George Bamberger

Baltimore left-hander Mike Cuellar pitched a shaky first inning in Game Five of the 1970 World Series. The Cincinnati Reds touched him for three runs on four hits — a single and three doubles. The Orioles bullpen was active as the inning ended. Cuellar came into the dugout, grabbed a towel, wiped his face. His catcher, Andy Etchebarren, took that simple act as a promising sign. “By that time,” he said, “he was warmed up.”1

Baltimore left-hander Mike Cuellar pitched a shaky first inning in Game Five of the 1970 World Series. The Cincinnati Reds touched him for three runs on four hits — a single and three doubles. The Orioles bullpen was active as the inning ended. Cuellar came into the dugout, grabbed a towel, wiped his face. His catcher, Andy Etchebarren, took that simple act as a promising sign. “By that time,” he said, “he was warmed up.”1

Despite winning 24 games in the regular season, the Cuban-born pitcher had lasted only 4⅓ innings in the opening game of the American League Championship Series. He was knocked off the mound after just 2⅓ innings of the second game of the World Series. Another short outing seemed in the works.

The battery huddled in the runway behind the home dugout at Memorial Stadium, where they were joined by pitching coach George Bamberger. Two of the hits, by Johnny Bench and Hal McRae, had come off screwballs high in the strike zone. A decision was made — no more scroogies, a lot more curves.

Cuellar retired the next 10 Reds, issued a walk, then stymied six more batters in a row. He gave up a pair of singles in the seventh, but got out of the inning to complete the game, sewing up the World Series in dominating fashion.

Bamberger, a quiet man with some unorthodox ideas about handling hurlers, flourished as pitching coach of the Orioles from 1968 to 1977. A 20-win season is a standard of excellence for a starting pitcher. Bamberger had 18 pitchers reach that mark, four of them — Cuellar, Jim Palmer, Pat Dobson, and Dave McNally — doing so in 1971, the third consecutive year in which the O’s won the pennant.

“He’s one of the game’s greatest teachers,” longtime Orioles manager Earl Weaver once said. “ ‘Throw strikes,’ he would say. There is nothing complicated about baseball. Maybe that’s what makes George so good — there’s nothing complicated about George.”2 Shortly before Bamberger’s death in 2004, Weaver said, “If there was a Hall of Fame for pitching coaches, he should be there without a doubt.”3 Frank Cashen, the Orioles President during Bamberger’s years in Baltimore, said, simply, “He was the best pitching coach I ever saw.”4

Where Weaver was flamboyant and volatile, Bamberger was calm, unflappable, a pitcher’s friend. He was also nearly deaf in his right ear, so he made a point of sitting on Weaver’s left in the dugout.

Bamberger’s own major-league career was brief and undistinguished. In 18 seasons in the minors, he transformed himself from a wild thrower into a control pitcher who set a mark for consecutive innings pitched without issuing a walk. After his time coaching for the Orioles, he had two stints managing the Milwaukee Brewers, who were known as Bambi’s Bombers, with an unsuccessful spell as skipper of the New York Mets sandwiched in between the Milwaukee stints.

George Irvin Bamberger was born on Aug. 1, 1923, in Staten Island, New York. He attended McKee High before entering the US Army in 1943. The 5-foot-11½, 180-pound right-hander signed with the New York Giants as an amateur free agent in 1946, about the time two years were shaved from his age. The official guides always listed his birth year as 1925. He debuted in 1946 with the Class C Erie (Pennsylvania) Sailors of the Middle Atlantic League, going 13-3 with a league-leading earned-run average of 1.35. He was then promoted to the Class B Manchester (New Hampshire) Giants and, in 1948, to the Triple-A Jersey City Giants. He led the International League in wild pitches in 1949 with 11, though he also tied for the league lead in shutouts with five. Pitching for the Oakland Oaks the following season, he led the Pacific Coast League in wild pitches with 13.

During the 1950 season Bamberger married Wilma Morrison of New Jersey at First Presbyterian Church in Oakland. The best man was Oaks second baseman Bobby Hofman. The entire ballclub, including president Brick Laws and manager Charlie Dressen, joined the couple afterwards for a cocktail hour followed by a buffet dinner.

Bamberger made his major-league debut with the Giants on April 19, 1951, during the second game of a doubleheader at Boston against the Braves. In two innings, he gave up two runs on a walk and three hits, including a home run by Sam Jethroe. In his only other appearance with the Giants that season, he failed to register an out while surrendering two more runs.

Bamberger was soon demoted to play for the Ottawa Giants in the International League. On Father’s Day he pitched a no-hitter in a 1-0 victory over the Maple Leafs at Toronto. Not only did Bamberger hold Toronto hitless, but he was responsible for the game’s only run, coaxing a bases-loaded walk on four pitches from mound rival Russ Bauers in the second inning. After the game Bamberger lit a fat cigar, in celebration not of his no-hitter but of the birth of daughter Judy in New York the night before.

