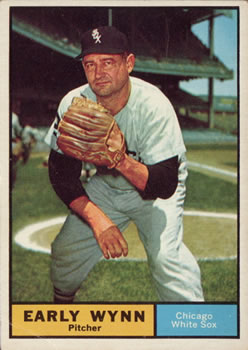

Early Wynn

Chicago fans were outraged when the White Sox traded their most popular player, Minnie Miñoso, to Cleveland in December 1957 with Fred Hatfield for Early Wynn and Al Smith. Wynn was a 37-year-old right-handed pitcher who had posted a losing record for the Indians that season, and his best days appeared to be behind him. However, Wynn joined with Billy Pierce to give the White Sox a formidable one-two punch at the top of their rotation, and his Cy Young Award-winning performance in 1959 led the club to its first American League pennant since 1919. Four years later, at age 43, he became the 14th member of baseball’s 300-win club.

Chicago fans were outraged when the White Sox traded their most popular player, Minnie Miñoso, to Cleveland in December 1957 with Fred Hatfield for Early Wynn and Al Smith. Wynn was a 37-year-old right-handed pitcher who had posted a losing record for the Indians that season, and his best days appeared to be behind him. However, Wynn joined with Billy Pierce to give the White Sox a formidable one-two punch at the top of their rotation, and his Cy Young Award-winning performance in 1959 led the club to its first American League pennant since 1919. Four years later, at age 43, he became the 14th member of baseball’s 300-win club.

Early Wynn Jr., whose family claimed Scotch-Irish and Native American descent, was born in Hartford, Alabama, on January 6, 1920, to Early Wynn, Sr. and his wife, Blanche. Hartford is a small town surrounded by peanut and cotton fields in Geneva County, which borders the Florida Panhandle in the southeastern part of the state. Early Sr. was an auto mechanic and a semipro ballplayer. Early Jr. earned ten cents an hour hauling 500-pound bales of cotton after school. He concentrated on baseball after breaking his leg in a high-school football practice, and at age 17 traveled to Sanford, Florida, to attend a baseball camp operated by the Washington Senators. Legend has it that Early, a husky 6-footer who weighed about 200 pounds, arrived at camp in his bare feet. He did not, Early told writer Roger Kahn years later. “[B]ut I was wearing coveralls.”1 A Washington scout, Clyde Milan, was impressed with Wynn’s fastball and signed him to a contract. The young pitcher dropped out of high school and began his professional career in 1937 with Sanford, the Senators’ farm team in the Class-D Florida State League.

After a 16-11 season, Wynn advanced to the Charlotte Hornets of the Class-B Piedmont League, where he remained for the next three years. The Senators gave him a trial in Washington at the end of the 1939 season, though Wynn was not yet ready for major-league action and went 0-2 in three games. He spent all of 1940 in Charlotte, and then a good season at Springfield in the Class-A Eastern League in 1941 (16-12, 2.56 earned-run average) brought him to Washington to stay. In 1942 he made 28 starts for the Senators, posting a 10-16 mark with a 5.12 ERA as a 22-year-old with little more than a fastball in his arsenal.

In 1939 Early married Mabel Allman, from Morganton, North Carolina, and the couple had a son named Joe Early Wynn. Tragically, the marriage ended prematurely. In December of 1942, Mabel was killed in an automobile accident in Charlotte, where the Wynns lived during the winter months. Early was left with a baby to raise, with the assistance of his relatives. He won 18 games for Washington in 1943, but fell to 8-17 in 1944 as he led the American League in losses. He married Lorraine Follin that September, shortly after entering the US Army. He served in the Tank Corps in the Philippines, spending all of the 1945 season and part of the next in the military before rejoining the Senators.

At this time, Wynn owned an impressive fastball, but had only a mediocre changeup to complement it. He was inconsistent, posting a 17-15 record in 1947 and an 8-19 mark in 1948. Still, he was undeniably talented, and the Cleveland Indians coveted his services. Bill Veeck, the Indians’ owner, tried to acquire Wynn in a trade before the 1948 season, but was rebuffed by Washington owner Clark Griffith. In November 1948 Veeck acquired pitcher Joe Haynes, Griffith’s son-in-law, from the Chicago White Sox. Veeck then offered Haynes to the Senators for Wynn, and Griffith agreed, sending first baseman Mickey Vernon with Wynn for Haynes, pitcher Ed Klieman, and first baseman Eddie Robinson.

The Indians figured that Wynn would become a big winner if he could develop more pitches, so the club assigned pitching coach Mel Harder to teach him how to throw a curve and a slider. “I could throw the ball when I came here [to Cleveland],” recalled Wynn years later in The Sporting News, “but Mel made a pitcher out of me.”2 By mid-1949 he had mastered the curve and slider, and began to use a knuckleball as an offspeed delivery. With a new array of pitches at his command, Wynn joined the ranks of top hurlers in 1950. He won 18 games and led the American League in earned-run average with a 3.20 mark.

