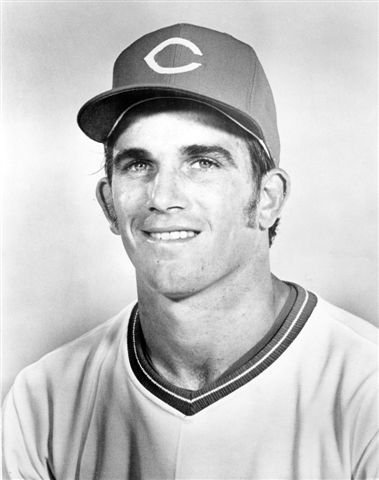

Bill Plummer

Role players have long existed in baseball. At least since 1910, when roster numbers were set at 25 active players and 40 reserved players, teams have kept bench players who filled certain key situational roles. And this tendency has only increased as the game has evolved over time and player specializations have proliferated. During the 1970s, no one typified the career “role player” any more than Bill Plummer.

Role players have long existed in baseball. At least since 1910, when roster numbers were set at 25 active players and 40 reserved players, teams have kept bench players who filled certain key situational roles. And this tendency has only increased as the game has evolved over time and player specializations have proliferated. During the 1970s, no one typified the career “role player” any more than Bill Plummer.

Born on March 21, 1947 in Oakland, California, William Francis Plummer moved with his family at the age of 8 to horse country in Anderson, California, in the northern part of the state. His father, William Lawrence Plummer, was a former minor-league pitcher who, after a 25-year career with the Oakland police, retired to ranch and teach his son the game. “He was a gruff man,” said Plummer in later years, “but big-hearted. A good man.” The elder Plummer kept Bill from becoming a little-league pitcher, worried that it would ruin his son’s arm as it had his. “I used to throw a little relief, but he wouldn’t let me throw a curveball. He taught me a forkball.”1 Plummer played basketball as well as baseball, and while at Shasta College in Redding, California, he was named to the All-Conference hoops team before deciding to make a career of baseball.

Signed in 1965 by the St. Louis Cardinals as an 18-year-old, 6-foot-1, 190-pound catcher out of college, Plummer first played for the Cardinals’ Rookie League team in Sarasota that summer. In 42 games he played well enough—batting .265, providing solid defense behind the plate, and playing in the Florida Rookie League all-star game—to be moved up to the Cardinals’ Class A team in Cedar Rapids, Iowa, right before the end of the season. In 1966 Plummer played in low-A for the Eugene Emeralds (Northwest League), struggling at the plate (.144 batting average and just one home run in 46 games) and, uncharacteristically, behind it (seven passed balls). In 1967 Plummer’s season went slightly more smoothly. With Modesto, another Single-A team, he raised his batting average to .234 and played better defense—but not so smoothly that the Cardinals protected from the Rule 5 draft by placing him on their 40-man roster. In late-November 1967, Plummer was drafted by the Chicago Cubs.

Plummer may have been simultaneously well-served and paid a grave disservice by the rules of the draft. Being chosen by the Cubs gave him a higher profile than he might otherwise have earned over the next several seasons. At the same time, this might also have significantly hindered Plummer’s development as a player. Because the Cubs had to keep him on the major-league roster for the entire season, lest they lose rights to him, Plummer almost stayed on the bench for the entire season in 1968, appearing in just two games and recording no hits in two at-bats. (Starting catcher Randy Hundley appeared in a record 160 games that year.) Plummer figured enough in the Cubs’ future plans that he was sent after the season to the Arizona Instructional League, where he played well against many of the league’s future star players.

Plummer was listed on the Cubs’ 40-man roster, but on January 9, 1969, the team announced that the young catcher had been included in a trade with the Cincinnati Reds that brought reliever Ted Abernathy to the Cubs for Plummer, minor league pitcher Ken Myette, and outfielder/first baseman Clarence Jones. The Reds assigned Plummer to Triple-A Indianapolis, and it was here that he began to blossom as a player. In 1969 he batted .248 with seven home runs in 104 games. More importantly, his defensive skills improved. Early in his minor-league career, Plummer had been rated as a “good receiver who can hit with power but with a lot to learn.”2 After three seasons at Indianapolis, the report had upgraded somewhat: “Ready for majors now if somebody gives him chance. Solid receiver with good arm, shows increasing power at plate.”3 In 1971 Plummer completed his best year as a ballplayer—.266 batting average, 17 home runs, and co-team MVP at Indianapolis—and was increasingly viewed as major-league ready.

