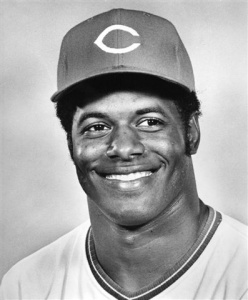

Ken Griffey Sr.

Baseball lore is rich with stories of fathers and sons playing catch in the back yard, of fathers and sons bonding at a baseball park. Ken Griffey’s father never played catch with him, never bonded with him at a baseball park, or anywhere else for that matter. Nevertheless, the youngster grew up to be a key member of Cincinnati’s Big Red Machine and the father of a future member of the National Baseball Hall of Fame.

Baseball lore is rich with stories of fathers and sons playing catch in the back yard, of fathers and sons bonding at a baseball park. Ken Griffey’s father never played catch with him, never bonded with him at a baseball park, or anywhere else for that matter. Nevertheless, the youngster grew up to be a key member of Cincinnati’s Big Red Machine and the father of a future member of the National Baseball Hall of Fame.

George Kenneth Griffey was born on April 10, 1950, in Donora, Pennsylvania, one of five children of Ruth and Joseph “Buddy” Griffey. In his youth Buddy was an outstanding athlete, a left-handed third baseman who played on an all-star team with Stan Musial. A halfback, he won a football scholarship to Kentucky State University, met Ruth, then returned to Donora. Located on the Monongahela River in Washington County, about 20 miles south of Pittsburgh, Donora is the birthplace of three famous athletes – Musial, Griffey, and Ken Griffey, Jr. Environmentalists recognize it as the site of one of the worst air-pollution disasters in American history. In late October1948 a temperature inversion combined with toxic emissions from United States Steel’s smelting plants to create a death-dealing smog. Twenty residents died; thousands were sickened by the calamity. Buddy Griffey was an employee of American Steel and Wire, a subsidiary of US Steel, but his family escaped the ravages of the smog. However, the company closed the plant in 1952 and transferred Buddy to Cleveland. When Ruth refused to join him in Ohio, the couple divorced. Ruth and the children lived on welfare for 15 years.

In high school Griffey became a star in four sports—baseball, basketball, football, and track. In baseball he was a hard-hitting, base-stealing, fine-fielding center fielder. In basketball he was outstanding, once scoring 40 points and collecting 27 rebounds in a game against Charleroi Area High School. It was in football, though, that he received his greatest acclaim. He played alternately at end and halfback and specialized in long runs after catching passes thrown by the quarterback, his younger brother Fred. The two set many passing records for the Donora High School Dragons, who had two consecutive undefeated seasons. Although the baseball and track seasons overlapped, Griffey was able to compete in both sports. He participated in the 220-yard dash, the low hurdles, and the high jump. In May 1969 he set a Washington County record in the high jump at 6 feet ¾ inch. He was named the Donora community’s “Athlete of the Year” in 1969.

After graduating from Donora High School that spring, Griffey briefly joined an American Legion team in nearby Charleroi. In the June 1969 amateur baseball draft, Griffey was selected by the Cincinnati Reds in the 29th round. Of the prospects drafted by the Reds that year, two—Don Gullett and Rawly Eastwick—would eventually join Griffey on the Reds. According to the writer Joe Posnanski, Griffey was drafted solely because of his speed. Scout Elmer Gray had taken a stopwatch to one of the Donora High School games and was amazed at how quickly Griffey could get down the first-base line. On Gray’s recommendation, the Reds drafted Griffey. They would need speed when they moved into the new Riverfront Stadium with its artificial turf. Posnanski wrote that the Reds gave him a red jacket and five pairs of socks in lieu of a signing bonus.1 Although he had offers of college scholarships to play football, Grifffey signed with the Reds. He needed the $500 a month they offered him.

Griffey was sent to Bradenton, Florida, to play for Reds of the Gulf Coast Rookie League. The 19-year-old outfielder appeared in 49 games in his first professional season and hit a respectable .281. In 1970 he was promoted to the low Single-A Northern League’s Sioux Falls Packers, and the next year to the Tampa Tarpons in the Florida State League. He caught fire with the Tarpons, hitting .342 and stealing 25 bases in 88 games. This productivity earned him a late-season promotion and a full year at Trois-Rivieres (Quebec) of the Double-A Eastern League where in 1972 he hit .318 with 14 home runs and stole 31 bases. Clearly he was on his way.

In 1973 for Indianapolis of the Triple-A American Association, Griffey hit .327 and earned a promotion to the Reds when outfielder Bobby Tolan went on the disabled list. The 23-year-old Griffey made his big-league debut in Cincinnati on August 25 against the St. Louis Cardinals. His first major-league hit came in the third inning when he doubled to left off Tom Murphy. He hit well the rest of the regular season, posting a .384 average in 25 games, though he was just 1-for-7 in the NLCS loss to the New York Mets.

