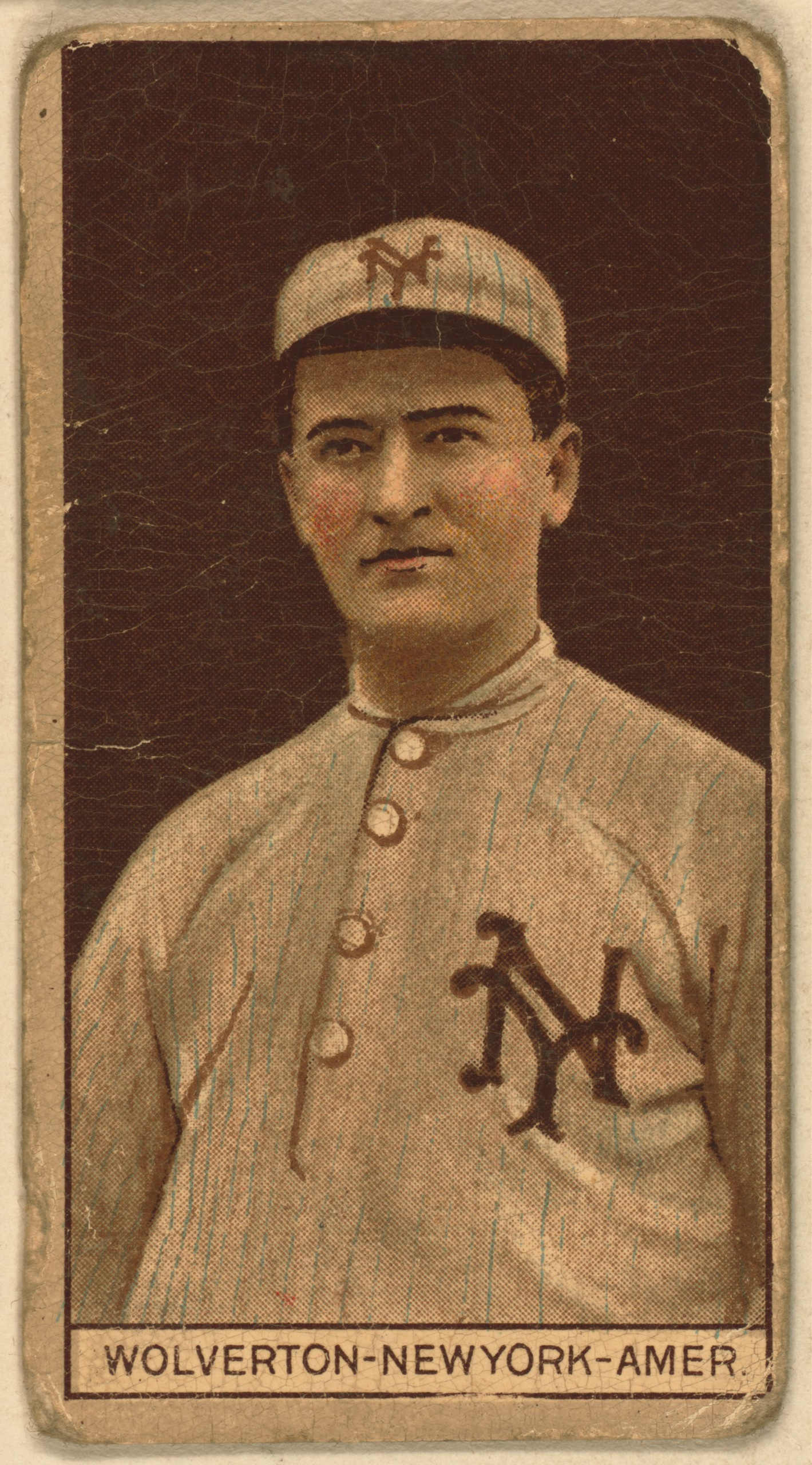

Harry Wolverton

On April 11, 1912, the New York American League club opened its season at Hilltop Park in New York City with a new official team nickname, the Yankees. For the first time in the club’s history, the players wore pinstriped home uniforms. The team also welcomed a new manager, Harry Wolverton. He preferred the team’s old name, the Highlanders. He often wore a sombrero with his pinstripes. And when club owner Frank Farrell presented Wolverton with a floral horseshoe display, everyone noticed that it was mounted upside down. Yes, the luck ran out. The Yankees lost to the Red Sox, 5-3. They continued to lose games – 102 in all – and finished the season in last place. Wolverton, who never believed in luck (good or bad), excuses, or apologies, offered no explanations on the dismal outcome to anyone including Yankee owners and fans. Always an optimist, he promised to win the pennant next season.

On April 11, 1912, the New York American League club opened its season at Hilltop Park in New York City with a new official team nickname, the Yankees. For the first time in the club’s history, the players wore pinstriped home uniforms. The team also welcomed a new manager, Harry Wolverton. He preferred the team’s old name, the Highlanders. He often wore a sombrero with his pinstripes. And when club owner Frank Farrell presented Wolverton with a floral horseshoe display, everyone noticed that it was mounted upside down. Yes, the luck ran out. The Yankees lost to the Red Sox, 5-3. They continued to lose games – 102 in all – and finished the season in last place. Wolverton, who never believed in luck (good or bad), excuses, or apologies, offered no explanations on the dismal outcome to anyone including Yankee owners and fans. Always an optimist, he promised to win the pennant next season.

John the Baptist Wolverton and Amanda Wolverton felt that same optimism when they welcomed their second son, Harry Sterling Wolverton, into the world on December 6, 1873, in Mount Vernon, Ohio. The blond-haired Sterl (his nickname growing up) found the ideal example of the hardworking family man in his father. A Civil War veteran, John married Amanda in 1868 and joined his father, Clement, in the steam dye business, in which he labored for the next forty years. His children had other dreams. The oldest child, Fred, born in 1871, became a successful dentist. A daughter, Birdie, born in 1878, married and moved to Florida. Sterl’s lifelong ambition