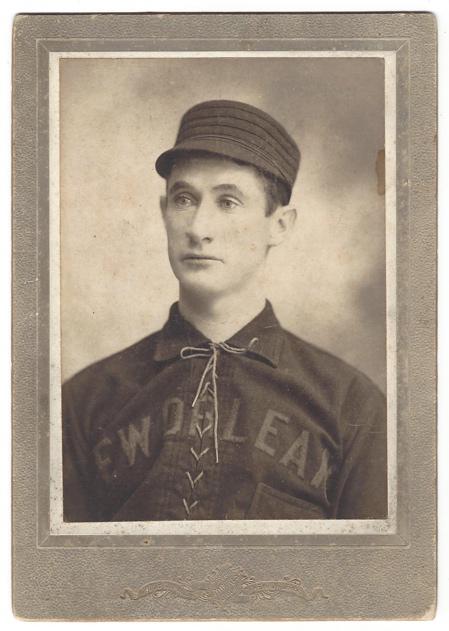

Abner Powell

Baseball fans attending games today are still experiencing features of the sport that were introduced by Charles Abner Powell, a baseball pioneer of the late 19th century.1 In June 1950 Connie Mack sent a 90th birthday message to Powell, adding “You, Abner, have contributed more to the game of baseball than any other man alive today.”2 Today Powell – a player, manager, team owner, innovator, and colorful personality – is often overlooked, if not completely forgotten.

Powell was born on December 15, 1860, to Mary Lewis Powell, and Thomas Powell posthumously, in Shenandoah, Pennsylvania. His parents were born in Wales and married about 1845 before immigrating to the U.S. in 1850. They settled in the northeastern part of Pennsylvania, known as the Coal Region.

Powell had five older siblings. A grandson of Abner’s, Hoyt Powell, described to the author: “School wasn’t emphasized much back then, and [Abner] left after about the fourth grade. His mom had to take in boarders for money.”3 Abner helped by working in the coal mines. Hoyt explained, “Abner had to open the doors for the mules pulling carts loaded with coal to come out of the mines. Once, the boss beat Abner for falling asleep and allowing the carts to back up!”4 Coal miners were being paid an average of $2.07 per day.5 At 15 he went to work for the Shenandoah Herald as a “printer’s devil” – a young apprentice.

Powell wanted to make it in the rough unruly sport of “base ball.” He batted left-handed and was a swift base runner and outfielder. Listed as 5-feet-7 or 5-feet-8 and weighing 160, he could hit for average and steal bases. He was recruited to play on a semipro traveling team out of Philadelphia, making fifty cents a day.6

By April 1883, the 22-year-old had earned a tryout in the National League: “Abner Powell, the Shenandoah printer, is proving a valuable acquisition on the Providence team. Manager Harry Wright hopes to have a team in Powell and Chris Fulmer. He designates them the ‘Schuylkill Battery’.” 7

Interviewed in 1935, Powell remembered, “I was not a pitcher, but one day I was tossing a few to Fulmer, just to limber my arm up, when Wright walked over and said, ‘Listen young fellow, from now on you’re going to pitch for my club.’” 8 He was effective pitching several complete games in spring training, but he and Fulmer were left off the League team. Powell and fellow Coal Region player Fulmer continued to play together for several teams until 1887.

In 1884 they signed with the Union Association Washington Nationals, managed by Mike Scanlon. They made their major league debuts on August 4 as battery mates. Powell commented on the times of the UA during an interview in 1941: “The Union Association gave the National League players extra money to jump their contracts. The loop folded after one season, but it gave the National fits.”9

Powell’s next stop was Baltimore; released in July 1886, he signed with Cincinnati of the American Association amid glowing reports: “The Cincinnati nine are highly elated at Powell’s accession to their number. In no game he has pitched has the Baltimore club given him support, nor has he at any time been hit hard….is a splendid outfielder, as good as Mullane . . . and as good a baserunner as the Cincinnatis have.”10

An adventure in the outfield while playing for Cincinnati in 1886 against Louisville has etched Abner Powell’s name in the annals of “This Date in Baseball History”. On August 22, with the score tied, 3-3, in the top of the 11th inning, Louisville Colonels’ batter William “Chicken” Wolf stroked a drive to deep center field, and Powell gave chase. A small dog that was in the outfield came over and reached Powell, bit into his uniform leg and wouldn’t let go, while Wolf ran all the way home for what became the winning run! 11 Undoubtedly Powell is the first and only victim in major league history of an inside-the-“bark” game-winning home run. The novelty value of this incident can be partially explained by its occurrence during the dog days of August.

