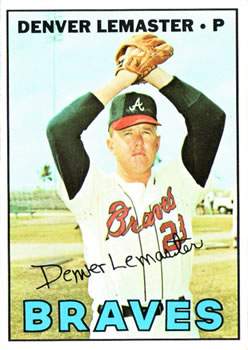

Denny Lemaster

In his debut as manager of the Atlanta Braves on August 9, 1966, Billy Hitchcock sent 27-year-old left-hander Denny Lemaster to the mound against one of the greatest pitchers of all time, future Hall of Famer Sandy Koufax. Before what then the largest crowd at Atlanta Stadium (52,270), Lemaster was every bit the equal of the Los Angeles Dodgers great as he carried a no-hitter into the eighth inning. If not for a ninth-inning walk-off home run by another future Hall of Famer, Eddie Mathews of the Braves, the two lefties appeared to be destined to battle in extra innings before the Braves emerged as 2-1 winners. Plagued by arthritis in his pitching elbow, Koufax retired from as a player after the season, and it was this very same Denny Lemaster who was touted to replace him as the best left-handed hurler in the National League.1 Certainly high praise for any pitcher, lefty or righty, but there was plenty of evidence to support this theory.

In his debut as manager of the Atlanta Braves on August 9, 1966, Billy Hitchcock sent 27-year-old left-hander Denny Lemaster to the mound against one of the greatest pitchers of all time, future Hall of Famer Sandy Koufax. Before what then the largest crowd at Atlanta Stadium (52,270), Lemaster was every bit the equal of the Los Angeles Dodgers great as he carried a no-hitter into the eighth inning. If not for a ninth-inning walk-off home run by another future Hall of Famer, Eddie Mathews of the Braves, the two lefties appeared to be destined to battle in extra innings before the Braves emerged as 2-1 winners. Plagued by arthritis in his pitching elbow, Koufax retired from as a player after the season, and it was this very same Denny Lemaster who was touted to replace him as the best left-handed hurler in the National League.1 Certainly high praise for any pitcher, lefty or righty, but there was plenty of evidence to support this theory.

Eight years earlier, in 1958, Lemaster had been one of 17 California youngsters signed by major-league clubs within a five-week period. Each of these prospects secured sizable bonuses, and among them were future Cubs ace Dick Ellsworth and slugger Ron Fairly. Lemaster signed with the reigning world champion Milwaukee Braves, and the Oxnard High School phenom was soon garnering accolades as the successor to the team’s left-handed ace, Warren Spahn.

Denver Clayton “Denny” Lemaster was born on February 25, 1939, in Corona, California, about 50 miles southeast of Los Angeles. He was the first of two children of Cyrus and Mildred Lee (Wininger) Lemaster. A native of Missouri, Cyrus moved the family to Willard, Missouri, to run the farm he’d grown up on, but when this proved unprofitable, the family returned to California when Denny was about 8 years old. Growing up in Oxnard, California, northwest of Los Angeles, young Denny developed pitching accuracy throwing rocks at fenceposts.

Denny starred as a pitcher at Oxnard High School (which has produced two other major leaguers, Ken McMullen and Paul McAnulty). A score of no-hitters and eye-popping strikeout totals attracted a great deal of attention, and 55 years later Lemaster distinctly recalled coming home after his high-school graduation ceremony and being greeted by 15 major-league scouts (the only team not represented was the nearby Dodgers). Johnny Moore, a longtime Braves scout known for signing such notables as Eddie Mathews, Del Crandall, and Lee Maye, prevailed with a reported $70,000 bonus. (Lemaster remembered Moore as “a true gentleman’s gentleman.”)

The 19-year-old trekked over 2,000 miles to report to his first professional assignment, at Eau Claire (Wisconsin) in the Class C Northern League. The 1958 Eau Claire Braves led the league in home runs and batting average, but the pitching staff had a middling 4.31 earned-run average, greatly enhanced by Lemaster’s 2.82 ERA in limited work (he joined the team midway through the season). It was sufficient exposure for Milwaukee to invite him to spring training in 1959.

