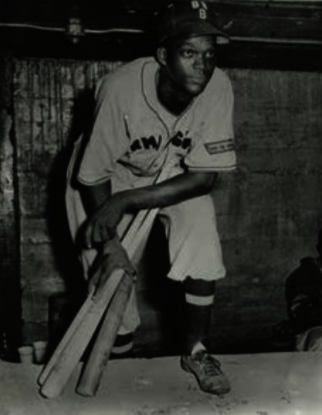

Piper Davis

On June 12, 1996, the Birmingham Barons returned to historic Rickwood Field after an eight-year absence for the first Rickwood Classic. Before the game with the Memphis Chicks, the team honored former Baron Walt Dropo and Birmingham baseball legend Lorenzo “Piper” Davis. As the capacity crowd of over 10,000 cheered Davis, he must have reflected on his life in the game. He had traveled from rural Alabama to the proving grounds of Birmingham’s industrial leagues, and he had played baseball for 24 years in nearly every corner of the Americas, including the Negro American League, the Eastern, Mexican, Pacific Coast, and Texas Leagues, the Caribbean, and in countless barnstorming games. Piper Davis was a great player, a fine manager, and a scout for many years.

Lorenzo Davis was born on July 3, 1917, in tiny Piper, Alabama, a coal-mining camp about 40 miles south of Birmingham established along with the town of Coleanor by the Little Cahaba Coal Company.1 He was the only child of John and Georgia Davis.2 His father had steady work in the mines, often working long hours to provide for his family.3 Lorenzo was a good student, particularly at math, where he was at the top of his class;4 his father hoped his son could avoid a treacherous life in the mines.5

Lorenzo had an early interest in baseball. He followed the Southern Association’s Birmingham Barons by listening to Bull Connor call their games on the radio.6 He played baseball and basketball in elementary school; as a teenager, he distinguished himself as the best baseball player in his age group, which was known in his community as “the second nine.”7 He batted and threw right-handed, and he played so well that he accepted an invitation to play with the men on “the first nine”; recalling with pride, Piper said, “[s]o they put me over there. I was fourteen then. I’ve played first nine ever since.”8

Because the local school ended in ninth grade, Lorenzo moved to Fairfield, Alabama, in the Birmingham metropolitan area, to live with his mother’s family. There, he attended Fairfield Industrial High School, and met his future wife of nearly 60 years, Laura Perry.9 He earned his lifelong nickname during a basketball game in which the students, not remembering his name but knowing his talent as a basketball player cheered, “We want Piper-Coleanor! We want Piper-Coleanor!”10 Soon he was simply Piper, and he also became a star on the Tigers baseball team, where Willie Mays’s father, Cat, was his teammate.11

Moving to Fairfield introduced Piper Davis to the Negro Leagues, as a number of clubs trained and barnstormed in the South.12After graduating from high school, he “wrote to the Philadelphia Stars for a tryout.”13 Because the Stars wanted him to pay for his own transportation expenses to Mississippi (agreeing to reimburse him only if he made the team), his father persuaded him not to go.14

Instead, Davis enrolled at Alabama State College in Montgomery on a partial basketball scholarship in 1934.15 His father borrowed money from his employer to cover the remainder of his tuition.16 During the second term, a strike at the mine made borrowing more tuition money untenable, and Davis withdrew from college.17 He moved home and worked in the mines with his father until early 1936.18 After an incident at work left a man dead, Davis lost his stomach for mining coal and quit.19 The company payroll clerk would not pay him without an explanation from Davis, who told him, “[J]ust put on there, ‘afraid of mines,’” which the clerk accepted as “a good enough reason.”20 Baseball beckoned once again.

In 1936 Davis signed a contract to play baseball with the Omaha Tigers for $91 a month,21 nearly $1,600 a month in 2017 dollars.22 The Tigers barnstormed from Memphis across the northern half of the Great Plains and into Washington state.23 Considering the Depression Era economy, Davis’s pay was decent for an 18-year-old, but also illusory.24 He found the unending travel by bus, which was necessary to make a living as barnstorming ballplayer, to be “[t]oo much traveling and not enough money”;25 and he was happy he followed his parents’ advice to always hold back enough money to return home.26 Back in Fairfield, he got a job with the Tennessee Coal, Iron and Railroad Company (TCI) making $3-4 a day, and playing on a TCI baseball team.27 When TCI laid him off in 1938, he signed with the Yakima (Washington) Indians.28 The Indians were another barnstorming outfit and Davis spent the next year playing in games against teams from towns across the West; the Indians even toured with the famously long-bearded House of David for a couple of weeks.29 However, he grew disenchanted with his pay, and returned to Fairfield in 1938.