The Reds, faced with a play-him-or-trade-him situation, chose to trade their longtime backup to Johnny Bench, 31-year old Pat Corrales, in favor of the younger player. Plummer joined the Reds 25-man roster to stay in 1972. From the start his role in Cincinnati was clear, if unrewarding: He was there to back up Bench, who was one of the team’s franchise players. While Plummer would play occasional games at first and third base, he otherwise filled his role uncomplainingly for seven seasons. Here’s how Sports Illustrated described the typical work day for Plummer toward the end of his stint with the team, in July, 1977: “Bill Plummer of the Cincinnati Reds is diligent and conscientious about his work. He gets to the park early, takes batting and infield practice, runs in the outfield, sings the Star-Spangled Banner, then sits down and spends the rest of the game trying to steal signs. Bill Plummer is the replacement for Johnny Bench, on the bench. … He knows this is all there is. ‘I’m almost a player without a function,’ he sighs.”4

Everyone, including Plummer himself, knew his was a thankless job. In 1974 a reporter seemed surprised that Reds pitcher Fred Norman preferred having the backup catcher behind the plate when he was pitching. Plummer, who overheard the exchange, told the reporter simply, “He likes my ugly face to throw at.”5 Another time, on a cold night in Pittsburgh in 1976, Plummer reportedly helped some of the other bored bullpen occupants build a fire. “We broke up all the wood we could find,” he recalled. “Ripped it off from under the stands, anywhere.”6 The fire nearly caused a major catastrophe when it smoked fans out of the stands near the bullpen—but at least it was an event to break up the endless monotony of the role player.

Aside from the Reds’ two World Series titles in 1975 and 1976, and one other World Series 1972 (during which he failed to make a single appearance), Plummer’s career between 1972 and 1977 had few highlights. In those six seasons, Plummer came to the plate just 871 times; his batting average broke .200 only twice. Plummer holds the dubious distinction of recording the lowest batting average among all National Leaguers in the 1970s: a paltry .189.7 However, up until the Reds let their 31-year old backup catcher become a free agent rather than re-sign him just before the 1978 season, Plummer’s role on the Reds was rarely questioned. “Around the National League,” wrote Barry McDermott in Sports Illustrated, “Plummer is regarded with an unusual degree of respect.”

It was often suggested that the cause of Plummer’s ineffectiveness at bat was simply how rarely he got to play. Plummer’s teammate Pete Rose wondered to McDermott what Plummer would be capable of if given the chance to play two months straight. “He’s a physical fitness nut, and if hard work means anything, he would do all right.”8 Rose may have had a point. Meanwhile, despite Plummer’s weak lifetime batting record, in one three-week stretch from mid-August to early September 1972 when Bench was playing elsewhere in the field due to a broken finger, Plummer stepped in and hit .254 (17 for 67). His highest seasonal batting average, .248, came in 1976, another season in which Bench struggled with injuries. While Bench was out of the lineup during the first two months of the season, Plummer hit .290. Plummer’s single biggest day at the plate came in St. Louis, on June 6 of that season, when he drove in seven runs with a single, triple, and homer.

Plummer was viewed by opponents as tough and powerfully built, a threat if not in actuality then at least in idea. He was also comparable to the Gold Glove-winning Bench behind the plate. Among teammates, Plummer was a guy you’d want to have on your side. “When former teammate Clay Carroll got into a little disagreement in a San Diego bar,” McDermott wrote. “Plummer rescued him with a right cross that floored one rambunctious soul as well as two or three others packed tight behind him.” Sparky Anderson, who coached Plummer in the minors before becoming his skipper in Cincinnati, vouched for his backup catcher’s character: “He’s a man. He doesn’t like what he does. Nobody would like being a caddie. But he handles it.”9 Even many years later, his better known, better paid teammates had nothing but praise for the man they called Plum. “He played hard, with pride,” Ken Griffey Sr. said in 1992. “His playing record was affected greatly by playing seven or eight years behind Johnny Bench. He could have been a starter for anyone else. But he never complained.”10