Something besides Lemaster’s growing reputation produced this speedy invite. The Braves had made another World Series appearance in ’58, but had done so with an aging pitching staff anchored by 37-year-old Warren Spahn. The Braves had to develop replacements quickly in anticipation of Spahn’s waning years, and Lemaster was one of six pitchers from Class B or lower whom the club chose to examine closely.

Whatever the Braves brass saw, it was enough to warrant a promotion from Class C to Jacksonville in the Class A South Atlantic League. There Lemaster joined a team far more proficient on the mound than at the plate. He raced to a 7-4, 2.58 mark to start the campaign, but a dismal second half resulted in a less inviting 11-17, 3.56 at the close. Of further concern was Lemaster’s wildness, a trend foreshadowed in the Northern League that came to full exposure as Lemaster led the South Atlantic League in walks with 122 (6.4 per 9 innings). But he was also among the leaders in strikeouts (150) and had a league-record 11 consecutive whiffs in one game.

Lemaster’s second-half collapse did not dissuade the Braves from promoting him again in 1960, for after another brief exposure in spring training he found himself hurling for the Austin Senators in the Double-A Texas League. A 14-6 record for a club that finished close to .500 was accompanied by a variety of other postings that placed him among the league leaders in winning percentage (.700), complete games (13), innings pitched (198), and strikeouts (181). The walks continued, but Lemaster was able to shave this figure slightly to 5.7 per 9 innings pitched, a figure that diminished further in each of his two remaining minor-league campaigns.

The Braves gave Lemaster a much longer look the following spring. In an effort to bolster their middle infield defense, Milwaukee had traded away three prized young pitchers, Joey Jay, Juan Pizarro, and Terry Fox, for infield defense, and Lemaster and future Hall of Famer Phil Niekro were two of a small corps of youngsters examined closely to fill the void. The Braves Bob Hendley and Don Nottebart, who had Triple-A experience, and Lemaster was assigned to the Vancouver Mounties in the Pacific Coast League.

Under manager Billy Hitchcock, Lemaster struggled early (2-6, 5.09 ERA in 14 appearances). Instead of being demoted he was assigned to the Braves’ other Triple-A affiliate, the Louisville Colonels in the American Association. There he pitched well enough during the remainder of the 1961 campaign and the first half of the 1962 season to warrant a call-up. He won his last eight decisions in the American Association with a 1.08 ERA, and matched a league record by striking out seven batters in a row. Lemaster attributed his improvement to a new delivery that improved his control (41 walks in 124 innings). “I opened up with my right leg. … [T]hat gave me more follow-through and now I don’t get tired as fast, either. Before [that] I was throwing across my body – more or less stiff-armed,” he said.2

On July 12 the Braves beckoned and three days later Lemaster made his major-league debut. He acquitted himself well in a complete-game loss to the Cincinnati Reds, surrendering only six hits and two earned runs. Said Milwaukee manager Birdie Tebbetts, “[I]f he keeps pitching like that, he’s going to win a lot of games for this club.”3 The Milwaukee press quickly decided that the heir to Warren Spahn had most likely been found.

On the strength of this debut performance Lemaster made 16 more appearances (11 starts) the rest of the season, finishing with a 3-4 mark that was due largely to a lack of run support.

If Lemaster received a taste of what it was like pitching without much run support in his first exposure to the major leagues, he was soon treated to a continuous diet of it in 1963. Under manager Bobby Bragan, he was used primarily in relief for the first month, and a 1.80 ERA got him returned to the starting rotation. With six straight losses in September he had an 11-14 record, but nonsupport by the batters was again a big factor. On one occasion Lemaster had to take matters into his own hands by hitting a home run against the Pittsburgh Pirates that was the difference in a 2-1 pitching duel. Bested only by Warren Spahn in the last 20-win campaign of his career, Lemaster was among the team leaders in ERA (3.04), starts (31), complete games (10), and innings pitched (237). He set a Milwaukee Braves record for strikeouts with 190, shattering the previous high of 154 set by Spahn in 1960.