was to play professional baseball. “As a boy on the Mt. Vernon sandlots, he lived baseball and was always playing or practicing some angle of the game,” reported his hometown newspaper, the Mount Vernon Republican, years later. According to local legend, Harry played baseball so much that after his friends grew tired, he paid other boys a nickel to continue playing with him. He was the captain of his high-school baseball team, but he gained legendary status as the boy who could hit baseballs father than anyone had ever seen.

Wolverton attended Kenyon College in nearby Gambier, Ohio. The small, all-male college was not known for its athletics. Except for a note in the student files listing him as a “special student” with a grade of 60 in a freshman English class, Wolverton made his mark on the football and baseball fields. The star athlete became regular copy in the campus newspaper, the Kenyon Collegian. Although he spent three seasons as a halfback on the football team and once ran a kickoff return for a 40-yard touchdown, his real passion remained baseball. After missing the opening game in 1894 because he flew over the steering wheel of his bicycle and hurt his shoulder, “Wolverton played his usual good game,” reported the Kenyon Collegian in May. The left-handed hitter proved ideal in the cleanup spot in the lineup and his defense at catcher caught everyone’s attention. “As usual Wolverton made some rather phenomenal stops behind the bat,” noted the campus paper the following April. “As usual Wolverton gave us another home run,” reported the Collegian in May 1895. His only shortcoming on the diamond was pitching. “He has not yet gained control of the ball,” the Collegian wrote.

Wolverton’s college career ended during his junior year when he and a few classmates decided to move an unacceptable freshman out of their dormitory. “We were elected to move one of the boys along in college,” Wolverton explained years later. After the freshman refused to leave, they decided to scare him away by means of a small improvised bomb made of twine, piping, and gunpowder. It worked better than anyone expected. The explosion tore apart their target’s room and a chunk of the building. No one was hurt, but the college administration began an investigation. Wolverton did not wait around for the results. Always looking to the positive side of any situation, he admitted that despite costing him an opportunity to gain a college degree, the episode pushed him into professional baseball.

