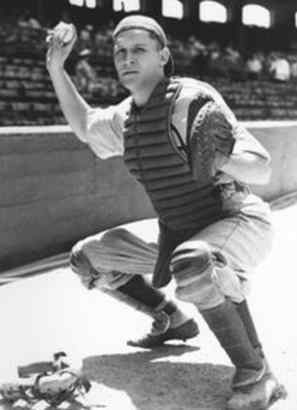

Harry O’Neill

Harry O’Neill played in just one major-league baseball game, had no times at bat, and no putouts or assists. Still, he won a measure of immortality as one of only two major leaguers who lost their lives during World War II. He was killed in action on March 6, 1945, during the battle for the Pacific island of Iwo Jima. His name is linked forever to that of Elmer Gedeon, an Army Air Forces pilot who was killed while flying a B-26 bomber over France on April 20, 1944.

Harry O’Neill played in just one major-league baseball game, had no times at bat, and no putouts or assists. Still, he won a measure of immortality as one of only two major leaguers who lost their lives during World War II. He was killed in action on March 6, 1945, during the battle for the Pacific island of Iwo Jima. His name is linked forever to that of Elmer Gedeon, an Army Air Forces pilot who was killed while flying a B-26 bomber over France on April 20, 1944.

Harry Mink O’Neill was born in Philadelphia on May 8, 1917, and was a standout athlete at Darby High School, progressing to Malvern Prep School before entering Gettysburg College in Gettysburg, Pennsylvania, where he majored in history. At Darby High, he played guard on the team that won the Kiwanis basketball tournament and was on the All-Kiwanis team selected by the Chester Times. He also was an all-county center on the football team.

O’Neill was a three-sport star at Gettysburg, playing center on the basketball and football teams, and helping the baseball team capture the 1938 Eastern Pennsylvania Intercollegiate baseball title as a catcher. Under coach Hen Bream, O’Neill’s solid play and sure-footed kicking helped the Gettysburg Bullets to the Eastern Pennsylvania Intercollegiate football championship later in 1938. “Harry O’Neill … gave the old grads high blood pressure when he calmly booted a 39-yard field goal on the last play before halftime,” wrote a local newspaper about Gettysburg’s 16-8 win over Franklin & Marshall in October 1938. Earlier in the month, on October 15, O’Neill had kicked the winning field goal in a game against Drexel.

O’Neill led the Gettysburg Bullets basketball team to championships in 1937 and 1938. “Harry O’Neill proved to be the spearhead of the Orange and Blue offensive throughout the year,” noted the 1939 Gettysburg College yearbook. “The lanky Bullet center set the season scoring mark at twenty points in one game and captured third place among the individual players of the East Penn circuit.” The Bullets website says of Harry, “As a basketball player, he could shoot and play defense well. He was the leading scorer throughout his three years, using those points to post last second wins over Ursinus and Navy.”

In baseball, he helped coach Ira Plank (brother of former major leaguer Eddie Plank) capture the 1938 Eastern Pennsylvania Intercollegiate baseball title, defeating Penn State. “Porky O’Neill reached the status of a hero here today,” said a local paper on May 4, 1938, “when his single in the ninth inning drove one run home and enabled the Gettysburg Bullets to nose out a stubborn Nittany Lion in nine grueling innings 5-4.”

Harry’s father, Alexander O’Neill, was an engineer, himself born to native Pennsylvanians, and listed in the 1920 Census as working in the chemicals industry. He was 40 at the time, married to 35-year-old Susanna Cassidy, an Irish immigrant. Susanna was a homemaker, and her Irish parents, James and Grace Cassidy, lived with the family at 120 South 29th Street in Philadelphia in 1910. James worked as a blacksmith. Neither Cassidy is found in Pennsylvania in 1920. Harry (his given name) had a brother who was 10 years older, William J. O’Neill.

As for Harry, the right-handed youngster had become a much sought-after athlete, and rumors that he would sign with the Washington Senators were commonplace in early 1939. Instead, O’Neill signed with Connie Mack’s Philadelphia Athletics immediately after his graduation on June 5, 1939, for $200 a month. He spent the rest of the year with Philadelphia as the third-string catcher, largely working in the bullpen.

O’Neill made his only major-league appearance on July 23, 1939, as a late-inning defensive replacement for Frankie Hayes against the Tigers. It was a blowout of a ballgame, with the Tigers leading 9-1 after three innings and 15-3 through seven. Hayes was 0-for-4 in the game, and finally Athletics manager Earle Mack – who had taken over from his father, Connie Mack, in late June when Connie became ill – decided to give Hayes the rest of the day off and put in O’Neill behind the plate. O’Neill never got a time at bat, and was not involved in any fielding plays. He caught the fifth of Philadelphia’s five pitchers, Chubby Dean. Dean walked two and struck out none, but didn’t give up a hit.

