Mike Herrera

Were the Boston Red Sox the last major-league team to sign a black player? Or were they one of the first? Did the Red Sox actually have a black ballplayer long before Pumpsie Green and 22 years before Jackie Robinson debuted with the Dodgers? Havana’s Ramon “Mike” Herrera totaled 276 at-bats in 1925 and 1926 while serving as a second baseman for the Red Sox (an even .275 batting average). He also played for Negro League teams both before and after his stretch with Boston, one of just 11 players who played in both the Negro Leagues and major leagues before World War II.

Before joining the Red Sox, Herrera had played for Almendares in Havana, as well as with La Union, All Leagues, and the (Cuban) Red Sox. The Boston Red Sox purchased him from their Springfield (Eastern League) club. The Boston Globe termed him a “splendid prospect” and he did go 2-for-5 in his first game. Negro Leagues historian Todd Bolton, asked about Herrera’s history in the Negro Leagues, replied: “In the pre-Negro League years he barnstormed in the US with the Long Branch Cubans and the Jersey City Cubans. When the first Negro National League was formed in 1920, Herrera was a member of the Cuban Stars (West), one of the inaugural teams in the league. He stayed on with the team in 1921 when it became the Cincinnati Cubans. Herrera returned to the Negro Leagues for one final season in 1928 with Alejandro Pompez’ Cuban Stars (East).”

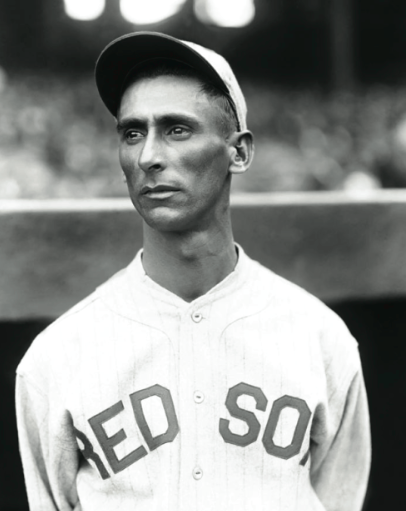

Photographs of Mike Herrera seem to show that he could easily “pass” for white, and for those who want to measure such things, he may have been more white than black. So did he have to “pass for black” when he was in the Negro Leagues? Not really, Bolton explained. There were a number of light-skinned players in the Negro Leagues and even more “white” Cubans. These players were used to playing together in Latin America. It was only in the United States that they were segregated. Herrera was one of 16 Cubans listed by Pete Bjarkman as having played in both the major leagues and the Negro Leagues. [Bjarkman, A History of Cuban Baseball, 1864-2006, McFarland, 2007, p. 134] Ocania Chalk, author of Pioneers of Black Sport: A Study in Courage and Perseverance, states that Herrera “has been verified as a black“ – however this is determined. [Unattributed clipping in Ramon Herrera player file at the National Baseball Hall of Fame]

Ramon Herrera was a right-handed infielder of small stature (5-feet-6, 147 pounds) born in Havana on December 19, 1897. Perhaps. Gary Ashwill studied all his declarations of age on passenger manifests for ships coming and going to the United States and found four different years of birth cited, ranging between 1889 and 1894 – every one of them significantly older than an 1897 birthdate.

His first appearance in Cuban pro ball was over the winter when he turned 17, when he played second base with Almendares under manager Eugenio Santacruz. It wasn’t much of a start, but he played in 27 of the team’s 33 games, garnering 84 at-bats though only a .172 average in the 1913-14 season; but he was on his way. His average was middle of the pack among the team’s infielders that year. Almendares came in first in the three-team league. The following year (1914-15) Herrera played third base for last-place Fe, hitting .289 in 121 at-bats, second best among the infielders. Taken back by Almendares in 1915-16, he played this time under Alfredo Cabrera, his third manager in three seasons. Herrera was back at second base.

Herrera seems to have played ball in the United States at least a couple of times. In 1916, he played for the Long Branch Cubans in a game in New York, beating the Cuban Stars of New York, 5-4, in a “sensational fielding game,” according to the next day’s Chicago Defender. He was 0-for-3 at the bat, but handled seven chances without an error. The year before, a player named Herrera played shortstop for the Havana Reds on July 23 and collected five hits in the game. The player’s first name was not given in the Defender’s account but there is no other Herrera listed in Cuban baseball records of the era.

