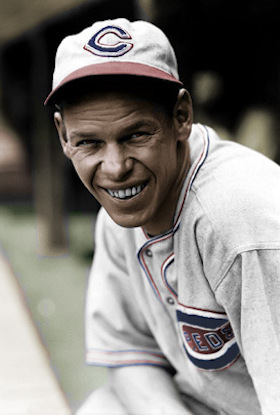

Babe Herman

Throughout baseball history, careers have often been defined by a specific play or events. Joe DiMaggio is recalled for his 56-game hitting streak; Willie Mays for his catch in the 1954 World Series. Likewise, players can be maligned for ineptitude, real or perceived. Fred Merkle’s race-altering baserunning gaffe in 1908 and Bill Buckner’s inability to handle a ground ball in the 1986 World Series have forever labeled them in the collective memory of baseball.

Throughout baseball history, careers have often been defined by a specific play or events. Joe DiMaggio is recalled for his 56-game hitting streak; Willie Mays for his catch in the 1954 World Series. Likewise, players can be maligned for ineptitude, real or perceived. Fred Merkle’s race-altering baserunning gaffe in 1908 and Bill Buckner’s inability to handle a ground ball in the 1986 World Series have forever labeled them in the collective memory of baseball.

Babe Herman is often recalled for zany baserunning, fielding lapses, and off-the-field malapropisms. There are some who contend these kept him out of the Hall of Fame. They seemingly overshadow a 13-year career which produced a lifetime batting average of .324 and an impressive number of Dodger franchise season records still in effect. The reputation Herman deserves needs proper perspective.

Floyd Caves Herman, the fourth of five children, was born on June 26, 1903, in Buffalo, New York, the son of Charles and Rosa (née Caves) Herman. The family was of English-German ancestry. Shortly after Floyd was born, they moved to Los Angeles because, as a 1990 Herman biography noted, Rosa was terrified of lightning and thunder. She persuaded her husband to move west, where, she’d heard, neither occurred. Charles, a contractor, soon found work constructing several houses in the Verdugo Mountains region.1 In 1917 the family moved to Glendale, where Charles built a house for the family.

Floyd began attending Glendale Union High School and immediately established himself as an all-around athlete, earning varsity letters in baseball, basketball, football, and track.

He became an immediate standout in baseball when his only at-bat as a freshman generated a game-winning grand slam. Herman went on to hit .800 as a sophomore, and played as a left-handed third baseman before moving to first base as a senior. He had football scholarship offers from Dartmouth and Stanford, but fate intervened during his senior year through a seemingly innocuous invitation to play a semi-pro game on Catalina Island.

Under then-existing rules, players were allowed to participate in semi-pro games without affecting eligibility only before and after the high school season. One game into Glendale High’s season, the local Elks Club invited Floyd, then a senior, to play in a weekend game on Catalina. He was fully aware that he was risking his eligibility. “I took a chance and went along. Maybe I’d have got away with it but I hit two home runs and the school coach heard all about the affair and grew very indignant.” Floyd took responsibility for his actions and was suspended for the year.2

Around that time, Floyd was approached by the owner of a local sporting goods store inquiring whether he might be interested in playing professional baseball with Edmonton in the Class B Western Canada League.3 “Well, it looked like a long summer and I didn’t see much to do. I thought of that offer of $200 a month and finally decided to grab it,” Herman remembered.4

His father cautioned against leaving before graduation. Charles could not understand getting paid to play ball, especially when his son could have followed in his footsteps as a contractor. But lured by the money, Herman signed with Edmonton. The 1921 Eskimos featured 19-year-old Heinie Manush, in his second season. Herman (.330, seven home runs) and Manush (.321, with a league-leading nine homers) formed a solid one-two punch. Herman paced the league in hits and triples, missing the batting title by five points. The Sporting News observed: “There is yet a youthful prodigy who tops the others as a prospect of future greatness. This is the 18-year-old high school giant. Herman [is] a left-handed colossus.”5

In Edmonton Herman gained the nickname he would carry the rest of his life. A woman fan often exhorted that “Babe” get a hit during the games. The next spring when Herman was with Detroit in camp, Coach Dan Howley asked him what he was called. Herman replied, “Lefty.” Howley replied that would not do – it was too common. Herman mentioned what his feminine admirer in Canada had called him, and Howley responded, “From now on you’re my Babe.”6 Years later Herman’s son Charles shared an alternate story, that his father made a pinch-hit in spring training and the manager, thinking of Babe Ruth, said “You’re my Babe.”7

Herman’s initial minor-league sojourn spanned eight minor league clubs over five seasons. He hit .330, .402, .339, .326 and .316 respectively. This, plus his power, indicated that he probably should have reached the majors earlier.8

Why it took him five years to arrive can be gleaned from The Sporting News and Tot Holmes’s 1990 Herman biography. The saga began in 1922 when Detroit sent Herman a contract which he rejected because he deemed the salary insufficient. This stance, highly unusual for a one-season minor leaguer, did not endear him to Tigers management. But holdouts, although they irritated baseball executives, became something Herman employed several times during his career.

Herman showed up in the 1922 Detroit camp, confident that once the Tigers saw him play, his demands would be met. He impressed manager Ty Cobb. When Herman hit a long home run, Cobb told him, “Don’t ever try to copy Ruth. He perfected that big swing and doesn’t worry about his strikeouts. Anyone else would have trouble even hitting the ball with that swing and would be back in the minors in no time.” Still, Cobb farmed Herman out to the Class A Omaha Buffaloes. “I like you, but you’re so young I hate to keep you on the bench,” was Cobb’s rationale.9 How Herman’s salary demands were resolved is unrecorded, but he would have faced the difficult hurdle of replacing first baseman Lu Blue. In the outfield were future Hall of Famers Cobb and Harry Heilmann, and hard-hitting Bobby Veach. He was in the wrong place at the wrong time.

Herman’s time with Omaha was unsettling. Early on, he made a bad impression when inattention to baserunners during an argument with an umpire allowed two runs to score. Temporarily benched, he got several clutch pinch-hits, earning more playing time. By mid-May, exasperated at not playing full-time although hitting over .400, Herman contacted Tigers’ president Frank Navin and asked where he could be sent to play more. Navin transferred him to the Reading (Pennsylvania) Aces in the higher-classification International League to fill in for a disabled player. When the player recovered, Herman went back to Omaha. Injuries there allowed him to crack the lineup.

During the summer of 1922 Charles Herman came to Omaha on business. Though he still questioned why people paid to watch baseball, he agreed to attend Floyd’s games while in town. Babe pounded out several doubles and a home run, convincing his father that maybe there could be a future in the game. Thirty years later, Herman called this his greatest thrill in baseball.10

Herman finished at .416 with Omaha. Writers touted his ability, but ominously added, “Herman got in a bit bad through his wanderings and vagaries of temperament this past season.”11 Salary squabbles with Detroit led him to threaten contacting baseball Commissioner Kenesaw Landis. The Tigers placated him, but Navin sent him to the Red Sox in October 1922. Detroit had had enough of their eccentric prospect.12

Herman impressed Boston manager Frank Chance in 1923 spring training but his ability to make the team was again blocked by a solid veteran – this time first baseman George Burns. Chance offered a spot as a bench player but Herman demurred and was sent to the Atlanta Crackers of the Southern Association. Although he hit well, Herman again ran afoul of management. Manager Otto Miller questioned Herman’s play and the 19-year-old challenged Miller, 14 years his senior, to a fight. Miller refused and decided to get rid of him.13 Herman moved on to the Memphis Chickasaws for the rest of the 1923 season.

