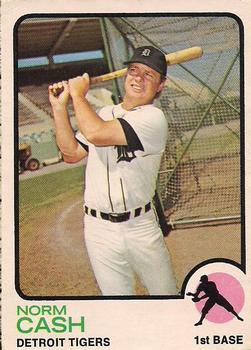

Norm Cash

Norm Cash would have loved it. The story drew upon metaphors including baseball, the Old West, and the camaraderie of friends. Its title,

Norm Cash would have loved it. The story drew upon metaphors including baseball, the Old West, and the camaraderie of friends. Its title, City Slickers, was evocative of the relationship between the burly cowboy and the legions of brewers, auto manufacturers, and teamsters who became his fans. The director, Billy Crystal, who also played the protagonist Mitch Robbins, later filmed a motion picture about the 1961 American League baseball season at Tiger Stadium. In a poignant scene, an elderly cattle driver named Curly, played by Jack Palance, teaches Mitch the meaning of life. Moments later, “Mitchy the Kid” delivers a calf, who he names Norman. Sadly, Norm Cash never had the opportunity to see City Slickers. It was released in theaters in 1991, five years after he drowned in a tragic boat accident. But just who was Norm Cash? He was a larger than life first baseman from Texas who lived, drank, and played hard, sang country and western in the clubhouse, and could be depended upon in clutch situations. This is his story.

City Slickers, was evocative of the relationship between the burly cowboy and the legions of brewers, auto manufacturers, and teamsters who became his fans. The director, Billy Crystal, who also played the protagonist Mitch Robbins, later filmed a motion picture about the 1961 American League baseball season at Tiger Stadium. In a poignant scene, an elderly cattle driver named Curly, played by Jack Palance, teaches Mitch the meaning of life. Moments later, “Mitchy the Kid” delivers a calf, who he names Norman. Sadly, Norm Cash never had the opportunity to see City Slickers. It was released in theaters in 1991, five years after he drowned in a tragic boat accident. But just who was Norm Cash? He was a larger than life first baseman from Texas who lived, drank, and played hard, sang country and western in the clubhouse, and could be depended upon in clutch situations. This is his story.

Norman Dalton Cash was born on November 10, 1934, in Justiceburg, Texas. A railroad junction located southeast of Lubbock, Justiceburg boasted a population of 25 according to the 1925 population census. Fittingly, its most famous citizen wore 25 as his uniform number for most of his professional baseball career. Cash’s most dominant childhood memories were of helping on the family farm: “My dad’s life was hard work…he had 250 acres of fertile land and we grew cotton on 200 acres. I drove a tractor from the time I was ten. Sometimes I drove it ten to twelve hours.”1

Working with a hoe on the farm also allowed him to develop his wrists. Ironically, those who knew Cash during his youth remember his athletic abilities, not on the baseball diamond but on the football gridiron. In 1955, during his senior year at Sul Ross State College in San Angelo, he set the school rushing record with 1,255 yards. Following graduation, Cash was even drafted in the 13th round as a halfback by the Chicago Bears. Instead, he chose baseball, signing with the Chicago White Sox as an outfielder on May 21, 1955. Meanwhile, Cash had married his childhood sweetheart, schoolteacher Myrta Bob Harper, on January 24, 1954.

After two seasons at Ft. Bliss, the left-handed hitter and fielder was promoted to Comiskey Park midway through the 1958 season. Cash was soon converted to a first baseman, and after some seasoning at Indianapolis, he was recalled by the White Sox in 1959. Playing backup to Earl Torgeson, Cash batted only .240 but fielded a stellar .993 in 31 games. The White Sox, led by speedy infielders Luis Aparicio and Nellie Fox, raced to the summit of the American League standings, hitting 46 triples and stealing 113 bases in 94 victories. The “Go-Go Sox” outdistanced second-place Cleveland by five games to capture their first pennant in 40 years. However, the Sox were badly overmatched by the Los Angeles Dodgers, losing the World Series in six games. Much like their 1906 predecessor, the ’59 incarnation of the White Sox were, indeed, hitless wonders. Not even late season acquisition Ted Kluszewski could save the Sox from their 97 aggregate home runs and anemic .250 batting average. During the offseason, President Bill Veeck acquired veteran Roy Sievers, Gene Freese, and Minnie Minoso to bolster Chicago’s offense. However, he was forced to mortgage his future prospects, including Earl Battey, Don Mincher, Johnny Callison — and Norm Cash. No match for Kluszewski and Torgeson, Cash was sent to Cleveland with Bubba Phillips and Johnny Romano in the seven-player Minoso deal on December 6, 1959.