On September 18, 1938, Davis married his high-school sweetheart, Laura Perry, who had waited for him during his baseball travels. He got a job with the American Cast Iron and Pipe Company (ACIPCO) in Birmingham, and played for the Pipemen, the company baseball team, from 1939 until early 1943.30 ACIPCO’s roster included future Black Barons Artie Wilson, Bill Powell, Ed Steele, and Sam Hairston.31 With Davis manning first base, the Pipemen won the Birmingham Industrial League title five years in a row.32 According to the research of Layton Revel, founder of the Center for Negro League Baseball Research, Davis hit an astounding .410 during his playing career with ACIPCO.33

By 1941 the Birmingham Black Barons had taken notice and tried to sign Davis, who weighed 188 pounds with a long 6-foot-3 frame. The following year, at age 24, he played in a few exhibition games with the Black Barons. While playing at Rickwood Field, he first faced Satchel Paige, who toyed with the youngster before striking him out on a fastball that he had difficulty even seeing.34 Manager Winfield Welch finally persuaded Davis to leave ACIPCO permanently and sign with the Black Barons for the 1943 season. They offered him $300 per month plus $2 a day for meals. When Abe Saperstein, who acted as the Black Barons’ business manager for owner Tom Hayes, found out that Davis could play basketball, he increased the monthly offer by $50 and Piper Davis became a two-sport star with the Black Barons and the Harlem Globetrotters.35

Davis played basketball with the Globetrotters for three straight winters, from 1943-44 to 1945-46, and later played with them briefly in the early 1950s.36 Playing two professional sports year-round, along with the uncomfortably long bus rides, took a toll on his body.37 During the summers the Black Barons rarely had a day off; while they often appeared at Rickwood on Sundays, the rest of their games were played on the road – from rural communities in Alabama and Mississippi to Northern cities like New York, Chicago, and Philadelphia – and always by bus.38

Davis once recalled, “I made both teams and for three years played both seasons with a week off in between to see my family. I quit when I found my legs shaking after a Globetrotters game at the end of the 1946 season.”39 From 1947 to 1956, he made a living during the winters by playing baseball in Puerto Rico (with the Mayaguez Indios, the Caguas Criollos, and the Ponce Leones), Venezuela, and the Dominican Republic. Winter baseball allowed him to bring his family along during the holidays.40 In 1949, while he was the player-manager of the Ponce Leones, a fire broke out at a plant adjacent to the house the Davis family was renting, but he arrived in time to kick the door in and get everyone to safety.41

Davis also barnstormed during most offseasons, both with the Black Barons and with various bands of all-stars. In 1944 The Sporting News reported that the Black Barons defeated Augie Galan’s major-league all-stars, 7-4.42 The Black Barons won the California Winter League Championship that season.43 Davis also barnstormed with Satchel Paige’s All-Stars and faced Bob Feller’s all-star squad.44 In one game, Davis hit a home run off Eddie Lopat.45 Although he had great respect for Bob Feller and his famed fastball, he believed Satchel threw harder: “Satchel was the best pitcher I ever faced, and the best I’ve seen.”46 He also credited Satchel as “[t]he only hero I looked up to. …”47

Piper Davis was the Black Barons’ most versatile player. He regularly played first base, second base, shortstop, and outfield from 1943 to 1949 before crowds at Rickwood Field that were often larger than those that attended the games of the Double-A Southern Association’s Barons.48 So great was his ability to adapt defensively that double-play partner Artie Wilson asserted, “[H]e was a superstar-type player like Pete Rose [and] could play any position and play it like he had been playing it all the time.49 At the plate Davis shone as a hitting machine for the Black Barons. From 1945 to 1948, he terrorized opponents’ pitching staffs while consistently posting batting averages well over .300.50 The right-hander was a line-drive hitter with good power.51 By 1945, Dodgers general manager Branch Rickey was aware of Davis’s strong performance, and considered offering him a contract;52 he finally decided Davis was too old and instead signed Jackie Robinson, who was only 18 months younger.53