Wolverton finished the summer of 1895 on the local Paulding, Ohio, team as a pitcher and first baseman for $60 a month. Although he preferred playing an infield position, he signed with Columbus of the Western League on February 22, 1896, as a pitcher. His lack of control limited his pitching to the bullpen. On May 10 against Indianapolis, he came in as a reliever and struck out two batters, but he also threw a wild pitch, hit a batter, and walked one. “Wolverton probably needs another year before he will be able to go in and take his turn,” reported Sporting Life on May 23, 1896. He took a few turns behind the plate and hit an impressive .385 in a limited number of plate appearances.

Although Wolverton agreed to another season with Columbus, the club farmed him out to the Dubuque, Iowa, team in the Western Association. His baseball career appeared in jeopardy after he hurt his pitching arm during a game against Rockford. A few weeks later the team needed someone to fill in at third base. Wolverton, despite his misgivings about his ability to throw the ball across the diamond to first base, agreed to try. Sure enough, during the game he had to make the long throw. Just as he threw the ball, he heard something snap in his right shoulder. His arm felt fine. Rather than return him to the mound, Dubuque kept him at third base. “I liked the game so well that I preferred some position where I could play every day,” Wolverton said years later. Now that he had it, the new third baseman had to prove he could play the hot corner every day.

As a regular player Wolverton led Dubuque with a .294 batting average and became the best third baseman in the Western Association. He was the captain of his team and a respected player among fans and sportswriters. On August 28, 1897, Sporting Life declared, “Third baseman Harry Wolverton of the Western Association, is declared to be a fast fielder and hard hitter.” The Dubuque Herald wrote, “Wolverton deserves a good deal of credit for his steady, day in and day out efforts to play winning ball.” The local newspaper also singled him out as one of the few players who did not have to be disciplined for drunkenness or other violations of misconduct.

In October Wolverton was back with Columbus. After a tight pennant race developed between the Eclipse club and the Bryce Nine in the Columbus League, Wolverton was sold to the Eclipse team for $5. Despite Wolverton’s help, Eclipse lost the pennant. After the season he returned to Dubuque, where the local newspaper helped his offseason job search by describing him as “an expert accountant and a thorough gentleman.”

After the death of his father in February 1898, Wolverton reconsidered his options. Grief-stricken, he considered staying out of baseball in the coming season. He also felt disappointed with the contract offered by Columbus. After all, he could provide a consistent defense; he knew how to play every position on the field. Columbus agreed and raised its offer. Once again he proved his value on the field. By July his batting average had soared to .400. He also showed his aggressive nature: When a base runner spiked him at third base, Wolverton broke his opponent’s nose.

On August 10, 1898, the Chicago Orphans (the future Cubs) of the National League purchased Wolverton’s contract but gave him permission to stay with Columbus until its season ended and then report to Chicago. The Chicago Daily Tribune introduced the late-season call-up as “a quiet player, not given to talk, but he goes about his business in a matter of fact way.” Wolverton made his major-league debut on September 25 with two base hits. In 13 games with the 1898 Orphans, he hit .327.

During spring training the following season, the Tribune criticized the “unsatisfactory” work of the entire club with one exception: “Wolverton at third is working in clean, fast style.” Most Chicago fans were surprised when manager Tom Burns made the rookie the starting third baseman and number three hitter in the lineup. On April 16, 1899, in Cincinnati, a large contingent of fans from Wolverton’s hometown of Mount Vernon presented him with a diamond stud and gold watch. They led a standing ovation in his honor.

But if there was an accident waiting to happen, Wolverton found it. On June 12, in a game against St. Louis, Wolverton and backup catcher Art Nichols both chased after a high fly ball in foul territory. The collision between the 5-foot-10, 175-pound catcher and the 5-foot-11, 205-pound third baseman sent Wolverton crashing into the opposition bench. Nichols walked off the field. Wolverton was carried off and rushed by ambulance to the hospital. He received treatment for a deep cut over his right eye, scratches on his face, a lump on his head, and pain in his groin.