Although Cash wore a Cleveland cap on his 1960 Topps baseball card, he never played an inning for the Indians. On April 12, as the Tribe headed north from Tucson at the conclusion of spring training, Cash found himself traded yet again. This time, he was dispatched to Detroit in exchange for outfielder Steve Demeter. Detroit general manager Rick Ferrell was dumbfounded when Frank Lane, his Cleveland counterpart, offered Cash for Demeter, unsure if he meant “cold cash or Norm Cash?”2 While Demeter’s career with the Indians consisted of merely four games, Cash became a fixture at first base in Detroit for 15 years. Lane was not through making controversial trades with the Tigers. Five days later, he sent Rocky Colavito to Michigan for Harvey Kuenn, and later in 1960, the two clubs swapped managers, Joe Gordon for Jimmie Dykes.

Cash’s teammates took an immediate liking to him. A comedian both on the field and in the clubhouse, he once tried to call time after being picked off first base. In another instance, Cash was stranded on second base during a thunderstorm. Once play resumed, however, he returned to third base. The umpire was baffled.

“What are you doing over there?”

“I stole third,” he answered.

“When did that happen?”

“During the rain.”3

On several occasions, he gave a muddy infield ball to the pitcher instead of the game ball so the hitters could not see it as well. Al Kaline remembers:

“Whenever you mention Norm Cash, I just smile. He was just a fun guy to be around and a great teammate. He always came ready to play. People don’t know this, but he often played injured, like the time he had a broken finger.”4 Sonny Eliot, Detroit’s ageless wacky weather man, describes Cash as “just old fashioned likeable,” comparing his physical form to a kewpie doll from a state fair. “Whenever he came to bat, I would yell ‘Hey kewpie doll,’ and he’d turn around and laugh.”5 It was another Southerner and recent transplant to Detroit who presented Cash with his nickname: “I was in Baltimore [for six years] and there was a fellow there named Norman Almony,” remembers Ernie Harwell. “Everybody called him Stormin Norman. When Norman Cash lost his temper once in a while, I gave him the nickname Stormin Norman. I don’t think he liked it at first, but after a while, he started treasuring it.”6

After a respectable 1960 season in which he batted .286 with 18 home runs, Cash captured the baseball world by storm in 1961. Although playing in the shadow of Mickey Mantle and Roger Maris, Cash posted one of the most outstanding offensive single season records in American League history. Stormin’ Norman led the junior circuit with 193 hits and a .361 batting average. Number 25 also established personal marks of 41 home runs, 132 RBIs, and eight triples. Even more astounding, he hit .388 on the road! Facing Washington’s Joe McClain on June 11, Cash became the first Detroit player to clear the Tiger Stadium roof, hitting a home run that landed on Trumbull Avenue. Another against Boston’s Don Schwall struck a police tow truck. He was equally skilled at first base, fielding a sterling .993 as he caught dozens of long foul balls before they could fly into the stands. With Kaline’s .324 batting average and Colavito’s .290 complementing Cash in the lineup, the Tigers, led by Frank Lary and his 23 victories, challenged the Yankees for the American League pennant. The Bengals came within a game and a half of the Bronx Bombers on September 1 before retracting to finish eight behind in the standings with 101 victories.