Bizarrely, in 1917, Herrera played for the Red Sox – but this wasn’t the Boston team. The old Habana ballclub had taken on the name for the short 14-game season in January and February which was all that remained of the season following acrimonious battles between players and management over issues of compensation. Herrera played second base again, but hit just .167 in his 54 at-bats. During the November 1918 to March 1919 season, Herrera played for Almendares for a third time, but there are no statistics available for either him or the team’s other second baseman, E. Rivas. Herrera stuck with Almendares through the 1923-24 season but now started alternating good and mediocre seasons, hitting .300, .141, .350, .278, and .299. He was supplanted at second base by Eusebio Gonzalez in 1920-21; Gonzalez had appeared in three major-league games for the Boston Red Sox in 1918 and was an established ballplayer in the American minor leagues by this time. Herrera still got in as many at-bats, but apparently played more outfield than infield. He even pitched 6 2/3 innings, allowing eight hits and walking three but without a decision in 1921.

Gary Ashwill said Herrera first played minor-league ball for the Bridgeport Americans in 1922, but moved on to the Springfield Ponies early enough in the season that his record with Bridgeport doesn’t show up in such Eastern League records as we have for the year. He was apparently known by two nicknames, one Cuban (Paito) and one in American ball (Mike). In 1922, the Ponies featured Herrera in some 83 games. He hit.276 and got his first recorded professional home run. The first box score we have found shows him going 0-for-3 but praised for “fine fielding” in the August 2 Hartford Courant as the Hartford Senators whipped the Ponies, 10-0, a two-hitter. After the season, Herrera kept playing ball, working again for Almendares, reclaiming the starting second baseman’s position and hitting .278. Herrera was occasionally described as “Springfield’s Cuban second baseman” but no trace of pejorative language has been found in the newspapers of the day.

In 1923, Herrera showed a flash of power not seen before or subsequently, banging out 15 home runs along with seven triples on his way to a career-high .354 average, up considerably over 1922’s .276. The Courant’s game account on August 23 began its second paragraph, “Senor Herrera, the swarthy-faced gentleman from the land where there is no prohibition.” Herrera led off the game with a home run. There is an indication that some were well aware Herrera was not pure Castillian ancestry; A.S. “Doc” Young, writing for Ebony magazine in November 1968, recalled “a story in Boston about a ‘Cuban Negro’ named Ramon Herrera who allegedly had played with the Red Sox in the middle 20’s.”

Herrera came back to Springfield and played a full season of 152 games in 1924, hitting .303 despite an abbreviated spring training (he’d written to manager Dave Shean from Havana that he didn’t like the cold so would appear on the day preseason play began, but that he was in solid baseball shape with winter ball in Cuba.)

In 1924-25, Herrera moved over to Habana and played second base on a team featuring future Cuban Baseball Hall of Famers Martin Dihigo and Cristobal Torriente. After hitting .337 for the Springfield Ponies in his fourth Eastern League season, Herrera was asked to join the Boston Red Sox in mid-September. The Sox bought his contract from Springfield on September 15 and the September 21 Boston Globe heralded his arrival, noting that he was second in hitting in the Eastern League and first in sacrifice hits, and had stolen 26 bases. He debuted on September 22 and was 0-for-4 in the day’s first game and 2-for-5 (both singles) in the second. He committed one error. The New York Times mentioned him in a subhead on October 2: “Herrera, Boston Recruit, Stars.” Ramon had gone 3-for-4 and stolen a base. The Associated Press story noted his “spectacular playing.”