Early, nicknamed Gus, got along well with his teammates, but was a grim, scowling presence on the mound. “That space between the white lines – that’s my office, that’s where I conduct my business,” he told sportswriter Red Smith. “You take a look at the batter’s box, and part of it belongs to the hitter. But when he crowds in just that hair, he’s stepping into my office, and nobody comes into my office without an invitation when I’m going to work.”3 With his large frame, grizzled appearance, and willingness to knock down opposing hitters, Wynn stood out as one of the most intimidating pitchers in the game. Roger Kahn, in his book A Season in the Sun, described how the pitcher once brushed back his teenage son during a batting-practice session at Yankee Stadium. “You shouldn’t crowd me,” snarled the elder Wynn. As he explained to Kahn, “I’ve got a right to knock down anybody holding a bat.”4

Wynn hated losing and was never afraid to throw at batters who got too close to the plate or hit line drives at him. Some called him a headhunter, but Wynn regarded close pitches as part of the game. “If they are going to outlaw the inside pitch,” said Wynn in an article he wrote for Sport magazine in 1956, “they ought to eliminate line drives and sharp grounders hit through the pitcher’s box.” To those who suggested that he would throw at his own mother, Early famously replied, “I would if she were crowding the plate.”5 One day Mickey Mantle drilled a liner through the box for a single. Wynn then fired several pickoff attempts at Mantle’s legs. “You’ll never be a big winner until you start hating the hitter,” he told rookie pitcher Gary Bell. “That guy with the bat is trying to take away your bread and butter. You’ve got to fight him every second.”6

His toughness and durability made Wynn part of one of the greatest pitching rotations of all time in Cleveland, with Wynn, Bob Lemon, Bob Feller, and Mike Garcia all posting 20-win seasons during the early 1950s. Under the tutelage of Mel Harder and manager Al Lopez, Wynn won 20 games or more in a season four times for Cleveland, and anchored the rotation that led the Indians to the American League pennant in 1954. In the World Series that year Early lost to the New York Giants 3-1 in the second game, giving up three runs in seven innings. He did not have the chance to pitch again in the Series, as the Giants cruised to the title in four games.

Early and Lorraine made their permanent home in Nokomis, Florida, where they raised his son, Joe, and their daughter, Sherry. He spent his leisure hours hunting, driving powerboats, and flying his own Cessna 170 single-engine plane. Beginning in 1955, Wynn produced a regular column for the Cleveland News, titled “The Wynn Mill,” and donated the money he earned from the effort to the Elks Club in Nokomis. Though he had dropped out of high school, Early wrote without the assistance of a ghostwriter, and his frank assessments of umpires, league policies, and his own management rankled Cleveland team officials and strained his relationship with general manager Hank Greenberg.

Wynn notched another 20-win campaign in 1956, but in 1957 he posted his first losing season in Cleveland (14-17, with his ERA leaping from 2.72 to 4.31) despite leading the league in strikeouts. The careers of both Bob Feller and Bob Lemon drew to a close during this time, and perhaps the Indians believed that the 37-year-old Wynn was fading as well. On December 4, 1957, the team traded Early to the Chicago White Sox. The White Sox inserted a clause in his contract that prohibited the pitcher from writing for newspapers, but the team compensated him for the lost income. Reunited with his old Cleveland manager Al Lopez, who had resigned and taken the Chicago job after the 1956 season, Wynn compiled a 14-16 record in 1958, leading the league in strikeouts again.

Wynn was still a tough competitor, sometimes throwing chairs in the locker room after losses. He hated to be taken out of games, though his advancing age often made it necessary to use relievers to finish his wins. In 1992 Al Lopez described Wynn’s competitiveness to biographer Wes Singletary. “So this one day Early was arguing with the umpire,” said Lopez, “when I came out there and he threw the ball at me, hitting me in the stomach. It was more of a flip/toss but the press played it up. I said give me the goddamned ball and don’t be throwing it at me. After the game he came and apologized to me. I said, Early, I know how you feel but the people upstairs, the fans and media, they see that and think you’re mad at me. I told him don’t get mad at me, get mad at the guys who are hitting.”7

Wynn had suffered from gout since the 1950 season and pitched in pain for the last half of his career. Still, he kept in good shape, and his fastball remained sharp as he approached his 40th birthday. Lopez kept Early at the top of the Chicago rotation, and in 1959, everything clicked for both Wynn and the White Sox. On May 1 the 39-year-old pitched a one-hit shutout against the Boston Red Sox and hit a home run that provided the only scoring in the 1-0 victory. He led the league in innings pitched, started that season’s first All-Star Game for the American League, and won a league-leading 22 games, pitching the White Sox to their first American League flag in 40 years. Early’s 21st win of the season, a 4-2 victory over Cleveland on September 22, clinched the pennant and set off a night of celebration on Chicago’s South Side. At season’s end, Wynn won the major-league Cy Young Award and finished third in the American League Most Valuable Player balloting behind teammates Nellie Fox and Luis Aparicio.

