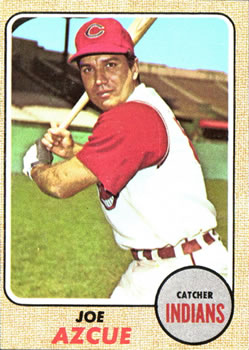

Joe Azcue

Joe Azcue caught just shy of 1,000 major-league baseball games for six different big-league teams — all but his first 14 games played in the American League. An All-Star with the Cleveland Indians in 1968, Azcue was solid on defense with a .992 lifetime fielding percentage.

Joe Azcue caught just shy of 1,000 major-league baseball games for six different big-league teams — all but his first 14 games played in the American League. An All-Star with the Cleveland Indians in 1968, Azcue was solid on defense with a .992 lifetime fielding percentage.

José Joaquín (Lopez) Azcue was born on August 18, 1939, in Cienfuegos, Cuba, where he was raised. “When I was small, we lived a very hard life,” he said, “but there was always food to eat. My father worked in a sugar cane processing plant in Cienfuegos — my home town — all day and had another job with a gasoline distributor. When I was 6 or 7 he got a responsible position with the gasoline distributor and we lived what you would call an upper middle class life from then on — or until Castro came along.”1

His father Joaquin worked for the Sinclair Corporation selling kerosene and alcohol as cooking fuels to grocery stores. The work was good enough that his mother Petra was able to keep house, taking care of Jose and his younger brother, Jorge, born in 1946. Now deceased, Jorge Azcue tried his hand at baseball, too, signing as a pitcher/first baseman with the Atlanta Braves organization. At one point, as he was starting out, he suffered a bad injury running to cover first base, tumbling over the bag, tearing up his left shoulder — his pitching shoulder. “In those days, there was no way to fix it.”2

Joe attended Champagnat High School in Cienfuegos where he played baseball, basketball, and soccer. He completed all but his senior year when he was signed to a professional baseball contract by Cincinnati Reds scout Camilo “Corito” Varona just before he turned 17. His bonus reportedly “included a catcher’s mitt and a $45 advance to be deducted from his monthly pay of $150.”3 Or as he later put it himself, “I got a glove and a Coca-Cola.”4

Champagnat was a private Catholic high school a half block from his house, run by the Marist Brothers, and Joe took English classes there, which made the challenge of acculturation less of a burden when he did come to the United States.

His first assignment was to play Class-D ball for the Douglas Reds in the Georgia State League in the summer of 1956. The team was managed to the pennant by Johnny Vander Meer. Azcue appeared in 57 games as outfielder and catcher, and hit .236. He also appeared in two games for the Moultrie Reds in the Georgia-Florida League.

In 1957, Azcue played in 123 games for the Palatka Redlegs (Class D, Florida State League), again under Vander Meer, where he hit .266. Azcue was catcher for the North team in the league’s North vs. South All-Star game.5

The 18-year-old Azcue trained with the Reds in the springtime of 1958 and was initially advanced to Class A. After 11 early-season games for Savannah, Georgia (he was 5-for-28), and a pulled back muscle, he spent most of the season catching in Wenatchee, Washington, playing for the Class-B Northwest League’s Wenatchee Chiefs. He hit for a .308 average in 84 games.

Returning to Savannah in 1959 with another year of development under his belt, he was more productive, batting .262 and driving in a career-high 51 runs in 113 games.

In Cuban League winter ball, Azcue — in his third year playing for the Cienfuegos Elefantes — saw his team win the pennant by a 12-game margin and then win six games without a loss in that year’s Caribbean Series staged in Panama. He was 3-for-4 in the final game on February 15, 1960.

In the 1960 season, Azcue was already being tabbed a “sure-fire big leaguer in the making” by his manager, Tony Castano.6 He stood an even six feet tall and was listed at 195 pounds that summer when he played in the Triple-A International League for the Cuban (Havana) Sugar Kings; the franchise relocated to Jersey City on July 13 as the Cuban Revolution unfolded. Historian Peter Bjarkman says the “actual situation…remains clouded at best” and that we may never know what truly transpired, but that the Havana club “was spirited away” to Jersey City.7 Azcue’s record was .270 in 97 games and he also experienced his major-league debut.