Powell had chronic trouble with his forefinger while pitching, earning the nickname “Me Pitchin’ Finger”. Whatever circumstances, ailments, nagging injuries, or canine calamities that befell him in 1886 were already just a distant memory by the end of the year.

New Orleans was granted a franchise in the two-year-old Southern League in 1887. The city’s population increased from 168,000 in 1860 to 242,000 in 1890. During the 1800s “the city was the most popular one in the South for the professionals to tour during the winter and early spring.”12 Renovations took place at The Sportsman’s Park, increasing capacity to a little over 5,000 as enthusiasm accelerated for the brand-new home team. Owner Toby Hart and his staff began signing players in December of 1886. Contracts totaled $1,740 per month for 14 players, which made New Orleans “about the cheapest team in the league.”13

Powell and other players, including Harry Eldred, Joe Dowie and Ed Cartwright, were inked to contracts. In a Sunday newspaper feature entitled “A Promising Baseballist,” a writer introduced Powell as “the highest salaried player in our club, and perhaps in the Southern League. He will, in all probability, be the captain of the club.”14 Powell’s salary was $175 or $180 a month depending on the source.15

Abner was often described as a non-drinker and non-smoker, a person who “is seldom seen in barrooms of hotels”16 while on the road. Hoyt Powell declared that, as far as he knew, “he never smoked or drank.”17 These character traits paid real dividends for Powell- being wise with his money reaped future rewards.

In an interview Powell reminisced: “I came to New Orleans for excitement, and I got more than I bargained for that first year. I doubt if anyone in the game ever put in as active a year as that one was for me.”18 The season opener against the Mobile Swamp Angels on Sunday, April 17, was won by the home team, 5-2, before 4,700 paid onlookers. The newspaper account of the game reported that Powell “ran the bases with daring” and played well in the outfield.19

The Southern League was handicapped when Atlanta didn’t rejoin for 1887, and the remaining six cities of the league were strung out and “had entirely too much mileage to contend with, even with the liberality of the railroads in passenger fares.”20 The league stumbled to the finish, the Pelicans finishing first with a 78 — 37 record. Powell came into his pitching prime with 20 wins, including the first one-hitter in Pelicans history, while batting .335 with 92 stolen bases.

Powell saw the potential the Pelicans had in this large city; at 26, he was invited by Hart to take part in the business end of the team.

Biographical sketches of Abner Powell often credit him with introducing the “first” Ladies Day in baseball. But other organizations offered free admission to certain games for ladies when accompanied by a man. In 1887 Powell persuaded Hart to promote a regular Ladies Day: “Well, I had had time to see that New Orleans was a pretty wide-open town. Its citizens didn’t go too much by convention as the folks up East did. For instance, Sunday baseball was not allowed up there, but it was the biggest crowd day of the week in New Orleans. Hart wanted that first year to be a big one, but at first attendance was not much to brag on. I thought the girls would like the game if we could just get them out to the park, but society didn’t approve of them attending sporting events. We talked the subject over, and then suggested that we let all the ladies in free and call it ‘Ladies Day’. And if they came, we would let them have a regular day of free admittance every week. Hart said, ‘Come on Powell, we’re going to the newspaper office and advertise your idea!’” 21

Despite many critics of this proposal, the first Ladies Day, on Thursday, April 28, 1887, was a success. A local paper reported on the event:

“It was a bright and joyous afternoon out at Sportsman’s Park … The scenes of ruffianism, boisterous talk and even sky-larking on the field have been entirely stopped, and the most thorough order prevails. There were any number of sets and bevy of beautiful young girls in their spring costumes, handsome matrons with their lovely daughters, pretty girls with their beaux, and all were highly delighted with the evening’s sport.”22

The promotion caught on and eventually became a regular event throughout all of baseball for decades.