Also debuting in the same game was right-hander Gerard “Jim” Schelle from Villanova, another 22-year-old who’d been signed by the Athletics on June 14. A photograph in the July 3, 1939, Washington Post shows both Schelle and O’Neill with acting manager Mack and an outfielder just up from Duke, All-American halfback and punter Eric Tipton. Tipton had debuted on June 9 and appeared in 47 games that year, and 501 (batting .270) in his major-league career.

Schelle was the third of the five pitchers, and never recorded an out. He faced five batters and walked three of them, hit Rudy York, and gave up a single. He was charged with three earned runs. That was his major-league debut. It was also his last game, and he remains in the record books with an earned-run average of infinity. Schelle, lived until 1990.

Both rookies were large for the day – Schelle was 6-feet-3 and weighed 204 pounds. O’Neill was also 6-feet-3 and weighed one pound more, at 205.

The final score was 16-3, Tigers. Mack never used either Schelle or O’Neill again in a major-league game – but both appeared the very next day, July 24, in Cooperstown during an exhibition game played against the Penn Athletic Club on Connie Mack Day in Cooperstown, in celebration of baseball’s nominal centennial. The Athletics won, 12-6. And both played in another exhibition game on July 31, losing in a 6-2 defeat at the hands of one of their farm teams, the Federalsburg Athletics. The game was in Federalsburg, and the farm team was “augmented by the leading sluggers culled from all teams in the Eastern Shore League.” [Washington Post, August 1, 1939] Schelle himself was placed with the Federalsburg team at the end of their season, but no records of game participation survive. In 1940, he played in the Michigan State League (Class C) for the Flint Gems and the Saginaw Athletics. He was a combined 12-6 with a 3.72 ERA. Saginaw became a Chicago affiliate in 1941 and Schelle was 8-14 (4.79) with the Saginaw White Sox.

Harry O’Neill was released by the Athletics in September 1939. He joined the faculty of Upper Darby Junior High School as a history teacher and three-sport coach. The all-around athlete did not end his playing days on the sports field at that point. Interwoven with his teaching career and scholastic coaching assignment, O’Neill played semipro basketball with the Harrisburg Caissons of the Tri-County League during the winter of 1939-1940, and was back with the team as player-manager for the 1940-1941 campaign. He was also playing football with Clifton Heights of the Eastern Pennsylvania Conference in 1941, and made a benefit game appearance with the Delco All-Stars in October of that year.

O’Neill’s last time in organized baseball came in the summer of 1940. When the school year concluded in June, the 23-year-old made a brief return to the professional game, signing with the Allentown Wings of the Class B Interstate League. He doesn’t appear to have played for Allentown, and the Wings released him to the Harrisburg Senators of the same league the following month. He played 16 games for the Senators, accumulating 42 at-bats and batting .238 with one double and one home run. Harrisburg released him after the season ended in September. For the next 24 months, Harry was out of organized baseball.

At the beginning of September 1942, O’Neill enlisted in the United States Marine Corps and attended the Marine Officers’ Training School at Quantico, Virginia, graduating as a second lieutenant. He was assigned to the newly-formed 4th Marine Division and began a period of intensive training at Camp Pendleton, California.

Serving with the 4th Marines, he was promoted to first lieutenant at Camp Pendleton shortly before being shipped out to the Pacific in January 1944, where he made amphibious assaults at Kwajalein, Saipan, and Tinian. Philadelphia Inquirer writer Frank Fitzpatrick says that O’Neill was wounded at Saipan early in July – hit by shrapnel, for which he received the Purple Heart. He was treated at a naval hospital in San Francisco, and returned to active duty in October.

By February 1945, O’Neill was on his way to Iwo Jima to help secure the island for use as a base for long-range fighters to escort bombers on their missions to Japan. It was the fourth assault in 14 months for the 25th Marine Regiment, Harry’s outfit, and they were assigned to take and hold the beachhead’s right flank.

Iwo Jima, 750 miles south of Tokyo, is the middle island of the three tiny specks of the Volcano Islands. Five miles long, with Mount Suribachi at the southern tip, the island is honeycombed with ground-down volcanic vents. Hundreds of natural caves communicate with deep sulphur-exuding tunnels. Steep and broken gulleys cut across the surface, ragged sea cliffs surround it. Only to the south is there level sand, but it is fine, shifting, black pumice dust making the beaches like quicksand and rendering it impossible to dig a foxhole when in need of cover.

