Dusty Rhodes

Four swings made Dusty Rhodes famous. The pinch-hitting hero of the 1954 World Series, when the underdog New York Giants swept the Cleveland Indians, Rhodes delivered key hits in three of the four victories. And he never had to pay for another drink in New York.

Four swings made Dusty Rhodes famous. The pinch-hitting hero of the 1954 World Series, when the underdog New York Giants swept the Cleveland Indians, Rhodes delivered key hits in three of the four victories. And he never had to pay for another drink in New York.

“You know what Rhodes was?” his manager, Leo Durocher, asked years later. “He was a buffoon, and I say that affectionately. I loved having him on my ball club because of his personality and the funny things he did that kept everybody loose. But I couldn’t have stood two of him.”1

Rhodes played up his image as a country boy come to the big city and went along with stories about his drinking and carousing, up to a point. He maintained that Durocher exaggerated his after-hours adventures for their entertainment value. His major league career lasted just seven years. He never won a regular job because, according to Durocher, you could count on him to butcher at least one fly ball in the outfield every game.

“I ain’t much of a fielder and I got a lousy arm,” Rhodes said, “but I sure do love to whack at that ball.”2 For a single triumphant season, he was a devastating hitter, and for three autumn days Dusty Rhodes was king of the baseball world.

James Lamar Rhodes was born in Mathews, Alabama, near Montgomery, on May 13, 1927, one of eight children of Walter C. Rhodes, a farmer, and the former Annie Cawthon. The only thing certain about his childhood is that the family was poor. A Montgomery grocer, Fred Noland, took the boy in and gave him a job when he was about 15. Jim cited Noland as a major influence in his life. He joined the navy shortly after his 17th birthday and saw action in the Pacific in the final year of World War II.

After his discharge in 1946, he played semipro ball around Montgomery, where he met and married Mae Ellen Childers. A scout for the Southern Association Nashville Vols, Bruce Hayes, first spotted him when he hit a home run barefooted. Jim hadn’t planned to play that day and left his spikes at home. Since he was under-age, one of his friends signed his mother’s name on the contract Hayes offered. Hayes gave him the nickname “Dusty” because all ballplayers named Rhodes were called Dusty.3 Two others were playing in the minors at the same time.

A 6-foot, 175-pound left-handed hitter, Rhodes began his professional career in 1947 at Hopkinsville, Kentucky, in Class-D ball. The Chicago Cubs bought his contract, and he spent five full years in the minors, burdened by a reputation as a party animal. At Class-A Des Moines in 1950 he was labeled “a 12 o’clock guy in a 9 o’clock town.” Manager Charlie Root warned that he was drinking too much. “I cut down 50 percent,” Rhodes said. “I stopped drinking chasers.”4

Rhodes’s next stop was Class-B Rock Hill, South Carolina, where he liked the people and the fishing well enough to make it his offseason home. In 1951 he tore up the Tri-State League with 31 homers and a .344 batting average, but the Cubs sold him to Nashville after the season. His hot hitting continued in Double A in 1952, with 18 home runs and a .347 average before the Giants bought his contract in July.

The Giants were fresh from “The Miracle of Coogan’s Bluff” that brought them the 1951 National League pennant, but their outfield was a mess. Center fielder Willie Mays had been drafted into the army, and left fielder Monte Irvin broke an ankle in spring training. By midseason the Giants had fallen 5½ games behind first-place Brooklyn. Rhodes arrived just in time to hear a clubhouse tirade by manager Durocher.

Durocher put the 25-year-old into the lineup in left field. Rhodes responded with eight hits in his first five games on a road trip, then went home to the Polo Grounds, where the short right-field wall was an invitation for his left-handed swing. He slammed eight homers in his first 11 games in front of New York fans.

Rhodes instantly became a fan favorite. He ran full-tilt to first base on routine ground balls, and once scored the winning run against the Dodgers by dashing home from second on a high bouncer off the plate that was fielded by the pitcher.5 Although his bat cooled, he finished with an .817 OPS, but committed nine errors in just 56 outfield games. The Sporting News chose him for its rookie all-star team.

Irvin recovered in 1953 to reclaim left field, relegating Rhodes to pinch-hitting. He was not much good, going 6-for-39 (.154) in his first two seasons. He went into the lineup in August when Irvin injured a foot, and got hot. On August 26 he hit three consecutive home runs in one game against the Cardinals, two of them off left-handed pitchers. In 29 games as Irvin’s replacement, he racked up a .924 OPS.

