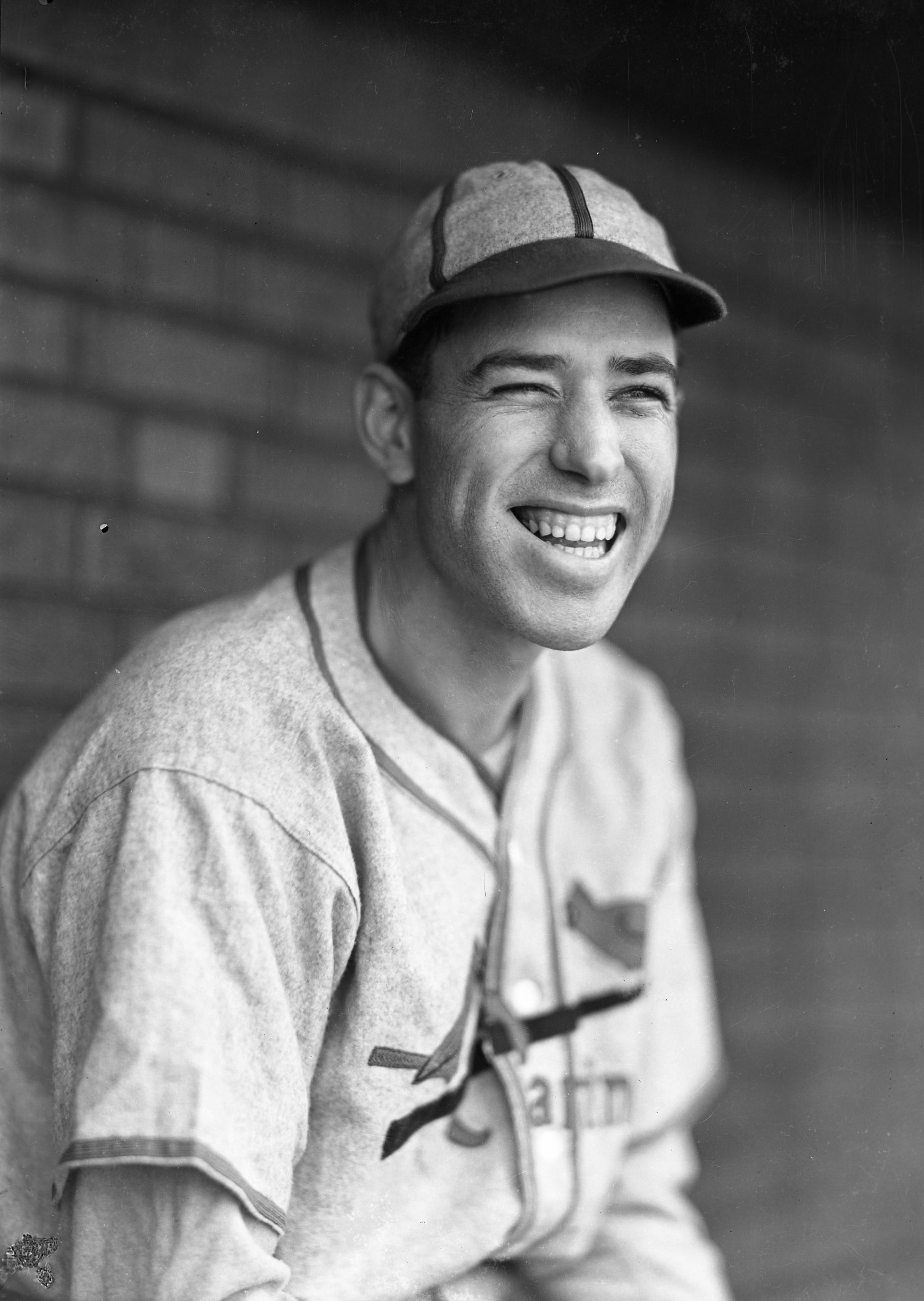

Paul Dean

As a rookie in the season that he turned 21, Paul Dean threw a no-hitter and helped lead the St. Louis Cardinals to the 1934 National League pennant. He then won two games to help the Cardinals win the World Series that year.

As a rookie in the season that he turned 21, Paul Dean threw a no-hitter and helped lead the St. Louis Cardinals to the 1934 National League pennant. He then won two games to help the Cardinals win the World Series that year.

The younger and less talkative brother of Dizzy Dean, Paul Dee “Daffy” Dean was born on August 14, 1913,1 to sharecroppers Albert Monroe “Ab” Dean and Alma Nelson Dean in Lucas, Logan County, Arkansas. Albert and Alma had five children, two of whom, Charles and Sarah May, died in infancy. Paul had two older brothers, Elmer, born in 1908, and Jay Hanna — to be known later as Dizzy — in 1910. Alma contracted tuberculosis and died in 1918, leaving Ab with three young sons. He later remarried.

The Dean family moved to Chickalah, Arkansas, then to Spaulding, Oklahoma, migrating to where they could find work. Their best annual profit from cotton-picking and sharecropping came to $155 in 1923.2

The sons learned baseball from their father, once a semipro ballplayer, but most who knew Alma said that the Dean brothers inherited much of their athletic ability from their mother, known as a “superb girl athlete with natural ability.”3

The Deans fashioned their baseballs out of yarn or socks wound around a rock, or tape around an apple core, and used an old broom or hoe handle for a bat. Not able to afford shoes, they played barefooted most of the time. They strengthened their arms and sharpened their aim by throwing at squirrels while working in the fields. Paul could usually pick about 500 pounds of cotton a day. Jay (Dizzy) never reached 400, and their dad usually did only 200 pounds, because he had to keep checking on Jay.4

The boys usually stayed home to work, and attended school sporadically. They made sure to go to class on Fridays, however, to play in the weekly baseball games, where Jay and Paul began to shine. At 12, Paul was the biggest boy in his class.