Although Wolverton returned to the lineup on June 29 with two hits, three putouts, and four assists, he now had competition at third base. Bill Bradley was the better hitter. During an Eastern trip in July, manager Burns blamed Wolverton’s poor baserunning for the team’s losing more than a couple of games. Again, injuries interfered with Wolverton’s opportunities to prove himself invaluable to his team. On July 22 the Chicago Daily Tribune noted that he was suffering from an injured shoulder that affected his play at third base.

Despite the injuries, Wolverton felt that he had played well during his rookie season. He felt so optimistic about a long career as an Orphan that he moved his mother and siblings to Chicago. Then on April 28, 1900, he was sold to the Philadelphia Phillies. The family moved to Philadelphia.

Wolverton took his place at third base on a team that possessed three future Hall of Fame players on its roster, Nap Lajoie, Ed Delahanty, and Elmer Flick. While the Phillies finished in third place, Wolverton had a good season, hitting .282 with a career-high 58 runs batted in in 101 games, but it was not without injuries. On August 14, while running out a groundball, Wolverton spiked St. Louis first baseman Dan McGann on the foot. Furious, McGann turned around and fired the ball at Wolverton’s head. Harry staggered, then went fists first at McGann. Police officers broke up the fight. Wolverton denied the spiking, but he definitely had a headache. He suffered a second headache on September 5 when he leaned out of a Philadelphia rail car and smashed his head against a pole. He was hospitalized with a fractured skull. Somehow he managed to return to the Phillies’ lineup before the end of the 1900 season.

Injuries continued to follow him. In August 1901 Wolverton was hitting over .300 when he broke his collarbone in a collision with Boston first baseman Fred Tenney. While he recovered at home, rumors about his impending defection to the American League’s Washington club overshadowed his successful season (he hit .309 in 93 games). When asked by the press if he had signed a contract, Wolverton replied, “I defy you to prove it.” That was enough for the Phillies’ management. Team treasurer John Rogers suspended Wolverton and fined him $600, the amount of his salary from the time of his injury to the end of the season. “The majority of players are ungrateful, deceitful and liars and cannot be trusted for even their words,” Rogers said. Wolverton sued the Phillies and signed a two-year contract with Washington at $3,250 per year regardless of whether or not he played any games.

Wolverton soon regretted it, both on and off the field. As the 1902 season progressed, he failed to hit in the clutch and his errors in the field alienated fans. “He was clearly ill. And he showed little interest in his work—not that he did not want to play his best game, but he was simply unable to,” reported the Washington Post on July 20. Court rulings in Pennsylvania and Washington allowed him to play for Washington as long he never played baseball in Pennsylvania unless he took the field with the Phillies. After a week recuperating from malaria, Wolverton sent a telegram to Washington manager Tom Loftus explaining his intention to return to the Phillies. Loftus told the press, “It was a mistake to sign him in the first place.” Washington baseball fans agreed. In 59 games, Wolverton hit only .249 with 24 errors. He finished the season in Philadelphia and in 34 games with the Phillies the returning third baseman hit .294.

Wolverton’s 1903 season in Philadelphia proved that he had made the right decision to return. The veteran player hit .308 with a career high 12 triples in 123 games. Newspapers hailed him as one of the best third basemen in the National League but observed that his temper sometimes hindered his opportunities as he was thrown out of several games during the season. Still, fans and teammates enjoyed Wolverton’s aggressive style of play even though the Phillies stumbled to a seventh-place finish. He also married Philadelphia native Mary Maroney and felt secure that he would call Philadelphia home for many years.

After selling clothes at a department store in Philadelphia during the offseason, Wolverton returned to the Phillies in 1904 expecting to duplicate his numbers and good fortune. He played in 102 games and hit .266, but his season was riddled with injuries including a sprained ankle, a split finger, and a sprained leg. In December 1904 Philadelphia traded Wolverton to the Boston Beaneaters for pitcher Togie Pittinger. At odds over money, Wolverton refused to sign his contract with Boston and considered playing in the independent Tri-State League. He finally signed with Boston in early March. The press cheered Boston’s acquisition of the veteran third baseman. Despite his failing to get a hit in 28 plate appearances in six games against Brooklyn in April 1905, the Boston Daily Globe noted that “Harry Wolverton put up a superb game at third.” He played one of the best defensive games of his career when he handled ten chances at third base without an error in Boston’s 2-1 loss to New York in June 1905. Despite a tough season at the plate (he hit only .225), Wolverton hoped to remain a Beaneater. The feeling was not mutual; the Boston management spent the winter trying to get rid of the weak-hitting third baseman but no one made an offer. The 33-year-old veteran was released, but he was not finished with baseball.

