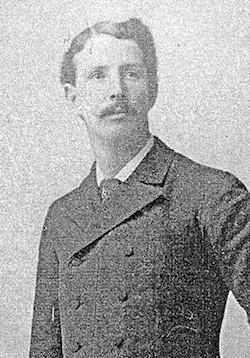

Bill McGunnigle

William “Gunner” McGunnigle had a flair for fashion on a baseball field that likely will never be matched. McGunnigle managed and coached the bases wearing black patent-leather shoes, a cutaway suit coat, lavender trousers, a silk tie and a derby hat. “It’s only a good looking man like yours truly who could wear patent leathers on the field and get away with it without getting shot at,” he once joked to a reporter.i

William “Gunner” McGunnigle had a flair for fashion on a baseball field that likely will never be matched. McGunnigle managed and coached the bases wearing black patent-leather shoes, a cutaway suit coat, lavender trousers, a silk tie and a derby hat. “It’s only a good looking man like yours truly who could wear patent leathers on the field and get away with it without getting shot at,” he once joked to a reporter.i

The legacy of pioneer baseball man Bill McGunnigle goes far beyond patent-leather shoes, however. As a player he was credited with inventing the catcher’s mitt in 1875. As skipper of the future Brooklyn Dodgers, he won Brooklyn’s first two pennants and remains the only manager in baseball history to win consecutive championships in two different major leagues. He has the highest winning percentage of any manager in Dodgers franchise history.

William Henry McGunnigle was born in Boston, the son of Irish immigrant parents, on New Year’s Day of 1855. When he was a boy, the family moved to nearby East Stoughton (now Avon), next to Brockton, then the shoemaking capital of the world. Billy’s father, James F. McGunnigle, became a Civil War hero as a twice-wounded Union officer. At the Battle of Spotsylvania Courthouse, a rebel bullet smashed into McGunnigle’s chest, but his life was saved when the bullet hit a hunting watch that he carried over his heart in his shirt pocket. The watch had been a gift from a friend back home.

After the war young Billy, who had inherited his father’s dashing good looks, began playing baseball on East Stoughton’s green fields. After the eighth grade, he dropped out of school and began working in a local shoe factory to help support the family, which now counted six children. On November 24, 1874, he married Mary McCullough, the pretty daughter of Irish immigrants. But Billy also had another love, the game of baseball, and it would change his life.

Billy was watching an 1873 game between teams from the towns of Brockton and Grafton when Brockton’s catcher was injured. Brockton’s captain, Owen Canary, asked if anyone in the crowd could catch. “A young fellow of eighteen came out of the woods with a gun on his shoulder and asked for a chance to catch the pitching of Joe Hallett, local twirler for the Brockton nine,” said Canary. “I gave it to him, and he made good.”ii Billy’s strong throwing arm earned him a new nickname: “Gunner.”

In 1874 Gunner led the Howard Juniors, an amateur team in Brockton, to the Junior Championship of Massachusetts. “He was delighted and inspired when he hit his first home run in Brockton, ran crazily around the bases and turned a somersault as he crossed home plate to win the game. He decided that baseball was the game for him,” one of McGunnigle’s sons, William, wrote in a letter to the Baseball Hall of Fame.iii

At this time, towns were starting to hire professionals to bolster their amateur teams. In June of 1875, the club in Fall River, Massachusetts, recruited McGunnigle to be the team’s first pro player. Though he was only 5-feet-9 inches tall and weighed just 155 pounds, young McGunnigle became the team’s starting catcher. In those days, catchers snared the pitcher’s underhand tosses without a glove or mask. As a result, a catcher’s hands took a severe beating.

When McGunnigle’s hands became very sore, the innovative young man decided to do something about it. Before a game with Harvard College, he borrowed a pair of thick bricklayer’s gloves. He tried them out during practice, but found they restricted his throwing. So he got out a jackknife and cut the fingers off the right-hand glove.iv The padded mitt “was an immediate success,” the New York Sun said, that “will save the broken fingers known until now.”v

Just who really invented what in the early days of baseball is often hard to pin down. But according to the 1895 Reach’s Official Baseball Guide, “The catcher’s mitt was first used in 1875 by William McGunnigle of the Fall River team.”vi

Before the 1876 season rolled around, young McGunnigle had more big ideas. The National League began that year. McGunnigle argued that “Fall River was just as ripe for pro ball as Boston” or any other big city.vii He persuaded the team’s owner to hire more professionals, and Fall River roared to the New England Association championship.