An often-told story relates a time when Elmer became separated from his father and brothers when they were driving in two vehicles. Driving the second vehicle, Elmer was cut off from the others by a long freight train. He was not reunited with his family until a couple of years later when he recognized his brothers in pictures in a Dallas newspaper.

At first Paul played shortstop and Dizzy pitched for a San Antonio semipro team, until Jay signed with the Cards. One day Paul came in to pitch when the regular pitcher was knocked out of the game. He stayed a pitcher from then on.5

At 16 Paul made a strong impression with an industrial team in San Antonio in 1930. After a tip from Jay, now called Dizzy, Don Curtis, a scout for the Cardinals, signed Paul to play for the Houston Buffs in the Cardinal farm system. Paul showed similarities to his older brother, but soon distinguished himself as “a serious youngster and not at all given to the horse-play” that characterized his brother.6

Paul moved quickly on to Columbus of the American Association, then spent the majority of his first year with Springfield of the Western Association. Promoted to Columbus in 1931, he pitched a no-hit game and led the league with 169 strikeouts.

Now standing 6-feet-3 (an inch taller than Dizzy) and weighing 189 pounds, the right-hander began to dominate at Columbus in 1933, winning 22 games, including another no-hitter, while losing seven. He placed third in the MVP voting for the American Association.

Cardinal fans anxiously awaited “Dizzy the Younger.”7 Cardinals manager Frankie Frisch said Paul could throw the “damnedest, heaviest sinker you ever saw,” adding, “When a batter hit one of those pitches, his hands stung as painfully in July as if he had swung an icicle in December.”8 The elder brother Dean made a famous brag at the beginning of the season that he and Paul would win a total of 45 games that year.9

At Dizzy’s insistence, Paul held out for a better salary before ever pitching for the Cardinals: “If Paul don’t get it, he’s goin’ back to Houston and work in a mill for some real money.”10 He said Paul would pitch for nothing until he won at least 15 games, then get $500 per win. General manager Branch Rickey threatened to charge Paul for postage if he continued to send back contracts. Afraid of being demoted back to the minors, Paul started the season on time.

Paul played in only three games in April, then got his first win on May 3, against the Philadelphia Phillies. In his next appearance, on May 11, he got a complete-game win against the New York Giants and Carl Hubbell.

Before his start against the Giants, while on a train back to St Louis from Pittsburgh, Paul shared a double porterhouse with Dizzy in the dining car. Frisch suspected that Paul was trying too hard to imitate his older brother. Frisch went through the Giants’ lineup, striking pose after pose in the aisle, but never mentioned Dizzy’s name. “I kept telling Paul he had the stuff to beat them. When I paid the check, he said his only words, ‘Thanks, Mr. Frisch.’”11

Paul also had a temper. Once he got “considerably nettled” because the Giants club would not give him the free passes for a Polo Grounds game that he had requested for a fellow who had given him a harmonica.12 Another time he got in a fight with Joe Medwick during a poker game on a train. Out of the hand, Paul took a quick look at Medwick’s hole card. Medwick took offense and slugged Dean, who then jumped on the Cardinal outfielder. “Medwick and me made up,” Paul said later. “We was good friends until the day he died.”13

Dizzy continued to push for a raise for Paul. On June 1, though it was his turn to pitch, Dizzy sat in the stands in Pittsburgh in civilian clothes in protest, proclaiming that neither he nor Paul would pitch again until the team met their demands. Paul dressed in uniform that day but agreed with his brother, saying, “What Dizzy says is right.”14 No raise came, and Dizzy returned to the team the next day with a complete-game win against the Pirates.

Baseball columnist Joe Williams hailed the one-day strike as a true breakthrough for the players, with little guys taking on the great moguls, and called for more of the same. “The hired hands of baseball ought to start a labor department and put the pitching Deans in charge. Dizzy and Nutsey indeed!” Williams wrote.15

By mid-July Paul had fared well. His first 21 games included 13 starts. He won ten and lost four, and had one save. Then a sprained ankle on July 12 in Philadelphia caused him to miss nearly two weeks.

One time Casey Stengel asked Dizzy if he had any more brothers. Diz replied, “We got another brother named Elmer, and Casey, you ought to grab him. He’s down at Houston, burnin’ up the league.” Stengel actually pursued the tip, until he learned that Elmer was a peanut vendor for the Texas League club.16 Dizzy arranged for the Cardinals to hire Elmer at Sportsman’s Park in St Louis, and the headline read “The Dean Brothers — Two Nuts and One Goober.” Embarrassed, Dizzy’s wife, Pat, insisted that Elmer go back to the minor leagues. When he got back to Houston, Elmer went on strike himself and asked for a raise.17

Both Deans lost on the same day in a doubleheader August 12 against the Chicago Cubs. The team had an exhibition game the next day in Detroit against the Tigers. Upset by their double loss, plus the burden of playing on a day off, the Dean boys rebelled. “I ain’t going,” insisted Dizzy. “Me, neither,” added Paul.18

When the Cards returned, on August 14, Paul’s 21st birthday, team owner Sam Breadon fined Dizzy $100 and Paul $50 for missing the game. Dizzy tore up his uniform in disgust and refused to pay the fines. “We’re quitting this club and goin’ to Florida to fish,” he said.19 Breadon suspended them both indefinitely, even though Dizzy had already won 21 games and Paul 12. The boys watched the game on August 15 from the grandstand.