The promotion caught on and eventually became a regular event throughout all of baseball for decades.

Canvas tarpaulins had been widely used for years to protect merchandise on ships. The tarps were used on the river docks of New Orleans to cover cotton bales and other goods. Since the spring rains interfered with games, Powell applied this idea to baseball. The St. Louis club in 1884 had reportedly used coverings on the bases and base paths during wet weather.23 Powell’s large canvases covered the entire infield and were treated with a wax-like substance to make them waterproof.24 This innovation eventually spread to major league parks.

In first place late in September, the Pelicans played the second-place Charleston Seagulls in South Carolina. Even though Powell received a “silver-plated epergne filled with flowers and a button-hole bouquet for each of the players,” the local paper reported that “he was very mad at the way the game was going against him, and as usual on such occasions, vented his spleen by cursing the umpire [Simonin]”.25 The paper reported what happened at the Waverly hotel that evening:

“Two of the players were just finishing supper when Powell came down into the corridor of the hotel. Simonin stepped up and said he wanted Powell to come with him. Powell turned and saw three men with Simonin. Just then he received a blow on the side of the head which felled him. He got up and Simonin struck him full in the face, and again Powell was felled. The players present then rushed to his rescue, but the men with Simonin drew knives and stopped them. Chivalrous Charlestonians stepped in, and Powell was lifted up and taken to his room.”26

Powell later wired Hart requesting advice on playing the rest of the series, and when security for the players couldn’t be guaranteed, Hart sent word to return home. When they arrived in New Orleans about 7:00 a.m. the following day, they were met by “nearly a thousand people at the depot. There were carriages in place for the players, and several private carriages followed. Faranta’s Band led off, and the procession moved along Canal, Camp, and St. Charles streets. A substantial breakfast ensued, and the team was toasted as the coming champions.”27

In November Powell was put in charge of signing players for 1888. In addition to continuing as captain he would now be the manager of the team, handling the finances and having a stake in the club. Top players for the team in 1888 were John Sneed and Perry Werden. The league struggled to stay afloat but gradually disbanded. In July the third-place Pelicans left to play in the Texas League, which was also shedding teams and faltering. Powell pitched, managed, and led the Pelicans to an 18-9 record despite playing all of their games on the road.

In 1889 the Southern League tried again. New Orleans led the pack early and didn’t look back. The five other teams struggled, switched cities, and/or disbanded early. The champion Pelicans dominated with a 46-9 record behind the batting of Mark Polhemus, Thomas McGuirk and Powell, but fan interest ebbed around the league, disorganization ruled, teams’ finances dropped, and the league folded again.

Before the season was cut short, Powell started a “Knothole Club” to allow kids to attend games free once a week. This became another successful promotion for baseball; the St. Louis Cardinals Knothole Gang allowed a reported 65,000 free admissions for kids in 1920.28

Powell finished the season with Hamilton, Ontario, of the International Association, where he managed, pitched, and batted .322. In 1890 he signed with Spokane Falls, then spent two years in Seattle as player-manager and handling the finances in Seattle. Before the 1892 season ended, Abner took an offer from New Orleans to manage again in the reorganized Southern League, and apparently restore some needed order to the team. Word went out to the players before he arrived that there would be no more beer. The Powell-led Pelicans were strong in a down-to-the-wire finish but tied for second. Powell’s team leadership skills were again confirmed.

Charles Genslinger and Henry Powers, who took over control of the Pelicans in 1891, put Powell in charge of signing players for 1893 and gave him the title of vice president in addition to his playing and managing, a responsibility that Powers relieved him of in 1894.29 In February 1895 Abner married Bertha Wasley of Shenandoah. The Powells moved to New Orleans and over the next nine years had three children: Roy, Mae, and Wasley.