That offseason Floyd, at 20, married Anna (Ann) Merriken, his childhood sweetheart, on November 9, 1923.14 It was one of the best decisions Herman ever made. Ann provided a stable home life and a sense of direction, especially after Babe’s playing days ended.

Herman went to 1924 spring training with Boston before being sent to the San Antonio Bears in the Texas League. He played well for the Bears, but again courted trouble. He was approached by friends playing for the Dallas Steers, also in the Texas League, who convinced Herman that if he were with Dallas they could win the championship.15 Herman asked his manager, Bob Coleman, for a transfer to Dallas. Coleman, nonplussed, agreed a transfer could be made – then shipped Herman to the Little Rock Travelers in the Southern Association. Coleman blasted Herman’s indifferent play: “He thinks he is a big leaguer and he sneers at this league. If he gets a couple of hits, he wouldn’t worry about anything else; that’s the attitude he’s been taking.”16 Coleman’s insight did reflect Herman’s approach to the game then.

Herman hit well at Little Rock and local fans initially appreciated his presence. But injuries soon affected his play and he asked manager Kid Elberfeld for a few days off to recover. Elberfeld, under pressure for the team’s poor play, refused; Herman left the team and went home. His season was done. Herman had now played parts of four years for seven teams, always causing controversy but not attaining his potential.17

Wade “Red” Killefer, manager of the Pacific Coast League’s Seattle Indians, had tried to get Herman from Boston at the start of the 1924 season but was rebuffed. A year later, Boston obliged. Herman got a manager known for bringing out the best in his players.18 Killefer knew of Herman’s poor reputation but saw a possibility for change. In his opinion, Herman had “married and settled down to playing real ball.”19

Killefer was right. In 1925, Herman hit .316 and made the PCL all-stars – but more significantly, Killefer said he hoped Herman would play for him in 1926. It was the first time a manager wanted him back.20

But it didn’t work out that way; the Brooklyn Robins signed Herman. During the 1925 season scout Spence Abbott had visited the PCL to check out prospects. He encountered Herman amid a hitting spree. Abbott wrote to Robins’ manager Wilbert Robinson, “He’s sort of funny in the field, but when I see a guy get six-for-six I’ve got to go for him.” Abbott’s appraisal led Brooklyn to purchase Herman’s contract.21 He finally seemed poised to make the majors – but another obstacle arose.

For years Robinson had tried to fill a hole at shortstop. He became enamored of Johnny Butler, who had hit .339 with the Minneapolis Millers in 1925.22 To get Butler, Brooklyn had to part with several players, including Herman, on an option.23 He was placed in the mix because the Millers’ first baseman was ailing and they needed a backup. Then Herman caught a break when the player recovered and Minneapolis returned him.24 Herman made the Robins’1926 Opening Day roster as backup to first baseman Jack Fournier, who was coming off a .350, 130-RBI season.

Herman had an unlikely backer in Brooklyn – Otto Miller, his nemesis from Atlanta, was now a Robins coach. He gave Herman a warm welcome and told Robinson that while he and Herman had clashed a few years before, he realized he had mishandled the situation – Robinson ought not to ride Herman. Robinson complied, easing the way for Herman.

The rookie, now 22 , joined a team that had descended into extended oblivion. Owner Charles Ebbets died in 1925, setting off a chain of events that thrust Robinson into dual roles as field manager and club president. Robinson was unsuited to be Brooklyn’s chief executive. Pressures of his new position transformed him from a confident manager into a bewildered, confused, and inconsistent leader.25 Robinson, increasingly frustrated, began feuding with the local press, the New York Sun in particular, and after one acrimonious episode the paper ceased mentioning Robinson by name. This came against a backdrop of second-division finishes – confusion in the Robins’ executive office bred confusion on the field.26

And the press exploited that confusion. The Robins might have been treated differently if they were the only franchise in town. But they shared a metropolitan area with the Giants and Yankees. Numerous newspapers competed for readership among baseball fans. Writers covering Brooklyn had little success to report, especially when compared to their cross-city rivals. So they tried to make the Robins interesting. Coverage of the team took an approach similar to one honed decades later, when Casey Stengel’s expansion New York Mets became popular as “lovable losers.”

Thus, the “Daffiness Boys” came into being. Daffy comments, daffy developments, and daffy plays formed the core of coverage. And, warranted or not, the press chose Herman, who quickly became the most identifiable player on the Robins, as their favorite Daffiness Boy.

The rookie’s first appearance came on April 14 at the Polo Grounds. He pinch-hit, working a walk off Giants’ pitcher Jimmy Ring. Over the next two weeks, Herman unsuccessfully pinch-hit twice more. But on April 28 at Boston’s Braves Field, Herman’s pinch-hit double ignited a winning three-run rally in the ninth inning.

Less than a week later, on May 4, Fournier injured his ankle. Herman replaced him at first, with immediate impact. He singled in the bottom of the ninth and scored the winning run.27

Herman soon launched an 11-game hitting streak, keeping the now-recovered Fournier on the bench. The Sporting News noticed that “[Herman] has not only been hitting, but has been fielding grandly at first.”28 By the time Herman’s hitting streak ended the team had fallen to third. Looking for punch, Robinson re-installed Fournier at first and moved Herman to right field for the second game of a doubleheader at the Polo Grounds on May 25.

Herman drove in a run on two hits and fielded well in the new position, throwing out Ross Youngs at the plate. While Brooklyn lost both games, beat writer Tommy Holmes noticed something. To that point, Herman had appeared in just a handful of home games. Brooklyn fans who trekked to the “road” games in Manhattan had taken a liking to the 22-year-old rookie. “He has that intangible thing called color. Crowds take to him instinctively. He is likely to step out and give the crowd a thrill at any moment.”29 It was the beginning of an on-and-off love affair between the “other Babe” and Brooklyn fans.

Herman stayed hot; in early July he took over the league lead in batting.30 By mid-August, with the Robins in sixth, Herman had become their standout player – especially with hitting, for a team last in the league in offense. His outfield skills were lacking, but it was an understood that he was doing his best in an attempt to boost the team’s run production.

On August 9-11, against Pittsburgh at Ebbets, he got nine straight hits, one short of what was then believed to be the National League record for consecutive hits. A “murderous line drive” directly at Kiki Cuyler ended his streak. 31

Four days later, Brooklyn played a home doubleheader against the Braves. In the opener, the Robins tied the game at 1-1 in the bottom of the seventh. One of the more infamous plays in baseball then ensued – the erroneously described “Herman tripling into a triple play.”

