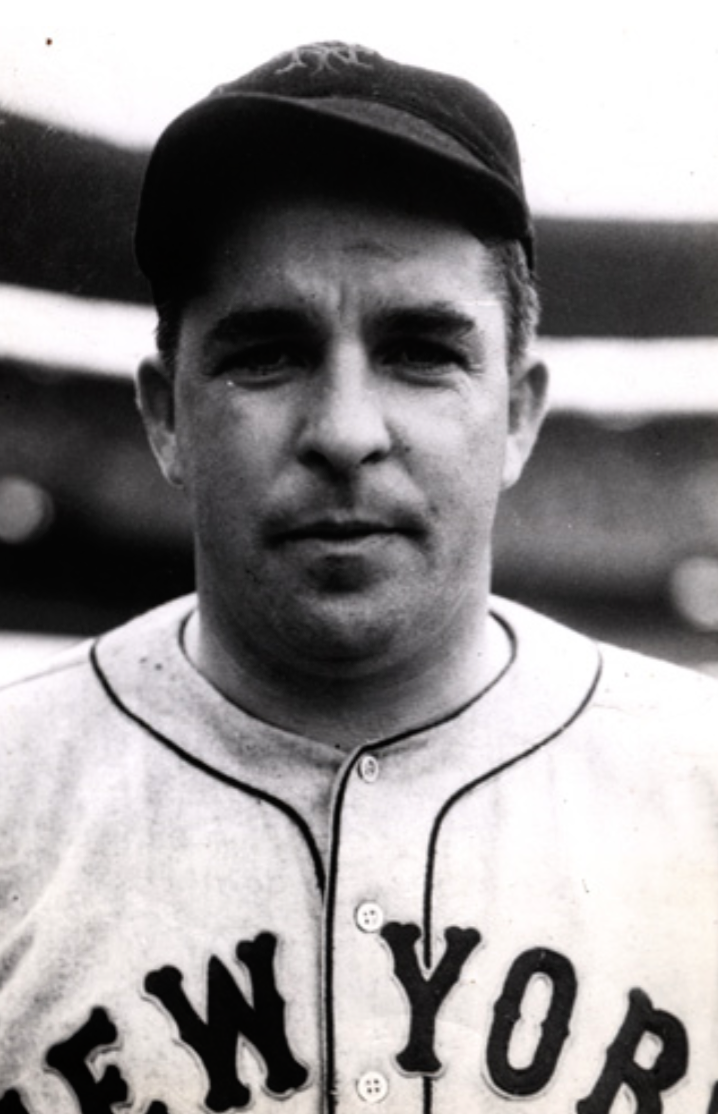

Freddie Fitzsimmons

With his short arms and legs, long torso, and ample midsection, right-hander Fat Freddie Fitzsimmons may not have looked like a major-league pitcher during his 19-year career with the New York Giants and Brooklyn Dodgers from 1925 to1943. But with one of baseball’s most effective knuckleballs and a deceptive, whirling delivery, he won 217 games. One of the era’s most popular players and arguably the best fielding pitcher (despite his size), Fitzsimmons helped lead the Giants to the World Series in 1933 and 1936 and the Dodgers in 1941. A baseball lifer, Fitzsimmons managed the Philadelphia Phillies (1943-1945) and served as a respected coach for multiple teams, most notably on the Giants’ pennant-winning teams in 1951 and 1954.

Frederick Landis Fitzsimmons was born on July 26, 1901, in Mishawaka, Indiana (about five miles east of South Bend). His parents, Robert Oscar and Margaret Ellen (Gordon) Fitzsimmons, native Hoosiers, named their first son (their second of five children) in honor of Henry Landis, a newspaper editor in Indiana (and no relation to future baseball commissioner Kenesaw Landis). Young Freddie received his first instruction in baseball from his father, a former sandlot player who rose to the rank of chief of police in the town. But despite growing up in the heart of football country and in the shadow of the University of Notre Dame, Freddie idolized legendary shortstop Honus Wagner and dreamed of becoming a big-league infielder while attending Battell grammar school and spending his summers playing ball on an uncle’s farm in the southern part of the state. When he was about 15 years old, he learned to throw the knuckleball from another youngster, fell in love with the dastardly pitch, and decided to become a pitcher. After local semipro pitcher High Pockets Daniels helped him learn to control the knuckler, Fitzsimmons soon made a name for himself in sandlot leagues and graduated to more competitive semipro leagues. “I didn’t play any ball in high school,” he recalled of his two years at Mishawaka High School, “because those factory teams were after me and I had to train and work out for them.”1