Powell was reinstated as player-manager for 1895 and guided the Pelicans to a fourth-place finish. The following year they won the pennant; now 35, Powell hit .318, stole 60 bases, and led the league in runs scored. He was praised for his team “generalship” and wise control of his employer’s funds. In 1897 yellow fever, long a threat in Louisiana, hit New Orleans with 298 deaths.30 Teams were reluctant to play there. The league cancelled the season.

The Pelicans began play at their new Athletic Park in 1898, but the league folded on July 4. Before the end of the season, Abner Powell introduced another historic innovation to baseball: the detachable rain check ticket stub. The usual method for satisfying fans when a game was cut short by rain was for them to line up and receive square “pasteboard” tickets for the next game instead of a cash refund. Powell noticed that more pasteboard tickets were being handed out than tickets had been sold for the game. Fence-jumpers and others who were friends of park employees or politicians were attending free as it was, and they also got in line for the tickets. This was a widespread money-losing problem throughout baseball.

Seeking a solution to this dilemma, Powell visited C. A. Lick, a partner in the Weldon, Williams & Lick printing company in Fort Smith, Arkansas, and suggested a smaller paid admission ticket with a detachable dated stub that could be retained and used to exchange for a ticket to a future game. (Biographical sketches of Powell indicate dates of 1887, 1888, 1898 or 1899 for the introduction of the rain check.) The author reached out to WW&L in February 2019 and spoke with Executive Chairman Jim Walcott, who happens to be a great grandson of C.A. Lick. He stated that regarding this topic, his company’s story is “The Pelicans had a problem with rainouts and together we solved that Rain Out Problem with the ‘rain check’ stub.”31 Thus was born the rain check. Interviewers of Powell over the years would mention that Powell could have patented the idea, but Powell explained, “Well, I don’t have any regrets about that. What we did, we did for the game; personal gain was incidental. I know that kind of reasoning is hard to understand now.”32

Powell’s innovation was praised in the spring of 1903: “One of the greatest schemes that has ever been hit upon for the convenience of the patrons of the games and for the manager as well is the ticket and rain check scheme originated by Manager Powell.” (Powell was in charge of Atlanta in 1903.) The report went on: “Manager Powell has made an innovation in making it five innings instead of three as the rain limit.”33 Only a few other teams picked up on the idea at first, including the Brooklyn Superbas in August 1905.34

The 1899 season was Powell’s last as a player. The following year he was in the national news with plans to organize a baseball trip to Cuba in January. He took with him major league players Harry Steinfeldt, Pearce Chiles, and Sport McAllister, plus many minor league stars. Powell was now being referred to as a “magnate” on the order of Pop Anson. Cincinnati business manager Frank Bancroft remarked, “I’ll bet he has a cinch with the players he took with him. Powell will pay their passage and their board and keep for himself the lion’s share of their part of the receipts. I wouldn’t be surprised if Abner Powell cleared a couple thousand dollars out of the Cuban trip.”35

Almost immediately upon his return to New Orleans, he was interviewed regarding the prospects for a new league. Powell attended a meeting in Birmingham at the end of January and said, “I was appointed on a committee to visit cities and talk up baseball, or rather assist in organizing clubs.”36 At an October 1900 meeting in Memphis, Powell was able to collaborate with Charlie Frank, Newt Fischer and other representatives of southern cities, to form the new Southern Association for 1901.

A story often told recounts that Powell traveled to North Carolina during the 1901 season and signed a whole new team of 12 players to replace his underperforming Pelicans. The New Orleans roster does list seven players with playing time in the Virginia-North Carolina League that season, but there is a lack of evidence showing that there was a sudden complete overhaul. The Pelicans were in last place on July 13. The players he recruited helped New Orleans finish strong that season with a winning record.

Abner Powell’s ownership role was key to the success of the SA in the beginning. He said in a 1950 interview, at the age of 89, “In the old days towns weren’t big enough for baseball. You’d make the grade for a couple of years, then be forced to let up for a while. My job was to always re-organize.”37 Powell’s dedication was steadfast. In order to help keep the league going, he invested in multiple teams in 1901-02 in addition to his controlling interest in the Pelicans. Powell and co-owner E. T. Peter of the Selma, Alabama, team, moved to Atlanta for 1902.