There were 15,000 in attendance that day – and about as many accounts of the play. The facts: with one out and the bases loaded, Herman hit a fly to right. It was questionable whether the ball would be caught; when it hit the wall, all three runners took off. Lead runner Hank DeBerry scored the go-ahead run. Dazzy Vance, starting from second, rounded third, but reversed himself and came back to third. From first, Chick Fewster, watching Vance start for home, ran to third at the same time Vance came back. Herman slid into second and took off for third when he saw a throw home. With Vance already at third, Fewster and Herman were tagged out. Lost in customary accounts of the play is the fact that Herman’s double was the game-winning hit. Brooklyn swept the doubleheader, winning the second game as Herman contributed three RBIs.32

The next day, Tommy Holmes of the Eagle described the games as somewhat boring, “So far as the fans were concerned, both affairs were as listless and uninteresting as one can imagine.” Almost as an aside, he commented, “One good laugh relieved the ennui and that was all.” Then Holmes gave a garbled description of the play. He had DeBerry tripling, Herman without any runs driven in, and several other factual errors.33 Over the next few weeks, the play faded from sight.

Yet it somehow lived on. Many clippings in Herman’s Hall of Fame file refer to this play, varying widely in accuracy. The articles typically speculate as to who was at fault: Vance, Herman, or one of a series of individuals identified as coaching third. Ring Lardner’s “Babe Herman did not triple into a triple play, but he doubled into a double play, which is the next best thing,” became etched into baseball history.34

Hank Aaron passed a baserunner in the 13th inning as the Milwaukee Braves weathered Harvey Haddix’s twelve perfect innings in 1959. Babe Ruth’s ill-advised attempt to steal second ended the 1926 World Series. These incidents did not define either Hall of Famer’s career. With Lardner’s “help,” Herman’s involvement in this play seems to have defined his.

At the time Herman was hitting .343, among the league leaders. But a series of minor injuries caught up with him as the 1926 season wound down, and by the end of the year Herman had a .319 average and 81 RBIs to lead the Robins. His 11 home runs tied Fournier for most on the sixth-place Robins. The Eagle’s Tommy Holmes lauded Herman’s rookie year. He had outhit such NL luminaries as Rogers Hornsby, Frankie Frisch and Jim Bottomley. Though Herman’s fielding left something to be desired, Holmes recognized the potential for improvement.35

During the offseason, Herman returned to California, where among other endeavors, he doubled for Tris Speaker in “Slide Kelly Slide,” a baseball-themed movie. It would not be the last time Herman was associated with the film industry. He also finished requirements for his high school diploma, fulfilling his mother’s wish that one of her children be a high school graduate.36

Based on Herman’s strong performance in 1926, the Robins released Fournier and future Hall of Famer Zack Wheat. These departures put added pressure on Herman, for Brooklyn did little to shore up an anemic offense. One sub-headline in The Sporting News summed up Herman’s situation as the 1927 season opened: “Early Contests Show Barrett and Herman Hold Team’s Fate.”37

Herman slumped to .272 in 1927 with 14 home runs and led the league in errors by first basemen with 21. A crowd-pleaser the year before, Herman now bore the brunt of criticism for Brooklyn’s poor play. He lost his place in the lineup and was reduced to pinch-hitting. He had abscessed teeth, which became so painful that Herman had them pulled in July, instead of after the season.38 The effects lingered until September, when Herman regained his starting position.

Brooklyn finished sixth again. Although the Robins had the best ERA in the league, their offense was abysmal. The team was in turmoil – Robinson’s open quarrels with team co-owner Steve McKeever created an aura of ineptness. Herman, the team’s most prominent player, was seen as epitomizing the situation. He wasn’t counted on to play much of a role in 1928, perhaps best summarized in a Sporting News article by Thomas Rice in spring training. “Herman has been catching more and more flies in right field without stepping on his own feet,” he wrote, reflecting a growing perception of clownishness.39

Del Bissonette, who had hit .365 with 168 RBIs for Buffalo in the International League the prior season, won the first base job in 1928 spring training. Robinson planned to put Herman in right field. Herman thought the switch good for the team. “Personally I don’t care where I play as long as they let me take my regular turn at bat.”40

The move benefited Brooklyn. Bissonette hit .320 with 25 home runs and 106 RBIs.41 Herman rebounded with a .340 average, fifth in the league, 12 home runs, and 91 RBIs. Waiver-wire acquisition Rube Bressler also boosted the offense. Brooklyn had the NL’s best ERA, and finished over .500 for the first time since 1924, at 77-76. Though it was good for only another sixth-place finish, the Robins had still made progress.

Herman’s reputation got another blemish in 1928 – when he was supposed hit on the head by a fly ball. Unlike Herman’s well-documented 1926 baserunning adventure, specifics on this are vague. According to Babe’s version, the official scorer failed to record a defensive change to Ty Tyson, the player who in realitywas hit. Writers, unaware of the change, pinned the mishap on Herman. Herman’s version sounds plausible. Tyson was with Brooklyn in 1928 and box scores reveal he replaced Herman in the late innings several times. There are no references to a misplay on Tyson’s part – and it is telling that the Eagle, which covered the Robins in depth, fails to mention any such incident involving Herman during the 1928 season.

Whether in 1928, some other year, or ever, this reinforced a perception of Herman’s ineptness. When asked about it in later years, Herman’s’ response was a breezy “On the shoulder, yes, never on the head!”42 Another stock response was, “The ball actually hit me in the shoulder but the writer reported it hit me in the head. It made for a better story, so I let it go.”43

Eagle writers often referred to Herman’s outfield play with an acerbic edge. “Babe Herman spent a normal afternoon. The gangling blond committed a two-base muff of a fly ball.”44 “Babe is still a great outfielder except for his inability to catch fly balls.”45 “You may laugh at Babe’s inexorable pursuit of line drives off the left field wall.”46 These and numerous other jibes created a popular image over time of Herman as an inept fielder. There was some hyperbole, but Herman did in fact lead National League outfielders in errors with 16 in 1928.

That season the Eagle interviewed Tom “Oyster” Burns, an outfielder for Brooklyn in the 1890s. When asked to comment on the current club, Burns mentioned how he appreciated Herman’s batting prowess. He also noted, “Herman’s stationed in a bad field. It’s short and it’s sunny and the fence has him scared.”47

Herman’s 1928 offensive comeback put him in a good position during contract negotiations for 1929. By now, the persona of a temperamental youngster had been replaced by that of a hard-headed businessman. Genial with the press and willing to talk about his craft, he often played tough with management. After the club agreed to his salary figure for 1929, Robinson challenged Herman, asking why he stole only one base in 1928. “Cripes Robbie, you never sent me,” Herman responded.48 Working on technique with teammate Max Carey, a 10-time NL stolen base leader, Herman swiped a career-high 21 bases in 1929, but by the end of the season it wasn’t his base stealing that caught the attention of fans.