On August 1 he was called up to the Cincinnati club and catcher Dutch Dotterer was sent down. Two days later, manager Fred Hutchinson asked Azcue to catch the second game of a doubleheader against the Cubs at Wrigley Field. He batted seventh in the lineup and was struck out by Dick Ellsworth his first time up. In the top of the fourth, he came up again, with runners on first and third and one out. He singled to left field off Ellsworth, driving in one run to tie the game, 2-2. He grounded out his third time up; the Cubs won, 4-2.

Azcue played in five more August games, and eight in September. He drove in two more runs. He was 3-for-31 (.097) at the plate. Behind the plate, he handled 72 chances without an error. He threw out three of the six baserunners who tried to steal on him.

Many of the newspapers at the time called him Joaquin “Jake” Azcue; one dispatch said he enjoyed trumpet as a hobby.8

On December 1 his contract was purchased by the Milwaukee Braves. That winter (1960-61), he played his last games for Cienfuegos in Cuba. He hit .289 in 228 at-bats, with six homers and 38 RBIs.9 The Elefantes repeated as champions. After the winter season, he left Cuba for good.

Azcue had difficulty getting out of Cuba in the spring of 1961, having to travel via Mexico City, but he made it and spent the full season in the Triple-A Pacific Coast League with the Vancouver Mounties. He played in 82 games, batting .297 with 43 RBIs. Being assigned to a Canadian team may have helped him bring his family from Cuba. “It took me about eight months to get my parents and brother out of Cuba in 1961…I got them a visa through the Canadian government. They flew to Venezuela and then to Puerto Rico, where they are now,” he explained in 1970.10

He has never returned to Cuba, he said in early 2018. “There’s no reason to go back. Been there, done that. Back then, we had everything over there that we have over here. We had the Bank of Boston over there, the First National Bank, a Canadian bank.”11 And, of course, his father worked for the American petroleum company, Sinclair. There isn’t any pull to visit Cuba. Azcue has been in the United States since 1956.

That winter Azcue played in Venezuela for the Caracas Lions. Come mid-December, he was on the move again, traded by Milwaukee to the Kansas City Athletics on December 15 as part of a five-player deal.

This gave him the opportunity to get back to the big leagues and he spent the full 1962 season with the Athletics. Haywood Sullivan was manager Hank Bauer’s primary catcher that year, but Azcue got into 72 games, with 248 plate appearances. He hit .229 (.287 on-base percentage) with 25 RBIs, several of them in one-run games. One memorable game was on June 17 against Minnesota, a 10-6 win in which Azcue was 3-for-4 with two RBIs, and even stole home in the bottom of the fourth.

He began 1963 with Kansas City again, but after the first week of May — after going 0-for-4 in two major-league games — Azcue was optioned to Portland, back in the PCL. He played 10 lackluster games there, but then found himself traded on May 25 to the Cleveland Indians, with shortstop Dick Howser, for second-string catcher Doc Edwards and $100,000. Azcue settled in with the Indians and remained in Cleveland for six-plus seasons.

He caught most of the games for manager Birdie Tebbetts and the Indians once he reported at the end of May, taking over for catcher John Romano, who had suffered a broken hand, and had his best season in major-league baseball, hitting .284 with 46 RBIs in 94 games. He had a .992 fielding percentage, and even helped turn a league-leading 13 double plays as a catcher that year. He claimed his secret in handling pitchers was: “I tell ‘em, ‘Throw anything you want. I call it’.”12

He said that both general manager Gabe Paul and Tebbetts had known him since he was 15, and seen potential in him. He singled out Tebbetts: “He was a good manager. He was a philosopher. He came from the same school of catching as Mickey Cochrane, so all the stuff I knew about catching came from Cochrane and Tebbetts.”13

There were a couple of standout days. On August 8 in Baltimore, during the seventh inning of a scoreless game between the Indians and Orioles, Azcue stole home for what proved to be the winning run, and on August 18 he hit two home runs and drove in three in a 7-4 win over the Boston Red Sox. Of his five career stolen bases, two were steals of home. He’d won over Tribe fans; beginning in July, Plain Dealer sportswriters began to refer to him as “the immortal Azcue” because of how he carried on catching despite a stretch catching with just one eye, due to an infection in the other eye. “In this day right now, you’d be out of the lineup for two months.”14 The nickname stuck. In a poll conducted by the Plain Dealer in February 1964, asking who should be the Indians’ first-string catcher, Azcue won 2,180 votes to Romano’s 1,827.15