Owner-manager Powell’s Pelicans drew 98,000 in 1902, which led the league. “Uncle Abner,” as he was now called in the press, and his boys finished 72-47 in third place, 7 1/2 games behind the Volunteers. In December Powell bought out his Atlanta partner, making his total investment in that club about $4,000. Under Powell’s promotional skills Atlanta, now called the Crackers, drew 84,000 in 1903. The Crackers were 59-59 in 1903, then zoomed to 78-57 in 1904, finishing second and drawing 135,000.38

When Powell made a profit of $6,000 in 1903, it caught the attention of the locals. They did not appreciate the money going to an outsider and officials took action, proposing “a fifty-dollar license fee plus a 5 percent tax on gross receipts.” The Atlanta Journal reported: “There is no case on record where a team in any league or town is taxed outside of the license.” The council ended up “setting a two-hundred-dollar license fee plus one hundred dollars for police protection. Fulton County added its own three-hundred-dollar assessment.”39 There was also the issue of the ballpark. Piedmont Park was purchased by the city and Powell envisioned lease problems. In 1905 Powell agreed to sell for an amount between $17,000 and $20,000, depending on which source is cited.40 The higher figure is equivalent to over $570,000 in 2019.

While running the Atlanta team in 1902 Powell was instrumental in convincing a young sportswriter, Grantland Rice, to leave Nashville and work at the Atlanta Journal. Rice never forgot how Powell supported him when he started out and regarded him as a great friend for life. Powell’s time in his chosen profession of baseball ended in 1905 when he sold his stakes in the Atlanta and Nashville clubs. Charlie Frank purchased Powell’s shares in the Pelicans in 1904 and took over as the manager.

Powell’s third child, Wasley, was born in December 1905 in New Orleans, and perhaps family priorities were a factor in Powell’s decision to leave baseball. During his 22-year major and minor league career, Abner Powell played in over 1,000 games and was part of several pennant-winners as a player and player-manager. He developed and sent dozens of players to the majors, owned and operated franchises in several leagues, and gave the national game landmark innovations. Powell was regarded as equal in stature to other great figures of the game such as Connie Mack and Clark Griffith, with whom he associated early in his career.

After baseball, Powell still maintained his entrepreneurial spirit, and became known as a prominent “automobilist” in New Orleans with a Morgan Steamer dealership. Interviews with family members revealed that Abner operated various businesses and managed City Park’s first miniature golf course. During the tough times of the Depression, Powell took members of his extended family into his home on Canal Street and supported them. His wife Bertie passed away in 1937, not long after retiring as principal of Beauregard school for many years.

Powell enjoyed his stature as the “Father of New Orleans Baseball.” Very often it was written that he took great care of himself, and he was eager to show off his ability to pitch, hit, bunt and run the bases at baseball get-togethers long after retirement age for most. In 1946 the Pelicans staged Abner Powell Night at Pelican Stadium. It was reported that “Powell donned a uniform and displayed much pep in throwing the ball from the pitcher’s box to home plate.”41 He was 85.

At the age of 92, Powell was trimming a tree in his yard when he reportedly suffered a heart attack. While hospitalized, he suffered a second attack and died on August 7, 1953. He was widely regarded as the oldest living former major leaguer, but records show that Tom J. Lynch, born in April 1860, was older by eight months. At the time of Powell’s death in 1953, Grantland Rice cited his many accomplishments and wrote that “Abner Powell has done more for baseball than anyone can know.”42

Abner Powell was inducted into the Diamond Club of Greater New Orleans Hall of Fame in 1966, the Greater New Orleans Sports Hall of Fame in 1972, the New Orleans Professional Baseball Hall of Fame in 2006 and the Jerry Wolman North Anthracite Chapter of the Pennsylvania Sports Hall of Fame in 2019. As Grantland Rice put it, “Up to the day of his death he was deeply interested in everything that took place in his favorite business and pastime – the National Game. He belonged to baseball.”43

Acknowledgments

The author would like to give special thanks to two of Abner Powell’s great-grandchildren, Jere Powell Mitternight and Roy R. Powell for their time given in sharing history of the Powell family. Thank you to my father Eugene J. (Jack) Gomes Jr. for sharing memories of his grandfather, Abner Powell.

