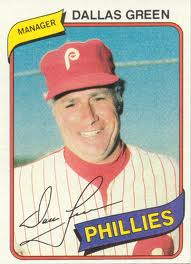

Dallas Green

“I express my thoughts. I’m a screamer, a yeller, and a cusser. I never hold back,” Dallas Green said after he was named manager of the Philadelphia Phillies in 1979.”1 With his no-nonsense confrontational style, attention to detail, unmatched work ethic, and passion for baseball in the “old-school” tradition, Dallas Green led the Phillies to their first-ever world championship in 1980 and forever sealed his reputation in the City of Brotherly Love. Those same qualities carried him through a competitive 13-year career in Organized Baseball as a hard-throwing pitcher in the 1950s and 1960s, including four months pitching out of the bullpen for the 1964 team.

“I express my thoughts. I’m a screamer, a yeller, and a cusser. I never hold back,” Dallas Green said after he was named manager of the Philadelphia Phillies in 1979.”1 With his no-nonsense confrontational style, attention to detail, unmatched work ethic, and passion for baseball in the “old-school” tradition, Dallas Green led the Phillies to their first-ever world championship in 1980 and forever sealed his reputation in the City of Brotherly Love. Those same qualities carried him through a competitive 13-year career in Organized Baseball as a hard-throwing pitcher in the 1950s and 1960s, including four months pitching out of the bullpen for the 1964 team.

George Dallas Green was born on August 4, 1934, in Newport, Delaware, a community of fewer than 1,000 inhabitants in the northern tip of the state, less than 35 miles from Philadelphia. His parents, George and Mayannah (Jones), both born in Delaware to working-class families, had three children, Thelma, Dallas, and Carole.2 The children grew up in lean times, the latter part of the Great Depression and the World War II years. They were raised by humble and diligent parents of German and Irish stock. George ran a garage and his mother was a homemaker who also did piecework. Dallas enjoyed sports, especially basketball, and baseball. When he was growing up, Philadelphia fielded two major-league baseball teams, but Dallas was an unabashed Phillies fan even though they were consistently among the worst teams in baseball in the 1940s. He recalled going to see the Phillies play in Shibe Park as a youngster, and also seeing Robin Roberts pitch for the Wilmington Blue Rocks in 1948, his first minor-league season.3

A natural athlete, Green played Little League, American Legion baseball, and high-school ball at Conrad High School in Newport, where he starred on the baseball team as a right fielder, and the basketball team, which he led to an undefeated season his junior year. Local legend has it that because of his height (6-feet-5) and long arms, he acquired the nickname Spider. Green attracted the attention of baseball and basketball coaches at the University of Delaware and was offered a scholarship to play both sports. Robert R.M. Carpenter of the wealthy Du Pont family of Wilmington, Delaware, owner of the Phillies at the time, was a major donor to the athletics program at the university and sponsored scholarships specifically for athletes. Green, whose parents did not attend college, jumped at the opportunity to pursue his dream at a time when because of the short college baseball season then prevalent, few serious major-league baseball prospects went to college to hone their skills. Playing for coach Bob Siemen on the varsity squad in 1954 and 1955, Green was a starting pitcher and right fielder. In 1955 he led the team with a 6-0 record and a 0.88 earned-run average.4 Named to the NCAA District 2 All-Star team, he attracted the attention of local scouts.5 Longtime Phillies scout Jocko Collins signed Green to a contract after his junior year, which made him ineligible to continue playing college basketball.6

Assigned to the Phillies’ Class B affiliate in the Carolina League, the Reidsville (North Carolina) Phillies, Green struggled. Having spent his entire life in Newport, he found himself in an unfamiliar state and was not prepared to face batters who already had two or more years of minor-league experience. With a 10.06 ERA in 17 innings pitched, he was sent to central Illinois to pitch for the Mattoon Phillies in the Class D Mississippi-Ohio Valley League.7 Used primarily as a starter, Green pitched much better against competition his own age. In his first start, on July 31 against Kokomo, Giants, he tossed a four-hitter and won, 7-2. More impressive were his fastball and 14 strikeouts.8 Averaging more than a strikeout per inning, Green won four of seven decisions, but struggled with his control and walked 42 in 55 innings.

