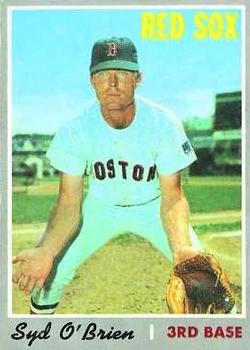

Syd O’Brien

Infielder Syd O’Brien was one of three brothers, all of whom signed to play baseball for the Boston Red Sox. Syd was the first to sign, and the only one of the three to make it to the big leagues.

Infielder Syd O’Brien was one of three brothers, all of whom signed to play baseball for the Boston Red Sox. Syd was the first to sign, and the only one of the three to make it to the big leagues.

His mother helped land three men on the moon.

Syd was born in Compton, California, on February 18, 1944 and played Little League, Colt League, Pony League, and American Legion ball, as well as both baseball and football at Millikan High School in Long Beach, from which he graduated in 1962. He went on to Long Beach City College and played baseball there, part of the team that won the California state junior college championship in 1963. Prior to the 1964 season, he was signed by veteran Boston Red Sox scout Joe Stephenson.

In a July 1963 prospect report, Stephenson wrote: “Player has shown good improvement. Better than average arm and running speed. Where he has shown the most improvement has been his hitting. Makes good contact and has a quick bat. At present his father is asking too much money ($20,000) or will stay in college. Fields ground balls well and has good range. Hustles all the time. Will follow.”

But Stephenson didn’t wait long. On September 12, he filed a report saying that he had signed O’Brien to a Wellsville contract, to report in the spring of 1964 for a salary of $500 per month. His report read: “Watched player all summer at 3rd base. Makes all the plays — is especially good at coming in on slow hit balls or swinging bunts and throwing men out. Accurate and better than average throwing arm. Knows how to run bases and is good slider. Has good hands and could play shortstop because of his speed. Where he has improved is with the bat. Always made good contact.”

O’Brien’s father, Lloyd O’Brien, believed Syd would be able to earn what he’d been seeking. Stephenson’s report said: “Player to participate in the Progress Bonus Payments etc. Upon approval of this contract by the Nat’l Assoc. player is to receive a bonus of $15,000 (Fifteen Thousand). Player is to receive a bonus of $2500 (Two Thousand Five Hundred) if with this club, or any assignee thereof, 90 days of the Championship season, unless given his unconditional release prior thereto.”1

O’Brien batted right and threw right, stood 6 feet and a half-inch and was listed at 182 pounds. He was given the name Sydney because a man by the name of Sydney Robinson had once saved his father’s life.2 That happened during World War II in the South Pacific where Lloyd O’Brien was in the Army with the combat engineers.3

“I had a great family,” Syd recalled in 2018. “I was one of the fortunate ones. My parents would do anything for the family. I didn’t know any difference when I was a kid. Everybody would say how lucky I was to have such a great family. I thought, ‘Doesn’t everybody have a family?’ I was really fortunate to grow up in such a loving and caring family. They seemed to be there all the time to help throughout my entire career.”

Both parents worked. “My dad [Lloyd] worked in a refinery and then he worked in a petrochemical plant. He was a welder. He worked with his hands.”

His mother, Marion Morse O’Brien, worked at North American Rockwell in Downey. “Mom couldn’t talk about it much at all. It was very secret at that time. She couldn’t even tell us what she did.” Later, she let it be known that she was the senior secretary for the person who was in charge of safety.4 A Boston Globe article in 1969 quoted her as saying, “In our department of the Apollo Division, we’re responsible for the environmental control system. That includes the oxygen and I don’t need to tell you how important that is.”5

“She did anything,” Syd recalled. “She was on roller skates as a carhop for Hody’s Drive-In in Long Beach when I was in high school. I used to go over there when I got my first car at 16. I’d drive over there and Mom would wait on us. It was really kind of cool. I had a pretty good childhood.”