In 1952 Bamberger started the season with the Giants again, appearing in five games and allowing four runs in four innings. In June he was traded back to the Triple-A Oakland Oaks in exchange for pitcher Hal Gregg.

He spent four seasons as a starting pitcher for the Oaks, compiling a 52-44 record. The Oaks moved to Vancouver (and joined the Baltimore system) for the 1956 Pacific Coast League season, and Bamberger went along, spending seven seasons with the Mounties. He went 9-14 his first season in British Columbia, complaining of a sore arm that cost him his fastball. In 1957 new manager Charlie Metro convinced him the only way to recover was to “throw, throw and throw.”5 It worked. Bamby’s exploits at Capilano (now Nat Bailey) Stadium made him a perennial fan favorite. Bamberger carried himself like someone who knew he belonged in The Show and had been left behind by an oversight that would surely soon be corrected.

“Bamberger was a chesty guy with thinning hair,” Denny Boyd of the Vancouver Sun once wrote, “a nose the size of a wedge of pie and a dimple in which you could catch thrown balls.” Boyd dubbed him the Staten Island Stopper. The pitcher’s limited repertoire — a so-so fastball, a deceptive changeup, a wicked curve that dipped like the new roller-coaster at the city’s exhibition grounds — was enhanced by the occasional use of a spitball, an illegal pitch and a scofflaw’s best hope. “We all knew he used it,” Boyd wrote, “but we could never get him to admit to throwing the wet one.”6 Bamby acknowledged that he had a special pitch that he called the Staten Island Sinker. It certainly was wet like a sink.

In 1958 Bamberger established a league record by pitching 68⅔ consecutive innings — the equivalent of more than seven complete games — without allowing a base on balls. The old mark of 64 innings had been set by Julio Bonetti in 1939. Bamberger’s record stood for more than four decades. The streak began on July 10, after he walked a batter in San Diego in the fourth inning. He recorded his 100th PCL victory in his next start, for which the Mounties held a George Bamberger Day on August 1. The club gave him 100 Canadian silver dollars. In return, Bamby beat Seattle 6-3, again without walking any batters.

“When you come right down to it, there is no excuse for walking a batter,” Bamberger told Boyd in 1958. “It’s accepted as normal, but it isn’t normal; it’s a mistake. If you throw four bad pitches, you have made four mistakes. There is no other sport where you can survive making that many mistakes.”7

The streak ended on Aug. 14, when a Phoenix pinch-hitter walked on four pitches. The record remained unchallenged until bettered by Nashville’s Brian Meadows in 2003.

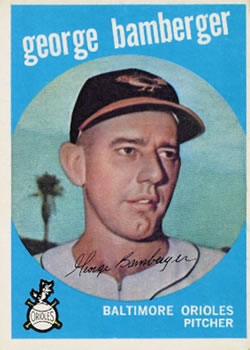

Bamberger’s final cup of coffee in the bigs came courtesy of the Orioles, who used him three times in April 1959. His entire major-league career involved pitching just 14⅓ innings for two teams over three seasons separated by eight years. He had no wins or losses and one save in relief, and carries into eternity an inflated ERA of 9.42. He returned to Vancouver and kept pitching.

In a 1962 game in Vancouver, Bamberger took part in a wacky episode. He was outfitted with a radio receiver sewn into an inside pocket of his uniform. It looked as though he had a cardboard pack of cigarettes in his undershirt. Unseen in the Vancouver dugout, manager Jack McKeon barked commands into a transmitter. The skulduggery failed to catch out any opposing baserunners, although it did bamboozle fans and the first baseman, who took one unexpected pickoff throw in the chest. Before long, baseball banned the use of radios on the field.

Bamberger added coaching duties to his responsibilities in 1960 while still pitching for the Mounties. After retiring as a player at the end of the 1963 season, which he spent at Dallas-Fort Worth, Bamberger worked for the Orioles as a minor-league pitching instructor. He was hired as the parent club’s pitching coach in 1968, replacing Harry Brecheen, who had held the post for 14 seasons. Manager Hank Bauer announced in spring training that he was tired of having pitchers with sore arms on his roster. Bauer would not last the season, but the Orioles found a solution to the problem in their new pitching coach.

Bamberger’s theory was that sore arms and elbows resulted from underwork, not overwork. He insisted that his pitchers run every day, even if tired, even on the road, so he ordered 35 minutes of sprints from foul pole to foul pole. “When you pitch, and your legs get tired from lifting them up on every windup, you can lose coordination,” he said. A shift in the mechanics could lead to loss of control, which could lead to wildness and sore arms.8

He also had his pitchers play catch for 15 minutes between starts, with 20 minutes of hard throwing the prescription two days after every start. He believed in pitchers throwing many innings and completing as many starts as they could. In 1970, Palmer threw 305 innings, Cuellar 297⅔, and McNally 296.