The speedy McGunnigle switched to the outfield, dazzling fans with spectacular barehanded catches. After a second-place finish in 1877, McGunnigle decided it was time to move on, much to the regret of local observers. “He is the greatest right fielder we ever saw,” said the Fall River Daily Herald.viii

In 1878 McGunnigle signed for a salary of $700 with Buffalo in the International Association. The team’s star player was a stocky, 22-year-old pitcher named Jim “Pud” Gavin. McGunnigle became Buffalo’s change pitcher – filling in for the few games Gavin didn’t pitch – and on other days played right field. Dashing Billy McGunnigle, now also known as “Mac,” quickly became a fan favorite. “This handsome young man has no superior in the country as a right fielder, prancing over his territory with a nervous energy which is destruction to everything sent his way,” the Buffalo Express said.ix

Mac’s specialty was charging like a shortstop to field a ball hit to right field and gunning the batter out at first base. “I have seen McGunnigle throw out as many as seven men in one game from right field to first base,” said Buffalo teammate Sam Crane. That season the New York Clipper newspaper awarded Mac its Clipper Prize as the league’s best right fielder, emphasizing his throwing 28 runners out at first, “his work in this respect being the best on record.”x He also hit .243 for the season.

After Buffalo won the International Association pennant, both the team and McGunnigle moved into the major leagues in 1879 when the club was accepted into the National League. During the season Mac was benched because of weak hitting. But when Galvin was injured, McGunnigle pitched two straight wins over the Chicago White Stockings (today’s Cubs), enabling Buffalo to edge Chicago for a respectable third-place finish. McGunnigle hit an anemic .170 for the season, but rolled up a pitching record of 9 wins and 5 losses with a 2.62 earned run average.

Over the winter McGunnigle and his wife, Mary, stayed in Buffalo while Gunner worked at Staley’s Shoe and Boot Store on Main Street. The McGunnigles’ second child, William, was born in Buffalo in 1880 and their third, Mary, arrived in 1882. Like their father, both children were born on New Year’s Day.

McGunnigle began the 1880 season as Buffalo’s captain and manager. He also became part of baseball’s first pitching rotation, with McGunnigle pitching one game and newcomer Tom Poorman hurling the next. The change was born out of necessity after Pud Galvin left to play in California. McGunnigle won his first game, but his arm went lame and he was released after only 17 contests. He played in only three more major-league games – one with the Worcester Ruby Legs in 1880 and a doubleheader with Cleveland in 1882. Gunner’s short big-league career ended with a .175 batting average, and a pitching record of 11 wins and 8 losses.

Mac eventually returned home to Brockton, where he worked as a cigar salesman as his arm healed. Then in 1883 he was recruited to captain a team in Saginaw, Michigan, in the new Northwestern League. His teammates included future Hall of Fame pitcher John Clarkson. Saginaw finished second to Toledo, which was led by African American catcher Moses “Fleet” Walker. But Saginaw was awarded the pennant when Toledo joined the major-league American Association in 1884. (When that happened, Walker became the first African American to play in the big leagues.)

Meantime, an expanded Northwestern League ran into financial trouble and began selling off its players. McGunnigle was sent to the league’s Bay City, Michigan, team, where he joined hard-hitting Jim “Cuddy” Cudworth, who would become his best friend. Then the Bay City team folded, and Mac ended up in Muskegon, Michigan.

McGunnigle returned to Brockton in 1885 to form a new team in the Eastern New England League. Now 30 years old and sporting long sideburns and a handlebar mustache, he was a confident and self-educated man. In private he was “a story teller in several dialects, had a good singing voice and a hearty appreciation of friendships. His family cherished him and his numerous friends took great delight in his company,” his son William later recalled.xi His pals included heavyweight boxing champion John L. Sullivan. Mac was a snappy dresser, preferring natty light trousers and cutaway jackets.