Because the Phillies had not been able to duplicate the success of their surprising pennant in 1950, owner Carpenter wanted more attention given to developing future players. The front office was impressed with its big, 6-foot-5, 210-pound, hard-throwing right-hander and invited him to a three-week baseball camp and school for top prospects in 1956 led by manager Mayo Smith and scout Ben Tincup, who served as pitching coach.9 After the camp, Green was optioned to the Salt Lake Bees in the Class C Pioneer League. There Green pitched consistently if not spectacularly for player-manager Frank Lucchesi, with whom he subsequently forged a long professional relationship. Green struck out a season-high 16 in a victory over Magic Valley on September 1 on his way to leading the league in strikeouts with 226, but also in walks (187).10 With his 17-12 record, he was named the league’s rookie of the year.11

After Green’s second rookie camp, in 1957, the Phillies thought he was ready for Triple-A competition and sent him to their affiliate in the International League, the Miami Marlins. But after two poor outings he was reassigned in early May to the High Point-Thomasville Hi-Toms in the Class B Carolina League, where he was reunited with Lucchesi. On his way to a 12-win season, Green exhibited his trademark temper when he was involved in a bench-clearing brawl against Winston-Salem in midseason.12

In 1958 Green was invited to his first Phillies spring training after another excellent showing in his third rookie pre-camp.13 Mayo Smith and pitching coach Bill Posedel saw great potential in his fastball. Green was again assigned to Miami, where he pitched the entire season with the team’s top young prospects, as well as 51-year-old Satchel Paige. After a slow start, Green was more comfortable in the second half of the season and won five of his last eight decisions on his way to a 7-10 record. However, breaking into the starting rotation on the 1958 Phillies squad was a tough task for any young pitcher. Other than Robin Roberts, who was 31, the team boasted four experienced starters under 30, Ray Semproch, Jack Sanford, Curt Simmons, and top prospect Don Cardwell.

After yet another rookie camp in 1959, Green was disappointed when he was assigned to the Buffalo Bisons, the Phillies’ new affiliate in the International League. With great determination and an intimidating presence on the mound, Green was the Bisons top hurler in the first month of the season, posting a 5-1 record with four complete games in his first six starts.14 With the Phillies pitchers struggling, Green might have had a chance for promotion had he not come down with arm and shoulder miseries in mid-May that forced him to miss more than two months.15 Though he returned at the end of the season to help lead the Bisons to the International League championship, Green would be beset with shoulder and arm problems for the rest of his playing career and never achieved the success the Phillies had anticipated.

During the offseason, Green rehabilitated his arm while serving as an assistant basketball coach at the University of Delaware.16 He was an excellent basketball player and had he not chosen baseball, he probably could have pursued a career in basketball. At the University of Delaware he was all-conference his junior year, and many considered him the team’s best player. Even after signing his first baseball contract, he played in the semipro Suburban Major Basketball Association in the Philadelphia-Wilmington area during the 1955-56 and 1956-57 seasons, starring for Canby Park and Media AA.17

The Sporting News speculated in the offseason that Green “could win a job” with the Phillies in 1960. After spring training he was among the last to be cut, and was assigned again to Buffalo.18 With the Phillies foundering in last place in the National League, 17 games out of first place after just 57 games, Green was promoted in mid-June. He made an inauspicious major-league debut in a June 18 start in San Francisco in which he was the losing pitcher, giving up six earned runs and issuing four bases on balls in 5? innings. On the 23rd he pitched better but was not tagged with the loss in a losing game. In his third start, on the 28th against the reigning World Series champion Los Angeles Dodgers, he pitched one of his two career shutouts, surrendering just three hits in a 2-0 victory at Connie Mack Stadium.

Green pitched well through July and posted four complete games in his first seven starts. After his fifth complete game, in which he gave up seven runs in a loss to the Cubs on August 14, he was moved to the bullpen, where he toiled the rest of the season. Proving his “value as a spot starter and reliever,” Green concluded his rookie season with a 3-6 record and 4.06 ERA in 108? innings, and anticipated an even better 1961.19

Green had an impressive spring training, and manager Gene Mauch named him to the starting rotation. In his first start of the season, Green tossed a five-hit shutout over the Giants in San Francisco. “That’s harder than he threw all last year,” said Mauch after the “brilliant” performance by the 26-year-old Green. Green had command of his fastball and curve, and revealed, “It’s the first time in several years that I can throw without pain.”20 But his shoulder and arm problems soon resurfaced and he lost his velocity.21 After his fourth consecutive ineffective outing, on May 2, he was relegated to the bullpen, where he remained the rest of the season, making just three additional starts. While the Phillies limped to a 47-107 record, their worst since 1945, Green managed just two wins all season and saw his ERA rise to 4.85.