The White Sox faced the Los Angeles Dodgers in the 1959 World Series, and Early pitched seven shutout innings in the opening game, teaming with reliever Jerry Staley to defeat the Dodgers by an 11-0 score. However, he struggled in the fourth contest, played at the Los Angeles Coliseum before 92,650 fans. He failed to complete the third inning of a game that the White Sox eventually lost, 5-4, though Staley was the losing pitcher. In the sixth game, played in Chicago, a six-run Dodger explosion in the fourth inning knocked Wynn out of the game and saddled him with the Series-ending defeat.

Wynn’s 13 wins in 1960 left him with 284 career victories, and the pitcher announced his intention of joining the 300-win club before his retirement. He pitched well in 1961, with eight wins in his ten decisions, but arm soreness, caused by gout, ended his season in July. He gave up eating meat in an attempt to control his gout problem, but the pain persisted, causing problems with his legs and right hand. He fell short of his 300th win in 1962, posting a 7-15 record while relying mostly on a slider and a knuckleball. His seventh win, a complete-game effort against the Senators on September 8, was the 299th of his career, but Early failed in three subsequent attempts to gain number 300. The White Sox were convinced that the 42-year-old pitcher had reached the end of the line, and in November the team released him.

The White Sox invited Wynn to their 1963 spring-training camp, but he failed to make the team. He returned home to Florida, where he stayed in shape and waited for a call from another club. A few teams offered Early one-game contracts, seeking to capitalize on his quest for 300 wins, but Wynn held out for a season-long deal. In June his old club, the Cleveland Indians, signed Early for the rest of the season and put him in the starting rotation. On July 13, in his fourth start of 1963, he pitched five innings against the Kansas City Athletics and left the game with a 5-4 lead. Reliever Jerry Walker held the Athletics scoreless the rest of the way, giving Wynn his 300th, and final, win. He was the first man to win 300 games in the American League since Boston’s Lefty Grove reached the mark in 1941.

Wynn started only one more game for Cleveland and retired at the end of the season. His career record stood at 300-244 with an ERA of 3.54. Early remained with the Indians, succeeding Mel Harder as Cleveland’s pitching coach in 1964. He moved to the Minnesota Twins in 1967, and then managed in the minor leagues for one season. In 1972, in his fourth year of eligibility, Wynn was elected to the Baseball Hall of Fame. He had been disappointed in not gaining the honor earlier, once calling the institution the “Hall of Shame” in an interview. After his election, he told The Sporting News, “I would have been happier if I’d made it the first year. I don’t think I’m as thrilled as I would have been if that had happened. But naturally I’m happy. So is my wife. We’ve had a long wait.”8

Early Wynn worked as a broadcaster for the Toronto Blue Jays and the Chicago White Sox after his election to the Hall of Fame, and also owned a restaurant and bowling alley for a time. He fully expected to be the last of the 300-game winners, and often referred to himself in such terms in interviews. Nineteen years passed between Wynn’s final victory in 1963 and Gaylord Perry’s ascension to the 300-win club in 1982. As it was, Early saw six pitchers, including Perry, surpass his total during the 1980s and ’90s. By the end of the 2013 season, Wynn was one of 24 pitchers with 300 wins or more.

Wynn retired during the mid-1980s and resided in Nokomis until his health began to fail after the death of his wife, Lorraine, in 1994. He suffered a heart attack and a series of strokes during the final years of his life, and spent his remaining days in an assisted-living center in Venice, Florida, where he died on April 4, 1999, at the age of 79.

An updated version of this biography is included in the book “Pitching to the Pennant: The 1954 Cleveland Indians” (University of Nebraska Press, 2014), edited by Joseph Wancho. It also appeared in “Go-Go To Glory: The 1959 Chicago White Sox” (ACTA, 2009), edited by Don Zminda, and “Van Lingle Mungo: The Man, The Song, The Players” (SABR, 2014), edited by Bill Nowlin.

Sources

In addition to the sources cited in the Notes, the author consulted a number of other sources including Marty Appel and Burt Goldblatt, Baseball’s Best: The Hall of Fame Gallery (New York: McGraw-Hill, 1980), 400-401.

Notes

1 Roger Kahn, “Early Wynn: The Story of a Hard Loser,” Sport, March 1956.

2 The Sporting News, June 15, 1963, 7.

3 Red Smith, Red Smith on Baseball (New York: Ivan R. Dee, 2000), 325.

4 Roger Kahn, A Season in the Sun (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2000), 108.

5 Early Wynn, “The Four Sides of the Beanball Argument: The Pitcher’s Side,” Sport, January 1956.

6 The Sporting News, October 7, 1959.

7 Wes Singletary, “Señor: The Managerial Career of Al Lopez,” The Sunland Tribune (Journal of the Tampa Historical Society) 19, November 1993, 57-66.

8 The Sporting News, February 5, 1972.

Full Name

Early Wynn

Born

January 6, 1920 at Hartford, AL (USA)

Died

April 4, 1999 at Venice, FL (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.