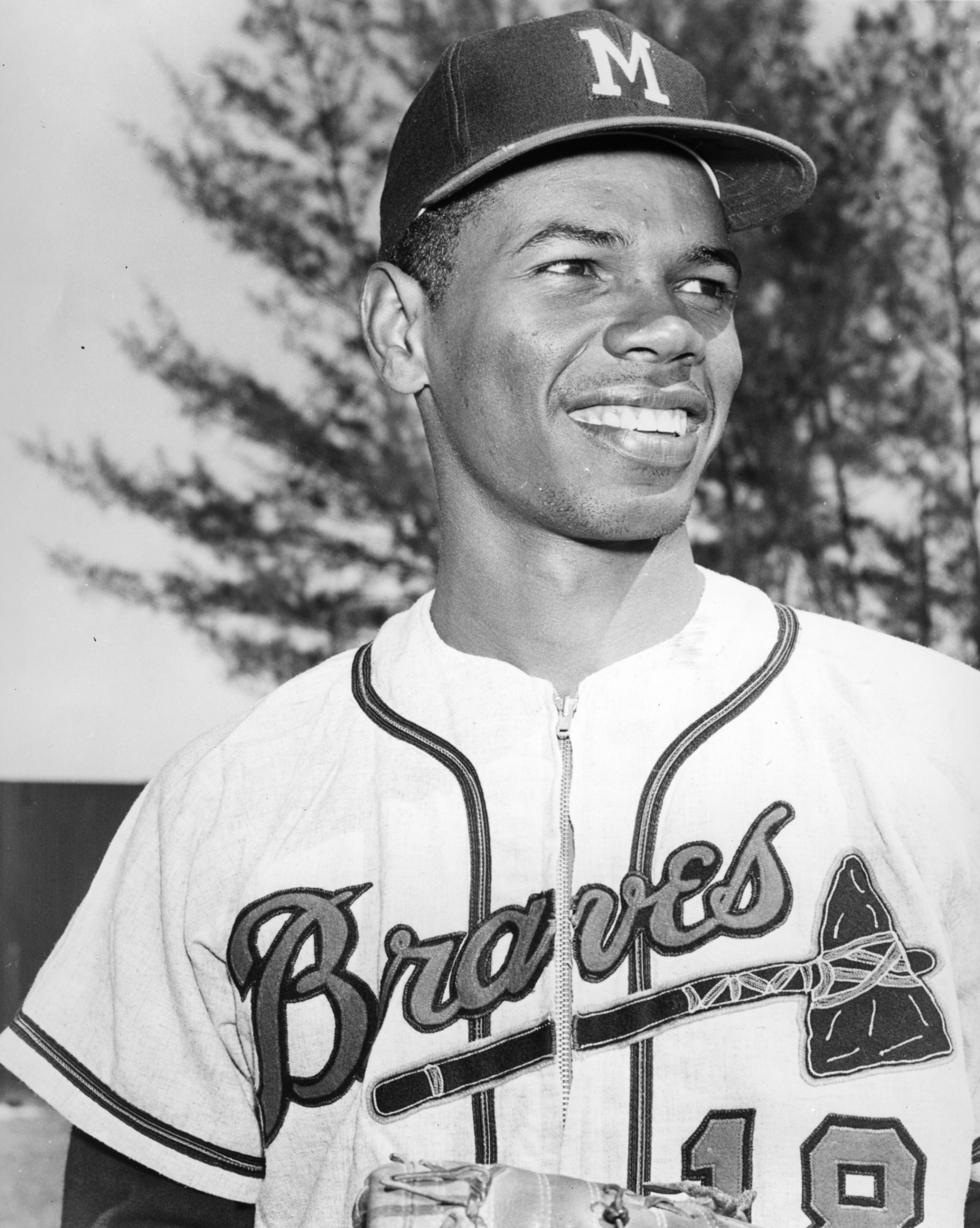

Felix Mantilla

Versatility is the best word to describe Felix Mantilla’s 11-year career, in which he won a world championship with the 1957 Milwaukee Braves, appeared in the All-Star Game, and played every position other than pitcher and catcher. Felix (Lamela) Mantilla was born on July 29, 1934, in Isabela, a town in the northwest corner of Puerto Rico. His parents were Navidad, of Taino Indian and Spanish descent, and Juan, of African descent. Juan drove a taxi and Felix said that the family “never had much money, but you know, it never seemed to bother us.”1

Felix had two younger sisters, Judith, who graduated from the Interamerican University in San German, Puerto Rico, and Felicita, who became a police officer with the Puerto Rican Police Department.