Was Norm Cash destined to become a one-year wonder? Even at the time, he knew his ’61 season was a freak, saying that everything he hit seemed to drop in, even when he didn’t make good contact. After Frank Lary injured his leg on Opening Day and Al Kaline broke his shoulder during a nationally televised game in May, it became clear that the Tigers would not again challenge the Yankees in 1962. The season was equally disappointing for Cash, who batted only .243 for the season. The 118 points shaved from his average remains a record of futility among batting champs. Cash ultimately found his swing, batting .342 in an autumn exhibition trip to Japan, but by that point, the regular season was long over. Still the 1962 season was far from a write-off for the affable Texan. Cash hit 39 home runs, including three more roof shots, as the league runner-up to Harmon Killebrew’s 48. His .993 fielding percentage was identical to his 1961 average.

Cash never again cracked the .300 plateau. Years later, when Mickey Lolich asked why, he replied that “Jim Campbell pays me to hit home runs.”7 Indeed, Cash’s 373 home runs for the Tigers remains second only to Al Kaline’s 399 among aggregate team records. However, it soon became evident that other factors besides the maturation of expansion pitching compromised Stormin’ Norman’s batting average. Cheating in baseball was as much an issue in 1961 as it remains today, and Sonny Eliot remembers why Norm Cash called that season “the Year of the Quick Bat.”

“We used to sit in the old Lindell’s A.C.,” said Eliot, referring to the popular watering hole adjacent to Tiger Stadium. “We’d just rib the hell out of him. ‘Did you put cork in the bat? If not cork, was it lead?’ Or whatever it was, we’d just rib him.”8 He struck out frequently, and fans expecting another batting title consistently booed cash for the balance of his career. Even his wife joined in the chorus on occasion.9 Stormin’ Norman knew that inherently, they were as good natured as he was. After all, when Mayo Smith removed Cash from the lineup during a slump, the manager was also

booed.10 Although he was not bothered by the sounds of tens of thousands of boos, “when one or two guys get on your back, they drive you nuts.”11 For their appreciation of his congeniality and humor, the Tigers Fan Club crowned Cash as King Tiger in 1969. George Cantor described Cash as “the most popular man on the team,” who knew “all the best watering holes” throughout the American League.12

Although Cash stifled the cork in 1962 and thereafter, he sound found himself fighting a much larger battle in alcoholism. Denny McLain described his roommate as “a modern medical miracle,” who abused his body so mercilessly that he “should [have turned] it over to the Mayo Clinic.”13 Stormin’ Norman violated every curfew rule in the book, but he somehow arrived at the ballpark every day, “not only eager to play, but madder than hell if he didn’t.”14 Granted, Cash rarely showed up on time: he “could not make 9:00 am workouts because he threw up until 10:00 am.”15 McLain credited hustle and determination as the secret to Cash’s big league longevity, although the bespectacled righthander did admit that he was often bewildered “how he managed to remain upright” when he took the field. Still, McLain admitted that “I always felt better about everything when I looked over and saw Stormin’ Norman at first base.”16 Players were rarely unanimously accepted by their peers, but Cash proved an exception. As pitcher Jerry Casale once conveyed, “on a team with so many friends, there was no one nicer than Norm Cash.”17

Cash was nothing if not consistent for the balance of the 1960s. He was the only American League hitter to slug 20 or better home runs each year from 1961 to 1969. In 1964, he set a record among Detroit first baseman by fielding an outstanding .997. On July 9, 1965, Stormin’ Norman hit an inside-the-park home run against the A’s at Municipal Stadium in Kansas City. The blast must have ignited Cash’s non-corked bat, as he decimated American League pitching with 23 home runs and 58 RBIs in 78 games after the All-Star break. His second-half exploits earned him Comeback Player of the Year honors, and in 1966, he was invited to the All-Star Game. Cash, once again, led junior circuit first basemen in fielding with a .997 percentage. Meanwhile, the Cash family was expanding, as Norm and Myrta welcomed son Jay Carl on April 28, 1963, and daughter Julie Lee on December 28, 1964.

