Ancestry.com. Year: 1920; Census Place: Chicago Ward 15, Cook (Chicago), Illinois; Roll: T625_324; Page: 2A; Enumeration District: 873; Image: 813.

Full Name

Charles H. Getzien

Born

February 14, 1864 at , (Germany)

Died

June 19, 1932 at Chicago, IL (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.