During Davis’s tenure with Birmingham, the Black Barons would have rivaled the Kansas City Monarchs as the most dominant club of the era had it not been for the Homestead Grays. The Negro National League champion Grays defeated the Black Barons in the Negro World Series in 1943, 1944, and 1948. In the ’43 World Series, Birmingham came closest to a title, narrowly losing to the Grays, four games to three. Davis lamented, “[W]e were short handed, but we carried them to the limit. We never did win a World Series.”54

In 1945 Davis won election to the West squad for the East-West All-Star Game, but he missed the game after being suspended for shoving an umpire during an argument over a call.55 From 1946 to 1949, Davis played in seven East-West All-Star Games as a second baseman and compiled a solid .308 batting average for the West in black baseball’s premier biannual event.56 He paced the West with two hits and a run batted in, and he also scored a run in the 1946 contest at Griffith Stadium.57 The following year, at Comiskey Park, he had two more hits, including a double, walked, scored a run, and stole a base in the West’s 5-2 win.58 James Riley called him “a master of the double play”;59 the box scores from those seven All-Star Games agree, telling the story of Davis’s stalwart defense: he participated in 11 double plays while committing no errors.60

In 1947 the Pittsburgh Pirates and Philadelphia Phillies were reportedly scouting Davis and his teammate Artie Wilson.61 Later that summer, the St. Louis Browns purchased a 30-day option on Davis and requested that the Black Barons play him exclusively at first base.62 The option expired in August, and Davis remained with the Black Barons. The initial explanation was that Black Barons owner Tom Hayes turned down the offer because the Browns wanted to send Davis to the Class-A Elmira Pioneers in New York, while Hayes believed he should go straight to St. Louis.63 The Browns were the worst team in baseball and had nothing to lose by bringing Davis directly to the big leagues. They had already signed and released two black players from the Monarchs, Hank Thompson and Willard Brown, who had “struggled to adjust to the pitching and were treated poorly by their white teammates” in St. Louis.64 That failed experiment surely affected general manager Bill DeWitt’s decision to assign Davis to the minors. Later reports surfaced that the Browns also tried to have Davis take a pay cut of nearly 30 percent ($150 per month), which he refused.65 DeWitt must have known that such an offer was unrealistic, if not insulting.

By 1948, the Black Barons named Davis, now 30, as player-manager. After batting .353 for the season,66 he skippered Birmingham to a thrilling Negro American League Championship Series victory over Buck O’Neil’s Monarchs before falling to the Grays in the last Negro Leagues World Series.67 In the second game of the championship series against the Monarchs, Davis hit a ball over Rickwood’s enormous scoreboard, which was “one of the longest balls in Rickwood history.”68 Davis had blended young stars Jimmy Zapp, Bill Greason, and Wiley Griggs with veterans Artie Wilson, Bill Powell, Jimmie Newberry, Jehosie Heard, Lloyd Bassett, Joe Scott, and Ed Steele to capture the NAL pennant. However, it was his discovery and signing of 17-year-old Willie Mays, who was playing for the Chattanooga Choo Choos in the Negro Southern League, which gave the Black Barons their youngest star.69 Davis told the tale to Chris Fullerton, author of Every Other Sunday:

The story behind Willie Mays is that when I was in high school at Fairfield, I played with Willie Mays’s daddy [Cat], before Willie was born. I had heard about Willie Mays. … We were in Chattanooga, and hotel reservations was rough for negroes, only one or two hotels, usually two. After our game in Chattanooga, Willie and them came into Chattanooga looking for rooms and that was the first time I’d seen him. I talked with him, didn’t say nothing about joining us because I hadn’t seen him play. I told him, “if you’re out playing ball for money, you can’t play no kind of competition in high school next year.” [Willie said], “I don’t care. The next week we played in Atlanta, same thing. I said, “I see you’re still out here.” [Willie said], “Yeah, but I’m not going to play no more, the man messed with our money.” I said, “Okay, if you want to play, and your daddy lets you play, have him call me Sunday morning at ten o’clock.” His daddy called me and said, “if he wants to play, let him play.” I said, “Okay, have him out at the ball park at twelve o’clock.” Now, I needed an outfielder … I started him off in the outfield just to see if he had a good arm … so I put him in center field, and he handled that pretty good. That was my first year managing.70