Stormin’ Norman proved to be the exception on the 1968 Tigers as he was fighting an early season slump. On July 27, the 6-foot-0 Cash was barely hitting his weight, batting .195 on a team cruising to its first American League pennant in 23 years. In dramatic fashion, he hit a torrid .333 in his last 54 games to finish the season at .263. Included in his 12 home runs and 33 RBIs in August and September was a three-run blast against Oakland on September 14. The winning pitcher of the 5-4 decision was Denny McLain, his 30th of the season. Cash led Tigers batsmen in the World Series, hitting .385 against Cardinals pitching. Setting a dubious October record as Bob Gibson’s 16th strikeout in Game One, he redeemed himself the following afternoon, homering off Nellie Briles in an 8-1 complete-game victory for Mickey Lolich. Facing elimination in Game Six, Cash enjoyed another productive day at the plate, accounting for two of the 13 Detroit runs, tying the Series at three games. This set the stage for an historic Game Seven. The Tigers were unfazed at the prospect of facing a pitcher who specialized in winning Game Sevens, Bob Gibson. In the clubhouse after practice, manager Mayo Smith encouraged his players that Gibson “can be beat, he’s not Superman!” To this, Cash chimed “Oh yeah? Just a little while ago, I saw him changing in a phone booth!”18 Tigers hitters proved to be Kryptonite with two outs and no score in the seventh inning. Cash ignited a Detroit rally with a single off Gibson, and later put the Tigers ahead as the first runner to score on Jim Northrup’s triple. The final score was 4-1, and the Detroit Tigers were world champions.

After being relegated to pinch hitting in 1970, Cash enjoyed a renaissance season playing in the Renaissance City in 1971. So torrid was his first half that spectators across Major League ballparks voted him to start the All-Star Game on July 13. Played in Detroit, it drew 53,559 spectators. American League manager Earl Weaver, however, took exception to Cash’s assignment, as he was not the reigning MVP playing for the defending World Champions. Boog Powell, Weaver’s first baseman in Baltimore, could claim both. Accordingly, Weaver, scrapped Cash from the lineup and replaced him with Powell. The roster move was not kindly received by the Detroit faithful. After public address announcer Joe Gentile introduced the National League All-Stars were announced, he began to present the American League. Starting with Weaver! Again, a cloud of boos rained over Tiger Stadium. Although Rod Carew was the next to be announced, the Twins’ second baseman did not take his place when called. Carew was apprehended by Cash and Bobby Murcer to prevent him from leaving the dugout, thereby prolonging the catcalls. Only after a prolonged interval did Carew emerge, breaking up the hecklers.19

When the dust cleared on the 1971 season, the Tigers had won 91 games, but finished 10 games behind Earl Weaver and the Orioles. Stormin’ Norman clubbed 32 round trippers — one shy of Bill Melton’s league lead — while driving in 91 runs, batting a respectable .283. His offensive record was enough to win his second American League Comeback Player of the Year Award. It would have surprised nobody to hear Cash proclaim, after accepting the honor, that he hoped he would win the award again next year. Cash was, however, named to the All-Star team once again in 1972, his fourth and final trip to the midsummer classic. is offensive output may have retracted, but the Tigers vaulted ahead in the standings to win their first American League East Division title.