During 1964, he started high school all over again. Because he couldn’t return to Cuba, he had no way to prove he had a high school diploma, so he began to take correspondence courses for a U.S. high school diploma, hoping to become an electrical engineer after going on to college.16 His personality, wrote Hal Lebovitz, was of “a character with character. He’s a laughing, bouncy catcher who appears to have as few cares as a beachcomber.” But he had no time for frivolities such as television; he was busy taking his courses. His American-born wife, Judy, helped him with his English.17 She also gave him a shortwave radio for his birthday and he was able to follow broadcasts of amateur baseball in Cuba. “You should hear the announcer,” he said. “He always talks about how amateur baseball is best because players play better when they’re not paid. It’s ridiculous. The Cuban people don’t swallow all that.”18

How had they met? “She saw my picture in the paper when I got traded to Kansas City and said, ‘He’s going to be my husband.’ My brother told me there’s a girl who said that, and the first time I saw her, I said, ‘That’s it.’”19 As of the time of the 2018 interview, they have been married for 56 years.

During the offseason of 1964-65, Azcue worked for the publicity department of the Indians, even writing a humorous bylined column about the negotiations of Joe Azcue’s salary.20

His batting average dropped from .284 in 1963 to .273 in 1964, but then plunged to .230 in 1965. In early 1966, he said that Indians GM Gabe Paul seemed to pay too much attention to a player’s weight, but then said, “I agree with him. I was too fat last season.”21 He got up to a reported 212 pounds. Perhaps the saunas and other efforts paid off; after losing 20 or so pounds, he rebounded to hit .275 in ’66. He led the majors in baserunners thrown out stealing (28), cutting down 62% of the runners who attempted to steal on him.

As a catcher, he suffered all the usual bruised thumbs, and limbs, spikings, sore shoulders, and pulled muscles, as well as a couple of eye infections and other such maladies, but in his seasons from 1963 through 1970 he averaged just under 100 games per year.

He maintained a good sense of humor. The Wahoo Club — the Cleveland Indians booster club — had awarded him the “Golden Tomahawk” for 1966 as the most underrated player on the team. Not long before accepting the award in late April 1967, Azcue had been informed by manager Joe Adcock that Duke Sims would become the Indians’ first-string catcher for the ’67 season. “I’m still under-rated,” he cracked.22 As it transpired, the two shared duties during the season,

He had his best two seasons behind the plate defensively in 1967 and 1968, perhaps in part by taking advantage of the new video technology being introduced at the time. The cameras had been focused on hitters Vic Davalillo and Max Alvis but Azcue was catching in batting practice and saw that “when I went into my crouch before the pitch was delivered, I was OK. But when the ball was on the way, my seat dropped down. That blocked me from moving…if the pitch was in the dirt, I was sitting back instead of leaning forward to get my body in front of the ball.”23 Problem corrected, Azcue led all catchers in fielding percentage with .999 in 1967 and .996 in 1968.

In 1968 he played in 115 games, the most in his career, and hit for a .280 average with 42 runs batted in. He was named to the American League All-Star team by manager Dick Williams, the one time in his career he was accorded the honor. Tom Seaver struck him out in his lone at-bat. There was one other notable event in Azcue’s 1968 season, one which he might prefer to forget: on July 29, 1968, he hit into an unassisted triple play executed by Ron Hansen of the Washington Senators, the first one in the major leagues since 1927.

Perhaps trading Azcue when his value was at its highest, the Indians found an opportunity to acquire Ken Harrelson, and so dealt pitchers Sonny Siebert and Vicente Romo, and “veteran catcher” Azcue to the Boston Red Sox on April 19, 1969, for pitchers Dick Ellsworth and Juan Pizarro, and Harrelson. It was primarily Siebert for Harrelson; in anger, Harrelson announced his retirement but three days later changed his mind.24 Azcue caught two no-hitters in his career; the first had been Siebert, on June 10, 1966. The second came in 1970 when he caught Clyde Wright of the Angels on July 3.

The Sox had Russ Gibson as their primary catcher and welcomed Azcue as a backup, but moved him less than two months later. In 19 games with Boston, he hit .216. But he jumped the club on June 11, returning home to Kansas in anger because he was not being used. He went over Dick Williams’s head to complain to higher-ups, which didn’t sit well, either. Azcue was suspended and Williams let it be known that the Red Sox had already started the process of trying to trade him.25 He declared he would quit the game if they did not.26 It didn’t take long; Azcue was traded to the California Angels on June 15, straight up for catcher/utilityman Tom Satriano. Harold Kaese of the Boston Globe wrote that the Red Sox “may have traded him because of Dick Williams’ attitude toward club jumpers. He doesn’t want them back.”27

With the Angels, Azcue caught in most of the remaining games — 80, but only hit for a .218 average.