The new Brockton team was led by McGunnigle as playing manager and his Bay City buddy Jim Cudworth. About this time, all of baseball began allowing pitchers to throw overhand. But the pitcher’s box remained 50 feet from home plate, and hit batters didn’t get to take first base. Batters, as Mac discovered, were sitting ducks.

On July 22 in Brockton, McGunnigle stepped into the batter’s box to face pitcher Dick Conway of the Lawrence, Massachusetts, team. Mac dodged the first pitch, a fastball thrown squarely at his head. “The second was directly in the direction of the first, and the batter only saved himself by dropping suddenly on all fours to the ground,” the Brockton Weekly Gazette reported. When “a third ball sped from the pitcher’s hand like a bullet from a gun … the unfortunate batsman could not avoid the ball in time. And it struck him with a crash, which was heard in every part of the grounds. Poor ‘Mac’ fell like an animal beneath the butcher’s axe, and his quivering form was drawn up in agony as he lay upon the ground.”xii

McGunnigle was badly hurt, but returned to play that season. After he had recovered, the notorious incident eventually led to a family poem that Mac’s daughter Mary passed on to her children:

Casey on the pitcher’s mound

McGunnigle at the bat

Casey let the ball go

And knocked McGunnigle flat.xiii

McGunnigle led the Shoe City team to first place when the season ended in October – at least Brocktonites thought he did. Second-place Lawrence was allowed to play some postponed games and then won a three-game playoff with Brockton. Mac returned the next year, but the team played poorly. When the owners ordered McGunnigle to fine the players, he refused to do so and quit the team, leaving with Cudworth to play for the Haverhill, Massachusetts, squad.

Then in 1887, the New England League’s Lowell, Massachusetts, team hired McGunnigle as its player-manager. Led by McGunnigle’s underhand pitching and the hitting of Cudworth and future Hall of Famer Hugh Duffy, the Lowell Browns won the championship. Mac was a hero in Lowell but not in rival towns. One day while the team was on the road, he was getting a shave in a barbershop when the talk turned to the Lowell nine. “That darned McGunnigle,” the barber said. “If I had him here, I’d cut his big throat.” Mac chose to keep mum.xiv

Gunner’s triumphs gained wider attention. McGunnigle “as a manager, player and general on the field is head and shoulders above anything in the league and excelled by precious few in the country,” said Sporting Life. “In the minds of the baseball public,” the Boston Globe said, McGunnigle’s name “is a household word.” The pennant-winning manager caught the eye of Charley Byrne, president of the Brooklyn team in the American Association, who hired McGunnigle as Brooklyn’s new skipper for a pay of $2,500.

Byrne also was making other moves to strengthen the Brooklyn team, which had been perennial also-rans in the major-league American Association to the champion St. Louis Browns, led by player-manager Charles Comiskey. First Byrne and his partners purchased the entire New York Mets team and kept the best of the players. Then Byrne spent an unheard total of $19,000 to acquire three star players from St. Louis – pitcher “Parisian Bob” Caruthers, outfielder Dave Foutz, and catcher Doc Bushong.

Just before McGunnigle’s first season began in 1888, several of the Brooklyn players married, earning the team a new nickname: the Brooklyn Bridegrooms. The new team and manager made their Brooklyn debut on April 16, 1888, against Cleveland. McGunnigle was no longer a playing manager, and he didn’t wear a uniform. The natty, mustachioed Mac was attired in a dark suit, a bright tie, a shirt with a high white starched collar, a derby hat, and black patent leather shoes with removable spikes, a shoe that he had invented and patented. (Umpires and visiting players, who usually changed into their uniforms at hotels, could remove the spikes and avoid tearing the carpeting.)