Dubbed by the press the Braves’ “Best Young Pitcher”4 and a “Second Spahn,”5 Lemaster entered his second full season with increased confidence and a new pitch, a change-up. After getting outfielder Felipe Alou in an offseason trade, the Braves had considerable pennant hopes entering the 1964 campaign. Those hopes were soon dashed.

A strong 23-10 close to the season could not make up for the miserable summer months when the club fell more than 14 games off the pace. The offense had rediscovered itself, but the pitching went sour. Spahn, the ageless wonder, saw his ERA balloon to an unsightly 5.29, but he was far from alone. If it hadn’t been for the New York Mets, the Braves would have had the worst team ERA at 4.12. The culprit was inexperience. The Braves had disposed of veterans Lew Burdette and Bob Shaw, and over 80 percent of the team’s games were started by pitchers 26 or younger.

Lemaster was not immune to these setbacks; his ERA (4.15) nearly mirrored the team’s. But at last he had healthy run support and finished with a 17-11 record. Two shutouts in September (including a one-hitter against Cincinnati) contributed to a fine close to the campaign, causing teammate Hank Aaron to predict a 20-win season for Lemaster in the future.6 (Illustrative of the high regard in which the lefty was held were similar comments from future Hall of Famers Willie McCovey7 and Joe Morgan8 later in his career.)

On their way north from Florida to inaugurate the 1965 season, the Milwaukee club stopped in Atlanta for a three-game exhibition series, and in one of these games Lemaster became the first winning pitcher (albeit in an exhibition) at Atlanta Stadium. The season itself was played against the realization that the Braves would relocate to Atlanta in 1966, and this three game excursion was a means to showcase themselves. In the season itself, Milwaukee produced a middling fifth-place finish.

The exhibition win in Atlanta was one of Lemaster’s few achievements in 1965. Arm problems contributed to a dismal 4-7 (6.10 ERA) start to the season. Shoulder tendinitis resulted in an extended stay on the disabled list, and later in the season Lemaster said his difficulties actually started in the spring. “My shoulder was stiff then,” he said. “I kept on pitching , but I never really got over it. … [E]very day for 32 days I took cortisone shots and deep heat treatment.”9 To no avail. Lemaster returned to the mound in July, but a 2.80 ERA the rest of the season was not enough to rescue his overall mark (7-13, 4.43). To add further insult, the “Second Spahn” label was soon shifted to another lefty on the staff, Wade Blasingame.

Lemaster was nearly traded to the Detroit Tigers during the season. Several clubs inquired about him and a deal involving Tigers slugger Norm Cash came closest to fruition. But Lemaster’s strong close (including a shutout of the Dodgers in his last appearance) caused the Braves to pull back from any transaction, and they didn’t regret it. Lemaster opened the 1966 season with a 4-2 mark and a 2.04 ERA. The 2-1 verdict over Koufax was followed five days later by a 14-strikeout gem against the Philadelphia Phillies. This accumulated success came to a screeching halt in Lemaster’s next start. A pinched nerve in his left elbow forced him to quit the game after four innings, and Lemaster was idled until Opening Day of 1967.

The eight-month layoff worked wonders. A 7-1 record with a 2.68 ERA resulted in his only selection to the National League All-Star squad, though he didn’t pitch because of a pulled rib-cage muscle suffered a week before the game. His seven victories didn’t include five games in which the Braves bullpen gave up a lead. But Lemaster’s early success did not sustain itself, and his second half was marred by a 2-8 finish, an unsightly 7.57 ERA in the games he lost, and a 9-9 overall record. “It all started with the [rib cage] injury,” Lemaster said. “I tried to push myself too fast. My timing was off, my rhythm gone. I probably wasn’t ready to pitch, but I wanted to try.”10