A player known for his pranks, Cash saved his most famous stunt for the twilight of his career. It occurred on July 15, 1973, as the Tigers entertained the visiting California Angels. Not one Detroit batsman had hit safely off starting pitcher Nolan Ryan. With two away in the bottom of the ninth, the Ryan Express had already fanned 16 as his Angels led, 6-0. Potentially the final hitter of the game, Norm Cash strode to the plate substituting a table leg for a bat. Home plate umpire Ron Luciano forbade Cash’s creative use of equipment. Cash protested, “But Ron, I’ve got as much chance with this as I do with a bat.”20 As Jim Northrup remembered from the third base dugout, Cash reluctantly retrieved a bat and struck out on three pitchers against his fellow

Texan. The no-hitter was Ryan’s second in as many months; as Cash returned to the dugout, he turned to Luciano and expressed, “See, I told ya.”21

The 1974 season was a transitional one for the Tigers and their personnel. For only the second time in franchise history, Detroit finished the season in last place. Stormin’ Norman no longer held the nomenclatural monopoly when youthful infielder Ron Cash joined the Tigers in spring training. Equipment manager John Hand wanted to change the name on Norm’s uniform, but the first baseman refused. Cash exclaimed in disgust, “If the people can’t tell the difference between me and the other guy, something’s the matter!”22 He became even more incensed when he received a telephone call from the general manager on August 7. Batting only .228 with 12 home runs and 12 RBIs, Cash was released. “I thought at least they’d let me finish out the year. Campbell just called and said I didn’t have to show up at the park.”23

Norm Cash was a player who knew his baseball career would not last forever. As a player, his offseason occupations included banking, ranching, and auctioning hogs. In the early 1970s, Cash hosted a local variety show in Detroit called “The Norm Cash Show.” In 1976, he teamed with former October archrival Bob Gibson as broadcasters for ABC Monday Night Baseball. Although Cash continued to display his brand of humor, it was not appreciated by all. On-air remarks such as equating entertainment in Baltimore with going “down to the street and [watching] hubcaps rust” earned Cash his dismissal from the network.24 In 1978, he made his film debut with a cameo appearance in One in a Million: The Ron LeFlore Story. In a scene filmed at Lakeland, Cash was standing with Kaline, Bill Freehan, and Northrup to watch LeFlore in first spring training after accepting his release from Jackson State Prison. When the others marveled at his speed, Cash chimed in with “He can’t be too fast, the cops caught him.”25

Now divorced from Myrta, Cash married his second wife Dorothy on May 22, 1973. They moved upstate from Detroit, first to Union Lakes, where Cash worked as a sales representative for an automobile machinery manufacturer. When asked, Cash remarked that “it’s good money…but to tell the truth I’m looking for something else to do.”26 Sadly, the good times were short-lived. As Detroit automakers proved to be no competition for Japanese imports, Cash’s financial windfall proved to be short term. His health began to deteriorate, suffering a massive stroke in 1979. As Ernie Harwell remembers, Cash was out of commission for quite a while. Fortunately, by 1981 he was healthy enough to broadcast Tigers games for the ON-TV cable network. He and Hank Aguirre provided color commentary alongside Larry Adderly’s play-by-play. By 1983, partial paralysis of his face made him slur his words and he could no longer continue. In 1986, Cash returned to Tiger Stadium to participate in the Equitable Old Timers’ Game. Fans were shocked to see the first baseman a shadow of his physical self. He could no longer field routine infield balls, as a throw from third base hit him in the head before bouncing away. Cash handled the situation with humor, but privately, he was embarrassed by the incident.27 What nobody realized at the time is that the appearance would be his last at the corner of Michigan and Trumbull.

Scott McKinstry remembers Sunday evening of the Columbus Day weekend being a grey, misty one. “I was standing at the lighthouse…on Lake Michigan looking out over the water to where boats head out from Charlevoix to Beaver Island.”28 The weather forecast echoed the somber mood to be shared by Tigers fans in unison. Earlier in the day, Cash left his condominium to meet Dorothy and a friend for dinner at the Shamrock Bar on Beaver Island. Those present could affirm that Cash had been

drinking.29 After dinner, he returned to the dock to check on his boat after dinner. Unable to navigate the slippery pier in cowboy boots, he fell into the water and could not pull himself out.30 The next morning, he was found floating in 15 feet of water in St. James Bay.31 Norman Dalton Cash was pronounced dead on October 12, 1986. He was 51 years old. Tragedy would hit the Cash family a second time in 1987 when Norm’s son Jay committed suicide.32