Plummer only shrugged at such sentiments, saying that while he used to “pray for 300-400 at bats” to show what he could do, “complaining doesn’t change anything.” Though he did regret that he was often embarrassed when he stood at the plate, “because you feel like your talent has rotted. It’s like you haven’t played tennis for two months and you try to play and stumble all around. This game’s the same way, except you’ve got 50,000 people watching you and a guy gets you out although you feel like you’re better than he is.”11

After his release from the Reds, Plummer’s playing career wound down quickly. At age 31, he signed a one-year contract with the Seattle Mariners for their second season as an American League expansion team in 1978. “It was a milk-and-cookie crew compared to the world-champion mentality I was used to,” Plummer said of that team. “Nothing against the kids they had here, but they didn’t play like they were worried about losing their jobs, and that’s what the Reds demanded. Remember, what you expect from people is what you’re going to get.”12 That season Plummer bounced between the minors and big leagues, playing backup to Bob Stinson and batting .215 on a team that lost 104 games. In 1979 Plummer tested free agency and, after getting a nibble from Montreal, settled back with the Mariners with another one-year contract. After spring training he was sent to the Mariners’ Triple-A team in Spokane, where he spent the whole season as a player-coach for manager Rene Lachemann. On October 4, 1979, the Mariners released Plummer, and shortly after, Plummer announced his retirement as a player, adding that he, ever the role player, would welcome a chance to manage in the minor leagues. He didn’t have to wait long.

By the time of his retirement, now three years removed from the swagger of the Big Red Machine, Plummer’s character had somewhat changed from his heyday as a hard-living, hard-fighting teammate. Through the late 1970s Plummer had increasingly turned toward Christianity. “I realized I needed to change,” he said some years later of his years with the Reds. “I don’t think it was wildness. I think it was being young. You take things to extremes. I was a little too cocky, too macho. I got myself into situations where there were fights, yes, mostly in bars. I should have been scared, but I was busy being indestructible.”13 This change may also have been inspired by the example of his father, who had taught his son about life, and about the game. Bill Sr. died in 1979, never having had a chance to see his son manage.

In 1980 Plummer was assigned to manage the Mariners’ high-A team in San Jose (California League), and in 1981 he managed the Wausau (Wisconsin) Timbers to a title in the Midwest League. By then, partway through the 1981 season, Lachemann had been called up to manage the struggling big-league club. In 1982 Plummer went to work for his old manager as the Mariners’ bullpen coach. The role was a good opportunity for Plummer to learn, but also to show what he could do—such as lowering the team’s ERA from a league-worst 4.23 in 1981 to a fourth-best 3.88 in 1982. “I learned a lot from Lach and from Dave Duncan about handling pitchers,” Plummer said later. “Of course, I developed my own ideas, too, from years as a catcher. I always took pitchers’ success or failure personally. After all, I was the one who called the pitches.”14 The position was also a curse, as Seattle managers in those years rarely lasted longer than a season or two. Lachemann was fired less than halfway through 1983, and Plummer found himself managing in the minors again. In 1984 and 1985 he was the skipper of the Mariners’ Double-A team, the Chattanooga Lookouts, and in 1986 and 1987 he took over the helm of the Triple-A Calgary Cannons.

If Plummer had been, for the bulk of his baseball career, stuck in the shadows as a role player, 1987 brought him his first opportunity to take several steps toward the floodlights. That year Plummer took Calgary, after its 1986 record of 66-77 and last-place finish in the Northern division of the Pacific Coast League, to an 84-57 record and first place. (Calgary would lose in the league championship playoffs, three games to one, to the Albuquerque Dukes.) In 1988, buoyed by this success, Plummer returned to coach with the Mariners, splitting time for the next few years as the team’s bullpen and third-base coach. In 1991 Plummer was the third-base coach under manager Jim Lefebvre for the Mariners’ first winning team (in its 15th year of existence). The franchise was on a high, but Lefebvre was not popular with the players, who complained that they were never sure where they stood with him. The Mariners’ front office, feeling that the team could do still better, fired Lefebvre at season’s end and after some deliberation chose Plummer in December 1991 as the tenth manager in the franchise’s short history. The new manager immediately sought to distance himself from the previous manager and give the Mariners a fresh start. “We want to look ahead,” Plummer said. “The Mariners have spent too much time looking back.”15

At the time it appeared Plummer was poised for managerial success. As one of several Reds players managed by Sparky Anderson who went on to become major-league managers (along with Pete Rose, Tony Perez, Pat Corrales, Ray Knight, Hal McRae, and John Vukovich), Plummer had a distinguished pedigree.16 The Mariners also had a stable of young talent—such as third baseman/designated hitter Edgar Martinez, pitcher Randy Johnson, young centerfielder Ken Griffey Jr., and second baseman Bret Boone. And the plain-shooting, straightforward, 45-year-old Plummer seemed the perfect choice to keep the team on a winning track.