Fitzsimmons’ big break came in 1920 when he pitched against Carl “Skinny” Blackmore in a semipro game in Mishawaka. Blackmore, who also played for the Muskegon (Michigan) Muskies of the Class B Central League told his manager, Doc White, about the knuckleballer, whom the team then invited for a tryout. Without informing his father, who wanted his son to maintain his steady job in a local woolen mill, Fitzsimmons paid his own expenses and traveled to Muskegon, about 140 miles away, and made the team. He beat the eventual league champion Grand Rapids Joshers in his first game, and went on to pitch 12 consecutive complete games, winning three of them and posting a 3.69 ERA. Armed with his crafty knuckleball and an assortment of breaking balls, the 5-foot-11, 175-pound righty (he had not yet acquired the “Fat Freddie” sobriquet) proved to be a durable hurler, logging almost 500 innings and winning 30 games in less than two years for a mediocre Muskegon club before the Indianapolis Indians of the American Association bought his contract near the end of the 1922 season for a reported $3,900.

Fitzsimmons spent almost three years playing with the Indians and getting accustomed to facing mature hitters, many of whom had or would have major-league experience. After winning three of seven decisions following his arrival in Indianapolis, Fitzsimmons carved out a 9-4 record in 1923 as a spot starter, and then came into his own the next two seasons under manager Donie Bush. He won 14 games and logged 279 innings (fifth-best in the league) in 1924, followed by an outstanding 14-6 record in less than a full season in 1925. The highlight of his final season in the minor leagues may have been an outing against the Milwaukee Brewers, in which he yielded a double on the first pitch of the game and then retired the next 27 batters to notch his only career one-hitter.

Fitzsimmons’ transformation into one of the best young pitchers in the American Association came at a prescient moment. The New York Giants, winners of the previous four NL pennants, got off to another hot start under manager John McGraw in 1925, but their pitching wilted in June and July. On team scout Dick Kinsella’s recommendation, McGraw went to Indianapolis to personally scout Fitzsimmons, who had bewildered the Giants in an exhibition game in Plant City, Florida, during spring training. On August 8 the Giants acquired Fitzsimmons for a reported $50,000.

Fitzsimmons saw his first major-league game the day he reported to the Giants. Thrown into a pressure-packed pennant race, he made his major-league debut on August 12, relieving Virgil Barnes and hurling four scoreless frames in a 5-3 loss to the eventual World Series champion Pittsburgh Pirates at Forbes Field. Four days later Fitz (as his teammates and reporters typically called him throughout his big-league career) made his first start, a complete-game victory over the Boston Braves at the Polo Grounds. One of the most consistent Giants pitchers over the last six weeks of the season, Fitzsimmons won six of nine decisions, completed six of eight starts, including the first of 30 career shutouts (a four-hitter against the Pirates), and posted a team-best 2.65 ERA.

Fitzsimmons won 14 and logged 219 innings for the fifth-place Giants in his first full season in the big leagues to commence an impressive streak of nine consecutive seasons of at least 200 innings. Overshadowed by other pitchers from his era (such as Charlie Root and Pat Malone of the Cubs, Dazzy Vance of the Dodgers, and later Dizzy Dean of the Cardinals and Giants teammate Carl Hubbell), Fitzsimmons was one of the most durable and successful pitchers of his era, averaging 242 innings and 16 wins per season from 1926 to 1934.