During the offseason, Green had an operation to treat a hernia that had kept him out of the military service in 1957.22 Though The Sporting News touted him as the “hardest worker in camp,” he was also described as “hardest pressed veteran.”23 At 27, Green was entering his prime pitching years; however, his star was being eclipsed by other rising pitchers, among them Chris Short, Jack Hamilton, Art Mahaffey, and Dennis Bennett, all of whom had secured positions in the starting rotation during the course of the season. Green pitched in long relief in the first half of the 1962 season and then as the fifth starter in the second half. On August 14 he had his longest career outing, a 10?-inning effort in New York against the expansion Mets, giving up just one earned run in a no-decision. He split his 12 decisions and had an above-average 3.83 ERA for a Phillies team posting its first winning record since 1953.

When the 1963 season began, Green was one of only six players remaining from the 1960 team. With a changing roster and another strong pitching staff, he began the season in the bullpen and put together his most effective year in the major leagues. He started the season with seven consecutive scoreless relief appearances, then he saw action as a spot starter throughout the year, twice registering two complete games in a row. On June 23 against the Mets in New York, Green gave up a fifth-inning home run to Jimmy Piersall who celebrated his 100th career homer by circling the bases running backward. Green’s highlight of the season may have been his complete-game, 6-1 victory over the eventual World Series champion Los Angeles Dodgers and Don Drysdale on September 15. Green finished the season with a career-high seven wins in 12 decisions and a career-low 3.23 ERA.

Beginning the 1964 season, his tenth in professional baseball, as the player with the longest active tenure with the Phillies, Green had a bittersweet campaign: He witnessed the team’s transformation from cellar-dwellers to pennant contenders, but his own season was something of a disaster. Slated once again for bullpen duty, Green joined Johnny Klippstein, Ed Roebuck, and Jack Baldschun to form one of the most intimidating and hard-throwing relief corps in baseball. However, in late June Klippstein was sent on waivers to the Minnesota Twins, and then on July 25 Green experienced the worst day of his baseball career. After he gave up six hits and four runs (two earned) in a loss to the St. Louis Cardinals, Mauch told him that he was being demoted to the minors. A lifelong Phillie, Green was stunned, disappointed, and mad. “We were going for our first pennant in years,” he remembered. “We had a pretty good team and it looked like we were going to wrap it up. It really hurt me. I just felt crushed.”24 Just about a week shy of his 30th birthday, Green was at a crossroads in his career and wondered if he should continue playing baseball. With great reluctance, he reported to the Triple-A Arkansas Travelers and was reunited with his former manager Frank Lucchesi. After pitching well in Little Rock, posting four wins in five decisions, Green was recalled in September, only to experience firsthand the agonizing and infamous Phold. He finished with a 2-1 record with an unsightly 5.70 ERA.

In his last three years as a player, Green was shuttled unceremoniously between the major leagues and minor leagues for three different organizations. The day before the 1965 season opened, the Phillies sold him to the expansion Washington Senators. Green, still smarting from his demotion the year before, looked forward to the change in scenery and anticipated pitching regularly.25 After just six appearances and 14? innings, he was returned a month later to the Phillies, who optioned him to Arkansas. On a staff that boasted future major leaguers Fergie Jenkins and Grant Jackson, and 19-year-old Rick Wise, Green was the Travelers’ most effective starter with 12 wins and served as a mentor to the young staff.

Not ready to retire, Green accepted the Phillies’ invitation to come to spring training in 1966 as a nonroster player, after which he was optioned to the their new affiliate in the Pacific Coast League, the San Diego Padres, managed by Lucchesi. In late July the Mets purchased his contract, but after four ineffective appearances sent him to the Triple-A Jackson Suns. When Green refused to report to the Suns, the Mets sold him back to the Phillies, who assigned him to San Diego.26 After a month of pitching inactivity, Green won his 100th game in professional baseball on his return to the Padres.27 He went 14-9 for the season.

Well respected by Phillies owner Bob Carpenter and general manager John Quinn, Green was named player/pitching coach of the Reading Phillies in the Double-A Eastern League. To his great surprise, he found himself in a strange position when his boyhood idol, former Phillies superstar and future Hall of Fame pitcher Robin Roberts attempted a comeback at the age of 40 with Reading after having been cut by the Chicago Cubs. Green, in his often overlooked but marvelously understated humor, quipped “What can I tell Robin Roberts about pitching? … I’m just making certain that he stays in his ‘shell,’ that good, smooth low motion he’s always had.”28 Green also showed that he could still pitch, albeit against Double-A players, going 6-2 and posting a 1.77 ERA. Less than 2½ months from being a five-year veteran, Green was recalled by the Phillies in late June and remained on the team long enough to qualify for a pension.29 He retired as a player at the end of the season with a career record of 20-22 and a 4.26 ERA. He posted an 89-64 record in the minor leagues.