National League offenses exploded during the 1929 season. Herman took advantage as he batted .381. Though his mark was second-best in the NL, 10 batters in the league hit .353 or better. The leader, Philadelphia’s Lefty O’Doul, hit .398. Herman had been hitting .400 until September 1 and led until September 21, but O’Doul hit .438 from September onward and pulled away.

Herman’s 113 RBIs were only eleventh in the league, but Brooklyn’s offense gained further balance from rookie Johnny Frederick, who hit .328 with 52 doubles (then an NL record). Despite this firepower the Robins finished sixth for the fifth straight season. Herman’s efforts gained him eighth place in the 1929 NL MVP voting and selection to Babe Ruth’s All-American team – the most prestigious all-star selection at the time.49

If 1929 was a breakout season for Herman, 1930 proved even better, as the surge in offensive production continued. The entire National League averaged .303, scoring 7,025 runs. Both broke records set in 1929. Robinson finally had a pennant-contending team – the Robins improved through a series of trades, minor league acquisitions, and solid years from virtually all of their returning players.

Herman contributed in 1930 as well, but only after another holdout, this one protracted. The Sporting News reported that he “had the audacity to demand $25,000 for the season” but ventured that he could be signed for $18,000.50 With a little more than two weeks left before the season started, Herman finally signed at somewhere between $15,000 and $19,000.51 Missing much of spring training had little effect on him as the season began. After going hitless in the opener against Pittsburgh, Herman got two hits in six straight games. By the end of April he was batting .429.

As Babe continued to hit at a .400 clip, a new aspect of his game attracted attention. Tommy Holmes, stringing for The Sporting News, observed, “a vastly improved outfielder, Herman has yet to make an error this season. He is another one of the reasons why Brooklyn is winning.”52 Several weeks later Herman was the subject of the player profile feature on Page 1 of The Sporting News. Not only his hitting but also his fielding was lauded; he was described as “suddenly transplanted into a master fly hawk.”53 The Eagle, too, took note of his fielding in a game against St. Louis on June 16, citing a one-handed catch of a potential triple to preserve a tie in a game the Robins eventually won.54

Brooklyn was in first place as late as September 15 before fading to fourth, snapping a five-year streak of consecutive sixth-place finishes. Herman’s performance in 1930 dazzled. He batted .393 with 35 home runs and 130 RBIs, all career highs. Along the way he amassed 416 total bases (with 94 extra base hits, including 48 doubles), 143 runs scored, and a .678 slugging average. Through the 2014 season, all except for homers are still Brooklyn-Los Angeles franchise records.

Herman hit over .400 until late August, but never caught the Giants’ Bill Terry, who ended at .401. Even with a combined .387 average and 458 hits over the 1929-30 seasons, Herman did not lead the league in hits, batting average, or any other offensive category in either year. Terry was named National League MVP for 1930 by The Sporting News; Herman was fifth.

Despite Babe’s career year, his relations with the Robins’ front office had deteriorated. Robinson had been removed from the club presidency – he was unsuited to the dual role. The new president, attorney Frank York, immediately got into a dispute with Herman over salary, which played out in the press over the 1930-31 offseason. Herman returned the contract proffered him unsigned and announced another holdout.

Babe finally came to terms in March 1931. Although he led Brooklyn in home runs and RBIs in 1931, the numbers shrank from 35 to 18 and 130 to 97.55 Coming off a pennant chase, and having made several changes (including a trade for Lefty O’Doul), the season as a whole was a letdown – the Robins finished fourth again, but 21 games back. However, Babe became the first of only two players since 1900 to hit for the cycle twice in a season (he did it on May 18 and July 24).56

At the end of the season Brooklyn replaced manager Robinson with Max Carey. Herman and York got into another salary scuffle. York wanted him to take a deep cut and Herman held out again. The impasse was exacerbated when the Dodgers (who returned to their 1911 and 1912 moniker with Robinson’s departure) brought in slugger Hack Wilson at a salary higher than the one offered Herman, although Wilson had hit only .261 with 13 home runs with the Cubs, well below Herman’s 1931 production. Frustrated by yet another Herman holdout, York traded him, Ernie Lombardi and Wally Gilbert to Cincinnati on March 14, 1932.

Except for one solid season in Cincinnati, once Babe left Brooklyn, the rest of his career was anticlimactic. He played for four teams over the next six seasons and was never again the preeminent player he had been for Brooklyn. When he joined the Reds in 1932, they were a last-place team and would remain so the next three seasons.

Herman’s 1932 was still pretty productive. He led the 1932 Reds in batting (.326), homers (16), and RBIs (87). While 16 home runs might seem modest, then it was the second most ever hit by a Cincinnati player.57 Herman led the league in triples with 19. Perhaps one of his most successful days came on a return trip to Brooklyn on June 15. He went three-for-four against the Dodgers with a double, home run, and three RBIs to pace a 5-1 victory. Cincinnati won the next day as Herman drove in two runs. The Eagle’s coverage, suggesting possible Dodger remorse, was headed by an apt “Who’s Sorry Now?”58

Herman improved his once-suspect fielding in Cincinnati. He led 1932 NL right fielders in putouts with 392, establishing a still-standing major league record. And he did it in 146 games of the 154-game schedule.

Yet Herman was traded again. Sidney Weil, owner of the Reds, was suffering financially. To provide working capital, Weil had to turn Herman into cash; he asked Babe where he would prefer to be traded. Given the choice of 1932’s first-place Cubs or sixth-place Giants, he chose Chicago. Weil obliged, and on November 30, 1932, Herman went to the Cubs for $75,000 and four players. It was an opportunity lost – the Giants won the pennant in 1933.

Herman stayed with Chicago for two seasons. By then, though, his skills were eroding, mostly due to nagging injuries. In 1933 his average fell to .289 and he missed 17 games. A highlight for Herman, however, came near the end of the season when he hit for the cycle again – he and Bob Meusel are the only big-leaguers since 1900 to do it three times in their careers. The next season the Cubs finished third again; Herman contributed a .304 average, although he missed 27 games. His average picked up but his extra-base hits had dwindled from 77 in 1931 to 53 in 1934.59

Babe was traded to Pittsburgh after the 1934 season.60 Not about to dislodge Lloyd or Paul Waner from their outfield positions , he was penciled in to start in left . Herman exuded confidence as spring training started: “I play left and there won’t be any complaints after I get started.”61 Herman started 1935 slowly – injuries played a role. Under .250 at the beginning of May, he was reduced to pinch-hitting and an occasional game at first base. Herman watched from the bench in Forbes Field on May 25 as Babe Ruth, playing out the string with the Boston Braves, hit three home runs, the last of his major league career.62

On June 21 Herman was shipped back to Cincinnati. Pittsburgh sought to unload Herman’s substantial salary and the Reds needed to replace an ailing Chick Hafey.63 He hit .335 for Cincinnati, and when he homered against the Dodgers on July 10 at Crosley Field. it was the first home run in a major league night game; the Reds had inaugurated night baseball on May 24. 64

The 1936 Reds climbed to fifth. Babe, now 33, was an older veteran, and nagging injuries again limited his playing time. He hit .279 with 71 RBIs in 119 games.65

Herman’s elevated salary, advancing age, and inability to play every day led the Reds to place him on waivers in the spring of 1937. Initially there were no takers but eventually the Detroit Tigers purchased his contract. The 11-year National League veteran had come full circle, back to the American League and the team with which he had signed his first professional contract.