The following year — 1970 — he was a holdout in the springtime, but returned in time — reportedly for the same salary — and remained the Angels’ first-string catcher, appearing in 114 games, while getting his stroke back and batting .242. Though he again posted a very good .991 fielding percentage, he was charged with 10 passed balls by early June and was forced to cede first-string status for a while to younger catcher Tom Egan. By season’s end, Azcue had caught in many more games, but his 17 passed balls led the league. One of his best offensive games of the year was his 4-for-5 game against the Royals in Kansas City on June 26. He homered and drove in two; the Angels won, 5-4.

Azcue held out again in spring training. His contract was automatically renewed in early March, but because he didn’t sign his contract, he was placed on waivers on March 14.28 He’d been seeking a $5,000 raise, pointing out that only Thurman Munson and Ray Fosse had higher batting averages as catchers in the American League. He felt that Angels GM Dick Walsh had “blackballed’ him. “Walsh didn’t try to trade me, and I wasn’t about to play for a man who didn’t think I still had ability.” He started working as a life insurance salesman, but then spent the next nine months working on a construction crew for $6.50 an hour, and one of the jobs involved helping build what became Kauffman Stadium.29 “I was a laborer pouring concrete, cleaning up lumber. It was rough, all that snow and cold and ice.”30 Years later, he recalled some of the work. “You know, when you watch on TV, you know that wall in the Royals bullpen? We poured that wall one day, and the next day it was sagging so we had to tear it down again.”31

Walsh was replaced by Harry Dalton as GM in October 1971. On January 29, 1972, the Angels announced that Azcue had signed a contract and would join the club for spring training as a non-roster player. “I may be in the best shape of my career,” he said. “Mentally, I have never felt better.”32 He acknowledged he was glad to be back in baseball, even if it might only be to work as a backup catcher. “I missed that (baseball) paycheck…a lot of players don’t realize what is going on in the outside world. I appreciate being a professional baseball player now.”33

He made the club, but only as a backup. He pinch-hit in two games, making outs both times, and filled in defensively for one inning in a third game, on May 12. Four days later, he was sent to Salt Lake City, where he hit .319 in 45 games, sufficient to attract the interest of the Milwaukee Brewers who traded Ron Clark and Paul Ratliff for him and Syd O’Brien on July 28. He was only used in 11 games, and was 2-for-14 at the plate without a run batted in.

On November 15, 1972, he was released by Milwaukee. Just a few weeks later, the Cleveland Indians hired him to become a player/coach for their Double-A Texas League affiliate, the San Antonio Brewers. He had a very good year, playing in 105 games and leading the team with a .312 batting average and placing second in RBIs with 63. He was even named to the league’s All-Star team as the DH.

For 1964, the Indians asked him to become manager of their Single-A team in the California League, the Reno Silver Sox. “I wasn’t cut out to be a manager,” he readily admits. “Phil Seghi knew me since I was 16. I told Phil, ‘I’m sorry.’”34 He resigned in June. He took up selling automobiles in Kansas City for a while, and then as a salesman for Johnson’s Wax. For a while, he had his own company, providing janitorial services. Then he settled into a job where he worked for almost 30 years as a quality control manager for Molle Automotive Group. “When the cars came in, I would check them in. Make sure the cars were clean, and all that stuff.” It wasn’t an easy job, but he never let it consume him. He persevered until he turned 70 years old.

Azcue hasn’t followed baseball much since he retired from playing ball. He says he’s maybe gone to five games since then — despite a dozen years in the game and having helped build the ballpark. He might watch a game for a couple of innings on television. “I’m not a fan.”35

The Azcues — Joe and Judy — have three daughters, seven grandchildren, and three great-grandchildren. Most remarkably, in this day and age, they all live within five blocks of each other, within a mile’s radius of the Azcues’ Shawnee Mission home, near Overland Park just southwest of Kansas City. “It takes me five minutes to go to each one.” In something of an understatement, he says, “We are kind of a close family.”36

Last revised: February 15, 2018

Sources

In addition to the sources noted in this biography, the author also accessed Azcue’s player file from the National Baseball Hall of Fame, the Encyclopedia of Minor League Baseball, Retrosheet.org, and Baseball-Reference.com.