During the offseason the Braves again found themselves needing middle-infield help. Meanwhile the Houston Astros were trying to improve their pitching. On October 8, 1967, Lemaster and infielder Denis Menke went to Houston in exchange for first baseman Chuck Harrison and shortstop Sonny Jackson. Pitching for Houston, Lemaster was plagued by the same lack of run support that had hampered him in his first full major-league season, 1963. He had added a screwball to his arsenal, and his first six decisions included a masterful three-hit shutout of the reigning world champion St. Louis Cardinals, but the following probably best represents the challenges Lemaster faced while pitching for the last-place Astros: In 15 starts that resulted in no victories and ten defeats for Lemaster, he posted a minuscule 1.96 ERA. Part of this reflects the “Year of the Pitcher” era, when the major-league ERA was 2.98. Lemaster bettered that with a career low 2.81 but wound up with a pedestrian 10-15 mark (the Cardinals’ Nelson Briles had an identical 2.81 ERA but a 19-11 record). With improved pitching but an anemic offense, the Astros began shopping Lemaster in pursuit of a strong bat. Early reports had him going to the expansion Montreal Expos, but no deal was made, and Lemaster continued to ply his trade in Houston.

After the 1968 season major-league baseball moved to even the balance between pitching and offense, and one such move was the lowering of the mound. Many pitchers struggled with the adjustment. Cleveland’s Luis Tiant, for instance, went from a 20-win campaign in 1968 to 20 losses in 1969, but he had plenty of company. By May 10 Lemaster had an unsightly 6.00 ERA, a 0-5 mark, and 14 walks issued in only 30 innings of work. The mound alteration is making “a big difference,” he said. “My foot hits the ground so quick it jars me. All of the pitchers are throwing higher this spring.”11 Lemaster eventually adjusted and was among the Astros’ leaders in wins (13) and ERA (3.16), but the heartbreaking losses also continued to mount – including a 1-0 loss in which he Denny did not yield an earned run and struck out 13 Chicago Cubs. His 173 strikeouts contributed to a then-record 1,221 by the Astros’ pitching corps.

Another adjustment was in store for Lemaster in 1970. He was removed from the rotation in July for ineffectiveness (6-12, 4.61 ERA after 21 starts) and the fact that the team needed support in the bullpen. (A start on July 20 was his last in the major leagues.) Lemaster responded positively to the move. Except for one poor outing in San Francisco near the end of the season, he had a 2.57 ERA in 16 appearances. (His overall positive experience was marred early in the season when he lost two games in one day. Shelled by the Mets in a start in the first game of a doubleheader on May 31, Lemaster pitched again in the second game and gave up an unearned run in the 14th inning to absorb the second loss.)

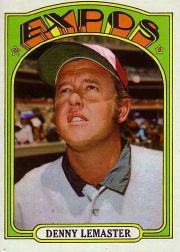

At the age of 32, Lemaster found that he and closer Fred Gladding (age 35) were the only hurlers on the 1971 Astros squad over the age of 28 on an ever-younger staff. He had two saves with a respectable 3.45 ERA, but with the club seemingly in continued pursuit of a younger mound corps, Lemaster was sold by the Astros to the Montreal Expos after the season.

At the age of 32, Lemaster found that he and closer Fred Gladding (age 35) were the only hurlers on the 1971 Astros squad over the age of 28 on an ever-younger staff. He had two saves with a respectable 3.45 ERA, but with the club seemingly in continued pursuit of a younger mound corps, Lemaster was sold by the Astros to the Montreal Expos after the season.

Lemaster hoped that the Expos would have room for him to move back into a starting role. But though the team finished well under .500 in 1972, one of its few strengths of the team was the starting rotation and there was no space for the aging lefty to squeeze into. Montreal actually started the 1972 campaign with five straight wins, with Lemaster getting the last of those with a one-hit performance in three innings. But the wheels soon came off. A handful of dismal outings led to a 7.78 ERA by mid-June, and the Expos released Lemaster on July 1.