Despite the star players, McGunnigle and the team struggled. In August, Mac seethed over press reports that he was merely an empty suit on the bench, and that club president Charley Byrne really ran the team. “I have seen it in print, and I understand that it started in the West, that I am only a figure-head in the Brooklyn Club, and simply carry out Mr. Byrne’s orders. This is false all the way through,” Mac told reporters.xv

According to Charles Ebbets, who was Brooklyn’s club secretary at the time, McGunnigle “was really the first manager Brooklyn ever had. Prior to that Mr. Byrne had been the actual manager although others had worn the title.”xvi

After Brooklyn closed the season by winning ten straight games to finish second to the St. Louis Browns, club president Byrne decided that McGunnigle deserved another chance. The Brooklyn players unanimously supported the decision, with many declaring that Mac was the best manager they had ever played for.

As an ever-optimistic Irishman, McGunnigle had no doubt about the 1889 baseball season. The Brooklyn manager vowed to “make a head long plunge from the top of one of the towers of the Brooklyn Bridge into the East River” if the Bridegrooms didn’t capture the pennant.xvii

After a slow start, Brooklyn jumped into first place in another close race with St. Louis. McGunnigle became known as the thinking man’s manager.

“Let me say a word of William McGunnigle, a man whose modesty tends to push his light under a bushel,” wrote one Sporting Life correspondent. “He does not court notoriety and always hugs the bench with his players. He is with his men at all times and on all occasions he is figuring at some method by which a profitable trick may be learned. Mac’s mind is ever on base ball, and you can seldom switch him off it, both in and out of school. The players think a heap of him, and the close attachment existing between he and they is evidenced in the fact that he is always a welcome guest to their circle.”xviii

Mac blew a tin whistle to get his players’ attention. He studied opposing catchers and managers. “McGunnigle was the first of the great sign stealers,” said Lee Allen, the former official historian of baseball at the National Baseball Hall of Fame. “He was also the first manager to signal to players by waving a scorecard on the bench. Nervous as a sitting hen, McGunnigle also gave signs by tapping bats, drumming away as if he were a telegrapher.”xix

It was later disclosed that the ever-inventive McGunnigle had some wild ideas that he wanted to try. One of his ideas “was what the boys called his electric heel tapper,” Sporting Life reported. Mac’s idea was to put a small metal plate in the batter’s box that would be wired to a button on the bench. McGunnigle would press the button to send shocks to his batters to signal what the pitcher was about to throw. He even called in an electrician to get a cost estimate, but dropped the idea when the electrician warned that the electrical current “might prove dangerous.”

Before long, the innovative manager had another idea. Brooklyn’s Washington Park had a big sign above the center-field fence. It was a cigarette advertisement with a huge picture of a dog’s head. McGunnigle wanted to paint one eye black and one eye white. “He proposed to manipulate the eyes by electricity, for, be it understood, Mac is an Edison in embryo,” Sporting Life said. “A straight ball coming he would let down the white eye. The black eye would indicate a curve ball.” His players kidded him out of that one.xx

Even without shocks or winks, manager McGunnigle led Brooklyn to its first major-league pennant in 1889, winning the American Association flag by one game over St. Louis. Brooklyn played its first “World’s Series” against the National League’s New York Giants, who were led by six future Hall of Famers including Buck Ewing, Tim Keefe and John Montgomery Ward. Brooklyn took a surprising three games to one lead before the Giants stormed back to take the Series, six games to three.

In the clubhouse after the Series, Brooklyn players showed their esteem for their manager by presenting him with a gold watch and chain and a diamond-studded locket. Perhaps recalling his father’s Civil War adventure, McGunnigle told the players: “Boys, you caught me unprepared. Of course, I can’t tell you how much I appreciate your kindness. I can assure you that whatever happens the watch will never visit ‘my uncle’; that it will be kept in a chamois case and that it will always be carried in a pocket over my heart.”xxi

In 1890 Brooklyn switched to the National League. That year McGunnigle and all of baseball got caught up in a storm. Many of the top players, led by Brotherhood president John Montgomery Ward, revolted and formed a third major league with teams in the very same cities as the National League. Almost all of Brooklyn’s players remained loyal to the club, and McGunnigle was able to lead the team to a second straight pennant, its first in the National League.