Puerto Ricans love baseball. There are many different levels of leagues in the country. Mantilla began playing baseball when he was 9 years old, competing in police-sponsored leagues. He was such an excellent third baseman that he was promoted to what Puerto Ricans call Class A ball, playing with older teammates. After a year he was promoted to Arecibo, a city about 45 miles from Isabela to compete in a Class AA league. Later, he became a player on the Puerto Rican National team. Mantilla also played high-school sports, competing in softball, baseball, and track, running in the 100-meter event. One of Mantilla’s greatest accomplishments was playing for the Puerto Rican National team that won the Amateur World Series in 1951, defeating Cuba 6-5.

At Caguas in the Puerto Rican league, Mantilla played for manager Luis Olmo, who spent six years in the major leagues with the Brooklyn Dodgers and Boston Braves. Olmo sent Mantilla to the Boston Braves’ minor-league camp at Myrtle Beach, South Carolina. “I always wanted to be a big leaguer,” Mantilla said. “I guess I looked pretty good at Caguas, so the (team) sent me to the Braves for a trial. They had a kind of working agreement.”2 Braves scout Hugh Wise was so impressed with Mantilla that he offered him a contract. Mantilla remembered signing the final contract and said, “It was for (a bonus of) $400, which seems paltry today, but back then, I can assure you, it was a fortune. Of course I grabbed it and signed.” Asked how he spent his bonus, Mantilla said, “Are you kidding? My mother got it.”3

Before leaving for the camp, Mantilla got a warning from his high-school principal. “The principal knew that I was going to the United States, and he told me, Felix, you might have some problems when you get to the US. You are going to go from San Juan to Miami, then from Miami to Myrtle Beach. Sometimes if you ride a bus, to avoid problems you have to sit in the back.”4 This was all new to Mantilla, since he didn’t have to go through this in Puerto Rico, but he was grateful for the advice, and having about ten Puerto Rican players accompany him on the trip made it a little easier.

The Myrtle Beach complex had four baseball diamonds, and in the middle was a tower for the coaches to observe. One day Mantilla was taking batting practice with the Class C Eau Claire team, then “It was the seventh inning of the [Class B] Evansville game, and they needed a third baseman. They sent me over, and I stayed with Evansville. It was a break for me.”5

Another barrier Mantilla had to overcome was being able to communicate in English. “They wanted me to go for English lessons in Evansville, and I went to school, but they talked too fast,” he said. “I picked up my English at the movies, Westerns. There were three or four movie theaters, but there was only one where colored people could sit in the balcony and watch.”6

At Evansville (Three-I League) Mantilla played for manager Bob Coleman, of whom he said, “He liked me, and I liked the guy. He gave me a chance to play.”7 Mantilla had an impressive 1952 season, playing shortstop and batting .323, and was named the Three-I League’s rookie of the year and its All-Star shortstop.

In the offseason, Mantilla played winter ball for Caguas in the Puerto Rican league, where one of his teammates, second baseman Henry Aaron, was moved to the outfield where, Mantilla said, “It seemed he was more at ease than he was at second.”8

For 1953 Mantilla was promoted to the Jacksonville Braves of the Class A South Atlantic League. He, Aaron, and Horace Garner integrated the team for the first time and helped as it finished in first place. (The Braves lost in the playoff finals.) Mantilla batted .278 and Aaron led the league in batting (.362). “Jacksonville was real bad. I’m talking about 1953, not now,” Mantilla said. “They wouldn’t boo you because you were playing bad; it was just because you were colored.”9

Again he spent the offseason playing for Caguas, helping the team capture the Puerto Rican title. For 1954 “They were going to move me to what I think was the Atlanta Crackers at the time, but I wasn’t too receptive to that idea, so they moved me to the Triple-A team in Toledo. … It was pretty tough there too, though.”10 Mantilla batted.273 and hit 16 home runs. In a Memorial Day doubleheader sweep at Louisville, he accounted for eight of his team’s 12 runs, belting two triples in the opener and a three-run homer in the nightcap. He had a 23-game hitting streak during the season. Still only 20 years old, Mantilla also spent the 1955 season at Toledo, batting .275.