Lloyd and Marion O’Brien also raised two other sons. Rod was four years younger than Syd, and Larry was two years younger than Rod. All three made their high school football and baseball teams. Lloyd O’Brien said of his sons, “Syd, you know about. Rod has been drafted by the Braves and Twins. He didn’t sign. He has a year to go at the University of Arizona. He plays first, second, and third…He wants an education, in business administration, before trying pro ball. Our youngest, Larry, is a lefty all the way. He hit .408 in high school this year and was drafted by Cincinnati. He hasn’t signed.”6 Larry had also been selected in the first round of the 1970 draft by the Montreal Expos, but declined to sign. Larry played first base and outfield and, when the Red Sox themselves drafted him in the secondary phase of the 1970 draft, was said to be “rated a better prospect than his brother Syd.”7

All three brothers were signed by Joe Stephenson, Syd said in his March 2018 interview. “Joe Stephenson signed me, and he signed my two brothers.” Rod played two seasons (1970 and 1971) for the Winter Haven Red Sox in the Florida State League. In just 27 games in 1970, he hit .136 but when given the opportunity to play in 120 games in the Class-A league in 1971, he homered 13 times, drove in 64 runs, and batted .251.

Larry played one season for the 1971 Greenville (South Carolina) Red Sox in the Class-A Western Carolina League. He appeared in 104 games and drove in 36 runs. He had a .244 batting average.

“Both of my brothers ended up being MRI technicians,” Syd said. “Both of them.”

O’Brien began his own professional career at Waterloo, Iowa, in the Class-A Midwest League in 1964. He appeared in 86 games and batted .320, with 11 homers and 55 RBIs. He also played in 15 games for Winston-Salem, with another two homers and six RBIs, batting .211 at the higher level of play. Under the draft rules at the time, a first-year player who was not brought up to the big-league team after his first year in organized baseball was subject to selection by another team for $8,000. The Red Sox had not protected O’Brien by calling him up to the major-league team; he was on the Seattle Rainiers roster, and the Kansas City Athletics claimed him in November.8 Robbie Robinson, A’s scout, believed O’Brien was “an outstanding major league prospect.”9

O’Brien married Joanne Frances Horalek on August 22, 1964.

In 1965, O’Brien played for Lewiston (Northwest League), batting .265 with 12 homers and 61 RBIs, and 21 games for Birmingham (.227/1/7), ending up on the Vancouver roster. O’Brien later said of his time with the Athletics, “How I hated that organization. They moved me all around and I never knew what was going on.”10

On May 12, 1966, the Red Sox-affiliated Toronto Maple Leafs reacquired O’Brien, trading Fred Holmes and Bob Duliba for O’Brien and two others.11 There was some suggestion later that there had been an “arrangement” of sorts between the two ball clubs; there was a Kansas City player that Boston had taken and later returned to K.C.12 O’Brien joined the Winston-Salem Red Sox, for whom he appeared in 102 games, batting .302 (with 10 homers and 43 RBIs), and got into 18 games for Modesto in the California League (.309/3/8).

O’Brien played Triple-A ball the next two years, for Toronto in 1967 and Louisville in 1968 (after the Red Sox moved their International League franchise there), both years playing under manager Eddie Kasko. He hit .255 in ’67 and .265 in ’68, with 10 homers and 60 RBIs.

In the spring of 1968, coming off Venezuelan winter league baseball, he was among Red Sox prospects — characterized as “a lot of nobodies” — hoping to make the team. The Boston Globe’s Ray Fitzgerald wrote, “And there’s Syd O’Brien, and of all the nobodies, he’s the most likely to succeed.”13

Both Jerry Adair and Joe Foy had been taken by Kansas City in the expansion draft, seeming to open up infield possibilities for O’Brien. “I feel I’m good enough to make it,” he said. “I’ve been playing second base, but third base is my natural position. And besides, I can play an acceptable brand of shortstop, even though I haven’t played there since high school.” He said he might have been called up after the 1968 season had ended in Louisville but he had been hit on the head by a pitch on September 3. “That was it. I was dizzy for a month. I couldn’t run. My equilibrium was off. But I feel fine right now and have been working out with Long Beach City College. No chance I’ll be gun shy.”14 He’d also spent the winter working at Douglas Aircraft. ‘My father-in-law, he was a short match there — they were the big shots. He would always give me a job. So I worked there for Douglas Aircraft right there in Long Beach. Sometimes I did drafting. One time I did master layout. One year I called myself a ‘corrosion control technician.’ I made that job description up — what we did was wash the airplanes.”15