In the midst of this brouhaha, Paul’s nickname, Daffy, first appeared on August 15, in a story in the Brooklyn Eagle, with no byline. He never embraced the term, and asked writers not to use it. Neither his teammates nor family members ever used the term to refer to him.20 Will Rogers even made a direct appeal on Paul’s behalf at a baseball writers dinner for them not to use the term.21 Yet scribes and fans alike seemed attached to the moniker, and the brothers were continually referred to as Dizzy and Daffy Dean. Sometimes his teammates called him Harpo, after the mute member of the Marx Brothers, due to Paul’s very quiet yet sometimes mischievous personality.22

People interviewed on the street were not sympathetic, referring to the brothers as selfish, ungrateful, spoiled brats.23 Paul relented and paid his $50 fine and $70 of lost salary. He returned to the team to earn his 13th win on August 17. Dizzy ended his revolt a few days later, after a hearing before Commissioner Kenesaw Mountain Landis.

On September 21 Dizzy pitched a three-hit shutout in Brooklyn in the first game of a doubleheader. In the second game, Paul pitched a no-hitter against the Dodgers, not allowing a baserunner after a first-inning two-out walk. Dizzy remarked, “Shucks, Paul, you shoulda told me you was gonna pitch a no-hitter, then I woulda pitched one, too!”24 Paul later remembered that after the game, “Me ’n’ Diz went out to get our supper, and he says I did so good, I wouldn’t have to pay for his supper.”25

The Cardinals won 24 of their last 31 games to capture the pennant from the Cubs and the Giants. Dizzy and Paul won 14 of those games, while losing only four. Paul finished his rookie year with 19 wins and 11 losses. Diz won 30, more than fulfilling his promise to win 45 games between them.

Dizzy won the first game of the World Series, in Detroit on October 3, but the Tigers prevailed the next day. Back in St. Louis on October 5, Paul started the third game. Without sharp control — he walked five and gave up eight hits — he held the Tigers to one run, and the Cardinals won, 4-1.

Back in Detroit on October 8, Paul started Game Six, now an elimination game for the Cardinals, behind in the Series 3 games to 2. Schoolboy Rowe started for Detroit, in front of the 45,551 fans, the largest crowd of the Series. Paul’s single in the seventh inning broke a 3-3 tie, scoring Leo Durocher. The Cards went on to win, 4-3, and Paul earned his second victory of the Series. The Cardinals took Game Seven easily, 11-0, behind Dizzy’s shutout pitching, his second win of the series, making St Louis the 1934 world champions. The Dean boys were the stars of the Series, as they notched all four of the Cardinal victories, with Paul not suffering a loss. Two pitchers seldom dominate a World Series, and no two brothers ever have.

Reporters who covered the Cardinals often remarked on their rough style of baseball and their competitiveness in winning the championship. Dan Daniel, in the New York World-Telegram on October 9, described the outcome as the “gas house gang playing the nice boys from the right side of the tracks.”26

After the World Series the Deans started a barnstorming tour of the country, organized by Ray Doan. They teamed with local white semipro players and played most of their games against Satchel Paige and other prominent black teams, such as the Kansas Monarchs and the Pittsburgh Crawfords. The games often drew big crowds, many times the biggest the towns had ever seen, but “wreaked havoc with Jim Crow customs.”27

Every day for two weeks the tour carried the Deans to a different town, with stops in Oklahoma City, Kansas City, Wichita, Des Moines, Chicago, Milwaukee, Philadelphia, Brooklyn, Baltimore, Cleveland, Columbus, and Pittsburgh.

In Des Moines, Paul left a game early, complaining of soreness in his throwing arm. He had slipped while warming up in the outfield, perhaps “the beginning of arm woes that would hasten the end of Paul’s career at the too-young age of 27.”28

The rough travel schedule left no room for a good night’s rest and began to wear on Paul. Though the money began to roll in, he became very worried about his aching arm. He sat out some games, played outfield in others, and threw underhand if he had to pitch. Cardinals owner Breadon gave direct orders for Paul to stop the tour. Paul visited a doctor in Philadelphia, who prescribed rest.

More money came in as the boys moved on to vaudeville, from Broadway’s Roxy Theater to points as far west as Milwaukee. They signed a monthlong contract with the theatrical producers Fanchon and Marco, bringing in $5,000 a week. On stage, Dizzy did the talking, and Paul played the quiet, straight man.

They became movie stars, in Dizzy and Daffy, with Shemp Howard, later of Three Stooges fame. The movie, filmed in a high-school stadium, featured the two brothers as rookie hurlers called up from the “Farmers,” a minor-league team, to lead the Cardinals to the World Series. Howard got in lots of stunts as their half-blind pitching coach, and the film gave fans some actual footage of the Deans from the World Series. Dizzy’s wife, Pat, estimated that after finishing the vaudeville tour, they had earned at least $35,000.29

The brothers also joined Ray Doan, one of the main promoters of their exhibition tour, in his baseball school in Hot Springs, Arkansas. The city built a new field and commissioned it Dean Field.