Wolverton spent the next three seasons at Williamsport in the independent Tri-State League. He earned a reputation as the best fielding and hitting third baseman in the league. By the end of his first season, his teammates recognized his leadership skills and made him manager. He rewarded their confidence with a pennant in 1907, their first year in Organized Baseball. “Wolverton has given Williamsport the best baseball team it ever had,” praised the Williamsport Daily Gazette and Bulletin in December 1907. The Cincinnati Reds purchased Wolverton’s contract but now that he was married with an infant daughter and enjoying his role as a player-manager, he requested his release. He stayed in Williamsport for one more season.

In 1909 Wolverton agreed to play third base and manage the Newark club of the Eastern League. He had no idea he would have to manage his boss. That winter Joe McGinnity, the former star pitcher of the New York Giants, and an associate purchased the team. McGinnity announced that he would pitch regularly. Manager and pitcher/owner did not get along. When Wolverton tried to remove McGinnity from the mound during a game, the owner did not approve. Wolverton was demoted to team captain while McGinnity made himself manager.

After the season Wolverton purchased his release. He thought he would be hired to manage the Baltimore Orioles, but new owner Jack Dunn had other plans. Sporting Life promoted Wolverton as “a valuable man, who can play any position on a team.” He had several other offers, and hired on to manage Oakland in the Pacific Coast League, a club that lacked fan support and talent. But Wolverton put together a strong pitching staff, disciplined his players, and forced the team to play as a unit. Oakland surged into the heart of the pennant race. “It certainly pays to have a winning ball team,” noted Will Baradori in The Sporting News on June 23. Fans poured into the ballpark to cheer on their Oakland team, which wound up in second place. (At one point, with the turnstiles moving and profits surging – Wolverton claimed the team made $50,000 that year – he offered to buy the Oaks for $48,000, but the owners turned him down.)

The first Easterner to manage in the PCL gained the respect of fans and players and the ire of umpires around the circuit. He earned the nickname Fighting Harry. His heated debates with umpires became legendary over the years, but in 1910 one argument changed the rules. According to a PCL historian, Dick Dobbins, after umpire Eugene McGreevy threw Wolverton out of a game against Los Angeles for arguing a call, the manager forbade his players to take the field. Fans rioted when McGreevy declared Los Angeles the winner by forfeit. The league installed two umpires in every game thereafter to help call plays in the field.

Wolverton was one of the best managers in the minors. He inspired his young players and pushed them to hustle no matter what the scoreboard showed. He taught them that the team came before the individual by disciplining even star players at the cost of winning a game. Wolverton’s reputation as a club leader traveled farther than he expected. When Hal Chase resigned as manager of the Highlanders/Yankees after the 1911 season, Wolverton emerged as the top candidate for the job. He agreed to manage the Oaks again in 1912, but he told the press, “I realize that the management of the New York Americans is an opportunity of a lifetime.” Except for his lack of experience managing a major-league club, Wolverton had the résumé. “Wolverton knows how to lead a club, understands the business thoroughly and is a fine judge of talent,” team owner Frank Farrell said. Wolverton got the job. He was returning to the major leagues.

The 37-year-old Harry Wolverton who took over the Yankees in 1912 was a confident, cigar-smoking, sombrero-wearing father of three little girls. “They are a pretty good family,” he joked, “but there are no ballplayers among them.” He liked to give long dissertations to the press in which he referred to the Yankees by their former nickname the Highlanders and repeated his promises to win the pennant. “I am staking my reputation upon the success of the team,” he said. He blamed their dismal 1911 finish on “the lack of team play.” When asked if he would insert himself into the line up, he replied, “There’s no need of my going in there unless I can sting the ball.” Despite his seven years away from major-league pitching, Wolverton’s confidence in himself had not faded.