Like Buddy Holly before him, the Texas legend of Norm Cash lives on. Ernie Harwell recalls receiving an autographed photo from Cash inscribed with his trademark humor, “to the second-best broadcaster in the big leagues. The other 25 tied for first place.”33 Gary Peters, who broke in with the White Sox concomitantly with Cash, remembers his diverse collection of hobbies which included horseback riding, fencing, waterskiing, dancing, and playing the ukulele.34 Whitey Herzog, Cash’s roommate in 1963, once claimed that “there was nothing Norm Cash couldn’t do.” Describing Cash as his roommate, however, might have been an exaggeration; Herzog recalls the experience as “just like having your own room.”35 On April 23, 2005, the sandlot in Post, Texas where Stormin’ Norman played Little League, was rededicated in memory of Garza County’s most famous athlete as Norm Cash Field.

Perhaps the most vocal and outward posthumous tribute to Norm Cash in the final hours of the ballpark whose first base he called home from the Eisenhower to the Nixon administration. A sellout crowd of 43,556 jammed Tiger Stadium on September 27, 1999 for the final game against the Kansas City Royals. Several Tigers switched uniform numbers to pay homage to players who passed before them. Paying tribute to Ty Cobb, Gabe Kapler did not wear any number at all. Rookie Rob Fick switching his number 18 for 25 to honor Norm Cash. Only Fick went one step further. The Tigers enjoyed a comfortable 4-2 eighth-inning lead when Fick crushed a Jeff Montgomery fastball for a grand slam home run. In true Norm Cash fashion, the ball nearly cleared the right field roof. Tom Stanton reports in The Final Season, a diary which paints Tiger Stadium as a metaphor for the bond between fathers and sons, that Fick “looked up in the sky and thought of my dad,” who passed away the year before. “I know that he had something to do with all this.”36

So did Norm Cash.

An earlier version of this biography originally appeared in SABR’s “Sock It To ‘Em Tigers: The Incredible Story of the 1968 Detroit Tigers” (Maple Street Press, 2008), edited by Mark Pattison and David Raglin. It also appeared in SABR’s “Go-Go To Glory: The 1959 Chicago White Sox” (ACTA, 2009), edited by Don Zminda.

Sources

In addition to the sources cited in the Notes, the author also consulted www.baseball-almanac.com, www.baseball-reference.com, www.imdb.com,and the following:

“Lobos Fall in Season Finale; Barber Breaks 1,000 Yard Mark” in The Sul Ross Skyline (16 November 2006): 18 pars. [Journal Online]. Available from http://www.sulross.edu/pages/3998.asp. Internet. Accessed 6 April 2007.

“Norm Cash.” Brooklyn: Topps Chewing Gum Inc., 1960: 488.

Barnes, Tyler. Detroit Tigers 1999 Information Guide (Detroit: Tigers Public Relations Department, 1999).

Barnes, Tyler. The Inaugural Season: Detroit Tigers 2000 Information Guide (Detroit: Tigers Public Relations Department, 2000).

Cohen, Irwin. Tiger Stadium (Charleston, South Carolina: Arcadia Publishing, 2003).

Dewey, Donald, and Nicholas Acocella. Total Ballclubs: The Ultimate Book of Baseball Teams (Toronto: Sport Classic Books, 2005).

Hunt, William. “Justiceburg, Texas” in The Handbook of Texas Online (2001): 2 pars. Available from http://www.tsha.utexas.edu/handbook/online/articles/JJ/hnj13.html. Internet. Accessed 6 April 2007.

Lyons, Jeffrey and Douglas B. Curveballs and Screwballs: Over 1,286 Incredible Baseball Facts, Finds, Flukes, and More! (New York: Random House, 2001).

McMillan, Robin. Official Major League Baseball 1995 All-Star Game Program (New York: Sports Publishing Group Inc., 1995).