Detroit manager Mickey Cochrane used Babe primarily as a pinch-hitter – in Herman’s 17 games, just two were in the field. Late in May, the team went with Pete Fox, Gee Walker and Jo-Jo White in the outfield. Herman became surplus. He was released June 15 and immediately caught on with the American Association Toledo Mud Hens. In 85 games, he hit .348 there.

In 1938 Herman signed with the Jersey City Giants of the International League and played in 145 games, hitting .324. 66 Jersey City sold his contract to the Hollywood Stars of the Pacific Coast League for 1939.

The Stars had been purchased by Bob Cobb, president of the Brown Derby restaurant chain in Southern California. Cobb, seeking to use the aura of Hollywood to promote the team, brought in ownership partners such as Bing Crosby, Gary Cooper and Barbara Stanwyck.67 Cobb also saw his purchase of the colorful Herman’s contract as a stroke of genius – bringing the “local boy” back home.

Herman did not disappoint. Playing for Hollywood through 1944, increasingly as a pinch hitter, he always hit over .300, still showing occasional power. In 1941, his .346 was the best in the Pacific Coast League; only insufficient at-bats prevented him from winning the batting title. His popularity was recalled years later by fan Dick Bank in a letter to the Los Angeles Times: “He was a genuinely friendly man who always had time for us kids. The team never finished higher than fifth or had a winning record, but each season he batted well over .300 and hit enough home runs to give us plenty of thrills. If you were fortunate enough to live close by and could spend your Saturdays and Sundays at that wonderful park, it was made even better because of “the other Babe.”68

In 1942, Herman’s proximity to the film industry brought him an opportunity to play a role in one of the most popular baseball movies of all time, “Pride of the Yankees,” the Lou Gehrig story. Gary Cooper, who portrayed Gehrig, had never played baseball and was unconvincing as a hitter. Herman came in as a technical consultant and served as a double for Cooper in long shots of Gehrig hitting.69

As Herman grew older, his playing time with the Stars decreased. A growing family and outside business interests gradually captured more of his attention. By 1940 he and Ann had four children: Charles Robert, Donald Edward, Jack Douglas, and Dorothy Virginia. The family lived in Glendale, where Babe was involved in numerous commercial endeavors.

Although Herman’s occasional misadventures on the field had engendered the image of a buffoon or simpleton, he was anything but. Keen in the ways of finance, he proved a solid negotiator in baseball and usually obtained top dollar for his services. Those skills transferred to the business world.

He was active in the local real estate market with his father-in-law and owned several properties in Glendale. Cobb’s Brown Derby restaurants – featuring the Cobb salad – fueled demand for another of Babe’s ventures. Casey Stengel, a knowledgeable businessman himself, was once asked his opinion of Herman. “They called him dumb. In the late 1930s he started a turkey farm near Glendale, and he sold his birds to the Brown Derby and other restaurants. The first year he had the farm President Roosevelt proclaimed two Thanksgivings.”70 Herman also had an orange grove and raised avocados.

Although Herman was successful in business, he never severed his ties with baseball. After hitting .346 for Hollywood in 1944, Herman retired – or thought he had. But World War II made qualified ballplayers scarce. In mid-summer 1945, Brooklyn was involved in a pennant race. General manager Branch Rickey asked Herman, then 42 and eight years removed from the majors, if he would like to join the team as a pinch-hitter. Babe and his family thought it a good idea and Rickey bought his contract from the Stars.

When word came out that Herman was rejoining Brooklyn, Tommy Holmes, longtime sportswriter for the Eagle, noted, “I suppose at this late date it is useless to replace fiction with fact and convince anybody that, in his six years as a colorful Dodger regular, Herman was never hit on the head.”71

In his first game back, on July 8, Herman pinch-hit at Ebbets Field with the Dodgers behind 6-2. With a runner on third, he singled off the right-field wall to drive in a run, then tripped and fell rounding first, to the amusement of fans and sportswriters. The “Old Herman” was back. While the incident became part of his legend, lost in the hilarity was that he singled off Red Barrett of the Cardinals, the best pitcher in the National League that year, winner of 23 games. It came in a game where St. Louis was fighting to close a 2½ game gap on the front-running Dodgers.

A few days later, Herman homered in a game against Pittsburgh. His pinch-hit single on September 9 at Cincinnati was his last major league hit. A week later he grounded out in a loss to the Cubs at Wrigley Field. He was hitting .265 and had played just seven innings in the field. The next day he was hit on the knee by a line drive during batting practice and never appeared in another game as Brooklyn faded to third place. When proceeds from the World Series were disbursed, his teammates voted Herman a $350 half-share.72

Babe Herman’s major league career ended with a .324 batting average and a .532 slugging mark based on 1,818 hits (with 399 doubles, 110 triples, and 181 home runs). Combining his major and minor league records, Herman amassed 3,363 hits, 303 home runs and a .329 average – not bad for someone whose father thought he should have become a contractor.

Although done as a player, Herman stayed connected with baseball over the next few decades, primarily as a scout. His wife Ann encouraged him: “My wife was the one who made it plain to me. “Floyd, turkey ranching is all right in the winter, but you couldn’t stand it as a 12-month proposition. You’ve played baseball too long to be interested or happy in anything else. And she was right.”73At various times he scouted for the Pirates, Phillies, Mets, Yankees and Giants. He is credited with signing several players who went on to the majors including Wally Westlake, Ed Fitzgerald, Vern Law, and Paul Blair.

Herman was once asked how he evaluated a prospect. “First of all the kid has got to catch your eye. He has to have that certain something, a touch of class, maybe. It’s like choosing a necktie or an automobile – you pick out a certain one from the bunch because you like it.”74 Along the way he coached for Pittsburgh in 1951 and managed the Bakersfield Bears of the California League for the last part of the 1957 season before he left baseball for good in 1964.

Herman’s son Don got Babe interested in growing orchids. This pursuit led him to become president of the Orchid Society of Southern California. Herman cultivated an award-winning strain, “Rajah’s Ruby,” as well as “Babe’s Baby,” so named by Ann because Babe spent so much time nursing it to maturity.75 He played golf to a nine handicap, collected stamps and coins, and traveled with Ann.

Sons Robert and Don graduated from the University of Southern California and daughter Dorothy from California, Berkeley. Robert became an assistant to Sir Rudolph Bing at the Metropolitan Opera and general manager of the Greater Miami Opera. Besides his interest in orchids, Don taught at Herbert Hoover High School. Dorothy married and continued to live in the area. The family lost son Jack, who had gone into sales in Arizona, to a premature death in 1970.