After the season the Giants took off for a barnstorming tour of Japan. Rhodes was the hitting sensation on the trip, but it wasn’t his bat that saved his job. No matter what he did against Japanese competition, Durocher was determined to get rid of the defensively suspect, bourbon-swilling outfielder. The manager had run into Rhodes in the Tokyo hotel lobby one morning, “just barely able to stand” after a hard night. Rhodes explained that he had been visiting his sister.

Durocher went to owner Horace Stoneham’s room to demand that Rhodes be traded. When he knocked, Rhodes opened the door and invited Durocher to join him and the boss for a drink. Stoneham, a notorious drunk, wouldn’t part with a player who would hoist a few with him. (Rhodes had been visiting his sister; she was married to a navy man stationed in Japan.)6

Willie Mays came back from the army in 1954. After a quiet first month, he began to hit like Willie Mays. By July 4 he was batting .327 with 25 homers, and the Giants stood atop the standings, four games ahead of Brooklyn.

Rhodes, stuck on the bench, became Durocher’s go-to pinch-hitter. On the Fourth of July he was hitting .423 with 11 pinch-hits in 23 at-bats. He said he had changed his approach during the Japan trip. He had been a dead pull hitter — opponents sometimes put on the Ted Williams shift against him — but he learned from teammate Don Mueller, who sprayed singles all over the field. “Last year I went for the homers,” Rhodes said. “That means strikeouts, too, and nobody wants a pinch-hitter who fans.”7

The more he hit, the more his confidence grew. “I’ve been around a lot of ball clubs for a lot of years,” Durocher said, “and usually when you look down the bench for a pinch-hitter, most of the guys are trying to hide behind each other. Oh, they’ll pinch hit if you ask them, but for most of them it’s the worst kind of pressure. But Dusty was different. He’d anticipate the situation every time, and when you turned to look for him, he’d already have a bat in one hand and he’d point to his chest, like he didn’t even want you to even think of anyone else.”8

Rhodes finally got into the lineup on July 4 and homered in each of his first two starts. He went into a left-field platoon with the slumping Irvin. On July 28 he homered three times in one game, again off the Cardinals. A month later he tortured the Cardinals yet again with two home runs, two triples, and two doubles in a doubleheader. The next day St. Louis manager Eddie Stanky intentionally walked Hank Thompson to pitch to Rhodes. The Cardinal killer delivered a two-run single. When he reached first base, he tipped his cap to Stanky.

The Giants had taken over first place in June and held it until the end, finishing 97-57. Durocher always called the 1954 club his favorite of all those he managed, but he didn’t think he had a chance in the World Series. The Cleveland Indians had won an American League-record 111 games and knocked off the Yankees, winners of five straight Series. Cleveland’s Big Three starting pitchers —Mike Garcia, Bob Lemon, and Early Wynn — ranked first, third, and fourth in ERA.

Game One went into extra innings tied, 2-2. Mays kept it that way with The Catch, his over-the-shoulder grab of Vic Wertz’s towering drive in the 8th. “When Willie made that catch, it seemed like they died,” Rhodes remembered.9 But he was the one who nailed the coffin shut.

Lemon, the Indians’ starter, still looked strong when he opened the bottom of the 10th with a strikeout. Then he walked Mays, and after Willie stole second, Lemon intentionally passed Hank Thompson. Durocher played the platoon advantage, sending Rhodes up to hit for Irvin.

“Lemon had a sinker that would sink a foot,” Rhodes said later.10 But the first pitch he saw was a hanging curve. He popped it up. The wind took over, and the ball barely cleared the Polo Grounds’ 257-foot right-field wall for a game-winning three-run homer. Lemon flung his glove in frustration. “Lemon’s glove went further than my home run.”11 A cheap homer, an out in any other ballpark. “A home run’s a home run,” Dusty the philosopher said.12

The next day Cleveland’s leadoff batter, Al Smith, opened the second game with a homer off New York’s ace, Johnny Antonelli. Early Wynn retired the first 12 Giants before Mays walked to lead off the fifth. Thompson followed with a single. With two on and none out, Durocher, a dedicated hunch player, called on Rhodes to hit for Irvin again.

Wynn, living up to his reputation, knocked the pinch-hitter down with his first pitch. The count ran to a ball and two strikes, and then Rhodes dinked a blooper off the end of his bat that died in short center field, a single to chase home the tying run. Moments later the Giants took a 2-1 lead.