In 10 games, Herrera drove in eight runs for the Red Sox with a .385 average, his 15 hits all singles. Boston sportswriter Burt Whitman wrote in The Sporting News (under the headline “Boston’s Cuba Prospects Boosted”) of pitcher Oscar Estrada and Herrera that he’d been told by a knowledgeable Cuban sportsman that Herrera “is a great hitter, even if he does not develop into a high-grade and steady performer at second base. … Mike is a natural hitter and would be worth more than his salt to any team in either big league if used for nothing else but his pinch-hitting prowess.” Most impressive was his batting average of .385 against Adolfo Luque in Cuba. [The Sporting News, October 22, 1925]

Herrera joined Boston for spring training in 1926 and earned himself a few headlines during the exhibition season. He was named on March 31 by manager Lee Fohl as the team’s starting second baseman, having beaten out Emmett McCann for the keystone slot. He doubled in the second of two games on Patriots Day in Boston’s 2-1 win over the Athletics. By May, Burt Whitman was writing that “his hitting is as good and as dependable, at least, as any other player on the team.” [The Sporting News, May 13, 1926] On June 6, in the bottom of the eighth in Chicago, the second baseman snagged Bibb Falk’s liner, fired to first, and kicked off a triple play that squelched a White Sox rally to enable Boston to win, 4-3. The Red Sox had until June 15 to return Herrera to the Ponies, but he was acquitting himself well and Red Sox owner Bob Quinn elected to keep him. He turned in his best day at the plate on August 25, 2-for-3 while driving in three runs.

Herrera’s last game in the majors turned out to be the first anniversary of his debut game, September 22. He batted leadoff, and was 0-for-4. On December 9, Herrera was released to Mobile. The Boston Globe summed up his time with the Red Sox, saying he was given a thorough trial at second base, and also at third. (He also played shortstop in a few games.) Herrera looked as if he might become a fair batsman, but was not as satisfactory as a second sacker. He was pretty good in straightaway fielding, but when he participated in an attempted double play, whether starting it or acting as a relay man, his play was a failure nine times out of 10. There was nothing in his work at the hot corner, in the few games he played there, to justify a hope that he would make a big-league third baseman.” The Globe’s James C. O’Leary surmised that Quinn kept an option to recall Herrera from Mobile if he started coming around in 1927. While he hit .383 for Habana (his third straight Cuban season over .300), playing in the Southern League with Mobile, he hit only 214 in 56 games of Class A ball. On June 24, he was placed on waivers by the Bears and sold back to Springfield. Back with the Ponies again, he hit .243 and completed his final season in North American minor-league baseball. As noted above, Herrera returned to the Negro Leagues for one final season in 1928 with Alejandro Pompez’ Cuban Stars (East). He doubled and scored the winning run in the top of the 16th in a long battle against Harrowgate on July 7. He seems to have tried out for the Pueblo Steelworkers in the Western League, but whether he ever reported is undetermined. [See a mention of his intent in the February 7, 1929 Sporting News.]

The 1929-30 season was Herrera’s last in Cuban ball, again with Habana, and he closed out his career with a strong .322 average. His 18 seasons of Cuban baseball left him with a .291 batting average.

As with a number of Cuban ballplayers who were on the island when the Revolution occurred, the details of the last 50 years of Herrera’s life remain unknown. He was named to the Salon de la Fama del Deporte Cubano (Cuban Baseball Hall of Fame) in 1963, the year after elections to the Hall were transferred to Miami. Herrera died in Havana on February 3, 1978, and is buried in the Christopher Columbus Cemetery of Havana.

A version of this biography appeared in “Cuban Baseball Legends: Baseball’s Alternative Universe” (SABR, 2016), edited by Peter C. Bjarkman and Bill Nowlin.

Sources

Ashwill, Gary. Website at www.agatetype.com

Bjarkman, Peter. A History of Cuban Baseball, 1864-2006. Jefferson, NC: McFarland, 2007.

Figueredo, Jorge S. Cuban Baseball: A Statistical History, 1878-1961. Jefferson, NC: McFarland, 2003.

_____. Who’s Who in Cuban Baseball, 1878-1961. Jefferson, NC: McFarland, 2003.

In addition to the sources cited in this biography, the author consulted the online SABR Encyclopedia, retrosheet.org, and Baseball-Reference.com.

Full Name

Ramon Herrera

Born

December 19, 1897 at La Habana, La Habana (Cuba)

Died

February 3, 1978 at La Habana, La Habana (Cuba)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.