Babe was active in numerous local organizations, including Kiwanis, the Glendale Old Settlers organization, and the Glendale Chamber of Commerce. He was honored for his service to the community; a local diamond was renamed “Babe Herman Field” in recognition of his contribution to the sport.76

Baseball remembered Babe. He regularly participated in Old Timers’ games and Brooklyn Dodger fans selected him to their informal hall of fame. When Herman visited New York in 1981, the New York Baseball Writers recognized him with a “You Could Look It Up” award for his playing achievements.77 The Los Angeles Dodgers organization routinely included him in events honoring past players.

But baseball’s supreme honor, enshrinement in Cooperstown, eluded him. He had received a few votes in the ’40s and ’50s, never more than 6% in any one year. When interviewed about his Hall of Fame prospects, Herman ranged from indifference to belief that he should be chosen.78 Often these interviews conveyed his impression that he was left out because of negative press. “I guess there are two legends that have kept me out of the Hall,” he said in an interview with Maury Allen in 1983.79

The three-men-on-third episode routinely forced Herman into patient explanations – likewise for being “hit on the head by a fly ball.” And it wasn’t enough that Herman tripped past first base after singling on his return to the Dodgers in 1945. A 1971 article had Babe tagged out after falling down, when in fact he eventually scored.80 Ultimately, though, selection rested with the Hall’s Veterans Committee. They never called.81

In 1986 Babe was asked to throw out the first pitch at the Dodgers’ home opener. Despite a series of strokes beginning in 1984, he wanted to do it. Babe went into his den, picked up a ball – and dropped it. Ann informed the Dodgers he could not honor their request. Babe passed away on November 27, 1987, a few weeks after he and Ann had celebrated their 64th wedding anniversary.82 He was 84 years old.

Floyd “Babe” Herman was one of baseball’s most colorful characters. His hitting captured fans’ attention, his occasional mishaps endeared him to – or infuriated – fans, his holdouts sold newspapers. His reputation went beyond the playing field. Several of the “daffy” comments attributed to him evoke the more recent “Yogi-isms” associated with Yogi Berra, which often originated with others, notably Berra’s close friend Joe Garagiola.83 Even classic lines such as a young woman’s comment to Babe, “My, but you look cool, Mr. Herman,” and his reply, “You don’t look so hot yourself,” are now credited to Berra. The truth more likely is that this retort existed well before Herman or Berra.84

But whatever debate may have lingered about his Hall of Fame credentials mattered little to Babe in his later years. He was content. His family, his community involvement, and his hobbies gave him an inner satisfaction that surpassed any need for public acclaim. He had always set his own course, in both baseball and life. And that course was eminently successful – one many would envy.85

Acknowledgments

The author would sincerely like to thank Stephen Rice for his dedication to making the varied facets of Herman’s life and baseball career known and his extensive preliminary research that greatly aided in completing this biography. The author also appreciates Rory Costello’s and Jack Zerby’s editing assistance.

Sources

Alexander, Charles C. Breaking the Slump: Baseball in the Depression Era (New York: Columbia University Press, 2002).

Barra, Allen. Yogi Berra, Eternal Yankee (New York: W. W. Norton & Co., 2009).

Bradlee, Ben Jr. The Kid: The Immortal Life of Ted Williams (New York: Little Brown & Co., 2013).

Curran, William. Big Sticks: The Phenomenal Decade of Ruth, Gehrig, Cobb and Hornsby (New York: Harper Perennial/HarperCollins, 1990).

Dean, Bill. Baseball Myths: Debating, Debunking, and Disproving Tales From the Diamond (Toronto: The Scarecrow Press, 2012).

Golenbock, Peter. Bums: An Oral History of the Brooklyn Dodgers (New York: G. P. Putnam’s Sons, 1984).

Holmes, Tot. Brooklyn’s Babe: The Life and Legend of Babe Herman (Gothenburg, NE: Holmes Publishing, 1990).

Honig, Donald. Baseball America: The Heroes of the Game and the Times of Their Glory (New York: Macmillan Publishing Co., 1985).

James, Bill. The Politics of Glory: How Baseball’s Hall of Fame Really Works (New York: Macmillan Publishing Co., 1994).

Kavanaugh, Jack and Norman Macht. Uncle Robbie (Cleveland: Society for American Baseball Research, 1999).

Lowry, Philip J. Green Cathedrals: The Ultimate Celebration of Major League and Negro League Ballparks (New York: Walker & Company, 2006).

O’Neal, Bill. The Texas League: A Century of Baseball (Austin: Eakin Press, 1987).

___. The Pacific Coast League, 1903-1958 (Austin, Eakin Press, 1990).

Allen, Maury. Bylined articles, New York Post, March 3, 1983, and November 30, 1987.

Bank, Dick. “The Other Babe Will Always Be Remembered,” Los Angeles Times, December 5, 1987.

Burr, Harold C., “Tom Burns, Old Robin Gardner, Likes New Team,” Brooklyn Daily Eagle, July 8, 1928.

Costello, Kenneth W. “Johnny Butler Deal Still Bringing ‘Em In,” The Sporting News, February 18, 1926.

Dyer, Mike. “Former Dodger Slugger: I Belong In Hall of Fame,” The Daily Star, November 7, 1979.

Finch, Frank. “Hit .381 and .393, Yet Finished Second!” The Sporting News, March 11, 1953.

Foster, John B. “Styles Changes in Ball as Experiment Yet to be Tested,” The Sporting News, February 12, 1931.

Hinton, L. D. “Crackers Put In a Kick At Point Where It Helps A Lot,” The Sporting News, July 5, 1923.

Holmes, Tommy (Thomas). Numerous bylined articles, Brooklyn Daily Eagle, April 15, 1926, through July 9, 1945.

___. Bylined articles, The Sporting News, April 3, 1930, through June 17, 1930.

Ostler, Scott. “Remembering Babe Herman,” Los Angeles Times, December 5, 1987.

Rice, Thomas H. Bylined articles, The Sporting News, May 27, 1926, through February 27, 1930.

Spink, J. G. Taylor. “Three and One, Looking Them Over,” The Sporting News, January 11, 1940.

Swope, Tom. Bylined articles, The Sporting News, February 25, 1937.

White, Deacon. “Bad Breaks Can Not Keep Gleichman Down,” The Sporting News, June 6, 1921.

York, Frank. “Seeking Pitchers Gets Case of ‘Convention Feet,’” The Sporting News, December 18, 1930.

Brooklyn Daily Eagle, June 17, 1932; October 1, 1945.

Chicago Daily Tribune, May 5, 1926.

The Sporting News, June 5, 1924, January 15, 1925, January 14, 1926, December 18, 1930, March 11, 1953.

Weatherby, Charles. “Red Killefer,” SABR Biography Project, sabr.org

Zerby, Jack. “May 25, 1935: Ruth smashes 3 homers in final hurrah,” SABR Games Project, sabr.org.

Ancestry.com

Baseball-Reference.com

Retrosheet.org

QuoteInvestigator.com

1940 United States Federal Census.

Excerpts from Babe Herman file, Giamatti Research Center, National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum, Cooperstown, NY.