From 1968 until his resignation as Phillies manager in 1981, Green moved from being a manager in the low minor leagues to being a baseball executive and ultimately to being the first manager in Phillies history to win a World Series. He began by managing Huron in the Northern League, then, with Pulaski in the Appalachian League, won a Rookie League championship and was named co-manager of the year.30 But Green wanted to pursue a career as an executive. Named the assistant farm director under farm director Paul Owens, Green learned the intricacies of scouting, running farm clubs, and especially evaluating talent.

In the midst of the Phillies’ fifth consecutive losing season in 1972, owner Bob Carpenter made radical changes in the front office. He fired general manager John Quinn and named Owens to succeed him. Green was promoted to farm club director, making him the first former Phillies player to hold a major executive position with the club since Carpenter bought the team almost 30 years earlier. Green made changes including a new grading system for evaluating talent and a new scouting structure that helped lay the foundation for the Phillies’ successes from the mid-1970s through the mid-’80s.31 He was named director of minor-league scouting in 1974, a position he held until 1979, and directed the Phillies’ amateur drafts.

After three consecutive first-place finishes and subsequent losses in the National League Championship Series, the Phillies floundered under easygoing manager Danny Ozark in 1979. With the team in fifth place, Ozark was fired and Green was given an opportunity to manage, his first field experience since piloting during the 1967 and 1968 short seasons in the low minors. “Dallas is going down on the field on an interim basis,” said GM Owens, “but don’t rule him out for next year.”32 Wearing number 46 from his playing days as a pitcher with the team, Green ignited the Phillies to an impressive 19-11 finish, yet stressed, “Being a general manger is my goal.”33

After three consecutive first-place finishes and subsequent losses in the National League Championship Series, the Phillies floundered under easygoing manager Danny Ozark in 1979. With the team in fifth place, Ozark was fired and Green was given an opportunity to manage, his first field experience since piloting during the 1967 and 1968 short seasons in the low minors. “Dallas is going down on the field on an interim basis,” said GM Owens, “but don’t rule him out for next year.”32 Wearing number 46 from his playing days as a pitcher with the team, Green ignited the Phillies to an impressive 19-11 finish, yet stressed, “Being a general manger is my goal.”33

Pressured by both Carpenter and Owens, Green reluctantly accepted reappointment as manager after the season. Though he managed only two seasons, they were among the most memorable in Phillies history, defined by winning, controversy, and confrontation. Green thought his players had grown soft and complacent under Ozark’s congenial manner and promised substantial changes in spring training. “It’s not going to be a country club; you can count on that. It’s going to be tough,” he said. “It’s our job to push them and we plan to do that.”34

Throughout his two seasons, Green chewed out his players for mental errors, poor execution, and being out of shape. He had high-profile confrontations with many players, including Greg Luzinski, Larry Bowa, Garry Maddox, Bake McBride, and Ron Reed. One anonymous player said that Green acted like a drill sergeant yelling and screaming and “even watches to see how many beers you drink after a game.”35 But his method produced results. Picked to finish no better than third or fourth in the NL East, the Phillies won 23 of their last 34 games to capture the division title. Then, after beating the Houston Astros in the NLCS, the Phillies defeated the Kansas City Royals in six games in the World Series. Green pushed his players and openly encouraged fierce competition among them. “We hated him,” catcher Bob Boone said. “He was driving us crazy. I don’t know if it was a unique approach, but it was a relationship that worked.”36

After a chaotic 1981 season in which the Carpenter family sold the Phillies and the baseball strike forced the cancellation of one-third of the season, Green was named executive vice president and general manager of the Chicago Cubs, recently sold to the Tribune Company. Green promised a change in culture for a team that had not had a winning record since 1972. “Building a New Tradition” was his slogan to attract new fans to Wrigley Field, which had seen its attendance drop to less than 10,000 per game in 1981. “We’re going after baseball fans,” Green said, but many bristled at his new approach. As general manager he concentrated on replenishing the farm system and orchestrated many successful trades, among them acquiring future Hall of Famer Ryne Sandberg from the Phillies, and Rick Sutcliffe, who directly contributed to the Cubs’ first-place divisional finish in 1984 and first postseason berth in 39 years, for which Green was named The Sporting News’ National League Baseball Executive of the Year.

But the Cubs managed only that one winning season during Green’s six-year tenure, which was also marred by a power struggle with team president Jim Fink and the city of Chicago over ordinances prohibiting the installation of lights at Wrigley Field. Citing the need for night games to generate much needed revenue, Green threatened at various times to close down the park and play at Comiskey Park, or even to build a new ballpark in the northwest suburbs if the city did not allow the club to install lights.37 The city finally acquiesced and lights were installed in 1988, a year after Green resigned his position.