The tag “Dizzy and Daffy” marketed well, earning the Deans endorsements for such things as table baseball games, sweatshirts, and cigarettes. Twice they won court battles against corporations using their names without permission. One man tried to trademark “Dizzee and Daffee” sweatshirts, and another developed the “Dizzy and Daffy Bar, Dean of Candy Bars.”30

Back home in Arkansas, Paul began dating Dorothy Sandusky, Miss Russellville of 1933. After a two-month courtship, they were married on December 21, 1934, beginning 47 years of married life. Asked what his older brother might think about his short courtship and wedding, Paul replied, “It’s none of his business, anyhow.”31

The 1935 season began with Paul again holding out for more pay, on Dizzy’s initiative. Dizzy wanted $25,000 for himself and $15,000 for Paul;32 he eventually signed for $18,500, still the highest for any National League pitcher. Still seeking as much as $10,000, Paul refused Cardinals offers that reached $8,500, but he finally settled for the $8,500, plus a $500 gift.

In early May, Paul got into a dispute over balls and strikes with umpire Dolly Stark. He threw a fit and stalked off the mound after walking three batters. “Gee whillikins, I wished I had a hun’red thousand dollars,” he said. “I’d walk right up to Stark and punch him square on the nose. Then I’d do the same to [Cy] Rigler. But I ain’t got the hun’red grand.” “Okay, Paul,” said Diz. “We’ll save up our money, get the 100 grand, and then we’ll both punch ’em on the nose.”33

Dizzy and Paul disliked playing exhibition games during the season. On July 5, 1935, the Cardinals headed to Minnesota to play the St. Paul Saints. Fans anxiously awaited the famous pair, but they both sat in the dugout and refused to take a bow. Dizzy had pitched the day before in Chicago, and Paul would start soon in St Louis. The busy schedule had begun to wear them both down.

The Cincinnati Reds installed lights at Crosley field that year, and scheduled seven night games, one against each of the other National League teams. Nearly 30,000 fans piled in to see the Cardinals face the Reds under the lights on July 31, Paul’s turn to pitch. The overflow crowd forced many of the spectators to find places on the playing field, mostly in foul territory. In the bottom of the eighth inning, Reds outfielder Babe Herman struggled his way through the mob to take his turn at the plate. Spectator Kitty Burke, a local nightclub entertainer wearing a pink dress, grabbed the bat from Herman and stepped into the batter’s box. Paul bluffed a few exaggerated windups, then she hit his underhand pitch back to him. He easily tagged her out. Cards manager Frisch protested, to no avail, that the out should count. Kitty appeared for weeks afterward in clubs around Cincinnati, billing herself as “The Only Girl Who Ever Batted in the National League.”34

Paul began to lose his focus on baseball by mid-August. According to Dick Farrington in The Sporting News, he was “not keenly interested in continuing his pitching career.” With much more money than he could have ever imagined, he seemed ready to drop back to his life on the farm. “Paul would like to break away from the spotlight and be himself — an Arkansas, or if you prefer, an Oklahoma lad without the worry of the diamond,” Farrington wrote.35

The Deans held the Cards in the 1935 pennant race almost by themselves. St Louis sat in first place from August 25 through September 13, but the Cubs won 21 games in a row and took the pennant from the Cardinals by four games. Together Paul and Dizzy logged 595 innings. Dizzy won 28 games and Paul won 19 again, repeating for the second year in a row the promise Diz had made in early 1934 that they would total 45 wins.

After the 1935 season, Paul bought a farm in Garland, Texas, just east of Dallas. He took some time out for more barnstorming, even with his arm bothering him again. He dropped out of the tour when his wife became hospitalized in St Louis with a serious illness. He later worked again with Dizzy and other pro ballplayers at Doan’s baseball academy and played some golf.

One time umpire Lee Ballanfant joined Paul on the links at Tennison Park in Dallas. Paul shot a 99, after an 83 just two days before, and blamed his poor play on Ballanfant, saying, “How could I do anything with a ‘tom’ looking over my shoulder on every shot?” He later played another nine holes with Ballanfant, at a dime a hole.36

When contract time came, Paul threatened to stay on his farm all summer if he did not get the $15,000 he wanted. His contract came back with $8,500, a repeat of his pay for the last season, and he and Dizzy began to sit out spring training.

Dizzy got the sportswriter J. Roy Stockton to write a letter for him to Branch Rickey in which he extolled his family’s loyalty to the club but also mentioned the many innings and wins that they had contributed the team. After a meeting with Rickey, Dizzy agreed to $22,800. Paul agreed to take $12,00037 and reported to camp on the last day of spring training. “I weighed 235 pounds and that was about 50 over my regular weight. I had trouble getting into shape,” he said.38 He blamed playing golf in Bradenton, Florida, during the offseason for the extra poundage. “I think that was the thing that hurt my arm. I had no looseness in throwing. I was always tightened up.”39

The 1936 season seemed like a split season, with a good start followed by horrible results. After missing a large part of camp, Paul started slowly with three starts in April, but had a solid May, with three complete-game victories and a 2.91 ERA.