Scribner Encyclopedia of American Lives, Vol. 2, 1999.

Author’s e-mail correspondence with Dave Smith, SABR/Retrosheet, February 19, 2015.

Notes

1 Tot Holmes, Brooklyn’s Babe; The Life and Legend of Babe Herman, (Gothenberg, Nebraska, Holmes Publishing, 1990, 1. Although a thorough biography of Herman, Holmes’s book has the drawback of insufficient documentation for much of the material. For clarity, it must be noted that two men named “Holmes” chronicled Babe Herman’s career: Tot Holmes, his biographer, and Tommy (Thomas) Holmes, a sportswriter for the Brooklyn Daily Eagle and stringer for The Sporting News, whose coverage spanned 1926-45.

2 Thomas Holmes, “Hit on the Line,” Brooklyn Daily Eagle, May 26, 1930, 20.

3 Holmes, Brooklyn’s Babe, 3.

4 Holmes, “Hit on the Line,” 3. Tot Holmes, Brooklyn’s Babe, says Herman was offered $175.

5 Deacon White, “Bad Breaks Can Not Keep Gleichman Down,” The Sporting News, June 6, 1921, 3.

6 Ibid., 7, and Gene Karst, Cincinnati Baseball Club: Babe Herman, undated in Herman’s Hall of Fame File.

7 “Babe Herman, 84 Former Outfielder With the Dodgers,” New York Times, November 30, 1987, B13.

8 His slugging average during this time period was .522.

9 Holmes, Brooklyn’s Babe, 8.

10 Frank Finch, ‘Hit .381 and .393 – Yet Finished Second!” The Sporting News, March 11, 1953, 13

11 “Red Sox Gent Another Possible Ruth in Deal,” The Sporting News, October 26, 1922, 6.

12 Holmes, Brooklyn’s Babe, 13

13 Ibid., 14

14 J. G. Taylor Spink, “Three and One, Looking Them Over With J. G. Taylor Spink, The Sporting News, January 11, 1940, 4.

15 Entering the 1924 season the Fort Worth Panthers had won five straight Texas League Championships. They won in 1924 and 1925 as well. Bill O’Neal, The Texas League: A Century of Baseball, (Austin, TX: Eakin Press, 1987), 338-339.

16 Holmes, Brooklyn’s Babe, 16

17 Between San Antonio and Little Rock, Herman played only 90 games, hitting a composite .326.

18 Charles Weatherby, “Red Killefer,” SABR Baseball Biography Project, http://sabr.org/bioproj/person/1939cba2

19 “Killefer Believes He Has Stronger Team,” The Sporting News, January 15, 1925, 2

20 “Wade Killefer Getting Ready To Re-paint Seattle Indians,” The Sporting News, January 14. 1926, 7.

21 “Floyd Caves (Babe) Herman”, undated, unidentified publication in Herman’s Hall of Fame file.

22 Jack Kavananagh and Norman Macht, Uncle Robbie, (Cleveland OH, Society for American Baseball Research (SABR), 1999), 139, 157.

23 Kenneth W. Costello, “Johnny Butler Deal Still Bringing ‘Em In,” The Sporting News, February 18, 1926, 3

24 “Minneapolis Sends Herman Back,” The Sporting News, April 15, 1926, 1.

25 Kananagh and Macht, Uncle Robbie, 147.

26 Between 1922 and 1929 Brooklyn finished sixth every year except for a near pennant-winning effort in 1924.

27 “Fournier Hurt As Robins Beat Braves By 3 To 2,” Chicago Daily Tribune, May 5, 1926, 25.

28 Thomas H. Rice, “Inevitable Happens to Brooklyn Robins,” The Sporting News, May 27, 1926, 3.

29 Tommy Holmes, “Brooklyn Fans Are Already Attracted by Herman,” Brooklyn Daily Eagle, May 26, 1926, 24.

30 Much was written about Herman’s ability to hit to all fields; some suggested he was a place hitter. Herman denied it, “Place hitter? What is that? I just take a cut and let the ball go where it will. I aim to hit each ball I swing at with my bat on a level [plane]. The way the ball is pitched to me determines where the ball will go if I hit it. Thomas Rice, “Uncle Robbie Can’t Quite “Get” His Club,” The Sporting News, June 24, 1926, 1.

31 At the time of Herman’s effort, it was thought Cuyler had the longest streak for consecutive hits. In 2009 it was discovered that Johnny Kling had amassed 12 straight hits in 1902. Source: http://bleacherreport.com/articles/934773-ranking-the-most-unbreakable-mlb-player-streaks-and-consecutive-game-records/page/20

32 Bill Dean, Baseball Myths: Debating, debunking, and disproving Tales from the Diamond, (Toronto: The Scarecrow Press, 2012), 61-63. Dean’s write-up on the play includes five different descriptions of how the play unfolded, including one by Herman.

33 Tommy Holmes, “Freak Play in First Game Features as Robbie’s Men Wallop Braves Twice, “Brooklyn Daily Eagle, August 16, 1926, 16.

34 http://www.baseball-reference.com/bullpen/Babe_Herman

35 Tommy Holmes, “Babe Herman, Latest to Uplift the Drama, Had One Great First Year,” undated clipping in Herman’s Hall of Fame file.

36 “Herman No Babe in Busine$$” unidentified publication in Herman’s Hall of Fame file.

37 Thomas Rice, “Good Can Balance Bad In The Robins,” The Sporting News, April 21, 1927, 3.

38 Holmes, Brooklyn’s Babe, 41, 47, 49.

39 Thomas Rice, “Robins Not Placed As Season Opens,” The Sporting News, April 12, 1928, 3.

40 Holmes, Brooklyn’s Babe, 65, 66.

41 Bissonette’s 25 home runs in 1928 set a new record for home runs by a rookie. Wally Berger of the Braves bested it two years later with 38.

42 “Pick A Clown – Could He Outdo Babe Herman?” 1971, Unidentified publication in Herman’s Hall of Fame file.

43 Maury Allen, “Babe Herman, beloved ex-Dodger, dead at 84,” New York Post, November 30, 1987, 71.

44 Holmes, “Bressler’s Observation Halts Ring’s Spitball And the Phillies Return,” Brooklyn Daily Eagle, June 19, 1928, 24.

45 Holmes, “Two Victories Today May Shove Brooklyn Back Among Leaders, Brooklyn Daily Eagle, June 28, 1928, 24.

46 Thomas Holmes, Development of 1929 Regulars is Beam of Light Through Clouds, Brooklyn Daily Eagle, August 5, 1928, 42.

47 Harold C. Burr, “Tom Burns, Old Robins Gardner, Likes New Team,” Brooklyn Daily Eagle, July 8, 1928, 34

48 Holmes, Brooklyn’s Babe, 81.

49 Holmes, Brooklyn’s Babe, 95.

50 Thomas Rice, “Vance Signs, Takes Slice in His Salary,” The Sporting News, February 27, 1930, 1.

51 Thomas Holmes, “Herman Signs for $15,000 After All,” The Sporting News, April 3, 1930, 1 and Tot Holmes, Brooklyn’s Babe, 100.