Acknowledgments

This biography was reviewed by Norman Macht and fact-checked by Warren Corbett.

Notes

1 Earl Gustkey, “Azcue: From Cuba to the Big Leagues,” Los Angeles Times, August 11, 1970: E16C.

2 Author interview with Joe Azcue on January 26, 2018. In his professional career, he has always pronounced his name “Ahz-cue” rather than the Spanish “Ahz-coo-AY.” Jorge Azcue worked with his uncle in Puerto Rico, but then moved to Miami and started a very successful business rebuilding truck engines for American Airlines and other big customers.

3 Ross Newhan, “Azcue Banks on Bat to Win Back Angels Catching Job,” Los Angeles Times, May 25, 1972: E1.

4 Ron Rapoport, “Ex-Angel Azcue Still Bitter, Quits,” Los Angeles Times, April 15, 1971: D1.

5 “Palatka First-Half Champs,” The Sporting News, June 26, 1957: 41.

6 “Meet Four of Jersey’s Top Players,” Jersey Journal (Jersey City, New Jersey), July 12, 1960: 3.

7 Peter C. Bjarkman, A History of Cuban Baseball, 1864-2006 (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, 2007), 104. One contemporary news story regarding the International League departing from Cuba came from UPI. “International League Pulls Out of Havana,” Los Angeles Times, July 9, 1960: A5.

8 “Trumpeting Catcher,” Tacoma Daily Ledger, October 9, 1960: 31.

9 Jorge S. Figueredo, Cuban Baseball: A Statistical History, 1878-1961 (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, 2003), 476.

10 Earl Gustkey. They first settled in Kansas City, where Jose was at the time (and still remains.) His parents found the language barrier difficult, and Joaquin soon joined his own brother rebuilding engines in Puerto Rico. Joe volunteered that he wasn’t particularly close with his father, saying in the 2018 interview, “I was always a rebel.”

11 Author interview on January 26, 2018.

12 Hal Lebovitz, “Azcue Lets Hurlers Choose the Pitches,” Cleveland Plain Dealer, August 29, 1963: 53.

13 Author interview.

14 Author interview. Azcue added, “I don’t have nothing against the athletes of this generation but — goddamn — they’re like a piece of paper. They’d get a finger blister and say, ‘I can’t bat.’”

15 “Azcue Holds Lead,” Plain Dealer, February 21, 1964: 30.

16 Hal Lebovitz, “Joe Goes by Book — On Field or Off,” Plain Dealer, March 5, 1965: 37.

17 Ibid.

18 Earl Gustkey.

19 Author interview.

20 Jose (Joe) Azcue, “Azcue Touches Publicity Bases,” Plain Dealer, January 8, 1965: 29.

21 Russell Schneider, “Azcue Reduces, Does ‘Research’,” Plain Dealer, January 7, 1966: 29.

22 Russell Schneider, “Batting Around,” Plain Dealer, April 25, 1967: 34.

23 Russell Schneider, “Azcue Back in School,” Plain Dealer, March 7, 1967: 33, 36. He was charged with 17 passed balls in 1967, however, more than any other catcher.

24 Will McDonough, “Hawk Gives In, Goes to Cleveland,” Boston Globe, April 23, 1969: 1.

25 “Azcue Jumps Sox, Suspended,” Boston Herald, June 12, 1969: 39, 41.

26 UPI, “‘I’ll Quit Baseball’ — Azcue,” Boston Record American, June 15, 1969: 26.

27 Harold Kaese, “Sox Too Proud to Keep Azcue?” Boston Globe, June 19, 1969: 51.

28 Associated Press, “Angels Purchase Catcher Torborg,” The Advocate (Baton Rouge), March 15, 1971: 26.

29 Ross Newhan.

30 Associated Press, “Azcue’s Angels Job In Nowhere Near Concrete,” New Orleans Times-Picayune, April 18, 1972: 25.

31 Author interview.

32 Ibid.

33 Hy Zimmerman, “A Striking View of Baseball Pay,” Seattle Daily Times, March 28, 1972: 43.

34 Author interview.

35 Author interview. That said, he has maintained friendships from baseball days and had just spoken with Rocky Colavito the day before the January 2018 interview.

36 Author interview.

Full Name

Jose Joaquin Azcue Lopez

Born

August 18, 1939 at Cienfuegos, Cienfuegos (Cuba)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.