In 1969, Syd O’Brien reached the big leagues, debuting with the Red Sox on April 15. In a game Boston was losing to Baltimore, 10-5, he pinch-hit in the eighth inning and struck out. The very next day, after Ken Brett had already given up five runs through three innings, O’Brien pinch-hit for him to lead off the bottom of the third and doubled off Dave McNally. Years later, he described that first big-league base hit as his biggest thrill in baseball.16 Two batters later, he scored. Up until the All-Star break, more than half of his appearances were as a pinch hitter or pinch runner. It was, of course, an ongoing challenge trying to be ready.

On April 29, he enjoyed the extra pleasure of playing a big role in the 2-1 Red Sox victory at Yankee Stadium. The Yankees had a 1-0 lead after six innings. O’Brien had come in to play third base in the fifth inning after Dalton Jones had hurt his left elbow taking a throw. In the top of the seventh, Tony Conigliaro doubled to left field to lead off. O’Brien then singled to left and drove in Conig, tying the game. He took third on a wild pitch, then scored the go-ahead (and winning) run two batters later when Joe Azcue grounded out to second base.

He wasn’t playing regularly, of course, and he admitted, “This waiting for a chance to play is driving me crazy. I was always a regular in high school and in the minors. It’s hard for me to sit and wait. Part of the problem is I’m sure I can do the job if I get the chance.”17 He was 24 and didn’t think he needed any more work in the minors. He tried to be primed and ready. “I may be sitting on the bench, but mentally I’m playing every game just like I think a manager would. I try to anticipate things. Mostly I’m looking for situations which might give a guy like me a chance — like as a pinch-runner. If I think I see a situation coming up where maybe we’re going to make a change on the bases, I deliberately leave the dugout and go down into the runway that leads to the Red Sox clubhouse. I try to get my body loose by running and bending. I figure that little edge might come in handy if I’m the guy the manger puts in the ball game.”18

Through July 15, O’Brien was batting .264. Manager Dick Williams then began to use him as a starter, most often at third base but sometimes at short and sometimes at second. On July 20, he homered in the fifth and tripled to drive in two runs in the bottom of the eighth; Boston beat Baltimore, 6-5.

By season’s end, he had appeared in an even 100 games, with 283 plate appearances. He hit .243 with a .287 on-base percentage. He homered nine times, scored 47 runs, and drove in 29.

The Red Sox needed a starting pitcher for 1969 more than they needed a utility infielder, and they traded O’Brien to the Chicago White Sox, along with a minor leaguer, for Gary Peters and Don Pavletich on December 13. In March 1970, Boston added Gerry Janeski to complete the transaction. Even a year after the trade O’Brien was said to have “one of the biggest fan clubs in Boston since Hawk Harrelson.”19

O’Brien played the full 1970 season with the White Sox. The team had a miserable season, losing 106 games and only winning 56. They went through three managers and even saw GM Ed Short fired on September 2. O’Brien was utility infielder with the team, but was used frequently, primarily at third base and second base, appearing in 121 games. It was the season in which he saw the most major-league action. He committed a team-leading 25 errors, but his batting average of .247 was quite close to the team average of .253. His 44 runs batted in ranked him fifth on the team. His eight homers also ranked fifth. It was his bat that attracted attention. One Boston sportswriter had written, “He never was mistaken for a Brooks Robinson in the field, but he did an acceptable job. The big thing he had going for him defensively was a good arm.”20 O’Brien had the winning base hit in a couple of games for the White Sox — the first game on July 24, and the game on August 8, and played key roles on offense in at least four others, for instance scoring the winning run on July 31.