This biography, originally published in December 2019 and updated in November 2025, was reviewed by Warren Corbett and Norman Macht and fact-checked by Chris Rainey.

Sources

Books, book chapters, book section

- Achorn, Edward. Fifty-nine in ’84: Old Hoss Radbourn, Barehanded Baseball & The Greatest Season A Pitcher Ever Had (HarperCollins, 2010), chapter 3.

- Armour, Mark, ed. Rain Check: Baseball in the Pacific Northwest (Society of American Baseball Research, University of Nebraska Press, 2006), 5-10.

- Gisclair, S. Derby. Early Baseball in New Orleans: a history of 19th century play (McFarland & Company, Inc., 2019).

- Light, Jonathan Fraser. The Cultural Encyclopedia of Baseball, second ed. (McFarland & Company, Inc., 2005), 401, 402, 405, 518, 605, 720.

- Morris, Peter. A Game of Inches: The Game behind the Scenes (Chicago: Ivan R. Dee, 2006), 61.

- Nemec, David. The Great Encyclopedia of Nineteenth Century Major League Baseball, second edition (University of Alabama Press, 2006), 455, 457, 458.

- Nemec, David and Zeman, Dave. The Baseball Rookies Encyclopedia (Brassey’s, Inc., 2004), 27.

- Reiss, Steven A. Touching Base: professional baseball and American culture in the progressive era (Revised edition, University of Illinois Press, 1999), 57-58.

- Somers, Dale. The Rise of Sports in New Orleans 1850-1900 (Baton Rouge Press, 1972), chapter 6.

Newspapers or Magazines

- Englert, Joe. “Abner Powell Sage of Pel Baseball,” New Orleans Item, June 21, 1950, 27.

- Flanagan, Val J. “Abner Powell, a Star in the ‘80s, Would Take Game Off Bench and Put It Back on the Field,” The Sporting News, February 2, 1933, 7.

- Flanagan, Val J. “Rain-Check Evolved in 1889 to Check Flood of Fence-Climbers, Says Originator, Now 83,” The Sporting News, April 8, 1943, 2.

- Hoag, Edwin. “Baseball’s Great Innovator,” Sports Illustrated, March 19, 1973, 114-116.

- McClelland, Marshall K. “The Abner Powell Story,” New Orleans Item, August 22-28, 1953.

- McClelland, Marshall K. “Baseball’s Pioneer,” Stars and Stripes Pacific, July 21, 1955, 16-17.

- Price, Jim. “Spokane Indians-100 Years,” The Spokesman-Review, June 21, 2003.

- Price, Jim. “Spokane’s first pro team also its first champ” The Spokesman-Review, May 17, 2015.

- Rice, Grantland. “Powell Deserves Hall of Fame Spot,” New Orleans Item, August 22, 1953.

- Witt, William. “Ab Powell, ‘Forgotten Man of Baseball’ Deserves Recognition,” Evening Herald, Shenandoah PA, March 27, 1954, 2.

- “Pel Fans Honor Old-Time N.O. Pilot, Abner Powell,” The Sporting News, July 17, 1946, 28.

- “The Schuylkill Battery,” Harrisburg Daily Independent (PA) April 28, 1883, 1.

- Ashbury Park Press (NJ)

- Atlanta Constitution

- Chicago Tribune

- Cincinnati Enquirer (OH)

- Daily Picayune-New Orleans

- Evening Herald, Shenandoah (PA)

- Evening Star (Wash. D.C.)

- Evening World (New York, NY)

- Hazleton Plain Speaker (PA)

- Herald Dispatch (Decatur, Illinois)

- Lancaster Daily Intelligencer (PA)

- Louisville Courier-Journal (KY)

- National Republican (Wash. D.C.)