Green concluded his managerial career by piloting both New York teams, the Yankees and the Mets. Yankees owner George Steinbrenner hired him as manager in 1989, but the experiment lasted only 121 games. From 1993 to 1996 Green led the talent-poor New York Mets, who were at their nadir after successful years in the mid- to late 1980s. As a manager, Green won 454 games and lost 478.

A baseball lifer, Green served three successive Phillies general managers, Ed Wade, Pat Gillick, and Ruben Amaro, Jr. (the incumbent as of 2013), as a special assistant after managing the Mets. He experienced the Phillies’ ascension to the pinnacle of success once again with their World Series championship in 2008.

In 2004 the Philadelphia chapter of the Baseball Writers Association of American established the Dallas Green Special Achievement Award for meritorious service by a player or member of the Phillies organization. In 2006 Green was inducted into the Philadelphia Phillies Wall of Fame at Citizens Bank Park.

Green was married for more than 50 years to his wife, Sylvia (Taylor) Green. They met at the University of Delaware. They had two daughters, Dana and Kim, and two sons, Douglas and John, who played minor-league baseball, and was a scout.

On January 8, 2011, tragedy struck the Green family when their granddaughter Christina Taylor Green, John’s 9-year-old daughter, was among six people fatally shot, and 14 injured, including Congresswoman Gabrielle Giffords, by a gunman in Tucson, Arizona. Major League Baseball expressed its sorrow to the Green family, and all of the victims, with a tribute before the 2011 All-Star Game. “[Baseball] has helped me, because you sink yourself into the work,” Green said of how he dealt with the tragedy.38

Green died at age 82 on March 22, 2017, in Philadelphia.

A version of this biography is included in the book “The Year of the Blue Snow: The 1964 Philadelphia Phillies” (SABR, 2013), edited by Mel Marmer and Bill Nowlin. For more information or to purchase the book in e-book or paperback form, click here.

Notes

1 The Sporting News, September 22, 1979, 18.

2 www.Ancestry.com.

3 Phillies Phollowers: http://philliesphollowers.mlblogs.com/2010/05/08/interviews-with-dallas-green-gary-sarge-matthews-and-virginia-ventura-marina/.

4 The Sporting News, June 22, 1955, 37.

5 Huntingdon (Pennsylvania) Daily News, June 4, 1955, 4.

6 The Sporting News, May 24, 1961, 13.

7 All minor- and major-league season statistics have been verified on Baseball-Reference.com. www.baseballreference.com

8 The Sporting News, August 10, 1955, 37.

9 The Sporting News, March 14, 1956, 23.

10 The Sporting News, October 24, 1956, 17.

11 The Sporting News, September 12, 1956, 37.

12 The Sporting News, June 26, 1957, 39.

13 The Sporting News, March 26, 1958, 10.

14 The Sporting News, May 27, 1959, 29.

15 The Sporting News, August 5, 1959, 32.

16 The Sporting News, October 14, 1959, 15.

17 Chester (Pennsylvania) Times, December 5, 1955, 22.

18 The Sporting News, October 14, 1959, 15.

19 The Sporting News, September 28, 1960, 22.

20 The Sporting News, April 26, 1961, 12.

21 The Sporting News, June 14, 1961, 14.

22 The Sporting News, April 10, 1957, 30.

23 The Sporting News, April 18, 1962, 10.

24 The Sporting News, November 8, 1980, 46.

25 The Sporting News, April 24, 1965, 17.

26 The Sporting News, September 3, 1966.

27 Ibid.

28 The Sporting News, May 20, 1967, 5.

29 The Sporting News, October 7, 1967, 37.

30 The Sporting News, September 6, 1969, 42.

31 The Sporting News, December 9, 1972, 50.

32 The Sporting News, September 22, 1979, 19.

33 Ibid.

34 The Sporting News, February 16, 1980, 40.

35 The Sporting News, May 17, 1980, 17.

36 Larry O’Rourke, “Dallas Green and the 1980 Phillies,” The Morning Call (Allentown, Pennsylvania), June 18, 2000.

37 “Cubs Mull Move to the Suburbs,” Milwaukee Sentinel, June 27, 1985, 8.

38 Hal Bodley, “Baseball Helping Green’s Slow Healing Process,’ MLB.com. http://philadelphia.phillies.mlb.com/news/article.jsp?ymd=20110216&content_id=16654918&vkey=news_mlb&c_id=mlb.

Full Name

George Dallas Green

Born

August 4, 1934 at Newport, DE (USA)

Died

March 22, 2017 at Philadelphia, PA (US)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.