Over the next two seasons, Davis took Mays under his wing and taught the phenom all he knew about the game.71 He also carefully protected him from trouble off the field.72 From the dugout he counseled Mays on how to spot a pitcher’s tendencies and how to hit breaking balls, and he reminded him to always be patient at the plate.73 Once, after Cleveland Buckeyes pitcher Chet Brewer struck him in the ribs with a fastball, Mays fell hard to the ground in pain.74 Davis calmly walked to home plate and talked with Mays. He asked him if he could see first base. After Mays told him that he could, Davis instructed him to “get on up and get down there. When you get to first, steal second. When you get to second steal third. When you get to third, steal home.”75 After Davis’s lessons, Willie Mays later found playing in the major leagues to be an easy task.76 During his 1979 Hall of Fame induction speech, Mays credited both Piper Davis and Artie Wilson as being “very good teachers” to him.77

One of Davis’s fondest memories during the 1948 season came against future major-league pitcher Joe Black, who was pitching for the Baltimore Elite Giants. In the first game of a series in Baltimore, the Black Barons trailed but loaded the bases in the ninth. With two outs, and needing only a hit to take the lead, Davis came to bat. He felt more than normal pressure because scouts from the Boston Red Sox were watching, and Black struck him out to end the game. Davis got his revenge on Black the following night in front of the same scouts. He told Prentice Mills, “I wasn’t going to let Black do it to me again. … He threw me a fastball, and I hit it pretty hard. I knew I had a base hit, but as I was coming around between first and second I saw the umpire signal a home run! I think that was the most memorable home run I ever hit.”78

Bill Greason, a starting pitcher, was in his first season with the Black Barons in 1948. He won the pennant-clinching game against the Monarchs as well as the only game the Black Barons won in the World Series. Greason praised Davis as the greatest manager he played for and one of the finest men he knew. Davis insisted that the players dress well, avoid profanity, and carry themselves with dignity; he also demanded their maximum effort on the field. According to Greason, Davis “wanted us to be professionals on the field, and be gentlemen off the field; and we had one of the finest teams you would ever want to play with because of his kind of character.”79

The statistical record of Davis’s career with the Black Barons is not fully known due to sporadic record-keeping. Baseball-Reference.com credits Davis as an accomplished .293 hitter during his eight seasons in the Negro American League. However, Dr. Layton Revel, Executive Director for the Center for Negro League Baseball Research, determined that Davis had a .348 average during his career with the Black Barons. 80 Revel’s conclusions are based on the Howe News Bureau’s official statistics of the Negro American League, which were compiled at the time of each season.81

In July 1949 Davis was hitting .392 for the Black Barons and remained a “good big-league prospect” amid reports that the Cincinnati Reds were scouting him.82 The Boston Red Sox passed on signing Willie Mays and inked Davis to a contract in 1950.83 The Louisville Colonels and the Birmingham Barons were the Red Sox’ top minor-league affiliates. The fact that the Barons were in the same city and even played in the same ballpark as Davis’s Black Barons was a cruel footnote to his signing with the Red Sox organization since the Birmingham Barons could not be integrated due to Jim Crow laws.84 Accordingly, Red Sox GM Joe Cronin assigned him to a Northern affiliate, the Class-A Scranton (Pennsylvania) Miners.85 The Red Sox paid Davis $7,500 to sign, and agreed to pay him another $7,500 if he was still on the club after May 1.86 Signing Davis might have been an odd decision because of the presence of slugger Walt Dropo,87 Boston’s first baseman, who won the American League Rookie of the Year award in 1950. Of course, Davis could have played any position.

The insensitive treatment Davis endured in Scranton extended from the locker room to the diamond. During one game with the Miners, a heckler yelled a racist insult as he stood at the plate. Davis responded with a home run. He walked over to the stands and said, “Take that!” as other fans cheered him.88 Davis played just 15 games in Scranton. Although he was leading the Miners in batting average, runs batted in, and home runs, the Red Sox released him and avoided making the second payment, citing “economic conditions” as their excuse.89 Years later, Davis told Chris Fullerton, “when Boston released me, that took all the joy out of it for me.”90

After his release, Davis returned to Birmingham and batted .383 for the Black Barons.91 Later in the ’50 season he signed with Jalisco in the Mexican League.92 There, he played with former Black Barons teammate Bill Greason for the first-place Charros.93

In 1951 another old teammate, Artie Wilson, who was playing with the Oakland Oaks in the Pacific Coast League, called Davis and told him that the Oaks wanted to sign him.94 Though he was 33 years old when he first signed with Oakland, Davis played seven seasons in the PCL with the unaffiliated Oaks and later the Los Angeles Angels. Despite his advancing years, he posted a solid .288 batting average during his career in the PCL.