After spending a day on the bench in the final road series against Cleveland, when Brooklyn won all four games, a Sporting Life reporter wrote: “There isn’t a Brooklyn player who works harder to win a game than does Billy McGunnigle. He is here, there and everywhere sliding from one end of the bench to the other, always with a bat in his hand and one at his feet, and as nervous as a sweet girl graduate just before firing off her essay.”xxii

McGunnigle and Brooklyn also made history that year by playing in baseball’s first tripleheader in a September 1 clash with Pittsburgh. The Bridegrooms won all three games. There have been only three tripleheaders in the history of baseball, and McGunnigle was involved in two of them. He was the manager of the Louisville Colonels when they played the second tripleheader, on September 7, 1896, losing all three games to Baltimore. The third triple bill took place on October 2, 1920, when Cincinnati won two of three against Pittsburgh.

Few men in the history of baseball at the time could match McGunnigle’s winning record, Sporting Life noted: “A great deal has been said at odd times of various players and managers who have been connected in their time with many champion teams, but one man, with a more remarkable record than any of the others many mentioned, has been entirely overlooked, simply because he is altogether too modest for the pushing baseball world and never blows his own horn. That man is Manager McGunnigle of the Brooklyn Club. … Even [Cap] Anson doesn’t approach McGunnigle’s record of handling winning teams by a long shot. Nine firsts and three seconds in 14 years is simply phenomenal.”xxiii

Despite his success, McGunnigle became a victim of the fallout from the great baseball war. The Players League died after only one season, but the three-league competition had turned off fans and attendance plummeted. The surviving National League and American Association teams scrambled to woo investors from the former Players clubs. The Brooklyn Bridegrooms took on minority investors from the Players’ Brooklyn team, called Ward’s Wonders after its manager Johnny Ward. But as part of the deal, the Bridegrooms had to agree to make Ward the team’s manager. Bill McGunnigle was let go despite having won two straight pennants.

McGunnigle never spoke publicly about the dismissal, and the Brooklyn Eagle noted only that Mac “left this city with the best wishes of the men who employed him.” In his three years managing Brooklyn, McGunnigle won 267 games and lost 139 for a winning percentage of .658, still the highest in Dodgers franchise history.

There were hints that Mac left Brooklyn voluntarily so he could spend more time with his growing family in Brockton. Such speculation was undercut by the fact that in the middle of the 1891 season McGunnigle jumped at the chance to take over as manager of the last-place Pittsburgh team in the National League. But he got caught on the wrong side of an ownership dispute and was let go at the end of the season.

Still, McGunnigle left his mark. One of his players, catcher Connie Mack, noticed McGunnigle signaling with bats and scorecards. Mack later became manager of the Philadelphia Athletics for 50 years and was famed for signaling his players with a scorecard.

In 1892 McGunnigle returned home to manage another baseball team in Brockton. In July of that year, he helped baseball player Fred Doe organize the first professional Sunday baseball game ever played in New England, playing at Rocky Point Park in Rhode Island despite a state law barring baseball on the Sabbath.

Over the next few years, Mac became involved with polo and indoor baseball played on roller skates. His family had grown to seven children. He remained devoted to his wife, Mary. In 1895 he wrote about what makes a good marriage:

“Husband and Wife. Never should both be angry at the same time. Never deceive; confidence once lost, can never be wholly regained. Always leave home with a tender goodbye and a pleasant word, for they may be the last. Do not require a request to be repeated. Never reproach the other for an error which was done with good motive, and with the best judgment at the time. Never neglect the other for all that there is on earth. (I have done this) from Nov. 24, 1874 to this date.”xxiv

Mac returned to the National League in mid-1896 as manager of the last-place Louisville Colonels. During a stop in Washington, D.C., he took his players to the White House, saying he knew President Grover Cleveland. The players assumed it was another of Mac’s practical jokes. At the White House President Cleveland greeted McGunnigle, “Why, Mac, how are you? We haven’t met in years.” The president, who was from Buffalo, explained to the startled players that he had seen McGunnigle play there in the late 1870s.