Rhodes stayed in the game in left field, and came up in the bottom of the 7th. Wynn knocked him down again. Wynn threw a knuckleball that didn’t dance, and Rhodes launched a line drive that was still rising when it banged into the façade of the right-field roof to seal a 3-1 victory. In the clubhouse after the game, drink in hand, he taunted the Cleveland writers: “I guess that was a cheap one, too?”13

The Series moved to Cleveland’s cavernous Municipal Stadium for Game Three. The Giants took a 1-0 lead against the third of the Indians’ aces, Mike Garcia. When they loaded the bases with one out in the third inning, Durocher went for the kill. Rhodes batted for Irvin. He cracked a sharp single to right to knock in two runs. It was his fourth consecutive hit, and he was batting 1.000 with seven RBIs.

The Indians had seen enough; Rhodes drew an intentional walk in the fifth. Cleveland’s Ray Narleski ended the magic by striking him out in the seventh, and Don Mossi fanned him in the ninth. The Giants won, 6-2.

Rhodes did not play in Game Four as New York completed the sweep. “It was just as well,” he quipped. “After the third game I was drinking to everybody’s health so much that I just about ruined mine.”14 Decades later he set the record straight. “I didn’t take one lousy drink during that World Series,” he emphatically told an interviewer.15

To go with his .667 batting average in the Series, Rhodes hit .341 during the regular season with 15 home runs and 50 RBIs in just 164 at-bats. He was 15-for-46 (.326) as a pinch-hitter. “He thought he was the greatest hitter in the whole world,” Durocher said, “and for that one year I never saw a better one.”16 Monte Irvin, a future Hall of Famer, insisted he didn’t mind being lifted for a pinch-hitter three times: “Under other circumstances, I probably would have been [mad], but Dusty was the greatest natural hitter I ever saw.”17

Just as unlikely as Rhodes’s World Series heroics was the white Alabaman’s friendship with his black teammates. His locker sat between Irvin’s and Thompson’s. “He was like a brother to all the black players,” Irvin said later, and Rhodes described Irvin as “one of the nicest persons I ever met in my life.”18 Mays also called him a brother.19

The World Series hero basked in the cheers of his two hometowns, Rock Hill and Montgomery. One Rock Hill resident said Rhodes’s parade was “even bigger than when Santa Claus comes.”20 A Montgomery businessman sent a private plane to pick up Rhodes, his wife, and sons Dusty Jr., 6, and Ronnie, 4. At the Montgomery celebration he was presented with a new red Mercury. A local wine company hired him as a goodwill representative, and he moved his family back to Alabama.

Three weeks later Rhodes flipped his new car and wound up in a hospital with bruised ribs. A preacher cautioned him that alcohol and gasoline don’t mix. “Hell, Reverend,” he replied, “I don’t drink gasoline.” At least, that’s the way he told it.21

A winter of wining and dining didn’t hurt Rhodes’s batting eye. In 1955 he hit .305/.389/.449 in 217 plate appearances as a pinch-hitter and occasional left fielder. But his average fell to .217 in 1956 and .205 the following year. He didn’t get along with Bill Rigney, who had replaced Durocher as manager: “I was Durocher’s boy as far as he was concerned.”22 Dusty and Mae divorced, and he remarried in January 1958 to Mildred “Mimi” DeFoise of Brooklyn. They had a son, Jeffrey, and a daughter, Helene.

The Giants moved to San Francisco in 1958, but Rhodes didn’t make the trip. The club’s farm system harvested a trio of young outfielders: Willie Kirkland, Leon Wagner, and Felipe Alou. The 31-year-old Rhodes was cut during spring training, optioned to Triple-A Phoenix.

Even a demotion couldn’t bring him down. “I loved it there,” he said.23 The perks included three road trips to Hawaii. Rhodes hit 25 homers and tied for the Pacific Coast League lead with 100 RBIs.

That won him a return to the majors in 1959. Used exclusively as a pinch-hitter, he went 9-for-48 (.188) and struck out in his last big league at-bat on September 27. After two more years in Triple A, he retired at 35.

Rhodes was adrift for the first few years after baseball. “It was a little hard to give it up,” he said, “and when the sun comes up in the spring and you’re not playing baseball you’re kind of lost.”24 He worked as a bartender in an Arizona resort, then returned to New York, where everybody knew his name. After a stint as a Pinkerton guard at the 1964 World’s Fair, he found his niche as a crewman on harbor tugboats. Eventually he became a captain and worked on the boats for more than 20 years. According to one account, he made more money in a month than he’d made in any year playing ball.25

When the American League adopted the designated hitter in 1973, sportswriter Wells Twombly said the job was made for Dusty Rhodes, except for one thing: “He is dead now, poor soul.”26 Memorabilia collectors immediately began pestering his wife. Rhodes wrote them back, “Although a lot of people want me gone, I’m still here.”27

He was soon gone from his second marriage, and in 1980 he married Gloria Turco, who owned a New York tavern. Five years later he quit drinking and smoking. “I thought in order to have fun you have to be about half-crocked,” he said. “But after I quit I learned you don’t have to be loaded.”28 He and Gloria retired to Boca Raton, Florida, and later moved to Henderson, Nevada, near Las Vegas.