On June 12, 1951, Davis had one of his finest performances as a professional with four hits in four at-bats, including two home runs and a double, while driving in five runs to lead the Oaks to a win over San Diego.95 Davis did not avoid controversy in the PCL, however. Late in July1952, during a game against San Francisco, Seals pitcher Bill Boemler slapped Davis with a hard tag at home plate.96 He took offense and punched Boemler twice, knocking him down. According to The Sporting News, “both clubs joined in a five-minute melee at home plate [but] none of the players was tossed out of the game after order was restored [because] … there would have been no one left to play.”97 White players on the Oaks had defended their black teammate in the fight, signaling that a real change was taking place in baseball; the Oaks players not only accepted Davis, they fought for him.98 On the final day of the 1952 season, Oaks manager Mel Ott started Davis as his pitcher, and then played him for one inning at every position, as Oakland honored its talented star.99 It was Ott’s last day as a manager and he praised Davis, saying, “Piper Davis is the best all-around player I ever saw.”100 Davis batted .306 in ’52, and hit .287 during his five seasons in Oakland.

After he turned 37, the Oaks traded Davis to the Los Angeles Angels, an affiliate of the Chicago Cubs. Despite batting .253 in 1955, he bounced back in the 1956 season to hit .316 as a part-time utility player for the first-place Angels. Art Clarkson, who later owned the Birmingham Barons, was a teenager living in Los Angeles that season. Clarkson was a fan of the Hollywood Stars who regularly attended their games; he disliked the Angels but remembered Davis as a star for the Los Angeles team.101

The Cubs sent Davis down to the Double-A Fort Worth Cats in 1957. According to the Cubs, “The idea was for Piper to help coach and instruct some of the younger players on the Cats while playing a utility role on the roster.”102 In his final season in professional baseball in 1958, Davis batted .282 for the first-place Cats as a 40-year-old.

Davis retired as a player and moved back to Birmingham. Initially, he worked for the Harlem Globetrotters again, “doing everything from coaching to driving the team bus during the 1958 and ’59 seasons, and accompanied the team on a tour around the world in 1959.”103 He also returned to Rickwood Field as the manager of the Birmingham Black Barons for the 1959 season.104 Under his leadership, the team returned to a familiar position as it won the Negro American League Championship.105 After that season, he never managed in professional baseball again. Davis explained, “The old Negro American League was about gone, really just an exhibition outfit by then, but I was glad to go back with the team one last time.”106 With Organized Baseball now integrated, the shrinking talent pool caused the Negro Leagues to wither and die within a few years.107

Davis worked for many years as the night auditor for Birmingham’s A.G. Gaston Motel. The math skills he had evidenced early in life continued to serve him well, and he impressed the hotel’s owner with his ability to keep the books.108 For a time he also managed the Honey Bowl in Birmingham, a state-of-the-art bowling facility.109 At Birmingham’s Sardis Baptist Church, he served as a deacon, an usher, and a member of the choir.110

Piper Davis never strayed far from baseball, though. In 1960 he signed as a scout with the Detroit Tigers.111 He was a player-coach for Stockham Valves from 1962 to 1964 and managed the industrial squad from 1965 to 1967.112 He scouted for the major leagues’ Central Scouting Bureau from 1968 to 1970.113 In 1971 the St. Louis Cardinals hired him as a scout and he worked for the club until 1976.114 He last scouted for the Montreal Expos from 1984 to ’85.115

In 1981 Davis appeared at the Negro League reunion in Ashland, Kentucky. Always a teacher of the game, he happily demonstrated the fine nuances involved in a properly-turned double play.116 Even at 64, while wearing an old glove, “he handled each throw so quickly that it appeared he was spearing the ball with his throwing hand.”117

In 1985 Barons owner Art Clarkson organized an Old-Timers Game to celebrate the 75th anniversary of Rickwood Field.118 Piper Davis managed one team and Ben Chapman (the former Phillies manager who had verbally assaulted Jackie Robinson in 1947) managed the other.119 To his surprise, historian Allen Barra saw the two men “laughing and slapping each other on the back.”120