McGunnigle made worldwide news by asking Cleveland if he planned to run for reelection. For the first time publicly, Cleveland said, “No third term for me. Really, I couldn’t stand it.”xxv

Despite a verbal two-year contract, Louisville fired McGunnigle after one season. He sued and won a small settlement out of court. McGunnigle’s five-year record as a major-league manager totaled 327 wins and 248 losses, for a winning percentage of .569.

Gunner returned to Brockton, where he opened a pub and poolroom downtown across from city hall. On the night of July 22, 1897, he was returning home with several others in a horse-drawn carrier that was struck by one of Brockton’s new electric trolley cars. Mac was thrown to the street and badly injured. Ironically, the man who once managed a team that became known as the Trolley Dodgers was done in by a trolley car.

McGunnigle never recovered his health and died on March 9, 1899, at the age of 44 at his home at 35 Arch Street. Among friends who attended his funeral were heavyweight boxing champions John L. Sullivan and Jim Corbett. McGunnigle, one obituary said, “seldom talked of his record and achievements, and the details of one of the most interesting careers in the baseball world passes with its subject.”xxvi

In 1915 prominent Boston Globe sportswriter Tom Murnane predicted that “some day there will be an institution to honor the pioneer heroes of the diamond and also the modern stars. When that day arrives, Billy McGunnigle, because of outstanding playing ability, sagacious leadership and aggressiveness, should be one of the first enshrined therein.”xxvii The National Baseball Hall of Fame opened in 1936 in Cooperstown, New York. In 1978 Murnane received the Hall’s J.G. Taylor Spink Award, conferred annually on a sportwriter.

Bill McGunnigle’s managing career didn’t last long enough for him to be considered for the Hall of Fame. However, there is a room at the Hall of Fame museum in Cooperstown devoted to baseball in the 19th century. Certainly, Gunner McGunnigle, the inventor of the catcher’s mitt and one of the most innovative baseball minds of the game’s early days, deserves a mention there.

Sources

Ronald G. Shafer, When the Dodgers Were Bridegrooms, Gunner McGunnigle and Brooklyn’s Back-to-Back Pennants of 1889 and 1890, (Jefferson, North Carolina: MacFarland and Company Inc., 2011).

Notes

i Washington Post, November 10, 1896.

ii Brockton Times, February 15, 1915.

iii Letter by son William McGunnigle to Baseball Hall of Fame, August 29, 1966.

iv New York Times, January 24, 1915.

v New York Sun, April 27, 1890.

vi 1895 Reach’s Official Baseball Guide.

vii Frank McGrath, Fall River Baseball History, 1839-1939 (booklet, no publisher listed, 1940).

viii Fall River Daily Herald, October 25, 1877.

ix Buffalo Express, August 13, 1879.

x New York Clipper, May 30, 1879.

xi Letter by son William McGunnigle, August 29, 1966.

xii Brockton Weekly Gazette, July 25, 1885.

xiii Letter by McGunnigle’s granddaughter, June 7, 1999, to McGunnigle’s great-great-granddaughter Monet Solberg.

xiv Robert A. Kane, “Billy McGunnigle,” Baseball Research Journal Volume 28 (Cleveland: SABR, 1999), 17.

Lee Allen, The Giants and the Dodgers (New York: Putnam, 1964), 25.

xv Sporting Life, August 15, 1889.

xvi Brooklyn Eagle, February 14, 1913.

xvii New York Clipper, April 6, 1889.

xviii Sporting Life, August 7, 1889.

xix Lee Allen, The Giants and the Dodgers, 25.

xx Sporting Life, July 18, 1891.

xxi New York Times, October 31, 1889.

xxii Sporting Life, October 4, 1890.

xxiii Sporting Life, October 4, 1890.

xxiv Brockton Enterprise, April 8, 1990.

xxv Los Angeles Times, June 15, 1896.

xxvi Brockton Times, March 10, 1899.

xxvii Brockton Times, February 15, 1915.

Full Name

William Henry McGunnigle

Born

January 1, 1855 at Boston, MA (USA)

Died

March 9, 1899 at Brockton, MA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.