- New Orleans Item

- New Orleans States

- New York Times

- Pensacola Journal (FL)

- Pittsburgh Daily Post (PA)

- Pottsville Republican (PA)

- Providence Evening Press (RI)

- Seattle Post-Intelligencer (WA)

- Spokane Falls Daily Chronicle (WA)

- Sporting Life

- The Sporting News

- Louis Post-Dispatch (MO)

- Times-Democrat (New Orleans)

- Times Picayune (New Orleans)

- Wilkes-Barre Record (PA)

- Wilkes-Barre Times-Leader (PA)

Online

- Derr, Ed. “Delirious Summer of 1882,” Schuylkill County Baseball History, https://schulkillbaseball.files.wordpress.com/2015/09/11dbf-1882reds.jpg, accessed October 2018.

- “Coal Region,” https://www.wikipedia.com, accessed October 2018.

- “Storyville, New Orleans Red-Light District 1897-1917,” https://www.storyvilledistrictnola.com/history.html.

- History of Wages in the United States from Colonial Times to 1928, Revision of Bulletin No. 499 with United States, Bureau of Labor Statistics Washington D.C. (U.S.G.P.O., 1934) (https:/HathiTrust.org, 331), accessed October 2018.

- Last living players from teams with no living representatives, https://www.baseball-reference.com, accessed August 10, 2019.

- WW&L.com/resources/About WW&L (Weldon, Williams & Lick printing co.), accessed February 13, 2019.

- “Yellow Fever Deaths in New Orleans, 1817-1905,” nutrias.org/facts/feverdeaths.htm (New Orleans Public Library), accessed May 15, 2019.

- “$1,000 in 1905-2019 Inflation Calculator.” U.S. Official Inflation Data, Alioth Finance, August 15, 2019, https://www.officialdata.org.us/inflation/1905?amount=1000.

- https://www.ancestry.com

- https://www.baseball-reference.com.

- http://wwwdavemanuel.com/inflation-calculator.php?theyear=1905&amountmoney=20000, accessed January 22, 2019.

- https://www.newspapers.com

- https://www.threadsofourgame.com

Archives / Other materials

- Baseball Hall of Fame Library, player file for Abner Powell, accessed July 1996.

- United States Department of Commerce, Bureau of the Census, 1860, 1880, 1890 and 1900.

Personal Correspondence

- Gisclair, S. Derby, email correspondence with author, June 3, 2004.

- Gisclair, S. Derby, phone conversation with author, February 9, 2019.

- Gisclair, S. Derby, face-to-face interview, April 17, 2019.

- Gomes, Eugene J. Jr., face-to-face conversations with author, June 20, 2015 and September 4, 2015.

- Mitternight, Jere, email correspondence with author, April 4,5 and 7, 2015.

- Mitternight, Jere, face-to-face interview with author, October 11, 2018.

- Powell, E. Reid, phone conversation with author, March 1992.

- Powell, Hoyt, phone conversations with author, March 20, 2004 and November 18, 2004.

- Powell, Roy R., face-to-face interview with author, October 11, 2018.

- Price, Jim, email correspondence with author, March 29, 2012.

- Schott, Arthur O., face-to-face interview at his home, March 1992.

- Schott, Arthur O., written letter given to author, April 1, 1992.

- Walcott, Jim, phone conversation with author, February 13, 2019.

- Walcott, Jim, email correspondence with author, February 13, 2019

Notes

1 Schuylkill County Archives, 1895 Marriage License Docket Book 7, A139. This source lists Powell’s name as Charles A. Powell. It was required that both parties be present for the marriage license application and provide their legal names. Sources such as baseball-reference.com and retrosheet.com have it as Abner Charles Powell. His gravesite portrays the name as Abner C. Powell. Other sources such as Major League Baseball Profiles, 1871-1900, Vol. 2 (2011) by David Nemec and The Baseball Encyclopedia have it as Charles Abner Powell.