Griffey split the 1974 season between Indianapolis and Cincinnati, hitting .251 in the big leagues. He spent 1975 with the Reds as the full-time right fielder. According to Joe Morgan the addition of Griffey as a full-time member of the Reds played a major role in the club’s improvement during the 1975 season. “He was the best fastball hitter I had seen,” Morgan wrote. “It did not matter where you pitched him, in, out, up, or down, he was always able to handle heat. He had speed, he could throw, he was smart in the outfield and never missed a cutoff man.”2 The installation of Griffey enabled the Reds to move Cesar Geronimo full-time to center field, George Foster to left field, and Pete Rose to third base. These switches strengthened the Reds tremendously. Griffey hit .305 with an on-base percentage (OBP) of .391, and scored 95 runs. However, despite his speed, he stole only 16 bases that season. There was a reason: At the start of the season Griffey had batted sixth, seventh, or even eighth. When manager Sparky Anderson moved him up to hitting mainly second in the lineup, he told Griffey: “Kenny, I’m moving you up to the number two spot in the lineup. That’s because I think you’re a great hitter. But there’s one thing you need to know. From now on I don’t want you stealing any bases. You got Joe Morgan hitting after you, and he’s the best damn player in the game of baseball, and he doesn’t like when people steal bases when he’s batting. It distracts him. So you don’t steal.”3

Although he resented having his greatest asset—his speed—taken away from him, Griffey did not complain. On the 1975 Reds Anderson and the four stars (Morgan, Tony Perez, Rose, and Johnny Bench) ran the team. The other players were expected to do as they were told. Much later Griffey said, “I could have been a whole hell of a lot different player. I could have been a very selfish player. I could have been like Joe Morgan. … Joe knew he couldn’t run with me. I could have stolen just as many bases as he did. I could have stolen more bases. Back in 1973, I was the best there was at stealing bases. … Sparky told me I couldn’t steal bases because it bothered Joe’s hitting. … I sacrificed for the team. I always sacrificed for the team.”4

The Reds won 108 games in 1975, finishing 20 games ahead of Los Angeles in the NL West. When the Reds faced Pittsburgh in the NLCS, Anderson shuffled his lineup. Morgan wanted to bat second, and Anderson obliged by dropping Griffey to seventh. Although he did not think he deserved the demotion, Griffey kept his feelings to himself. He hit a two-run double as the Reds won the first game, 8-3. Batting lower in the order, Griffey was not restrained from stealing bases. He led off the sixth inning of Game Two with a single. He stole second base. He stole third base. He danced off third base. Ken Brett, the left-handed Pittsburgh pitcher flinched. The umpire called a balk, sending Griffey home. The Reds won, 6-1. Griffey’s speed was instrumental in winning Game Three. The score was tied in the tenth inning. Leading off the frame, Griffey startled the Pittsburgh defense by dropping a two-strike bunt in front of the plate and beating the throw to first base. He advanced to second on a balk by Ramon Hernandez, moved to third on a groundout by Geronimo, then scored the lead run on a sacrifice fly by pinch-hitter Ed Armbrister. The Reds added an insurance run and held the Pirates scoreless in the bottom of the tenth to win, 5-3, completing the sweep of the series. In the three games Griffey had four hits, scored three runs, batted in four, and stole three bases.

After the Reds lost the first game of the World Series to Boston, they trailed 2-1 heading into the ninth inning of Game Two. The Reds rallied for two runs, capped by a tie-breaking double by Griffey that proved to be the winning hit. In Game Seven he scored the tying run in the seventh after walking, stealing second, and scoring on a single by Rose. With the game still tied in the ninth, Griffey again walked, reached second on a sacrifice bunt, and scored what proved to be the winning run on a single by Morgan. In the seven games Griffey finished 7-for-26 (.269) with three doubles and a triple.

In 1976 Griffey had perhaps his best year at the plate, hitting .336 with an on-base percentage of .401, and tallying 111 runs, 74 RBIs, and 34 steals. Going into the last days of the season Griffey was locked in a duel for the batting title with Bill Madlock of the Chicago Cubs. Griffey was playing nearly every day, while Madlock was allegedly picking his spots, and sitting against tougher opponents. With the division already clinched, several of Kenny’s teammates urged him to protect his thin lead by taking a few days off. Anderson left the decision up to the player, though telling him that playing was the manlier thing to do. Griffey played. On the last day of the season he was hitting .338 to Madlock’s .333. If Kenny did not play Madlock would have to go 4-for-4 to catch him. Anderson now suggested that Griffey should sit, which he did. During the Reds game against the Braves, the Reds received reports that Madlock had gone 4-fo-4 and was now leading the race for the batting championship by one-thousandth of a percentage point. Griffey needed to get into the game. Anderson sent him in as a pinch-hitter and kept him in the game for a second at-bat, but Griffey struck out each time. Madlock won the title, .339 to .336.