On June 2, with only two days’ rest, Paul pitched a shutout for eight innings against Brooklyn, but allowed four runs (three earned) in the ninth. Two days later he pitched two innings in relief against Brooklyn, gave up three runs, and took the loss. He remembered feeling a little twinge in his shoulder that did not bother him at the time, “but when I went out the next day to get in a pepper game, I couldn’t hardly raise it.” He did not realize that he had torn a piece of cartilage. He tried resting, and even blamed his pain on a sore tooth.40 After X-rays ruled out a dental problem, Dr. Robert F. Hyland, the Cardinals’ physician, diagnosed a pulled tendon and prescribed “easy throwing for a few days.”41 Paul again felt like leaving baseball and returning to his farm.

He never dominated hitters in the big leagues again. After the day he felt pain in his arm, he pitched in only five more games that season, giving up 28 hits in 13⅓ innings, with a 13.50 ERA.

At the end of the 1936 season, Paul had won a total of 43 big-league games. He won only seven more. Although he attempted to come back several times, he posted only mediocre results the rest of his career. After 1936, he appeared in 54 games, with 13 starts, over parts of five seasons, and allowed 210 hits in 179 innings and a 4.32 ERA.

On August 25, 1936, Paul requested voluntary retirement status and retreated to his farm near Dallas to rest, hoping to return strong the next season. The Sporting News saw Paul’s problems in 1936 as “the prime reason why the Cardinals are not in first place by a comfortable margin.”42 Branch Rickey commented that Paul “was a complete loss [this season]. We would have been stronger if he never had played this season.”43 Paul “simply pitched himself into a collapse,” commented writer Kyle Crichton.44

Several factors contributed to Paul’s arm failure: barnstorming for two tours, the lack of immediate and proper care for his ailment, missing most of the spring work in 1936 and reporting several pounds heavier than usual, and the extra heavy work his first two years with the Cardinals, especially pitching without adequate rest between appearances. Yet Dizzy downplayed the seriousness of Paul’s ailment, saying, “There ain’t nothin’ wrong with Paul. It’s all in his head.” Replied Paul, “But my shoulder’s where it’s hurtin’, Diz.”45

Paul sought reinstatement in January 1937, and signed a contract that could potentially equal the previous year’s salary if he could repeat some of his earlier success. He assured Rickey that his arm felt as good as ever. His spring work, however, did not look promising, as he did not show the same zip on his fastball, and he again reported to camp overweight. He reported a “relapse of the arm trouble” and visited Lee Jensen, a Southern Association trainer, when the Cardinals were in Chattanooga, wrapping up their exhibition season. After some quick work with “muscle manipulator” Jensen, Paul returned to his team.46

The Cardinals used Paul in relief against the Cubs on April 24, but he gave up a hit and two walks without retiring a batter. He returned to Dr. Hyland for surgery to remove a piece of torn and ossified cartilage in his right shoulder.47 Several weeks later Hyland told him to go out and throw as hard as he could. Paul replied, “Doc, was I to do that, the arm would open up and everything would fall out.”48 Nevertheless, Paul did try to work out but never got his arm stretched into playing shape. The Cardinals asked waivers on him in midseason, but he did not pitch again that year.

Well rested after an offseason spent on the farm and playing golf in Florida, Paul returned to spring training in 1938, hoping for a new start. Wayne K. Otto of the Chicago Herald and Examiner predicted, “Few arms that were as bad as Daffy’s ever recover their normal strength.”49 The Cardinals re-assigned Paul to Houston, hoping he could regain some strength pitching for the Buffs. In an unusual move, Dean moved to another team in the same league, the Dallas Steers, owned by the Chicago White Sox but closer to his farm. He relied mostly on a side-arm curveball, throwing his true fastball only a few times each game.

The Cardinals recalled the rejuvenated Dean in September for five games, including four starts. He won three games and posted a 2.61 ERA in 31 innings. Paul pleaded with owner Breadon not to send him on trips to the north, thinking the cold weather would further hinder his arm’s recovery. “This sore-arm business has become an obsession with Paul,” commented sportswriter Dick Farrington.50

As spring training started in 1939, Paul continued with the Cardinals but began to distance himself from his older pitching brother. “Dizzy meant all right, but he’s responsible for my arm trouble,” he told Sid Keener of the St. Louis Star-Times. “He made me hold out in the spring of 1936.” Paul said he had a rare confrontation with his brother and told him “to go his way and I’d go my way. I wished him all the luck in the world, but from now on I was attending to my own affairs.”51

By mid-August Paul had appeared in only 16 games for 43 innings and a 6.07 ERA. The Cards sent him to Columbus of the American Association. After the season, the New York Giants claimed Paul in the Rule 5 draft, but he announced in February that he was retiring. He said he preferred not to go through another training season. (Paul’s wife, meanwhile, said he would be out only for the 1940 season.)

Then in March, Paul changed his mind and asked Giants manager Bill Terry to assign him to Dallas of the Texas League. In the end, he played for the Giants and had a fairly respectable season, pitching 99⅓ innings, with four wins and four losses and an ERA of 3.90.

Dean returned to the Giants in 1941 but pitched in only five early-season games, all in relief, with a 3.18 ERA, allowing five hits in 5⅔ innings. On May 14 the Giants sold him to the Sacramento Solons of the Pacific Coast League (property of the Cardinals, with Pepper Martin as manager). Paul never reported to Sacramento, however, claiming he would not play that far away from his home in Texas. Consequently, he found himself suspended from baseball.