At Milwaukee’s spring training in Bradenton, Florida, in 1956, Mantilla impressed manager Charlie Grimm, who said he had “one of the best pair of hands I ever saw.”11 For the start of the season he was sent to Sacramento of the Pacific Coast League, but was called up on June 15 to provide backup for shortstop Johnny Logan, who was in a batting slump. He made his major-league debut on June 21 against the Pittsburgh Pirates at Forbes Field, replacing Logan at shortstop. In his first at-bat he popped out to the second baseman. He made his first start on July 1, against the Chicago Cubs in the second game of a doubleheader at Wrigley Field, playing third base and leading off. He went hitless in four at-bats. Mantilla said he was “kind of nervous, but after one inning, I lost my nervousness.”12 He stayed with the Braves the rest of the season, batting. 283 in 53 at-bats.

Mantilla earned a spot on the Braves’ 1957 roster, impressing manager Haney, who observed that “At third, he’s as quick as a cat and has that arm. He can make the pivot on the double play at second.”13 After the newly acquired Red Schoendienst was injured, Mantilla briefly filled in for him.

Mantilla suffered a bruised chest in a collision with outfielder Billy Bruton on July 11 and was sidelined for 18 days. (Bruton was sidelined for the rest of the season.) Mantilla returned to duty on July 29 at County Stadium with a pinch-hit bases-loaded walk that ended a wild extra-inning contest against the New York Giants. The come-from-behind victory kept the Braves in first place by a half-game over St. Louis. In mid-August he filled in at shortstop for Logan, who was recovering from an infected shinbone.

Playing in Milwaukee was an unbelievable experience, Mantilla said. “I remember in spring training, Humberto Robinson said, ‘When you get to that city you won’t believe it.’ I didn’t have any idea. I thought maybe it was like Puerto Rico where people got kind of goofy. But when I came here it was a different thing. When I was in the house I could hear at the back door someone was leaving milk. They used to bring a gallon every day for free. There was beer out there. … We used to get Wisco 99 gas and a car from Rank and Son (a Milwaukee car dealer). I had never seen a place like this before. And the fans. If you lost a game they didn’t boo you. Coming from a Latin country, when you started losing games you had to watch your back. The park was crowded every day. It was a good feeling every time you went to the ballpark. With the fans behind you, you can’t lose.”14

Mantilla played in four games in the Braves’ World Series victory over the Yankees. As a pinch-runner he scored the tying run in Game Four. He replaced second baseman Schoendienst (pulled muscle) in Game Five and started Games Six and Seven at Yankee Stadium. In Game Seven. Being on the field for the final out in Game Seven “was the greatest feeling of all time,” he said. Mantilla called the World Series victory one of his memorable accomplishments.15

Mantilla demonstrated his versatility during the 1958 season, starting 27 games in center field, filling in for the injured left fielder Wes Covington, and also filling in at second base, shortstop and third base. One of his biggest disappointments was the Braves’ loss to the Yankees in their World Series rematch, when Milwaukee squandered a three-games-to-one advantage.

At Caguas after the 1958 season, manager Ben Geraghty moved Mantilla from shortstop to second base to help facilitate his probable move to second base to replace tuberculosis-stricken Schoendienst in 1959. As it turned out, Mantilla played 60 games at second, one of six players to fill in for Schoendienst.

In Harvey Haddix’s historic pitching feat on May 26, Mantilla became the Braves’ first baserunner when he reached first on a throwing error by Pirates third baseman Don Hoak to lead off the 13th inning. Mantilla went to second base on Eddie Mathews’ sacrifice and scored the winning run on Joe Adcock’s blast. But the season ended on a sour note for the Braces, who were swept by the Los Angeles Dodgers in two games in a best-of-three pennant playoff. Mantilla started Game Two at second base but switched to shortstop after Johnny Logan was injured in the seventh inning. In the 12th inning with two out and Dodgers on first and second, Carl Furillo hit a grounder up the middle. “When the ball came over the pitcher’s head,” said Mantilla, “I thought I could pick it up and step on the bag. When I got it, I was past the bag and I knew I had to throw to first. I never thought of not throwing to first because I could’ve gotten him with a good throw. I was off balance when I threw, and that’s why it bounced away.”16 Gil Hodges scored on the play, giving the Dodgers the pennant. Braves manager Fred Haney said of Mantilla, “He did the only thing he could, he didn’t make a bad play. He was lucky to stop the ball at all.”17

The 1960 season was another carousel at second base. The Braves were hoping for a return of Schoendienst after his bout with tuberculosis, but the 37-year-old struggled at the plate. Chuck Cottier and Mel Roach also played second base. Mantilla had 148 at-bats with a .257 average and played mainly at second base and shortstop in 63 games.