The Reds repeated as National League and World Series champions in 1976, sweeping the Philadelphia Phillies in the NLCS and the New York Yankees in the World Series. Griffey hit .385 in the playoffs, though just 1-for-17 in his return to the Series. After the season, The Sporting News named him to their NL All-Star team.

After the championship years, Griffey played five more seasons in Cincinnati and remained a consistently excellent performer. In 1977 he scored a career-high 117 runs, second in the National League, and hit .318. In these four years with the Reds he averaged .300 in 500 games. He made his third All-Star team in 1980, and won the game’s MVP award for his 2-for-3 performance, which included a home run off Tommy John. After the 1981 season Cincinnati traded Griffey to the Yankees for two prospects, a poor trade for the Reds.

Although Griffey’s years as a star were behind him, he still had many years as a contributing player ahead of him. He played semi-regularly for 4½ years for the Yankees, batting .285 with extra-base power and good defense in the outfield. In June 1986 he was traded to the Atlanta Braves for outfielder Claudell Washington and infielder Paul Zuvella and continued to hit well as a platoon outfielder. In August 1988 the 38-year-old returned to Cincinnati, where he was the fifth outfielder, occasional first baseman, and a pinch-hitter into the 1990 season.

In late August 1990 Griffey was released by the Reds and was quickly signed by the Seattle Mariners. In Seattle Griffey made history, as he played on the same team with his son, Ken Griffey, Jr. On August 31, against the Royals, the duo played together for the first time, and hit back-to-back singles in the bottom of the first. On September 14 at Anaheim they did even better, hitting back-to-back home runs off Kirk McCaskill. Griffey Sr. hit .377 over the final month of the 1990 season, good enough to get invited back the next year as a 41-year-old. In the final 85 at-bats of his career, often playing beside his son, he hit .282.

Perhaps in reaction to the neglect he received from his own father, Griffey has taken a great interest in the fortunes of his sons, Junior and Craig. When Junior and Senior were together on the Mariners, the father said, “A lot of times I’d look over to center field, and this is no lie, I still see the hat too big for his head, a baggy uniform, and he’s got number 30 across his chest and back. That’s a father-son game I was remembering when he was just a little kid and I was with the Reds. … Relationships between fathers and sons are unique and different in certain ways.”5

Ken and Alberta “Birdie” Griffey were married young. Junior was born soon after his 19-year-old father had been drafted by the Cincinnati Reds. Junior and Birdie accompanied Griffey to his various minor-league locales, but Junior’s memory goes back only to Cincinnati. Contrary to stories that Junior had the run of the clubhouse, his mother said he was allowed in only after victories.6 A second son, Craig was born in 1971, and the two sons are equal in their father’s affection. Craig played in the minor leagues for seven seasons, reaching the Triple-A level briefly before retiring in 1997. Junior had a long and distinguished career in the major leagues and is almost certainly headed for the Hall of Fame.

The athletic genes that were passed down from Buddy Griffey to the two Kens and Craig have not lost their potency. In 2012 Junior’s son, Trey, accepted a scholarship to play football at the University of Arizona. As with other members of the family, Trey’s greatest asset may be his speed. At his high school in Florida he played both wide receiver and safety. (Craig’s speed had helped him earn a football scholarship as a defensive back at Ohio State University before he left the Buckeyes to play professional baseball.)

As of 2012 Ken and Alberta lived in Winter Garden, Florida. He was inducted into the Cincinnati Reds Hall of Fame in 2004. In 2010 Griffey was the batting coach for the Dayton Dragons, the Reds’ affiliate in the Low A Midwest League. In 2011 he was named manager of the Bakersfield Blaze, the Reds’ farm in the High A California League, and was rehired for the 2012 season.

Last revised: July 1, 2013

This biography is included in the book “The Great Eight: The 1975 Cincinnati Reds” (University of Nebraska Press, 2014), edited by Mark Armour. For more information, or to purchase the book from University of Nebraska Press, click here.

Notes

1 Joe Posnanski, The Machine (New York: William Morrow, 2009), 151-153. Posnanski also wrote that Griffey could not hit a lick in high school. That statement stands in stark contrast to accounts in area newspapers at the time crediting Griffey with game-winning home runs and triples, among other hits.

2 Joe Morgan and David Falkner, Joe Morgan: A Life in Baseball (New York; W.W. Norton & Co., 1993), 195.

3 Posnanski, 154.

4 Posnanski, 210.

5 Bob Sherwin, “Griffey Gap: Model Father Bitter at Own Dad—Ken Sr. Can’t Forget Abandonment,” Seattle Times, October 7, 1990.

6 Ibid.

Full Name

George Kenneth Griffey

Born

April 10, 1950 at Donora, PA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.