There had been one incident when GM Short had sent O’Brien a bill for $17.50 for cracking his batting helmet by slamming it in frustration against the concrete runway after a May 17 doubleheader loss. His teammates started an “O’Brien Fund” and raised the money.21 Both catcher Ed Herrmann and O’Brien had been fined $100 for being five minutes late at curfew time.22

On November 30 he was traded again. Ken Berry and Billy Wynne joined him, the three of them sent to the California Angels for Tom Bradley, Tom Egan, and Jay Johnstone. He was seen as “three-way insurance” due to his ability to play multiple infield positions. “They’ve told me I’m an insurance policy,” he said. “Nothing more. That was disappointing. But it could have been worse. They could have traded me to Cleveland or Philadelphia.”23 If nothing else, he was close to home. His home in Cypress was about 10 minutes from Anaheim Stadium.

In 1971, O’Brien stuck with the big-league team the whole season. He wasn’t used quite as much, but still appeared in 90 games, mostly at shortstop (52 games) but fairly often as a pinch-hitter and occasionally as a pinch-runner. His batting average declined near the end of the season, and just dipped below .200, to finish at .199. He had a .247 on-base percentage and drove in 21 runs. His biggest hits were likely the two-run homer in the top of the 11th inning on May 7, beating the Indians, 4-2, and the come-from-behind two-run homer that beat the Red Sox, 5-4, on June 15 in Anaheim.

Over the offseason, O’Brien began taking acting lessons. Jerome Holtzman once called him “a handsome blonde Adonis.”24 Yes, he took lessons, O’Brien said years later. “Dick Enberg was always pointing to me, saying that he thought I could do anything — that I could act or whatever. So I tried. I went to acting school during the winter. We were just doing stage stuff, but we were being set up for TV things. And I found out it was one of the toughest things I’d ever done — to take somebody else’s words and put them in my own mouth and make them come out believable. I’m a pretty good salesman but that was hard for me to do. I didn’t pursue it, but, yeah, that was a learning experience.”25

For O’Brien’s part, he once said, “Baseball is a game. You’ve gotta be a little goofy to play it and you gotta have some fun, too.”26 He also took part in the annual Medical Benefit game of the Southern California Baseball Association. He did P.R. work in auto sales, in the computer field, and was studying investment counseling. “You had to do anything you could do during the winter. You’re only going to be there for four or five months and then back to spring training. You really just did anything that you could do. I just tried to do different things. At one point, I worked for a guy named Jim Snow who owned a car dealership. He used to give me a car to drive all the time, and I’d come over and sign autographs and things like that. I decided, ‘What the heck? I’ll try and sell cars.’ Well, I couldn’t do that either. I wasn’t good at selling people something that they really couldn’t afford. I bowed out of that, too. But everything was for a reason.”27

He had also started an investment group called Universal Competitors, to advise younger athletes on their finances. “When I signed,” he said, “I got $35,000 and it’s gone. I wish I’d had somebody eight years ago to help me invest my money.”28

O’Brien’s 1972 season saw him start the year with the Angels again, in the same role, playing all four infield positions at least once but with more than half his appearances in pinch capacities. He had 39 at-bats in 36 games but drew six walks and had an on-base percentage of .289 (his batting average was .179). He was briefly optioned to Salt Lake City, but a day or two later, on July 28, he was traded to the Milwaukee Brewers, with Joe Azcue, for Ron Clark and Paul Ratliff. For the Brewers, he hit .207 in 31 games, nine at third base and seven at second with the rest in pinch roles.

His final year in baseball was 1973. He started the season with Evansville but was traded in April to the Charleston Charlies (a Pirates affiliate) and split his regular-season time in the Triple-A International League between Charleston and (after his contract was sold in July) the Toledo Mud Hens (a Tigers affiliate). An early hip injury put him on the shelf for several weeks. His combined league stats show him in 97 games with a .226 batting average. He even pitched in two games with a 63.00 ERA in two innings of work.

The writing was on the wall, though. It was time to seek another profession.