In April 1942 Sacramento sent Paul to the Houston Buffs, where he successfully re-established his pitching skills. He won 19 games and lost 8, allowing 182 hits in 219 innings and posting a 2.05 ERA. Impressed, the Washington Senators arranged on October 1 to purchase his contract from the Cardinals.

Paul seriously contemplated skipping his assignment with the Senators in favor of staying with his defense job as a guard in an aircraft company plant near Dallas. The Senators meanwhile traded him to the St. Louis Browns for pitcher Elden Auker. When Auker decided to quit baseball and do defense work, the Browns bought Dean outright from the Senators.

Paul entered the 1943 season with excitement about his prospects to return to form. He had worked during the winter in Arkansas, operating a barrel-stave mill with his father-in-law, sawing and chopping though not a lot of throwing, and felt in prime physical condition. He pitched his final three major league games in May for the Browns, with 3.38 ERA in 13⅓ innings, then decided to return to the barrel-stave factory.

On the Browns’ retired list now, Paul passed an Army physical on February 25, 1944. As he awaited his call-up to military service, the Browns released him to play for Little Rock of the Southern Association. He worked an agreement with the team to play only in home games, to remain close to home and supervise at the stave mill. The Browns recalled him in August, simply to protect him from the baseball draft.

In October 1944 the 31-year-old father of three reported to Camp Chaffee, Arkansas, for induction into the Army. When he finished basic training at Fort Riley, Kansas, he was sent to the Fairfield-Suisun Army Air Base in California as a staff sergeant and managed the Air Transport Command’s baseball nine in a 50-game season.

After his discharge from the Army, Paul began workouts at his Texas farm in December 1945. For a while he had thoughts of pitching in the major leagues, but he did not want to pitch in day games, because “my trouble, they told me, was bursitis — and I can’t pitch effectively under a hot, humid sun.”52 He changed his mind and waived his protection under the GI Bill to return to his major-league job. He requested a transfer back to Little Rock and played briefly in the summer of 1946 for Sherman, Texas, in the Class C East Texas League.

Looking for a “name player,” the Ottawa Nationals of the Class C Border League grabbed Paul as their manager for the 1947 season. He even pitched a few innings. After winning the league championship, Paul abandoned the team amid local controversy. Editorials in the local sports pages protested that professional baseball did not fit in their stadium. Paul took offense. “You-all can’t run a ballclub with opposition like that on the editorial page,” he said as he vowed not to return the next year.53

The next several years, Paul spent most of his time in Little Rock. He operated the Purple Cow restaurant, contributed to Little Rock Junior College, and re-created major-league games from wire reports on a local radio station. He also traveled some as a scout for the Browns across Texas, Oklahoma, Louisiana, and Arkansas. He re-entered the baseball world in 1949 when he purchased the Clovis, New Mexico, team in the Class C West Texas-New Mexico League. In 1950 he served as president and manager of the team. In 1951 he shifted to operating the Lubbock Hubbers in the same league. The team fared well, with higher attendance than in any of the previous four years. Dizzy joined Paul as a silent partner in the Lubbock venture, each of them investing money they would make from Hollywood.

Controversy swirled around Paul when Twentieth Century-Fox decided to make a movie about Dizzy’s life. He first balked at the $15,000 offered by the producers for the use of his name. He wanted $25,000. He also insisted on approving the script. He feared that the movie would include “a lot of love stuff” instead of the true Dean family story54 — which he claimed would surely bring in much bigger crowds than any fictionalized accounts. “Tell a true story based on our lives, and if the public doesn’t come out in larger numbers the second night than the first, I’ll do it for nothing,” he said.55

The younger Dean perceived the elder Dizzy and his wife, Pat, attempting to twist his arm to get him to follow their plans. He was especially unhappy about a Saturday Evening Post article, “Dizzy Dean: He’s Not So Dumb,” by a Dallas News sportswriter, Frank X. Tolbert. Paul felt Tolbert used Dizzy’s words to denigrate their modest upbringing and their limited educational experiences. For example, Tolbert had written, “J.H. Dean [Dizzy] was easily the most backward and ornery scholar in the one-room schoolhouse at Chickalah, Arkansas,” and that he was “figured least likely to succeed.”56

Tolbert retorted that he had spent a full morning going over the article with Dizzy before it was published.57 Paul preferred to stay in the background, despite Dizzy’s talkative tendencies. “My wife Dorothy and I have three children, and we want them to lead a quiet, normal life,” he said. “If Diz doesn’t mind zany stories about himself, that’s okay by me. But because of my children, I wish he would leave me and all the rest of the Deans out of his stories.”58

Eventually Paul made peace with Dizzy and Pat and signed the movie contract. The Pride of St. Louis — the Story of Dizzy Dean premiered on April 11, 1952, with Dan Dailey as Dizzy and Joanne Dru as his wife, Pat. Richard Crenna moved up from radio to take the role of Paul.

In February 1953 Paul moved his family — now with four children — to El Paso to become general manager of the El Paso Texans of the Arizona-Texas League. He planned to step on the field as manager, too, if needed, and he intended to promote attendance by having Dizzy make personal appearances, as he had for the Lubbock team. He left the El Paso job in April 1953, but returned to baseball for the 1954 season as president, general and business manager, and field manager with Hot Springs of the Class C Cotton States League.