During the offseason, the Braves changed the makeup of their infield. They acquired Roy McMillan from the Reds to share duties at shortstop with Johnny Logan, and Frank Bolling from the Tigers to play second base. The handwriting was on the wall and Felix knew it, commenting, “They use me in 45 games, and then I see a newspaper got a list of the guys who might go in the draft, Bob Boyd, Al Spangler and me.”18 On October 10, 1961, Mantilla was selected by the brand-new New York Mets in the National League expansion draft.

Given the opportunity to play regularly for the Mets in 1962, Mantilla responded by batting .275 (second highest on the team) in 141 games. The Mets had a horrible season, going 40-120. It was a difficult transition going to a losing team; Mantilla said, “I don’t think anyone dreamed the team was going to be that bad. On paper, it didn’t look that bad.” Casey Stengel, he said, “would bring out the lineup to the umps before the game, then would go back into the dugout and go to sleep. I guess he couldn’t bear watching.”19

After the season Mantilla was traded to the Boston Red Sox for infielder Pumpsie Green, pitcher Tracy Stallard, and shortstop Al Moran. Red Sox manager Johnny Pesky was pleased with the acquisition of Mantilla. “I saw him in 1955 when I was coaching at Denver and he looked like a fine shortstop,” Pesky said. “They say he plays a good third and second base. I could use Mantilla in three different positions.”20 Mantilla loved playing in Fenway Park; “it was a great park to see the ball real well. Everything seemed like it was green.”21 While playing for Boston he lived in the nearby Kenmore Hotel.

Mantilla didn’t get much playing time during the 1963 season, appearing in just 66 games, but he batted .315. When Ed Bressoud suffered a severe heel sprain and bruise, Mantilla filled in for him, and he began playing second base the last two weeks of the season.

In 1964 he played more often (133 games), filling in at all the outfield positions and at second base, third base, and shortstop. Johnny Pesky had acknowledged before the season, “I should have used Felix Mantilla more (in 1963). He played well in the infield and outfield when I used him. …”22

Mantilla delivered a walkoff two-run, pinch-hit home run in the bottom of the ninth in a 5-4 victory over the Kansas City Athletics on May 23. It was only his second home run of the season. On May 31 he came through again, slugging a pinch-hit double in the ninth inning to beat the Minnesota Twins, 4-3. While replacing an injured Tony Conigliaro in the lineup, Mantilla blasted three homers in two games against the Cleveland Indians on June 27-28. The home run barrage continued and by August 15 Mantilla had 20 home runs.

What caused this sudden power surge? Cleveland manager Birdie Tebbetts, who had also managed Mantilla at Milwaukee, had a theory: “When he went to the Polo Grounds, it became necessary to pull the ball, that he developed a swing that lifted the ball up. It’s a swing that’s perfect for Fenway and almost every park in our league. He has become probably the most improved man in a career I ever saw.”23

Mantilla finished the season with 30 home runs in 425 at-bats, an amazing performance considering that he had clubbed only 35 home runs in his previous eight seasons in the majors. He drove in 64 runs, and batted .289. Not bad for a player who saw limited action the first month of the season. Mantilla was honored by the Boston Chapter of the Baseball Writers Association, which gave him the Comeback Player of the Year Award after the season.

Newly appointed Red Sox manager Billy Herman had big plans for Mantilla for the 1965 season, saying he planned to bat him in the fifth spot. “Felix hit 30 homers last year and I want him down where he can drive in the maximum number of runs,” Herman said.24 Mantilla came through with a big season, batting .289, driving in 92 runs, and blasting 18 home runs. He was picked as the American League’s starting second baseman for the All-Star Game, his only All-Star Game appearance, and went 0-for-2.

