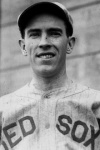

Emmet McCann

His parents, Thomas and Jennie, named him after the Irish nationalist revolutionary Robert Emmet, but added an extra “t.” Thomas came from Ireland. Thomas must have done well earlier in life, or inherited wealth, because he shows up in the United States census as without an occupation and with the designation “own income.” The couple had 10 children – Florence, Frank, Jeannette, Joseph, Thomas, John, and the youngest, Robert Emmett McCann.1 Jeannette became a music teacher, while the others found work as a steward in a club, a shipfitter, a clerk in a gas office. And Emmett played baseball for almost his whole life.

He was born in Philadelphia on March 4, 1902. He died young, not long after turning 35. As far as we have been able to determine, McCann was not a relative of baseball pitcher and contemporaneous minor-league manager (and later scout) Gene McCann or of lightweight championship boxer Billy McCann.

After attending the Harrity School and then graduating from West Philadelphia High School, McCann spent his first year in professional baseball in the Class-C Virginia League in 1919, playing for the Suffolk Nuts. He’d just turned 17. He hit .263 in 105 games, but committed 45 errors – nearly an error every other game, a .925 fielding percentage. He was 5-feet-11, weighed 150 pounds, and batted and threw right-handed. Brothers John, Thomas, Joe, and Frank all played independent baseball in the Philadelphia area.

McCann was invited to spring training with the Philadelphia Athletics in Lake Charles, Louisiana, in 1920, and made the team just a couple of weeks after turning 18. James A. Isaminger of the Philadelphia North American wrote from Donna, Texas, discussing the improvements in the A’s, “Then there is Emmett McCann, the schoolboy prodigy who celebrated his eighteenth birthday March 4. McCann has made good as shortstop on the second team and Mack has decided to keep him for utility roles.”2 Manager Connie Mack had McCann play in the second game of an April 19 doubleheader and he was 1-for-3 with a base on balls, reaching base twice in his debut game. He played shortstop and hit sixth in the order. He started the game on April 20, but committed a simple error in the top of the third: He got to bat only once before he was replaced by Fred Thomas. And then was farmed out to Jersey City, not to return until September 7. He spent most of the year with the Jersey City Skeeters, hitting .305 over the course of 98 games in the International League. He was without a home run.

With the Skeeters McCann had a few big hits, like a two-run single in the seventh on June 24, providing all the runs in a 2-1 win over Rochester. After the Skeeters’ season ended he rejoined Philadelphia. On September 17 in St. Louis, in his third appearance since returning, he earned his first run batted in. There were a lot of runs being scored, 17 by the Browns and 8 by the Athletics. For the season with the Athletics, McCann drove in three runs, and hit for a .265 average. With only 54 chances on defense, he committed five errors, a .907 fielding percentage.

In 1921 McCann spent the full year in the big leagues and appeared in 52 of Philadelphia’s games, backup to Chick Galloway at shortstop. He batted only.223, but his fielding improved to a .949 percentage. McCann drove in 15 runs, only twice exceeding one run in a game. Drawing only four walks all season long, he had a meager .242 on-base percentage. But he impressed people, and veteran sportswriter Isaminger touted him in an August column: “He is a young chap and has a brilliant future in baseball. He is getting better all the time.”3

Beginning in 1922 and for the next four years in all, McCann played first-string baseball for the Portland Beavers in the Pacific Coast League. Portland moved him around defensively. In 1922 he committed a somewhat astonishing 85 errors at shortstop. Although that was in the course of 158 games in the longer PCL season, it still produced a poor .911 fielding percentage. For 1923 and 1924 (after a bit of a holdout in ’24), McCann was moved to second base, where he was much better, with .959 and .964 percentages respectively. And repeated rumors had a number of big-league teams bidding for his services, with Portland holding out for upward of $50,000. McCann struggled in 1923, with a broken finger in May and a broken bone in his leg in August. The Sporting News said he’d been sensation at second base, “as brilliant a performer at the middle station as there is in the league.”4 In 1925 he was moved to the outfield, where he successfully fielded 97 percent of the chances. It was the one and only year he played in the outfield.

McCann was better at the plate, too, batting .280 in his first year with the Beavers and then only once hitting below .300 in his next 11 years in minor-league ball. In 1924 he hit .320 and had 11 home runs, more than the total of his prior years. On September 20, in a nine-inning game against Salt Lake City, he was a record 7-for-7 at the plate.