In 1955 Paul’s son, Paul Jr., impressive as a high-school pitcher in El Paso and Little Rodk, signed to play baseball for Southern Methodist University in Dallas. He registered for premedical studies, heading for a degree in dentistry.59 In his freshman season, however, he lacked control on the mound, as well as his share of self-confidence, surrendering a large number of home runs. Some felt he was trying too hard, striving to match the reputation of his famous pitching family.60 In 1957 the 18-year-old left baseball at SMU and signed with the Milwaukee Braves, who assigned him to Syracuse in the American Association. He also played with Lawton of the Sooner State League that season. He developed arm trouble of his own the next year, and left professional baseball in midseason of 1959.

Paul spent several years in various business ventures, including managing several service stations in the Dallas area and running Dizzy’s carpet business in Phoenix. He accepted a new challenge in April 1966 as baseball coach and athletic director at the new University of Plano, just north of Dallas. Now a grandfather of six, Paul began to set up programs for football and track and field, as well as for baseball. “I don’t know much about coaching football, but I know conditioning and fundamentals are important in any sport,” he said. Remembering his recent experience with minor-league teams, he remarked, “I was president, groundskeeper, clubhouse boy, and manager. I did it all. Yeah, I know I can coach baseball.”

In his later years Paul used his playing skills in several old-timer’s games, including reunions of the old Buffs teams in Houston, in which he and Dizzy were hailed as “the two most popular players in the entire Houston baseball history.”61 In 1973, at nearly 60 years old, he matched up once again with Satchel Paige, 67 years old himself, in an old-timer’s exhibition.62

Dizzy had heart problems in the summer of 1974, beginning with a heart attack on July 11. He had another severe one four days later. Paul joined his sister-in-law Pat at Dizzy’s side in Reno, Nevada, where his brother on died July 17.

On March 17, 1981, Paul died of a heart attack in Springdale, Arkansas. He is buried in Oakland Cemetery in Clarksville, Arkansas.

In their two healthy years together, the Dean brothers combined for a 96-42 won-loss record, with an ERA slightly over 3.00. They had similar pitching motions, and looked and talked alike. They enjoyed many of the same things: Jean Harlow and Mae West movies, hillbilly music, Lucky Strike cigarettes, FDR, golf in Florida, quail hunting, peanuts, cold milk, and beating the New York Giants. They lived in the same hotel on the same floor, and used the same barber, shoeshine boy, grocer, and mechanic. Each also believed his arm would last forever.63

As J. Roy Stockton told it, “Dizzy talked. Paul listened. Dizzy wisecracked. Paul laughed. Dizzy was a great comedian. Paul was his best audience. Each was the other’s hero.”64

Yet they had very different, if not opposite, personalities. After his first year with the Cardinals, reporters recognized that, as The Sporting News put it, Paul “does not have the color or the swaggering egotism of his older brother, nor the latter’s ready tongue or unconscious braggadocio that the public likes. Reticent, unassuming, and retiring, Paul is not the kind that the fan can slap on the back, or bandy wisecracks with, but Dizzy glories in all that. Paul never will fit into the showmanship role that Dizzy occupies, thought he younger Dean gives promise of equaling and even surpassing his older brother as a pitcher.65

Paul saw the world through the eyes of his simple country upbringing. After the 1934 World Series victory, Dizzy bought an airplane to celebrate. Paul bought a farm. He once remarked, when he heard what Bill Walker, the fashion plate of the Cardinals, had paid for a suit, that that was more than he had ever spent for all the clothes he had ever owned.66

He said it best in his own words: “Gee, we’re just a couple a natural pitchers and ordinary fellas, but God gave us perfect pitchin’ builds — long and loose like houn’ dogs. We never ate no special vittles or nothin’ like that to put speed in our soupbones, just lucky fellas to be born great pitchers.”67

This biography is included in the book “The 1934 St. Louis Cardinals: The World Champion Gas House Gang” (SABR, 2014), edited by Charles F. Faber. For more information or to purchase the book in e-book or paperback form, click here.

Notes

1 Sources vary as to Paul’s actual birth year. His school enumeration in Spaulding, Oklahoma, said 1911. His Social Security records as well as baseball-reference.com list 1912. His marriage-license records, his Army enlistment records, his grave index, and various biographers of Dizzy Dean all say 1913.

2 Robert Gregory, Diz — Dizzy Dean and Baseball During the Great Depression (New York: Viking, 1992), 25. (Hereafter cited as Diz).

3 Vince Staten, Ol’ Diz — A Biography of Dizzy Dean (New York: Harper Collins, 1992), 13. (Hereafter cited as Ol’ Diz).

4 Ol’ Diz, 24.

5 Ol’ Diz, 105.

6 “Introducing Paul Dean, Dizzy’s Kid Brother,” The Sporting News, March 26, 1931, 5.

7 “Paul Dean Just Another ‘Dizzy,’ ” Massillon (Ohio) Evening Independent, October 26, 1933, 8.

8 “Milestones.” Time, March 30, 1981, 86.

9 Dizzy claimed the prediction, but some sources credit it to the Cardinals’ public-relations man, Gene Karst, (See Ol’ Diz, 103).

