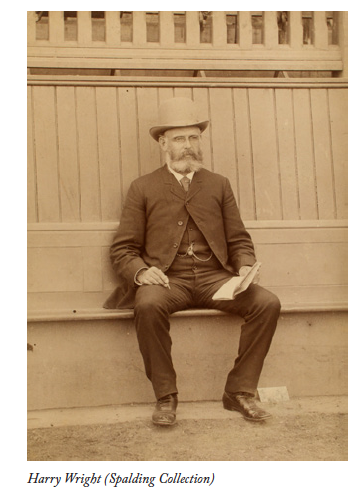

Harry Wright

William Henry Wright, better known to the baseball community as “Harry” Wright, today strikes historians as, in the words of Bruce Markusen, an “especially underrated Hall of Famer.”1 Popularly regarded in his time as “The Father of Professional Baseball,” Wright’s modern legacy pales in comparison, though many of his innovations characterize the game that we know today.

William Henry Wright, better known to the baseball community as “Harry” Wright, today strikes historians as, in the words of Bruce Markusen, an “especially underrated Hall of Famer.”1 Popularly regarded in his time as “The Father of Professional Baseball,” Wright’s modern legacy pales in comparison, though many of his innovations characterize the game that we know today.

The time and place of Wright’s birth to Samuel Sr., and Annie Tone Wright (married in 1830) are not certain, but records indicate that the event occurred on January 10, 1835, in Sheffield, Yorkshire, England. Mormon records suggest the date of November 8, 1832, in Leeds, England, and his death certificate lists an age that would place his birth at December 13, 1834.2 But due to supportive census records and the simple fact that Wright failed to contradict the 1835 date during his lifetime, one may presume that it is correct.

Further mysteries surround Wright’s early life. The exact date of his emigration to America — New York City, specifically — is also uncertain, though it appears that his father brought his family to the New World in 1836 on the promise of a spot on the St. George’s Dragonslayers cricket team. During that year, Wright witnessed the birth of his brother Dan, seemingly unknown to baseball historians because he was the only one of the four Wright sons not to take up the game professionally. He subsequently moved to San Jose, California, sometime between 1861 and 1877.3 Dan was joined in the family by brothers George (b. January 26, 1847) and Samuel Jr., or “Sammy” (b. November 25, 1848), and, finally, sister Mary (b. 1858).

Rumors today flourish that George was in fact merely a Hall of Fame half-brother of Harry Wright. This, in fact, is a myth created by the misstatement of George’s housekeeper on his 1937 death certificate that he was the son of a woman named Mary Love. The existence of Love cannot be confirmed or denied, but she is certainly not the mother of George Wright.

Harry Wright dropped out of public school at the age of 14, in 1849, to apprentice as a jeweler at Tiffany’s and the next year join the Dragonslayers, on which his father was the star and idol of cricket circles and would continue to play for the team until 1869. By 1857, Harry began receiving money for his performance, but while coaching George in cricket on the Elysian Fields in Hoboken, New Jersey, the next year, he looked over to an adjoining field and witnessed his first game of baseball.

Wright quickly adapted to, and grew to love, the sport. At a rather tall 5′ 9 3/4″ and 157 pounds, the right-hander became a formidable athlete. He and his brother, George, were regarded by the New York Dispatch as “the best exponents of batting as a science in the country”, and Harry personally as “the finest, safest, best, and least showy player in America” according to the Detroit Post.4

That year he joined the New York Knickerbockers and participated in the heralded Fashion Course Matches that first charged money for admittance. In 1863 he became the first player to (openly) receive money for a game when a “benefit” was held by the Knickerbockers for him, his father, and others. Harry, the only one to actually make money from the benefit, received $29.65.

The Civil War so decimated the Knickerbockers’ schedule that Wright decided to join the New York Gothams in 1864. But by the next year he had tired of baseball and decided to start over as a cricketer in Cincinnati, Ohio.

He went west with his wife of four years, Mary Fraser, and their children, four-year-old Charles, young Lucy Louise, and newborn George William, or “Willy.” At some point between this move on March 8, 1865, and Wright’s remarriage to Caroline Mulford on September 10, 1868, Mary died, though the details are not known. With Carrie he was to have seven children: Hattie (b. March 30, 1869), Stella (b. 1870), Harry II (b. August 4, 1871), Carrie (b. January 27, 1874), Albert (b. December 20, 1874), and William (b. July 13, 1876). The two sets of children resented each other, and the Fraser/Wright children later lived with Harry’s brother, Sammy, as well as with his sister Mary.

While in Cincinnati, Wright quickly reverted to baseball in much the same fashion that he first came to it, by witnessing a game on an adjoining field as he played cricket. After talking with Cincinnati Base Ball Club (CBBC) president Aaron Champion, he started a mass exodus of Union Cricket Club players to the CBBC that took the field together on September 26, 1866. He adapted his bowling techniques from cricket to become an effective pitcher known for his off-speed pitches that differed from most of the hard-throwing pitchers of the day. He would later use this to relieve fireballer Asa Brainard effectively and thus institute the strategy of relief pitching.