Middlesworth, Hal. Detroit Tigers 1973 Press Radio TV Guide (Detroit: Tigers Baseball Club, 1973).

Middlesworth, Hal. Detroit Tigers 1974 Press Radio TV Guide (Detroit: Tigers Baseball Club, 1974).

Middlesworth, Hal. Detroit Tigers 1975 Press Radio TV Guide (Detroit: Tigers Baseball Club, 1975).

Middlesworth, Hal. Detroit Tigers 1971 Yearbook (Detroit: Tigers Baseball Club, 1971).

Middlesworth, Hal. Detroit Tigers 1974 Yearbook (Detroit: Tigers Baseball Club, 1974).

Paladino, Larry. Detroit Tigers 1987 Yearbook (Detroit: Tigers Baseball Club, 1987).

Russell, Cliff. Detroit Tigers 2004 Information Guide (Detroit: Tigers Media Relations Department, 2004).

Thorn, John, Phil Birnbaum, and Bill Deane. Total Baseball: The Ultimate Encyclopedia, 8th edition. (Toronto: Sport Classic Books, 2004).

Notes

1 Bruce Shlain, “Stormin’ Norman” in Oddballs: Baseball’s Greatest Pranksters, Flakes, Hot Dogs, and Hotheads (New York: Penguin Books, 1989), 134.

2 Shlain, 132.

3 Fred T. Smith, Tiger S.T.A.T.S., (Ann Arbor: Momentum Books Ltd., 1991), 39.

4 Bill Dow, “Former Tiger Norm Cash,” Baseball Digest, September 2001.

5 Correspondence with Sonny Eliot, April 2007.

6 Correspondence with Ernie Harwell, April 2007.

7 Dow.

8 Eliot.

9 Patrick Harrigan, Detroit Tigers Club and Community: 1945-1995 (Toronto: University Press, 1997), 103.

10 George Cantor, The Tigers of ’68: Baseball’s Last Real Champions (Dallas: Taylor Trade Publishing, 1997), 10.

11 Shlain, 137.

12 Cantor, 39.

13 Denny McLain and Dave Diles, Nobody’s Perfect (New York: The Dial Press, 1975), 72.

14 McLain/Diles, 72.

15 Denny McLain and Mike Nahrstept, Strikeout: The Story of Denny McLain (St. Louis: The Sporting News, 1988), 34.

16 McLaine/Diles, 72.

17 Correspondence with Jerry Casale, 21 May 2001.

18 Tim DeWalt, “Tribute: Norm Cash” in TigersCentral.com (2001-2005). Available from. http://www.tigerscentral.com/comments.php?id=239_0_1_0_C.

19 DeWalt.

20 Bill Shaikin, “California Strikes Gold in Ryan” in Nolan Ryan: The Authorized Pictorial History (Fort Worth: The Summit Group, 1991), 66.

21 Brian Britten, Detroit Tigers 2006 Information Guide (Detroit: Tigers Public Relations Department, 2006), 256.

22 “There Are So Many Norm Cash Stories…” in Detroit Tigers History (2005). Available from http://www.detroit-tigers-baseball-history.com/cash.html.

23 Chris Stern, Where Have They Gone?Baseball Stars! (New York: Grosset & Dunlap, 1979), 137-138.

24 Stern, 138.

25 DeWalt.

26 Stern, 138.

27 Cantor, 215.

28 DeWalt.

29 Harrigan, 103.

30 Schlain, 145.

31 Cantor, 215.

32 Shlain, 145.

33 Ernie Harwell, Life After Baseball (Detroit: The Free Press, 2004), 137.

34 Shlain, 139.

35 Shlain, 139-140.

36 Tom Stanton, The Final Season: Fathers, Sons, and One Last Season in a Classic American Ballpark (New York: St. Martin’s Press, 2001), 236.

Full Name

Norman Dalton Cash

Born

November 10, 1934 at Justiceburg, TX (USA)

Died

October 12, 1986 at Beaver Island, MI (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.