“My whole idea is to throw the ball over the plate,” Bamberger told Dave Anderson of the New York Times in 1979. “The most important pitch is a strike. But the trick is to change speeds. Trying to pinpoint a pitch is crazy. Throw the ball down the middle, but don’t throw the same pitch twice. Change the speed.”9

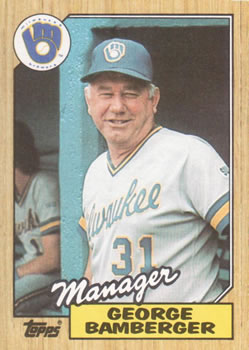

Though regarded by many as solely a pitching specialist, in 1978 Bamberger was hired to manage the Milwaukee Brewers, who had yet to post a winning season in their eight year history. Remarkably, he turned the perennial also-ran into contenders as Bambi’s Bombers posted 93 wins in 1978 and 95 in 1979. An amiable, happy man, the manager was known to join fans in the parking lot of County Stadium for postgame tailgate parties. After suffering a heart attack during spring training in 1980, he underwent a quintuple bypass. He returned in June, but did not last the season.

Though regarded by many as solely a pitching specialist, in 1978 Bamberger was hired to manage the Milwaukee Brewers, who had yet to post a winning season in their eight year history. Remarkably, he turned the perennial also-ran into contenders as Bambi’s Bombers posted 93 wins in 1978 and 95 in 1979. An amiable, happy man, the manager was known to join fans in the parking lot of County Stadium for postgame tailgate parties. After suffering a heart attack during spring training in 1980, he underwent a quintuple bypass. He returned in June, but did not last the season.

Two years later, in 1982, Bamberger became the skipper of the New York Mets. The 58-year-old florid and balding manager was greeted by a memorable description in New York magazine. “Bamberger resembles George Kennedy,” wrote Vic Ziegel, “but the voice is Art Carney’s Ed Norton.”10 The Mets were woeful, and could finish only 65-97 during Bamberger’s one complete season. “I don’t want to suffer anymore,” he said after resigning with a 16-30 record early in the 1983 season.11

Bamberger returned to manage the Brewers in 1985, but the team was not what it had been. After one poor season and most of a second, he was fired in September 1987 and retired for good.

After baseball Bamberger settled into a life of painting and golf in North Redington Beach, Florida. He died at his home there, after battling colon cancer, on April 4, 2004. He left Wilma, his wife of 53 years; three adult daughters; five grandchildren; three great-grandchildren; and a brother.

Sports Illustrated asked Jim Palmer, who won 20 games in seven seasons under Bamberger’s tutelage, for his memories: “George had flawless mechanics. If I ever got out of sync, I used to visualize him throwing batting practice. But with us — his ‘boys’ — he didn’t preach mechanics. He had a sixth sense of what a pitcher needed to be better, and he knew it could be different for each guy. There were a few hard rules, but everybody was unique, and he understood that. George’s great strength was he didn’t overcoach. There’s no place for panic on the mound.”12

This biography appears in “The Team That Time Won’t Forget: The 1951 New York Giants” (SABR, 2015), edited by Bill Nowlin and C. Paul Rogers III.

Sources

Bob Chick, “Bamberger’s pitching theory was simple but quite effective,” The Tampa Tribune, March 4, 2000.

Clancy Loranger, “Mountie Bamberger steps out as ERA leader — 2.36,” The Sporting News, Sept. 3, 1958.

Tom Hawthorn, “Recalling the Mounties’ major minor legend,” The Tyee, April 26, 2004.

Notes

1 Lowell Reidenbaugh, “Shaky at start, Cuellar finishes like a champ,” The Sporting News, October 31, 1970, 39-40.

2 Ron Fimrite, “Prosit! He’s the toast of the town,” Sports Illustrated, April 30, 1979.

3 Roch Kubatko, “Shepherd with a staff, Bamberger was O’s ace,” Baltimore Sun, April 7, 2004.

4 Richard Goldstein, “George Bamberger, 80, pitching coach, dies,” New York Times, April 7, 2004.

5 Ross Newhan, “He was a workhouse warhorse, very few are left,” Los Angeles Times, July 11, 1993.

6 Denny Boyd, “Let’s talk about baseball’s Bamberger,” Vancouver Sun, April 21, 1980.

7 Denny Boyd, “Let’s talk about baseball’s Bamberger.”

8 Doug Brown, “Oriole hurlers please note: Bauer is sick of sore arms,” The Sporting News, March 2, 1968.

9 Dave Anderson, “George Bamberger, the Brewers Ph.D. in pitching,” New York Times, March 8, 1979.

10 Vic Ziegel, “Bambi Meets the Mets,” New York, March 8, 1982, 55-56.

11 “Inside Pitch,” Sports Illustrated, June 13, 1983.

12 “Arms and the man,” Sports Illustrated, April 19, 2004.

Full Name

George Irvin Bamberger

Born

August 1, 1923 at Staten Island, NY (USA)

Died

April 4, 2004 at North Redington Beach, FL (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.