The competitive fire of Wright and his fellow club members was sparked by the western visit of the dominant Washington Nationals, for whom his brother, George, played shortstop, and the burgeoning ambition for their own tour. Part of this was due to the fact that the Red Stockings, as the team came to be called, were clearly the dominant club in the west and thus competition was not conducive to profits. Only a traveling, excellent team would be able to accomplish that.

It was decided that the Red Stockings would field an openly all-professional team in 1869, the first of its kind. Originally the team officials intended to sign every player that won an 1868 Clipper Medal, the equivalent, one may say, of a modern All-Star selection, but when that proved unrealistic, Wright was designated as scout and general manager. He selected a team of young players that, even if not individually outstanding, would function well as a team. His emphasis on teamwork later earned him recognition by sportswriter Tim Murnane as the originator of the very concept itself.5 He earned this distinction by the invention and application of such methods as hand signals to all players in the field, calling balls in the air, having one fielder back up another, platooning, and the hit-and-run.

The success of Wright’s management was apparent. The Red Stockings dominated at home and abroad throughout the 1869 season. Throughout a tour of the East against the heralded teams of New York, Philadelphia, and elsewhere, the club went undefeated, shocking the sports world. The fame of the Red Stockings became so great that they were asked to take a tour of the western United States as well, specifically California. No such trip had ever been undertaken. But the Cincinnatis swept the competition, enhancing the popularity of baseball in the process.

While most would regard the success of the Red Stockings as being strictly contained in their win total, in fact they scored just as precious a victory in the conduct of their behavior. As the first salaried club, the Cincinnatis precipitated great controversy over the institution of professionalism. Any mingling of money with the game at that point was regarded as a recipe for corruption and the attraction of carousing undesirables, which would spell doom for the game. However, the Red Stockings were perhaps the most disciplined team ever to attract such attention, as demanded by manager, center fielder, and executive Harry Wright.

Wright’s reputation as the most ethical gentleman in the game – “There was no figure more creditable to the game than dear old Harry,” said The Sporting News 6 – defied the money-grubbing stereotype of what an exponent of professionalism was supposed to be. Instead, he emphasized the necessity of fair play and high ethical standards for the advancement of the game, an admonition that he heeded as well. In one 1868 home game, he reversed the blatantly errant ruling of an umpire seeking to curry the favor of the Cincinnati crowd. Owing largely to this action, the Red Stockings went on to lose the game. In later years Wright himself was entrusted to umpire games within his own league.

The Red Stockings eventually met defeat in a close and controversial game against the Brooklyn Atlantics on June 14, 1870. From there, the club unraveled after losses to other clubs and the desertion of the Cincinnati fan base. The once-adoring press turned sharply on the club, which by the end of the year officially splintered in an ugly public drama.

Wright took the team name and several of its players to Boston in the new National Association (NA), the first professional baseball league. By the end of its run in 1875, it came to be known as “Harry Wright’s League” due to his club’s domination of the circuit. After a disappointing 1871 season, finishing second to Philadelphia in the new league, the club rebounded to capture four consecutive titles, a feat unequaled in the sport for several decades.

The team played some in Canada but the most notable occurrence of Wright’s tenure in the league was his 1874 brainchild to tour the British Isles. It was an ill-conceived venture from the start, seemingly more of a personal dream than a wise professional plan, and it resulted in financial disaster. If the ever-frugal and business-minded Wright was willing to accept that, he at least desired to see the game that he championed catch fire in the land of his birth and ancestry (and a noble ancestry it was, at that, consisting of an Earl and a Grand Master in the Knights Templar). Due to an incompetent agent in England and the refusal of the English to replace their beloved game of cricket with this American stepchild called baseball, that hope failed as well. Upon his return, Wright was despondent; “We had an early frost,” he wrote a friend. “I feel frosty.” 7

The financial impact on the league was devastating, as it deprived the NA of both the Red Stockings and the Philadelphia Athletics, the two best clubs in the league. In 1876, the league was overthrown by the National League that exists to this day. Wright played a key role in this founding because he realized the hopelessness of the NA and the necessity of establishing a league that consisted of strong western clubs and not just Eastern dominance.

Reminiscent of the beginning of the NA, the Boston club (the “Red Caps” now, in deference to the upstart Cincinnatis) underachieved in the National League’s inaugural year and then went on to win two consecutive championships. The clubs were noted for their accomplishments despite a weak lineup, furthering Wright’s status as a superior manager. Noted one newspaper in 1886, “It is true Mr. Wright is not infallible, and he is apt to err, just as any other person in his particular profession will blunder, but Mr. Wright will make 49 good ones to every bad one.”8

By 1881, however, the club’s fortunes had eroded, and Wright had tired of being unappreciated in Boston. So he moved to nearby Providence to head the Providence Grays. He did reasonably well, most notably for historical purposes, for he instituted the concept of a farm system. With salaries higher than management preferred, Wright thought it would be beneficial to assemble a club of amateurs to play on the Providence grounds while the first nine was on the road; he could use the second nine as a breeding ground for talent that could replace senior members in case of injury or poor play. Though such an institution was not to be popularly adopted for several decades, Sporting Life plainly stated in 1883 that Wright was “the father of the ‘reserve club’ system.”9

In 1884, Wright left Providence to take over the woeful young Philadelphias. He instantly improved the club, but never attained a championship during his 10-year tenure at the head of the club. Management failed to pay players – and Wright, for that matter – any more than was absolutely necessary, and the manager was forced to do his best with the talent available.