Davis retired for good in 1986.121 He was inducted into the Alabama Sports Hall of Fame in 1993,122 and the Birmingham Barons recognized him as a special guest at the inaugural Rickwood Classic in 1996. The latter honor filled him with pride, although his daughter Faye insisted, “You would have never known it.”123 Kevin Scarbinsky documented the moment for the Birmingham News:

During the pregame ceremonies, Davis stood near one end of the line of former players, Dropo near the other. When they introduced Davis, he stepped forward and tipped his cap. When they introduced Dropo, Davis stepped back, walked the length of the line and shook his hand. That’s the way it should have been in 1948. Two players. One park. One team. Sometimes if you turn back the clock, you can help make up for lost time.124

After the game started, Piper and Faye began to leave Rickwood because the June weather had turned hot.125 As they exited, she was struck by a foul ball on the leg, and the same ball still sits on her desk today.126

On May 21, 1997, Piper Davis died of a heart attack. At his funeral, Bill Greason, Jimmy Zapp, Lyman Bostock, Bill Powell, Joe Black, Sam Hairston, Rufus Beal, and Charlie Speights served as honorary pallbearers.127 His wife, Laura, died on November 25, 2012. They are buried side-by-side in Birmingham’s Elmwood Cemetery.

The community that gave Piper Davis his nickname is a mere memory, having been replaced by a marker that does not mention its most famous son. But Davis’s legacy in baseball is preserved by his inclusion in the Alabama Sports Hall of Fame and the Birmingham Barons Hall of Fame.128 Additionally, two books have been dedicated to him,129 and an international youth baseball league bears his name.130 Photographs of Piper Davis are displayed proudly throughout Rickwood Field, and the Rickwood Classic has been played annually for more than 20 years.

In reflecting upon the entirety of his baseball career, Davis modestly remarked, “I had some beautiful moments.”131 Barra put Davis’s career in perspective when he noted that “most of the players and managers I talked to over the years thought Piper could have been a Hall of Famer himself.”132

This biography appears in “Bittersweet Goodbye: The Black Barons, the Grays, and the 1948 Negro League World Series” (SABR, 2017), edited by Frederick C. Bush and Bill Nowlin.

Acknowledgements

The author deeply appreciates Faye Davis and Rev. Bill Greason for allowing him to interview them for this chapter. In addition, David Brewer, the Operations Director of the Friends of Rickwood, and Dr. Layton Revel, the founder of the Center for Negro League Baseball Research, were both very helpful in providing the author with important research materials and suggestions.

Notes

1 Theodore Rosengarten, “Reading the Hops: Recollections of Lorenzo Piper Davis and the Negro Baseball League,” Southern Exposure, May 1977: 64.

2 John Klima, Willie’s Boys (Hoboken, New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 2009), 8; “A Service of Worship Celebrating the Life of Deacon Lorenzo Davis ‘Piper,’ Saturday, May 24, 1997, Sardis Baptist Church, Birmingham.

3 Klima, 64.

4 Faye Davis, telephone interview with author, December 9, 2016; Piper Davis, interview with Chris Fullerton, Birmingham Public Library Digital Collection, March 8, 1993.

5 Rosengarten, 66.

6 Rosengarten, 65.

7 Rosengarten, 64.

8 Ibid.

9 Rosengarten, 66; Klima, 11.

10 Klima, 11; Rosengarten, 66; Faye Davis, telephone interview.

11 Klima, 12.

12 Rosengarten, 65-66.

13 Rosengarten, 66.

14 Ibid.

15 Ibid.

16 Rosengarten, 66; and Prentice Mills, “The Baron of Birmingham, An Interview with Lorenzo ‘Piper’ Davis,” Black Ball News, Vol 1. No. 5, 1993: 4.

17 Ibid.; Rosengarten, 66; and Klima, 12.

18 Mills, 4; Rosengarten, 66; and Klima, 12.

19 Rosengarten, 67.

20 Ibid.

21 Ibid.

22 bls.gov/data/inflation_calculator.htm.

23 Rosengarten, 67-68.

24 Rosengarten, 68.

25 Ibid.

26 Mills, 5; Fullerton interview.

27 Rosengarten, 68; Dr. Layton Revel and Luis Munoz, Forgotten Heroes: Lorenzo ‘Piper’ Davis (Carrollton, Texas: Center for Negro Baseball Research, 2010), 1; Fullerton Interview.