“I worked for a liquor distributor for a while — not for every long — and then I got into advertising. I sold advertising for two or three journals in the oil and gas industry. I had 11 Western states. That was pretty interesting. It was a pretty good job.

“And then I moved to Houston. It didn’t work out and I didn’t like Houston, either. I came back. I met a guy who had a steel company and did some reinforcing steel. Part of his program was post-tensioning with a housing project. I learned that, and then I decided I was making him way too much money and decided to go out on my own. I started my own company and I engineered, furnished, and installed post-tension systems for new homes — a lot of tract homes and for private homes. I did that for quite a few years until I retired and I moved up to Northern California. I’m in Placerville. Lake Tahoe, Sacramento.

I’ve been up here about 30 years. My brother Rod moved up here and then Larry moved up and this is where I wanted to be. My parents lived at Palm Desert but when I moved up here, they said, ‘What are we doing down here? Let’s move up there, too.’ So we’re all up here. That was great, when my parents were still alive. We moved my grandmother up here, too.”

Syd has been married three times, and his third marriage in 2000 to Nadine, a registered nurse who worked in cardiology for 30 years, has endured. He had three children of his own — Erin, Sean, and Kirsten. And Nadine had three children, too. Both Syd and Nadine are retired now, and living in Placerville. “I’m 74 right now. I’m in pretty good shape. I look like I’m 60. I work out three times a week. I go shooting at the range a lot. I like my guns. I live on a golf course and play golf. Life is good.”

“I’ve got all sorts of toys,” he says. “I’ve got three boats. I’ve got motor homes and fifth wheels and stuff. Everybody says, ‘Why don’t you go and do stuff?’ I said, ‘Listen, when I moved up here, I moved because I wanted to be here. I’m on vacation all the time!’ It’s beautiful here. I’m an hour and a half from Tahoe, 30 minutes from Sacramento. I can have my boat in the water at a beautiful lake, a reservoir, in an hour. I go out my back gate and play golf whenever I want. I belong to the club here. I’ve got a couple of old Corvettes. I still ride my Harley. I have lots of toys. I do.”

But O’Brien also gives back to the community. A few years before he met Nadine, when he was in his early 50s, he was diagnosed with bladder cancer in 1996. “My oncologist was Linda Bosserman, who was the head of the UCLA Medical Center for oncology. She told me, ‘What I’m going to give you might kill you, but we have no choice here. This is poison but if I don’t give this stuff to you, then you’re going to die.’ They gave me six months to live. I went through an extensive chemotherapy program.”

He beat the odds. “I did beat them, didn’t I? I sure did, and I’ve been cancer-free since except for some melanoma and stuff. But I lost my bladder in the meantime. At that point they had to take my bladder out and I had a urostomy. Well, no one knows I have a urostomy unless I tell them. I’ve been with the ostomy support group for quite a long time. I go to hospitals and I talk to people. I do what nurses call rounding — talking to patients. I’ve been trained to do this. I just have a knack for talking to people and finding common ground.

“I talk to the patients that are going in to surgery and those who are coming out. They might go in for a stomach problem and they learn they have a ‘blowout’ — the waste is going inside your body and it’s going to kill you. And so they wake up and they have an ostomy. They have a colostomy or something, and they’re scared to death. The doctors really use me a lot. I come in and I talk to them, talk to people about life after having an ostomy. It’s not something you’re going to die from. I just give them hope.”

He devotes time to visiting other patients outside the ostomy support group. The nurses will let him know about patients who don’t have family to come visit them. “I make sure to talk to those people first. They’re lonely. I tell them, ‘Listen, you’ve got to stay positive. Your body can’t heal unless you’re positive. A negative person’s body will heal, but it will heal very slowly. You’ll heal so much faster if you’re positive and have good thoughts.’ I did it right from the get-go. I said, ‘This is what people need from me.’”

Last revised: November 26, 2022 (zp)

Acknowledgments

This biography was reviewed by Norman Macht and fact-checked by Kevin Larkin.