In 2003 Rhodes told an interviewer, “I’m 76 years old May 13, but I forgot to go to bed for 30 years [so] I’m about 140 years old.”29 Suffering from diabetes and heart trouble, he complained, “I was never sick a day in my life until I quit drinking.”30 Rhodes died at 82 of heart failure on June 17, 2009.

Dodgers broadcaster Vin Scully said, “I remember Dusty saying to me one day with a deadly serious face, ‘They’re giving me a day tomorrow.’ I said, ‘Really, Dusty? That’s great.’ He said, ‘Yeah — to get out of town.’

“Just by mentioning his name, I start to smile — which may be as good a tribute to a man as anything.”31

Acknowledgments

This biography was reviewed by Jan Finkel and fact-checked by Kevin Larkin.

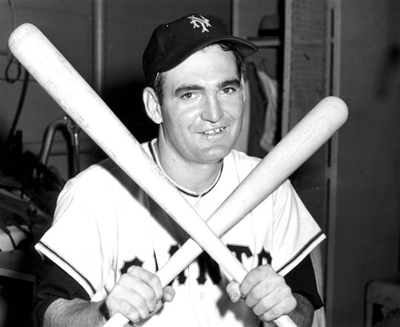

Photo Credit

The Topps Company

Additional Sources

Good, Paul. “Dusty Rhodes #— Wonder of World Series.” New York World-Telegram & Sun, October 1, 1954.

Wancho, Joseph, ed. Pitching to the Pennant: The 1954 Cleveland Indians. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2014.

Weber, Bruce. “Dusty Rhodes, Star Pinch-Hitter in ’54 Series, Dies.” New York Times, June 19, 2009.

Notes

1 Phil Elderkin, “Leo Durocher travels down memory lane, with a stop at Dusty Rhodes,” Christian Science Monitor, June 19, 1985: 18.

2 Will Grimsley, “Introducing Mr. Dusty Rhodes, Pinup Boy of New York Giants,” Associated Press-Florence (South Carolina) Morning News, October 1, 1954: 15.

3 Dusty Rhodes, interview by Rick Swift, May 20, 2003. SABR Oral History Committee collection.

4 Barney Kremenko, “Dusty Made Major Impression Learning Know-How in Minors” New York Journal-American, October 6, 1954: 25.

5 The game was August 5, 1952, a 7-6 victory over Brooklyn in 15 innings.

6 Leo Durocher with Ed Linn, Nice Guys Finish Last (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1975), 260-261.

7 Joe King, “Dusty, Battling to Save Job, Saves Games with his Hits,” The Sporting News, July 14, 1954: 2.

8 Elderkin.

9 Rhodes interview.

10 Ibid.

11 Bill Madden, “Dusty Rhodes, hero of Giants’ ’54 World Series, hits high notes,” New York Daily News, December 20, 2008, in Rhodes’s file at the National Baseball Hall of Fame library, Cooperstown, New York.

12 Ira Berkow, “Rhodes Recalls Glory,” New York Times, October 20, 1981: A26.

13 Durocher, 264.

14 Berkow, A25.

15 Rhodes interview.

16 Durocher, 261.

17 Madden.

18 Kevin Baxter, “Dusty Rhodes Dies at 82; Pinch-Hitting Hero of ’54 World Series,” Los Angeles Times, June 19, 2009, in HOF file; Rhodes interview.

19 Paul Dickson, Leo Durocher, Baseball’s Prodigal Son (New York: Bloomsbury, 2017), 218.

20 Jim Anderson, “35,000 Honor Dusty Rhodes,” Greenville (South Carolina) News, October 7, 1954: 1.

21 Pete Coutros, “It’s never too late for Dusty,” New York Post, July 14, 1989: 88.

22 Rhodes interview.

23 Ibid.

24 Berkow, A25.

25 Madden.

26 Wells Twombly, “Now the 10th Man,” New York Times Magazine, April 1, 1973: 26.

27 Jere Hester, “Mr. October,” New York, October 23, 1989: 46.

28 Rhodes interview.

29 Ibid.

30 Madden.

31 Associated Press, “Former Giant Dusty Rhodes Dead at 82,” Desert Sun (Palm Springs, California), June 19, 2009: 24.

Full Name

James Lamar Rhodes

Born

May 13, 1927 at Mathews, AL (USA)

Died

June 17, 2009 at Las Vegas, NV (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.