But success was elusive from the get-go for the new manager, as the Mariners suffered through a series of early losing streaks and fell into a 15-25 hole by May 20. One big drag on the team was its main offseason acquisition, left fielder Kevin Mitchell, for whom the Mariners had traded three relief pitchers to the San Francisco Giants and who was struggling with injuries while the team’s bullpen was performing poorly. On May 26, Plummer got into a public feud with his star pitcher, Johnson, over the pitcher’s decision to pull himself out of a game. By early August the atmosphere around the team seemed desperate. “I am doing everything I can to help the ballclub win,” Plummer told a beat reporter on August 3. “I haven’t had very good results, but on the other hand, a manager is only as good as his players. If players aren’t doing as well as they should be, then (management) has to make decisions on who needs to go. If that happens to be me, I have to accept it.”17 A 14-game losing streak in September not only broke the team’s back, but likely sealed Plummer’s fate. On October 13, 1992, after the team finished with the American League’s worst record, 64-98 and 32 games out of first place in the AL West, Plummer was fired. It was just a few days more than a year after he was hired. Plummer’s only comment was typically brusque: “It goes with the territory.”18

After a year or two off, Plummer returned to managing in the minor leagues in 1995. He continued to do so, in stints of one or two years, for various teams at various levels, through 2008, when he wrapped up a season managing the Triple-A Tucson Sidewinders in the Arizona Diamondbacks’ system. While he had some success—winning one Double-A league championship and helping turn around the Diamondbacks’ farm system—Plummer was never again considered for a major-league manager position.

A member of the Shasta County (California) Sports Hall of Fame, Plummer in 2012 was a resident, with his wife, Shelly, of Redding, a town of about 90,000 that is 12 miles from where he grew up in Anderson. He has three grown children, Billy, Gina, and Trish, from a previous marriage, and worked as the Diamondbacks’ minor-league catching coordinator.

Last revised: May 1, 2012

This biography is included in the book “The Great Eight: The 1975 Cincinnati Reds” (University of Nebraska Press, 2014), edited by Mark Armour. For more information, or to purchase the book from University of Nebraska Press, click here.

Notes

1 Bob Finnigan, “Plum Truthful—Mariner Manager Bill Plummer Is Direct, Straightforward,” Seattle Times, April 2, 1992.

2 Scouting Report on Cubs system, Baseball Digest, March 1968, 80.

3 Scouting Report on Reds system, Baseball Digest, March 1972, 62.

4 Barry McDermott, “Few Things Come To Him Who Waits: The Reds’ Bill Plummer plays behind the finest catcher in baseball—at times,” Sports Illustrated, July 18, 1977.

5 Hal McCoy, Baseball Digest, September 1974, 43.

6 Bob Hertzel, “The Bullpen Where Characters and Oddball Capers Abound,” Baseball Digest, July 1976, 81.

7 Bill James, The New Bill James Historical Baseball Abstract (New York: Free Press, 2001).

8 Barry McDermott, “Few Things Come To Him Who Waits.”

9 Barry McDermott, “Few Things Come To Him Who Waits.”

10 Bob Finnigan, “Plum Truthful.”

11 Barry McDermott, “Few Things Come To Him Who Waits.”

12 Bob Finnigan, “Plum Truthful.”

13 Bob Finnigan, “Plum Truthful.”

14 Bob Finnigan, “Plum Truthful.”

15 Bob Finnigan, “Plum Truthful.”

16 Baseball Digest, June 2000, 48.

17 Jim Street, “Seattle Mariners,” Sporting News, August 3, 2012.

18 Mel Antonen, “Seattle fires Plummer after last-place finish,” USA Today, October 14, 1992.

Full Name

William Francis Plummer

Born

March 21, 1947 at Oakland, CA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.