Fitzsimmons’ success rested with his knuckleball. “My knuckleball kind of acted like a spitter so people called it a ‘dry-spitter,’ ” he said. “It broke down the same way as a spitter. Catchers didn’t have any trouble catching me even though they didn’t have big gloves.”2 In his first game as a professional pitcher with the Muskies, the opposing manager protested continually that Fitzsimmons threw a spitter, a charge he would face for years to come. Unlike other traditional knuckleballers of the times (Eddie Rommel or Jesse Haines), Fitzsimmons gripped the ball with two fingers (his index and middle fingers); when he threw the pitch, he pushed his fingers forward, resulting in a fast knuckler with uncanny movement. The Sporting News considered it a “freak pitch even in knuckleball circles.”3 Bill James and Rob Neyer refer to Fitzsimmons’ knuckleball as a “knuckle-curve” much like what Burt Hooten of the Chicago Cubs threw in the early 1970s.4 The burly right-hander also had an above-average fastball and a curveball.

Because of his unusual control of the knuckleball, Fitzgerald could use the pitch no matter what the pitch count to surprise the hitter. He walked just 846 batters in 3,223⅔ innings for an average of 2.4 bases on balls per nine innings. (For perspective, Lefty Grove walked 2.7 per nine innings.) “It all depends,” he said when asked how often he threw his knuckeball. “Some days I throw a hundred balls up there [and] maybe fifty of ’em would be a knuckler.”5 As with any pitch, the element of surprise was key. “When you were expecting a low breaking knuckleball that high fast one would come in,” said catcher Gabby Hartnett, “and you wouldn’t be ready to hit it. [Fitzsimmons] was a whiz at giving you the pitch you weren’t looking for.”6

Described as a “whirling dervish,” Fitzsimmons’ unorthodox delivery disconcerted hitters who were unable to pick up the ball.7 Manager Donie Bush of the Indianapolis Indians suggested that Fitzsimmons throw with a whirl-around motion to hide the ball. The result was that Fitzsimmons started his delivery facing center field then twisted around, much like Luis Tiant five decades later, and released the ball from multiple angles (from overhand, three-quarters, and side-arm to underhand) to confound hitters. “I never kept my eyes on home plate,” said Fitzsimmons, who years later as a pitching coach had difficulties teaching his hurlers to do the exact opposite.8 “Take [my delivery] away from me and I wouldn’t gamble on my success,” he said. “That’s how important I rate it.”9 According to the pitcher, he threw the knuckler equally to right- and left-handed hitters, but noted that his side-arm knuckler broke like a curve while from an overhand or three-quarter delivery it broke straight down. In his autobiography Nice Guys Finish Last, Leo Durocher offered perhaps the most visually descriptive account of Fitzsimmons on the mound: “If you ever saw Freddie pitch, you could never forget him. He would turn his back completely to the batter, as he was winding up, wheel back around and let out the most god-awful grunt as he was letting the ball go — rrrrrhhhhhooooo — like a rhinoceros in heat.”10

As a green rookie, Fitzsimmons was shocked by manager John McGraw’s public berating of players in the clubhouse, yet the pitcher overcame these outbursts to become a fierce and fearless competitor on the field, willing to throw inside (and occasionally at a batter) in order to establish his control of the plate. The Giants retooled from their glory days (1921-1924) by adding first baseman Bill Terry, shortstop Travis Jackson, and third baseman Freddy Lindstrom, as well as second baseman Rogers Hornsby, and were the NL’s highest scoring team in 1927. They struggled, however, for much of the season under McGraw, who took a leave of absence with 32 games remaining just as the club began to play better. On Fitzsimmons’ broad shoulders the Giants (now managed by Hornsby) crept back into the pennant hunt the last month of the season. Fitzsimmons made seven starts, relieved three times, and won five of his 17 games in that fateful month. His victory in relief of Virgil Barnes against the eventual pennant-winning Pirates on September 24 brought the team to within 1½ games of the lead, but the Giants ultimately finished in third place, an agonizing two games behind the Pirates.