28 Rosengarten, 68; Revel & Munoz, 1.

29 Rosengarten, 68; Mills, 5.

30 Rosengarten, 69; Revel & Munoz, 5.

31 Fullerton interview; Sam Hairston, interview with Ben Cook, Birmingham Public Library Digital Collection, June 16, 1995; Willie Powell, interview with Ben Cook, Birmingham Public Library Digital Collection, 1995; Mills, 7.

32 Revel & Munoz, 5.

33 Ibid.

34 Rosengarten, 74-75.

35 Rosengarten, 71.

36 Revel & Munoz, 28.

37 Ibid.; Shelley Smith, “Remembering Their Game,” Sports Illustrated, June 6, 1992: 92.

38 Fullerton interview; Rosengarten, 71.

39 Smith.

40 Faye Davis, telephone interview with author.

41 Ibid.

42 “Major League Flashes,” The Sporting News, October 26, 1944.

43 Revel & Munoz, 9-10.

44 Rosengarten, 75.

45 “Feller’s Stars Cut Win Path to Coast,” The Sporting News, October 22, 1947: 6.

46 Rosengarten, 75.

47 Fullerton interview.

48 Ibid.; Rosengarten, 71.

49 Bill Plott, “Piper Davis Was a Baseball Legend in Birmingham,” Birmingham News, May 22, 1997: 8D.

50 Revel & Munoz, 14; James A. Riley, The Biographical Encyclopedia of The Negro Baseball Leagues (New York: Carroll & Graf Publishers, 2002), 218.

51 Rosengarten, 77.

52 Phil Dixon, The Negro Baseball Leagues, A Photographic History (Mattituck, New York: Amereon House, 1992), 270; Larry Powell, Black Barons of Birmingham (Jefferson. North Carolina: McFarland & Company, Inc., 2009), 170.

53 Chris Fullerton, Every Other Sunday (Birmingham, Alabama: R. Boozer Press, 1999), 92; Powell, 170; James S. Hirsch, Willie Mays, The Life, the Legend (New York: Scribner, 2010), 38.

54 Rosengarten, 71.

55 Mills, 8.

56 Larry Lester, Black Baseball’s National Showcase, The East-West All-Star Game, 1933-1953 (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2001), 418.

57 Lester, 273.

58 Lester, 291-93.

59 James A. Riley, Of Monarchs and Black Barons (Jefferson. North Carolina: McFarland & Company, Inc., 2012), 194.

60 Lester, 274, 279, 295, 302, 313, 322, 336.

61 “Report Pirates, Phillies See Colored Stars,” Richmond Afro-American, July 5, 1947.

62 Frederick Lieb, “Gates Rusting, Browns Rush in 2 Negro Players,” The Sporting News, July 23, 1947, 20.

63 Revel & Munoz, 15 (citing the Pittsburgh Courier); “Offer to Davis Nixed as Browns’ Option Ends,” Richmond Afro-American, August 9, 1947.

64 Klima, 42.

65 “Series Sidebars,” Richmond Afro-American, October 11, 1947.

66 Riley, Of Monarchs and Black Barons, 195.

67 Jeb Stewart, “Remembering the 1948 Birmingham Black Barons,” Rickwood Times, Vol. 18, May 29, 2013: 2.

68 Tim Cary, “Slidin’ and Ridin’, At Home and on the Road With the 1948 Birmingham Black Barons,” Alabama Heritage, Fall 1986: 31.

69 William Plott, The Negro Southern League (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, Inc., 2015), 178.

70 Chris Fullerton, Every Other Sunday.

71 Riley, Of Monarchs and Black Barons, 195-198.

72 Klima, 108-111.

73 achievement.org/achiever/willie-mays/#interview; Ben Cook, Good Wood (Birmingham, Alabama: R. Boozer Press, 2005), 68, Hirsch, 45.

74 Klima, 116-17.

75 Klima, 117; Hirsch, 46.

76 John Holway, “‘They Made Me Survive,’ Mays Says at a Reunion of Negro League Stars,” The Sporting News, July 18, 1981.