The rookie major-league manager felt optimistic as he took his team to Atlanta, Georgia, for spring training. Hal Chase, Birdie Cree, and Roy Hartzell had combined to drive in more than 200 runs and pitching ace Russ Ford had won 22 games the previous season. Unfortunately, Wolverton did not anticipate Georgia rain. The Yankees were rained out during most of their spring training. They spent a total of three days on the field. Spring training was a washout and so was the start of the Yankees’ season. They lost their first six games.

Every month the Yankees lost more games than they won. Injuries, illnesses, batting slumps, fielding errors, and just bad pitching forced Wolverton to change his lineup almost daily. The players who took the field led the league with 286 errors. They made 81 double plays (the fewest in franchise history). Losing became routine but the manager never felt defeated. He brought up rookie players and waited for the veterans to get healthy. He inserted himself into the lineup and proved that he could still “sting the ball” by hitting over .300. He also showed his players how to grind through injuries. On July 6, while playing third base, Wolverton caught a line drive with his face. Despite the bleeding gash, he finished the game.

One newspaper, making a bad pun, called the Yankees “the most Titanic failure of the 1912 season.” The team finished 55 games behind the American League pennant winner, the Boston Red Sox. “Wolverton probably did as well under the circumstances as anyone could have done in his place,” wrote E.D. Soden in Baseball Magazine. Wolverton made plans rather than excuses. He expected to win the pennant the next season with fresh talent and healthy veterans. He never felt that any of his decisions during the failed season warranted his resignation. “I have never quit on a job in my life, and I’m not going to on this one,” Wolverton told Farrell. “If you don’t want me, fire me.” Farrell did. The last place Yankees ended Wolverton’s opportunity of a lifetime.

Wolverton was not out of a job for long. “I accepted the management of the Sacramento club because I like the Coast, its climate, and its people,” he told the Oakland Tribune in December. Once again he rebuilt a California team and renewed fan interest, The Wolves, named after their leader, finished in second place. In November he purchased the Wolves with business partner Lloyd Jacobs for an estimated $20,000. His tenure as an owner did not last long. The team lost $24,000 from spring training through Opening Day. By the end of the season the Wolves were bankrupt. At least Wolverton could console himself with song and family. In the winter of 1914 Clay W. Chapman published his song “That Wolverton Rag” in honor of the Wolves and their manager. Hope was renewed in October, when the 41-year-old became the father of twin girls, expanding his family to five daughters.

In 1915 Wolverton returned to the dugout with the San Francisco Seals. They won the pennant but almost lost their manager after he was run over by his own car on June 10. As he cranked the engine, his car rolled over him and dragged him more than 200 feet. He suffered a broken collarbone and fractured ribs. He managed the team from his hospital bed by telephone and telegraph until he was able to return to the bench.

After a disappointing season in 1916, the Seals returned to first place in 1917, but Wolverton did not enjoy it for long. On June 17 he was fired. “To say that I was surprised is putting it mildly,” Wolverton said. Owner Henry Berry said they disagreed on team expenses. Wolverton believed in investing large sums of money on players, but he insisted that he was “the most economical of managers.” Fans and players wanted him back in the league while sportswriters suggested that he should manage the Detroit Tigers. But in mid-July Wolverton bought a small farm in San Mateo, next to San Francisco. The quiet country life agreed with the 42-year-old ex-player and manager. On October 11, 1917, Wolverton announced his retirement from professional baseball.

No one believed that Wolverton would stay retired from the game that he loved and which had been part of his professional life for more than 20 years. “Get old silver top Harry Wolverton back on the job, give him the key and a decent sized bankroll and what a difference there would be in Oakland wins, patronage and last but not least, gate receipts,” proclaimed the Oakland Tribune in February 1919. In October, Wolverton signed a 10-year contract. Unfortunately for local baseball fans, it was a lease on the Ornbaun Mineral Springs in Mendocino County, a resort he planned to operate. When he gave up his lease a year later, there were rumors that he would manage Detroit or return to the PCL. No offers were made. Of all the disappointments, the worst tragedy struck on April 28, 1920, when his 10-year-old daughter, Mary, died from an illness.