One way of improving the talent was his promotion of what we now know as “spring training,” then referred to as a “southern trip.” Wright first took his club south in 1886 with the idea that such a warm-up would give the Philadelphias an advantage over other teams by starting off with six weeks of play under their belts as opposed to entering the season fresh. The plan worked just as he expected, and other teams began to follow suit so that by 1890 every club went south in the spring.

In late May 1890, Wright was suddenly struck with catarrh of the eyeballs and was rendered blind. It would take until the next March for him to regain his eyesight, but the process in-between was very painful and emotional for him, his family, and the baseball community. When he came back to manage with partial sight late in the 1890 season, he was received with great applause, but privately pitied for his weathered appearance.

To make matters worse, Carrie suffered a nervous breakdown soon after Harry went blind and was unable to leave her bed. After a long illness, Carrie passed away on February 5, 1892, to Harry’s tremendous grief. However, by July 1893 he was engaged to be married, and was subsequently wed in January 1894. His bride’s name is not known for certain, but it is thought by descendants to have been his first wife’s sister, Isabelle Fraser.10 If so, that may explain the intense bitterness harbored towards her by Carrie’s children, who considered her a nasty stepmother.

Matters weren’t going well with the Philadelphias, either. Throughout his tenure in the city, Wright had always had trouble with the management of Al Reach and especially Colonel John I. Rogers. Rogers micromanaged the club and publicly and privately attacked Wright’s disciplinary tactics, despite all evidence against his criticisms. After the 1893 season, the Philadelphias chose not to renew Wright’s contract, a move loudly protested by the Philadelphia press and fans.

The National League also regretted this move, and sought to compensate its old friend by creating the token position of Chief of Umpires. It was known that this sinecure would be Wright’s for life and would be abolished after his death. In substance, it merely consisted of watching over umpires and evaluating their performances, though this end of the job did not seem to be scrutinized by the league.

Wright died on October 3, 1895, after contracting a serious illness in his lungs. After being diagnosed on September 21, he tried to relieve the problem by inhaling the salty air of Atlantic City, a favorite vacation spot, but he there died the day after an operation.11

“No death among the professional fraternity has occurred which elicited such painful regret,” groaned sportswriter Henry Chadwick.12 Perhaps one may not understand today the extent to which his contemporaries revered Wright for his contributions to the game. In fact, the Society for American Baseball Research revealed a 1999 poll of its members that rated Wright as the third greatest contributor to 19th century baseball, behind Chadwick and Albert Spalding. Interestingly, in November 1893 The Sporting News edition noted that Wright’s only competitor for such a title was Cap Anson.

“[Harry Wright was] the most widely known, best respected, and most popular of the exponents and representatives of professional baseball, of which he was virtually the founder,” Chadwick commented upon his death.13 (This was not merely an exaggeration upon the occasion of his death; an 1886 newspaper also referred to him as “undoubtedly the best known baseball man in the country,”14 Even Rogers, his determined enemy, declared, “It has therefore truly been said, that so identified was he with the progress and popularity of the game its history is virtually his biography.”15

To honor his memory, the National League held a “Harry Wright Day” on April 13, 1896, from which all proceeds were to go towards building a memorial upon Wright’s gravesite. Wright himself had tipped his hat to the old league before his death by decreeing in his will that his personal writings be donated to its archives.

Wright was elected to the Hall of Fame in 1953 by the Veterans Committee, much later than his brother (1937), and much longer than many thought that he should have had to wait. His son, Harry II, blamed the new mentality of baseball that preferred sluggers and men of brawn to the scientific batter and the great minds.16

This biography is included in “Boston’s First Nine: The 1871-75 Boston Red Stockings” (SABR, 2016), edited by Bob LeMoine and Bill Nowlin.

Sources

Author’s correspondence with Halsey Miller Jr.

Harry Wright Correspondence

Henry Chadwick Diaries, Volumes 23 and 24

Henry Chadwick Scrapbooks

Sporting Life

The Sporting News

Notes

1 Author’s correspondence.

2 Family records provided by Halsey Miller Jr.

3 Henry Chadwick Scrapbooks.

4 Both citations are from clippings in the Chadwick Scrapbooks.

5 Ibid.

6 The Sporting News, December 12, 1895.

7 Harry Wright correspondence, September 15, 1874, to William Cammeyer.

8 Henry Chadwick Scrapbooks.

9 Sporting Life, December 12, 1883.

10 The Sporting News, 1890-94.

11 Chadwick Diaries, Volume 23.

12 Henry Chadwick Scrapbooks.

13 Ibid.

14 Ibid.

15 Ibid.

16 Author’s correspondence with Halsey Miller Jr.

Full Name

William Henry Wright

Born

January 10, 1835 at Sheffield, (United Kingdom)

Died

October 3, 1895 at Atlantic City, NJ (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.