In February 1925 McCann married Margaret Emma Nelson. They ultimately had two children: Robert Jr. and Peter Nelson McCann. On December 10, 1925, there was a three-way trade that sent McCann to the Boston Red Sox, while Bill Wambsganss went from Boston to Philadelphia Athletics for the waiver wire price of $4,000, and Boston sent Bill Prothro and $4,000 to Portland in order to compensate them for providing McCann.5 The Boston Globe enthused, “McCann is according to all accounts a great second baseman.” He’d been highly recommended to Red Sox owner Bob Quinn by former left fielder Duffy Lewis. It was seen as something of a steal in that the Brooklyn ballclub held an option on him and had planned to give Portland $50,000 and two players, but Brooklyn owner Charlie Ebbets had died in April and matters were confused for a considerable period of time, during which the option had expired.6

Still only 24 years old, McCann opened the 1926 season with the Red Sox, back in the major leagues after five years away. He made the team during spring training in New Orleans, and was determined to make the most of his opportunity.7 His main competition at second base was seen as Cuban native Ramon “Mike” Herrera. Then Topper Rigney was bought from the Tigers on April 7, to firm up the infield, and McCann didn’t get much work at all. He appeared in six games, the last one on May 23, and garnered only four plate appearances. He walked once, but was .000 as a batter. He didn’t score a run and didn’t drive one in. And on May 25, he was traded to the Columbus Senators of the American Association along with Chappie Geygan for their second baseman, Bill Regan, who was hitting .344 at the time. The rookie Regan and Rigney became the main men in the Red Sox’ middle infield.

Just as he had in Portland, once McCann arrived in Columbus, he stuck for a good long time – five seasons. In the remainder of the 1926 season, he hit .337 in 104 games, the best average of his career. That fall his option was purchased by the Washington Nationals but he was returned to Columbus on March 29, 1927. Brooklyn was actively after him, but when the club learned that the terms of the option called for $10,000 to be given to Columbus should McCann still be with a major-league team by May 1, their interest melted away.8 So McCann stayed with the Senators, joining them for the balance of their spring training in Savannah. One spectacular game stood out – in a game against Louisville, McCann was 5-for-5, driving in six runs and scoring four. After the 1927 season, his contract was sold outright to the Cincinnati Reds but on March 21, 1928, he was returned to Columbus. He played full seasons in 1928, ’29, and ’30 and then seemed to leave the game, working in the offseason selling insurance in Philadelphia. Hearing that there was an overall lack of good first basemen in the major leagues, he decided to give it another go.9

In 1928 McCann played most of the season at second base but a few games at first base. In 1929 he played first base in 119 games, and in 1930 practically the full season (151 games), and batted .315. In 1931 the 29-year-old McCann added another line to his résumé, becoming manager of the American Association’s Indianapolis Indians. His arrangement was a little different from the usual player-manager one; McCann had separate contracts as a player and as a manager. The Indians finished third in 1931, a big improvement over their last-place finish the year before. In 1932 they dropped to fifth. After the season, in September, Indianapolis signed Red Killefer to manage the team in 1933. They held off on offering McCann a player contract,10 and on February 11, 1933, he was named manager of the St. Paul Saints.

As St. Paul manager McCann played in 50 games and hit .329. He resigned before the season was over and Phil Todt took the reins as the team finished in seventh place. It was off to Little Rock for 1934; signed to manage the Travelers in January, he didn’t play at all and the team finished in last place in the Southern Association. McCann left early, replaced on June 11 after resigning. His last year in Organized Baseball was in 1935, a mixed one that he began managing the Elmira Pioneers and played in 12 games (batting .319) for the Hazleton Mountaineers – both teams in the New York/Penn League. But something went very badly wrong and in late July McCann suffered a nervous breakdown. He was committed to the Norristown Insane Hospital. He was released in the fall and returned home to live with his wife and their two children.

For reasons unclear to us today, McCann took his own life on April 15, 1937. Police found him shot dead, “a bullet in his brain (and) a discharged revolver nearby,” in Philadelphia’s Cobb Creek Park on the Karakung Golf Course.11 He was just 35 years old. McCann’s career minor-league batting average was .307 over the course of 15 seasons. His grandson, Thomas John McCann, played very briefly – just four games – in rookie ball for the Houston Astros in 1976.

Sources

In addition to the sources noted in this biography, the author also accessed McCann’s player file from the National Baseball Hall of Fame, the Encyclopedia of Minor League Baseball, Retrosheet.org, and Baseball-Reference.com.

Notes

1 Three other children died in infancy – two boys and one girl. E-mail to author from Rita McCann Ritzel, August 10, 2019. Jennie McCann died when he was quite young, on August 10, 1909.

2 Washington Post, March 21, 1920

3 The Sporting News, August 18, 1921

4 The Sporting News, August 23, 1923

5 Los Angeles Times, December 11, 1925

6 Boston Globe, December 11, 1925

7 Boston Globe, March 4, 1926

8 Washington Post, March 30, 1927

9 Washington Post, December 11, 1930

10 Los Angeles Times, September 25, 1932

11 The Sporting News, April 22, 1937. The death certificate indicated “suicide, temp. deran.” His occupation at the time was listed as insurance broker.

Full Name

Robert Emmet McCann

Born

March 4, 1902 at Philadelphia, PA (USA)

Died

April 15, 1937 at Philadelphia, PA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.