Everything in Wolverton’s life changed again in November 1922 when he returned to professional baseball. He signed a contract to manage the Seattle club in the Pacific Coast League. Despite five years away from the game, the 50-year-old felt healthy and confident. In December he told a sportswriter, “You know I feel younger every year.” He promised that Seattle would fight for the pennant “unless all of the players break their limbs.” Unfortunately, there were enough injuries to interfere with his plans. For Wolverton the highlight of the season was probably a dinner at the Palace Hotel in San Francisco in May in his honor. More than 600 people showed up.

On July 8, 1923, Wolverton resigned as manager. He wouldn’t say why, but it was known that he and the team’s new owners disagreed about money spent on acquiring new players. The optimistic Wolverton told the press that he hoped to be back in the Pacific Coast League soon. While he did some work as a scout for the San Francisco club in September, he was also seen back at work as the sales manager of a local automobile company. Five years later, he was still selling cars in San Francisco. No one mentioned him anymore for managing jobs.

By 1931 the aggressive ballplayer who was quick with his fists on the field gave way to Special Officer Harry S. Wolverton of the Oakland Police Department. No one mentioned him anymore in connection with baseball until January 1937, when he attended a local luncheon in honor of former baseball star Duffy Lewis. It was the last time Wolverton enjoyed the company of his former colleagues. On February 4, 1937, while walking his beat in downtown Oakland, he was the victim of two hit-and-run accidents in a single night. In the first accident, Wolverton suffered a head injury, but after getting his head bandaged, he continued his patrol. He should have gone home. Before the end of his shift, he was struck by another car and left to die on the street. Whether the second accident dealt the fatal blow or death came as a result of injuries caused by both accidents, nothing changed the fact that Harry Wolverton was dead at the age of 63.

The following night businesses along his beat in downtown Oakland dimmed their lights in honor of the policeman who worked hard to protect his community and in memory of the baseball manager who never gave up on his team. Wolverton was survived by his wife and daughters. He was buried at Cypress Lawn Memorial Park in Colma, California.

March 4, 2011

Sources

Special thanks to the Baseball Hall of Fame in Cooperstown, New York; Janet at the Public Library at Mount Vernon and Knox County, Ohio; Lynn Manner, manager of special collections, and Sam Harris, special collections assistant, at Kenyon College; Ruth Wilhelm, Putnam County District Library, and Dan O’Brien for their help in finding articles and information.

Droxie, John. Iron Man McGinnity: A Baseball Biography. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland, 2009.

Gallagher, Mark. The Yankee Encyclopedia . Champaign, Illinois: Sports Publishing, 2003.

Reisler, Jim. Before They Were the Bombers. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland, 2005.

Snyder, John. Cubs Journal: Year by Year and Day by Day with the Chicago Cubs. Cincinnati: Emmis Books, 2005

Westcott, Rich, and Frank Bilovsky. The New Phillies Encyclopedia. Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1993.

Atlanta Constitution, Baseball Magazine, Boston Daily Globe, Daily Gazette and Bulletin (Williamsport, Pennsylvania), Dubuque (Iowa) Daily Herald, Chicago Daily Tribune, Kenyon Collegian, Los Angeles Times, Nebraska State Journal (Lincoln), New Castle (Delaware) News, New York Times, Oakland Tribune, Ogden (Utah) Standard Examiner,Portland Oregonian, Philadelphia Inquirer, Salt Lake Tribune, Sporting Life, The Sporting News, Washington Post

http://www.kenyonhistory.net

http://oaklandoaks.tripod.com.

Full Name

Harry Sterling Wolverton

Born

December 6, 1873 at Mount Vernon, OH (USA)

Died

February 4, 1937 at Oakland, CA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.