The island was riddled with pillboxes, gun pits, trenches, and mortar sites, and a three-day naval bombardment beginning on February 16 was intended to rid the island of much of its defense. But despite its magnitude, the bombardment had minimal effect and US forces met fanatical resistance when they hit the beaches on February 19. By the end of the first day, however, the 3rd, 4th, and 5th Marine Divisions had landed 30,000 troops on the island; the Seabees suffered greatly in the early going as they tried to facilitate landing for the Marines. On February 23, the Marines reached the top of Mount Suribachi.

March 6, 1945, was D-Day plus 15, the day that the first P-51 Mustang fighters (15th Fighter Group, US Army Air Force) landed to begin to provide support to the Marines. It had been slow going as American troops fought day by day, often gaining few yards even after a full day of fighting. The 5th Marines attacked the Japanese lines from the west at 8 A.M. and the 4th Marines attacked from the east at 9. By the end of the day, American forces had gained 200 more yards, and 1st Lieutenant Harry O’Neill had been killed in action, reportedly hit by sniper fire. It was three days later that US forces finally succeeded in splitting the Japanese force in two. The day after that, March 10, the 4th Marines reached the east coast. On the 14th, the Marines began to prepare for departure from Iwo Jima. March 16 saw the last resistance in the area controlled by the 4th Division.

It was a month before O’Neill’s wife, Ethel McKay O’Neill, received news of his death from the Navy Department.

“We are trying to keep our courage up, as Harry would want us to do,” wrote his mother, Susanna, in a heartfelt letter to Gettysburg College shortly after his death. “But our hearts are very sad and as the days go on it seems to be getting worse. Harry was always so full of life, that it seems hard to think he is gone.”

O’Neill was initially buried at the Iwo Jima Cemetery. His remains were returned to the United States in July 1947, and he is one of 17 former major-league ballplayers buried at Arlington Cemetery in Drexel Hill, Pennsylvania, in the cemetery’s Sunnyside section. Others buried in Drexel Hill include Jack Clements and Sherry Magee.

Fourth Marine losses were substantial. Seventy-eight officers and 1,384 enlisted men were killed in action on Iwo Jima (another 14 officers and 330 enlisted men died of their wounds), for a total of 1,806 fatalities. More than 7,200 men were wounded. The official total of 9,098 casualties represented nearly 50 percent of the division’s strength. In a personal account of his time on Iwo Jima, Al Perry of the 24th Marines wrote, “The Fourth Division left the United States in December of 1943 with 19,446 men and returned to the US in the middle of 1945 having experienced over 17,000 casualties.”

Perhaps of some consolation to the O’Neill family, taking Iwo Jima proved the prize worth fighting for. On March 4, O’Neill might well have heard the first damaged B-29 bomber struggle back from a raid on over Tokyo and land safely on Airfield No. 1. The plane’s pilot, Lt. Fred Malo, and his 10-man crew were glad to have landed, but the field was by no means fully secure, and the aircraft was under sniper fire for the half-hour it took to effect emergency repairs and enable it to resume its flight back to Tinian.

A 4th Marine Division history says that after securing the island, “Within a few months, the Army announced that 1,449 Superforts (B-29s), with crews totaling 15,938 men, had used Iwo as an emergency landing field.” It was a vital element in the ability to launch the aerial bombardment of Japan that had been intended.

Many of the hundreds of professional ballplayers who served in World War II devoted time to physical education, training, and morale-building work such as playing for service teams in the Army and Navy. It may sound cold-hearted, but Simon Kuper, writing in the Financial Times on May 6, 2005, presented a bit of reality: “The reason Gedeon and O’Neill were killed is that they were barely major leaguers at all. Gedeon’s big-league career had spanned one week in 1939, while O’Neill’s lasted just a game, in which he didn’t bat. These men ended up in combat because nobody wanted to watch them play Army ball. Only after their deaths did baseball claim them.”

Baseball does claim them, however, and there is something to be said for that.

In 1980, Harry O’Neill was inducted in the Hall of Athletic Honor at Gettysburg College for baseball, football, and basketball.

Sources

Much of the material comes from the www.baseballinwartime.com website. We have supplemented with research from sources cited in the text, as well as the online SABR Encyclopedia, retrosheet.org, and Baseball-Reference.com.

Alexander, Col. Joseph H. “Closing In: Marines in the Seizure of Iwo Jima” at http://www.ibiblio.org/hyperwar/USMC/USMC-C-Iwo/index.html

Fourth Marine Division website: http://www.fightingfourth.com/Iwo.htm

Gettysburg College Bullets website: http://www.gettysburgsports.com/hof.aspx?hid=127

Henry T. Bream Collection, Gettysburg College

Perry, Al. “A Personal History of the Fourth Marine Division in WWII,” at http://mysite.verizon.net/res71z3x/index.html

Full Name

Harry Mink O'Neill

Born

May 8, 1917 at Philadelphia, PA (USA)

Died

March 6, 1945 at Iwo Jima, (Japan)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.