10 Diz, 125.

11 Diz, 135.

12 Dick Farrington, “Fanning with Farrington,” The Sporting News, December 10, 1936, 4.

13 John Heidenry, The Gashouse Gang, (New York: Public Affairs, 2007), 118. (Hereafter cited as The Gashouse Gang).

14 The Gashouse Gang, 134.

15 Diz, 152.

16 J. Roy Stockton, The Gashouse Gang and a Couple of Other Guys. (New York: A.S. Barnes, 1945), 31.

17 Diz, 167.

18 Milton Shapiro, The Dizzy Dean Story (New York: Julian Messner. 1963), 92.

19 The Gashouse Gang, 165.

20 Diz, 171.

21 J. Taylor Spink, “Three and One — Looking Them Over,” THE SPORTING NEWS. October 3, 1935, p. 4.

22 Timothy M. Gay, Satch, Dizzy, and Rapid Robert (New York: Simon and Schuster, 2010), 77.(Hereafter cited as Gay).

23 Diz, 171.

24 Shapiro, The Dizzy Dean Story, 99.

25 Diz, 195.

26 Diz, 237. (Joe Williams of the World Telegram actually introduced the idea five days earlier when he wrote of the Cardinals, “They looked like a bunch of boys from the gas house district who had crossed the railroad tracks for a game of ball with the nice kids,” Diz, 213).

27 Gay, 81.

28 Gay, 85..

29 “Deans Still Dazzle ‘Em,” The Sporting News, October 18, 1034, 1.

30 Ol’ Diz, 158-159.

31 Heidenry, The Gashouse Gang, 283.

32 Shapiro, The Dizzy Dean Story,122.

33 “A Hundred Grand Orgy.” The Sporting News, May 16, 1935, 5.

34 John McDonald, “Night in Cincy When McDonald Wished for a Farm,” The Sporting News. December 30, 1943, 8. “Crosley Field — First Lighted Big League Park — Always Packed Opening Day.” The Sporting News. February 26, 1947, 15; Dick Kaegel, “Inside Corner — Swinging Blonde ‘Pinch-Hit’ for Babe,” The Sporting News, November 26, 1966, 4.

35 Dick Farrington, The Sporting News. August 29, 1935, 1.

36 “Daffy Dean Makes His Debut as Tournament Golfer Under Handicap — Against an Umpire,” Corsicana (Texas) Daily Sun, February 11, 1936, 8.

37 Reports of Paul’s 1936 salary vary from $10,000 to $12,000.

38 “Obituary,” The Sporting News. April 4, 1981, 54.

39 Grantland Rice, “The Sportlight,” Syracuse Herald,. March 27, 1939, 14.

40 Diz, 288.

41 “Pitching Puts Two Strikes on Cards,” The Sporting News. July 16, 1936, 1.

42 “Vulnerable Cards Spoil Pennant Hand,” The Sporting News. September 3, 1936, 3.

43 Edgar G. Brands, “Cards Turn Down $100,000 Bid for Minor Star, Rickey Reveals,” The Sporting News, September 17, 1936, 5.

44 Kyle Crichton, “All Pitched Out,” Collier’s, April 1, 1939, 20.

45 Diz, 289.

46 “Browns in the Pink as Barrier Goes Up,” The Sporting News. April 22, 1937, 3.

47 Red Byrd, “Hit-and-Miss Pace Jars Hornsbymen,” The Sporting News. May 13, 1937, 2.

48 J.G. Taylor Spink, “Three and One,” The Sporting News. June 24, 1937, 4.

49 “Scribbled by Scribes,” The Sporting News, March 31, 1938, 4.

50 Dick Farrington, “Cards Look Better to Owner Than Fans,” The Sporting News, April 13, 1939, 6.

51 “Scribbled by Scribes,” The Sporting News, March 23, 1939, 4.

52 “Paul Dean Says He Can Pitch Night Games in Majors,” San Jose News, July 21, 1945, 35.

53 Austin F. Cross, “Dean’s Run-Out During Playoffs at Ottawa Laid to Editorial Rap,” The Sporting News, October 22, 1947, 25.

54 Choc Hutcheson, “Paul Says He’ll Tell True Story of ‘Me and Diz,’” The Sporting News. July 18, 1951, 23.

55 “Refused Peek at Script, Paul Snubs Dizzy’s Film,” The Sporting News, January 24, 1951, 16.

56 Frank X. Tolbert, “Dizzy Dean: He’s Not So Dumb!” “Saturday Evening Post,” July 14, 1951, 25.

57 Bill Rives, “ ‘Diz’ Boswell Suggest Commission to Sift Dean History,” The Sporting News, August 8, 1951, 16.

58 Choc Hutcheson, “He’s Writing Book Called ‘Me an’ Diz,’” The Sporting News, August 1, 1951, 6.

59 Charles Burton, “Paul Dean Jr to Pitch for Mustangs Next Season,” Dallas Morning News, June 29, 1955, 15.

60 Charles Burton, “Young Paul Dean Trying Too Hard,” Dallas Morning News, April 20, 1956, 19.

61 John F. Lyons, “9,828 See Former Buffs, Hallahan and Diz, Pitch,” The Sporting News. July 16, 1952, 34.

62 Gay, 283.

63 Diz, 4-5.

64 Stockton, 29.

65 “The Dean Brothers,” The Sporting News, October 18, 1934, 4.

66 J.G. Taylor Spink, The Sporting News, June 11, 1936, 4.

67 Diz, 202.

Full Name

Paul Dee Dean

Born

August 14, 1912 at Lucas, AR (USA)

Died

March 17, 1981 at Springdale, AR (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.