52 Thomas Holmes, “Robins Put in Race By Mended Cripples,” The Sporting News, May 29, 1930, 1.

53 Thomas Holmes, “”His Bat Aids Robins’ Flight,” The Sporting News, June 12, 1930, 1.

54 Thomas Holmes “Phelps and Herman Upset Cardinals, While Lineup Changes Help,” Brooklyn Daily Eagle, June 17, 1930, 22

55 During the winter of 1930 a discussion took place at the major league meetings on the baseball manufacturing process. No action was taken then about curtailing offense, but several months later it was announced that balls would be changed for the 1931 season. The National League opted for a ball with a heavier thread, the leather a bit heavier. The American League would use balls with a raised thread. These changes were considered insignificant at the time, but in practice, hitting decreased. The 1930 NL average of .303 dropped to .277 and runs scored dropped more than 20 percent. League leaders in 1930 all fell off considerably. Terry dropped from .401 to .349; O’Doul, .383 to .336; Chuck Klein .386 to .337, Freddie Lindstrom from .379 to .300, and Herman, .393 to .313. “Listening In at Majors’ Gabfest,” The Sporting News, December 18, 1930, 3; John B. Foster, Foster Styles Changes in Ball As Experiment, Yet to Be Tested,” The Sporting News, February 12, 1931, 2. In 1934 a uniform ball was adopted for both leagues. William Curran, Big Sticks; The Phenomenal Decade of Ruth Gehrig, Cobb and Hornsby, (New York: Harper Perennial, A Division of HarperCollins Publishers, 1990), 280.

56 As of 2015, the only other is Aaron Hill (2012)..

57 Harry Heilmann hit 19 in the offense-packed 1930 season, impressive considering Redland Field (renamed Crosley Field in 1934) was one of the most spacious parks in baseball.

58 “Who’s Sorry Now,” Brooklyn Daily Eagle, June 17, 1932, 22.

59 In 1961 an article on Herman in The Sporting News recounted his adventures in baseball, one of which involved hitting two triples in a game at Wrigley Field and subsequently being called out after each one for leaving third base prematurely in sacrifice fly situations. Herman hit two triples in a game seven times in his career, including once at Wrigley Field on June 7, 1933. Neither the 1933 game account nor accounts of any of the six other two-triple games mention these supposed gaffes—evidence of the “stories” about Herman.

60 Herman began working out in California prior to spring training. On one occasion he was taking batting practice prior to a scheduled doubleheader between local high school teams, one of which was Herbert Hoover High. A young Ted Williams, who played for Hoover, was impressed. “Oh, I wish I had power like that. I wish I was that big and strong.” Williams then proceeded to hit two balls in the subsequent game farther than Herman. Ben Bradlee Jr., The Kid: The Immortal Life of Ted Williams, (NY: Little Brown & Company, 2013), 65.

61 Holmes, Brooklyn’s Babe, 195.

62 Jack Zerby, “May 25, 1935: Ruth smashes 3 homers in final hurrah,” SABR Games Project, http://sabr.org/gamesproj/game/may-25-1935-ruth-smashes-3-homers-final-hurrah.

63 Hafey missed the entire 1935 season due to illness. TSN captured Herman’s change in status, “Babe Herman’s Return To Reds Sets Speedy Reverse In Values; $65,000 Player in 1932 Taken On Waivers.”

64 Holmes, Brooklyn’s Babe, 197-198.

65 His 71 RBIs were just three behind team leader Kiki Cuyler who played in 25 more games.

66 Ironically, his manager for part of the season was Hank DeBerry, who had scored the winning run on Herman’s infamous “doubling into a double play” incident.

67 Bill O’Neal, The Pacific Coast League, 1903-1958, (Austin TX, Eakin Press, 1990), 206-207.

68 Dick Bank, “The Other Babe Will Always Be Remembered,” Los Angeles Times, December 5, 1987, http://articles.latimes.com/1987-12-05/sports/sp-6143_1_babe-herman-hollywood-stars-los-angeles.

69 Holmes, Brooklyn’s Babe, 214-15.

70 “The Babe Herman Legend,” Unidentified publication in Herman’s Hall of Fame file.

71 Tommy Holmes, “Babe Herman Plays An Incredible Role,” Brooklyn Daily Eagle, July 5, 1945, 8.

72 “Dodgers Cut Up 45’ Melon Generously,” Brooklyn Daily Eagle, October 1, 1945, 11

73 Tom Meany, “Babe Herman Has an Answer To “What’s in It for Me?’ Unidentified publication in Herman’s Hall of Fame file.

74 Finch, ‘Hit .381 and .393 – Yet Finished Second!” The Sporting News, March 11, 1953, 11.

75 Holmes, Brooklyn’s Babe, 228.

76 Holmes, Brooklyn’s Babe, 229.

77 Red Smith, “Belated Wishes,” The New York Times, January 30, 1981.

78 See, for instance, Scott Ostler, “Remembering Babe Herman,” Los Angeles Times, December 1, 1987, D1 and Mike Dyer, “Former Dodger slugger: I belong in Hall of Fame,” The Daily Star, November 7, 1979, 19, for several perspectives on Herman’s interest in the Hall of Fame.

79 Maury Allen, Whatever Happened to…Babe Herman: darling of Flatbush, New York Post, March 3, 1983, Herman’s Hall of Fame file.

80 “Pick a Clown – Could He Outdo Babe Hoiman?” 1971 San Diego Scorebook, Herman’s Hall of Fame file.

81 While Herman’s sometimes-zany play – real or imagined – did not help his cause in being selected to Cooperstown, his chances for induction were at best, marginal. Herman’s major league career, spanning eleven full seasons, was relatively short by inductee standards. Unlike his peers Hornsby, Ott, Terry, and Waner, he never dominated in any major offensive category, another test of potential inductees. Herman’s peak seasons of 1929-30 coincided with the zenith of major league offensive productivity, somewhat qualifying his performance. And finally, an intangible not within his control – Herman never played on a pennant-winning team. For a more complete examination of Herman’s qualifications, see Bill James, “The Politics of Glory: How Baseball’s Hall of Fame Really Works,” (New York: Macmillan Publishing Company, 1994) and Jim Hamilton, “This ‘SHOW’ probably won’t make Hall of Fame”, June 4, 1996, Herman’s Hall of Fame file.

82 Ostler, “Remembering Babe Herman.”

83 Allen Barra, Yogi Berra, Eternal Yankee, (New York: W. W. Norton & Company, 2009), xxxiii.

84 Quote Investigator.com, http://quoteinvestigator.com/2012/11/23/you-look-cool/.

85 Ostler, “Remembering Babe Herman.”

Full Name

Floyd Caves Herman

Born

June 26, 1903 at Buffalo, NY (USA)

Died

November 27, 1987 at Glendale, CA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.