2 Englert, Joe. “Abner Powell Sage of Pel Baseball,” New Orleans Item, June 21, 1950, 27.

3 Hoyt Powell, phone conversation with author, March 20, 2004.

4 Powell.

5 History of Wages in the United States from Colonial Times to 1928, Revision of Bulletin No. 499 with United States, Bureau of Labor Statistics Washington D.C. (U.S.G.P.O., 1934), https://HathiTrust.org, 331. accessed October 2018

6 Gisclair, S. Derby. Early Baseball in New Orleans: a history of 19th century play (McFarland & Company, Inc., 2019), 142.

7 Gisclair.

8 New Orleans Item, March 9, 1935, 6.

9 Ashbury Park Press, May 18, 1941, 8.

10 The Sporting News, August 2, 1886, 5.

11 “It’s Sixtieth Victory: The Louisville Club Defeats the Cincinnatis in a Great Eleven-Inning Contest,” Courier-Journal (Louisville, KY), August 23, 1886, 2.

12 Gisclair, S. Derby. Early Baseball in New Orleans, 127.

13 Gisclair 131.

14 “A Promising Base Ballist,” Times-Democrat, February 6, 1887, 7.

15 Hoag, Edwin. “Baseball’s Great Innovator,” Sports Illustrated, March 19, 1973, 114 and

McClelland, Marshall K. “Baseball’s Pioneer,” Stars and Stripes Pacific, July 21, 1955, 16-17.

16 Daily Picayune-New Orleans, October 2, 1887, 3.

17 Hoyt Powell, phone conversation with author, March 20, 2004.

18 McClelland, Marshall K. “The Abner Powell Story,” New Orleans Item, August 25, 1953, 17.

19 Daily Picayune-New Orleans, April 18, 1887, 2.

20 The Sporting News, February 8, 1934, 8.

21 McClelland, Marshall K. “The Abner Powell Story,” New Orleans Item, August 25, 1953, 17.

22 Times-Democrat, April 29, 1887, 2.

23 Morris, Peter. A Game of Inches: The Game behind the Scenes (Chicago: Ivan R. Dee, 2006), 61.

24 Gisclair, S. Derby, face-to-face interview, April 17, 2019.

25 Daily Picayune, September 30, 1887, 3.

26 Picayune, October 2, 1887, 3.

27 Picayune.

28 Light, Jonathan Fraser. The Cultural Encyclopedia of Baseball, second ed. (McFarland & Company, Inc., 2005), 518.

29 Gisclair, S. Derby. Early Baseball in New Orleans, 187.

30 “Yellow Fever Deaths in New Orleans, 1817-1905,” nutrias.org/facts/feverdeaths.htm (New Orleans Public Library) accessed May 15, 2019.

31 Walcott, Jim, email correspondence and phone conversation with author, February 13, 2019.

32 McClelland, Marshall K. “Baseball’s Pioneer,” Stars and Stripes Pacific, July 21, 1955, 16-17.

33 Atlanta Constitution, March 8, 1903, 2.

34 Times Union (Brooklyn), August 16, 1905, 7

35Wilkes-Barre Record, January 13, 1900, 15.

36 Times-Democrat, January 31, 1900, 8.

37 Englert, Joe. “Abner Powell Sage of Pel Baseball,” New Orleans Item, June 21, 1950, 27.

38 Reiss, Steven A. Touching Base: professional baseball and American culture in the progressive era (Revised edition, University of Illinois Press, 1999), 57-58.

39 Reiss, Steven A. Touching Base, 57-58.

40 Reiss, and Hoag, Edwin. “Baseball’s Great Innovator,” 114-116.

41 “Pel Fans Honor Old-Time N.O. Pilot, Abner Powell,” The Sporting News, July 17, 1946, 28.

42 Rice, Grantland. “Powell Deserves Hall of Fame Spot,” New Orleans Item, August 23, 1953, 11.

43 Rice.

Full Name

Charles Abner Powell

Born

December 15, 1860 at Shenandoah, PA (USA)

Died

August 7, 1953 at New Orleans, LA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.