Thus the “second Spahn,” the left-handed heir to Sandy Koufax, was (with little fanfare) gone from the game. Periodic accolades aside, Lemaster ended his career with a pedestrian won-lost percentage of .462, but as noted, often the result of a lack of run support. Injuries also took their toll when, for example, Lemaster was forced to sit out the last quarter of the 1966 campaign. The comparison with Nelson Briles in 1968, when the same 2.81 ERA resulted in nine fewer wins for Lemaster, could lead one to speculate how his career might have fared if he played for more successful clubs. His big-league success did not go unnoticed though, as Lemaster was inducted into the Ventura County (California) Sports Hall of Fame 16 years after his last major-league pitch.

Released by the Expos, Lemaster turned a budding profession as a fisherman into a semi-steady line of work. An avid outdoorsman, he had garnered a stake in first place in the Major League Baseball Players All-Star Fishing Tournament as far back as March 1966, with a specialization in clear-water fishing. This outdoor passion extended to hunting as well, as he was known to have gone in pursuit of dove in South Texas with longtime teammate Wade Blasingame.

Lemaster returned to Atlanta, where he and his wife, Earlene, were raising their four children when tragedy struck – Earlene was killed in a car accident in the mid-’70s. In 1983 Denny was remarried. He spent 32 years in the homebuilding field. In early 2013, Denny and Barbara “Bunny” Lemaster enjoy 14 grandchildren and four great-grandchildren. (One of the grandchildren, 19-year-old Clay Garner, apparently carried Denny’s baseball genes and was attracting major-league attention. Garner hoped to wear the same uniform number – 23 – that his grandfather actively sought and wore from high school and throughout his major-league career.)

Participation in a bass tournament in the 1970s at Elijah Clark State Park, in northeastern Georgia, led to a permanent residence nearby. Then, through the instigation of his wife Bunny, Denny took up woodcarving in the 1980s, and became an accomplished wildlife artist. In a manner of speaking, his life came full circle: An arm developed from throwing rocks at wooden fence posts led to a successful major-league career, and Lemaster now uses his hands to develop wildlife carvings made from wood. Had it not been for those same tempting wooden targets of his youth, Lemaster might never have matched up so well against Sandy Koufax that summer night in Atlanta so many years earlier.

Postscript

Denny Lemaster died at the age of 85 on July 24, 2024.

Acknowledgments

The author wishes to thank Denny Lemaster for the hour-long telephone conversation on January 16, 2013, that helped to ensure the accuracy of this biography.

Sources

http://likethedew.com/2011/09/04/denny-lemaster-master-wildlife-carver/

http://articles.latimes.com/keyword/denny-lemaster

Notes

1 “New Koufax? Braves Backing Denny,” The Sporting News, April 1, 1967, 5.

2 “Braves’ Search for Spahn Heir Turns Up Prize Portable Pair,” The Sporting News, July 28, 1962, 28.

3 Ibid.

4 “N.L. Writers Make Their Picks,” The Sporting News, April 25, 1964, 12.

5 “Braves Preen Head Feathers Over ‘Second Spahn’ Lemaster,” The Sporting News, April 11, 1964, 29.

6 “Aaron Sees Braves’ Flag Final Year in Milwaukee,” The Sporting News, January 30, 1965, 7.

7 “Stretch Proved His Point – Whacked Lefties,” The Sporting News, November 19, 1966, 33.

8 “Sonny Will Shine, Says Pal Joey,” The Sporting News, December 30, 1967, 43.

9 “Lefty Lemaster – Big Mound Bonus for Braves,” The Sporting News, August 28, 1965, 5.

10 “Lemaster Collapse Bugging Braves – A Mystifying Flop,” The Sporting News, August 26, 1967, 10.

11 “Pitchers Moan, Batters Skeptical of Low Hill,” The Sporting News, March 29, 1969, 8.

Full Name

Denver Clayton Lemaster

Born

February 25, 1939 at Corona, CA (USA)

Died

July 24, 2024 at Monroe, GA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.