77 Willie Mays’s 1979 Hall of Fame Induction Speech, 21.

78 Willie Mays’s 1979 Hall of Fame Induction Speech, 9-10.

79 Rev. Bill Greason, telephone interview with author, December 21, 2016.

80 Revel & Munoz, 14.

81Dr. Layton Revel, telephone interview with author, February 14, 2017.

82 “The Future of Negroes in Big League Baseball,” Ebony, May 1, 1949: 36; Oscar Ruhl, “From the Ruhl Book,” The Sporting News, March 30, 1949: 15.

83 David Nevard and David Marrasco, “Who Was Piper Davis?” Buffalo Head Society (2001), 9. Reprinted in Bill Nowlin, ed., Pumpsie and Progress: The Red Sox, Race and Redemption (Burlington, Massachusetts: Rounder Books, 2010).

84 Nevard & Marrasco, 10.

85 Mills, 11.

86 Ibid.

87 Riley, 198-199.

88 Ibid.

89 Fullerton interview.

90 Ibid.

91 Russ Cowans, “‘Go All the Way’; Rule of Hurlers With Monarchs,” The Sporting News, May 31, 1950, 20; Revel & Munoz 14.

92 Revel & Munoz, 17.

93 Rev. Bill Greason, telephone interview with author; baseball-reference.com/register/league.cgi?id=e56ca649.

94 Mills, 11; Nevard and Marrasco, 11; Revel & Munoz, 17.

95 “Pacific Coast League,” The Sporting News, June 27, 1951: 27-28.

96 John Old, “Loop Quakes With Fight and Protests,” The Sporting News, August 6, 1952: 23.

97 Ibid.

98 Mills, 11-12.

99 Sam Schnitzer, “Boyd Clinched Bat Title on Final Day,” The Sporting News, Oct. 1, 1949: 40-42.

100 Dave Kindred, “From Miner to Majors,” The Sporting News, June 30, 1997: 6.

101 Art Clarkson, telephone interview with author, December 20, 2016.

102 Revel & Munoz, 19.

103 Mills, 12.

104 Ibid.

105 Marcel Hopson, “Black Barons, Memphis Divide, End Official NAL Season,” Birmingham World, August 29, 1959.

106 Mills, 12.

107 Rosengarten, 78.

108 Faye Davis, telephone interview.

109 Ibid.; “Big Boom in Bowling,” Ebony, September 1, 1962: 36.

110 “A Service of Worship Celebrating the Life of Deacon Lorenzo Davis ‘Piper.’”

111 Watson Spoelstra, “Dykes Junks Rest Cure, Plants Fading Rocky Kaline in Garden, The Sporting News, June 29, 1969.

112 Faye Davis, telephone interview; Revel & Munoz, 29.

113 Revel & Munoz, 29.

114 Neal Russo, “Cards Told Shannon Is Out for Season,” The Sporting News, February 27, 1971; Revel & Munoz, 29.

115 Revel & Munoz, 29.

116 Bruce Anderson, “Time Worth Remembering,” Sports Illustrated, July 6, 1981: 46.

117 Ibid.

118 Art Clarkson, telephone interview.

119 Ibid.

120 Allan Barra, “Reconsidering the ‘Alabama Flash,’” Weld for Birmingham, April 26, 2016: 4; Allan Barra, “What Really Happened to Ben Chapman, the Racist Baseball Player in 42?,” The Atlantic, April 15, 2013: 5.

121 Faye Davis, telephone interview.

122 ashof.org/index.php?src=directory&view=company&srctype=detail&refno=244&category=Baseball.

123 Faye Davis, telephone interview.

124 Kevin Scarbinsky, “Rickwood Makes Up for Lost Time,” Birmingham News, June 13, 1996: 1-D.

125 Faye Davis, telephone interview.

126 Ibid.

127 “A Service of Worship Celebrating the Life of Deacon Lorenzo Davis ‘Piper.’”

128 milb.com/content/page.jsp?ymd=20080505&content_id=41116562&sid=t247&vkey=team4.

129 Allan Barra, Rickwood Field (New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 2010); Klima.

130 piperdavisbaseball.org/our-history.

131 Fullerton interview.

132 Allan Barra, “What Really Happened to Ben Chapman, the Racist Baseball Player in 42?”

Full Name

Lorenzo Davis

Born

July 3, 1917 at Piper, AL (US)

Died

May 21, 1997 at Birmingham, AL (US)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.