Sources

In addition to the sources noted in this biography, the author also accessed O’Brien’s player file and player questionnaire from the National Baseball Hall of Fame, the Encyclopedia of Minor League Baseball, Retrosheet.org, and Baseball-Reference.com. Thanks to Rod Nelson of SABR’s Scouts Committee.

Notes

1 Thanks to Rod Nelson of SABR’s Scouts Committee for supplying the prospect reports written by Joe Stephenson.

2 Ray Fitzgerald, “Nobodies Vie for Berths at Sox Camp,” Boston Globe, March 3, 1968: 43.

3 Roger Birtwell, “For O’Briens, All Systems Go,” Boston Globe, July 21, 1969. In a 2018 interview Syd O’Brien said, “My dad and Sydney Robertson were buddies and they saved each other’s lives, as many a man did. It was not one particular time. It was a series of events that both of them had saved each other’s lives throughout the war. I was named after Sydney Robertson. He was a good friend of my dad’s, in the Army. They were friends afterwards also.” Author interview with Syd O’Brien on March 21, 2018. All quotations from O’Brien not otherwise attributed come from this interview.

4 Syd recalled an incident that understandably affected his mother greatly. “There was a time that two guys burned up. Two guys died in a mock…because the safety wasn’t as good as it should have been.”

5 Birtwell.

6 Ibid.

7 “Red Sox Draft Larry O’Brien,” Boston Globe, June 6, 1970: 18.

8 Oscar Kahan, “Majors Run Up $572,000 Tab to Draft 63,” The Sporting News, December 12, 1964: 5.

9 Joe McFuff,” There’s A Greenish Tinge to A’s Roster,” The Sporting News, December 12, 1964: 20.

10 Ray Fitzgerald.

11 “Deals of the Week,” The Sporting News, May 28,1966: 38.

12 Larry Claflin, “O’Brien Wielding Red Sox’ Hottest Bat,” The Sporting News, September 27, 1969: 16.

13 Ray Fitzgerald.

14 Fred Ciampa, “O’Brien May Be Ready for Sox Berth,” Boston Record American, February 12, 1969: 44.

15 Author interview with Syd O’Brien, March 21, 2018. O’Brien expanded a bit: “There was a lot of people getting laid off and all of a sudden, I get hired. I worked in the tool cage. They put me in the tool cage because there was an opening. Well, the tool cage is where everybody picks up their tools for the day and then brings them back. It’s kind of a center for whatever goes on in that little area. There were some things going on that I didn’t really want to get involved with. With people getting laid off and I was getting hired, they thought that I was a cop or something.”

16 A 1972 fact sheet in O’Brien’s player file at the National Baseball Hall of Fame.

17 Phil Elderkin, “’It’s Hard to Sit and Wait,” Christian Science Monitor, May 26, 1969: 11.

18 Ibid.

19 George Langford, “Jovial Syd O’Brien: Always Comes to Play, But Doesn’t Always,” Chicago Tribune, June 20, 1970: A2.

20 Fred Ciampa, “O’Brien Totes Hot Bat,” Boston Record, September 12, 1969: 27.

21 Jerome Holtzman, “O’Brien Blows Top — Cost is $17,50,” The Sporting News, June 6, 1970: 27.

22 “Curfew Violation Costs Herrmann $20 a Minute,” unidentified clipping dated July 25, 1970 in O’Brien’s player file.

23 Dick Miller, “O’Brien Life Three-Way Insurance for Angels,” The Sporting News, March 27, 1971: 31.

24 Jerome Holtzman, “Syd Standing Tall for Sagging Chisox,” The Sporting News, July 11,1970: 12.

25 Author interview with Syd O’Brien, March 21, 2018.

26 Dick Miller.

27 Author interview with Syd O’Brien, March 21, 2018.

28 Dave Distel, “No Place Like Home for O’Brien,” Los Angeles Times, March 18, 1971: F13.

Full Name

Sydney Lloyd O'Brien

Born

February 18, 1944 at Compton, CA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.