Mantilla spent the offseason working for the Milwaukee police department along with major leaguers Bob Uecker and Don Pavletich in a program instituted by Judge Robert Cannon to help curb juvenile delinquency. Just before the start of the 1966 Mantilla was traded to the Houston Astros for infielder Eddie Kasko. Mantilla had hurt his arm and shoulder during spring training, and he thought the Red Sox decided that this was a good time to move him. He was puzzled that Red Sox told him the trade was for youth but Kasko was two years older.

For the Astros, Mantilla spent most of the first month of the season on the disabled list, then batted .219 with 22 runs batted in in 77 games (151 plate appearances). In the Astros’ final game of the season, on October 2 against the Mets at Shea Stadium, Mantilla had a home run, a double, and three runs batted in what turned out to be his last major-league game.

After the 1966 season, Mantilla asked the Astros for his release, which was granted. He considered playing in Japan, but in February 1967 he signed with the Chicago Cubs, who were closer to his home in Milwaukee. While in spring training with the Cubs, Mantilla tore his Achilles tendon during a timing drill. He realized his career was over.

Mantilla played a few games for a team in Sherbrooke, Quebec, but his legs were hurting. The team’s manager was fired and Mantilla succeeded him and guided the team to a second-place finish. Mantilla wanted to continue as manager, but the ownership wanted a player-manager, Mantilla returned home to Milwaukee. He worked for the Boys’ Club in Milwaukee. A Little League team that competes in the southside of Milwaukee was named after him.

Mantilla has two children from his marriage on September 17, 1953, to Delores Berry, whom he met while playing at Jacksonville. Felix Jr. is a retired attorney and Jose is a retired banker. Mantilla has been married to Kay since 1981, and they reside in the northwest side of Milwaukee. They have five grandchildren. Mantilla said he loves retirement because he can do what he wants to do, when he wants to.25

On January 10, 2025, Mantilla died at the age of 90.

Last revised: Jan 11, 2025 (ghw)

Sources

In-person interviews with Felix Mantilla, November 3 and 8, 2012.

Milwaukee Journal

Milwaukee Sentinel

San Francisco Chronicle

The Sporting News

Baseball-Reference.com

Retrosheet.org

Baseball Hall of Fame Library: Player file for Felix Mantilla.

Notes

1 Jack Pearson, “The Kid from Puerto Rico decided he liked it here,” 50 Plus, May 2010.

2 Bob Wolf, “Mantilla Now Blocked by Logan at Shortstop but Has Bright Future,” Milwaukee Journal, April 1, 1956.

3 Pearson, “The Kid.”

4 Mantilla interview, 2012.

5 Vic Ziegel, “Mantilla Arrives,” Sport, August 1965.

6 Ziegel, “Mantilla Arrives.”

7 Mantilla interview, 2012.

8 Paul Green, “Felix Mantilla,” Sports Collectors Digest, July 19, 1985.

9 Ziegel, “Mantilla Arrives.”

10 Green, “Felix Mantilla.”

11 Bob Wolf, “Braves’ Talent Bin Overflowing With Nifty Kid Infielders,” The Sporting News, March 21, 1956.

12 Mantilla interview, 2012.

13 Cleon Walfoort, “Pennant Rides on ‘Felix the Cat,’ Now the Club’s Only Shortstop,” Milwaukee Journal. Undated article from the Mantilla file at the Baseball Hall of Fame library.

14 Mantilla interview, 2012.

15 Mantilla interview, 2012.

16 Mantilla interview, 2012.

17 “Crestfallen Mantilla Says He Was Off Balance,” San Francisco Chronicle, September 30, 1959.

18 Ziegel, “Mantilla Arrives.”

19 Pearson, “The Kid.”

20 Hy Hurwitz, “Wanted: Hungry Players, Pesky Tells Hub Hose,” The Sporting News, February 2, 1963.

21 Mantilla interview, 2012.

22 Pesky Will Return in ’64; Vows to Correct Mistakes,” The Sporting News, October 5, 1963.

23 Ziegel, “Mantilla Arrives.”

24 Larry Claflin, “Pleasant Surprise? Watch Morehead, Says Hub’s Herman,” The Sporting News, December 19, 1965.

25 Mantilla interview, 2012.

Full Name

Felix Mantilla Lamela

Born

July 29, 1934 at Isabella, (P.R.)

Died

January 10, 2025 at , ()

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.