Fitzsimmons won 20 games for the first and only time of his career in 1928 with McGraw once again in the dugout. In a repeat performance from the previous campaign, the Giants played sluggishly for most of the season, but caught fire in the last month, winning 25 of 33 games to battle the St. Louis Cardinals for the NL crown. Starting eight times in September (many of his starts on short rest), Fitzsimmons won three games in a span of five days, culminating with a ten-inning complete-game victory on September 18 over the Pirates. But the Giants lost three of their final five games to finish in second place.

Fitzsimmons posted records of 15-11, 19-7 (with a league-leading .731 winning percentage), and 18-11 as the Giants finished in third place twice and second place once from 1929 to 1931. He endeared himself to fans and teammates alike for his hustle, positive attitude, and willingness to play through injuries. Highlights of these seasons include hurling four shutouts against the Cincinnati Reds in 1929 and completing six consecutive starts, winning five of them plus another in relief) in the last month of the 1930 season to keep the heat on the eventual pennant-winning Cardinals.

Fitzsimmons gradually acquired the affectionate nickname Fat Freddie by the late 1920s as his weight increased to 215 pounds if not more. Wearing a perpetual smile, Fitzsimmons was dark-complexioned (often referred to as a Black Irishman) with jet-black hair parted down the middle, dark blue eyes, and a deep voice.11 Newspaper accounts of the times described him as the most popular Giants player of the era and as having an emotional connection with Giants fans that few players ever had. Humble, approachable, and outgoing, Fitzsimmons avoided the nightlife New York City offered and neither drank nor smoked cigarettes. He was seen constantly with his wife, Helen (née Borger), whom he met while playing in Indianapolis and married after his rookie season. Described by The Sporting News as the “most devoted couple in the majors,” the Fitzsimmonses had one child, also named Helen, who like her mother was a common fixture at spring training.12 Wife Helen was a diehard baseball fan who celebrated her husband’s accomplishments, but suffered equally his personal and team disappointments. During the offseason, the photogenic couple lived on a farm in Arcadia, California, outside of Los Angeles, where they raised chickens in prosaic surroundings. Later they moved to Yucca Valley, north of Palm Springs. “There isn’t a finer character in baseball,” wrote nationally syndicated columnist Dan Daniel, offering perhaps the greatest compliment to Fitzsimmons. “And there isn’t a more straightforward hombre pitching, catching, batting, or doing anything in this grand game of ours.”13

Fat Freddie was considered the best fielding pitcher of his generation. He possessed uncanny reflexes, agility, and quickness off the mound, and had unparalleled range.14 Despite his short legs and arms (Casey Stengel nicknamed him the Seal because his arms gave the impression of flippers), Fitzsimmons was often described as a fifth infielder, who regularly knocked down liners back to the mound with his hand, glove, legs, and even chest in order to save a hit.15 Along the way he suffered bruises and well-publicized incidents of being knocked out after being hit in the throat, head, and groin. “It’s the little things that lose a lot of ballgames,” Fitzsimmons once said about the art of fielding for pitchers. “Proper fielding of a slow ball rolling near the box sometimes means the difference between a loss and a victory.”16 Fitzsimmons admitted that his fielding helped make him into a good pitcher, but noted that it takes practice, patience, and above all desire to be a good fielder. “The most important thing is hustling in pepper games as if you are in an actual game,” he said.17 He was among the top five in putouts nine times, leading the league four times, while placing in the top four in assists seven times (he led once), and retired among the career leaders in both categories.

A watershed moment in New York Giants history occurred in 1932 when Bill Terry replaced McGraw as manager of the storied club. After years of frustrating losses and near-misses, Fitzsimmons noticed how the players had begun to bristle under the dictatorial leadership of McGraw, aptly nicknamed Little Napoleon. “McGraw’s abuse antagonizes so many men that their refusal to play for him eventually led to his resignation,” Fitzsimmons said, unsurprised by the move.18 He welcomed Terry as the new manager, yet like the rest of his team, was mired in a collective slump, and finished with an 11-11 record, his only nonwinning record in his first ten years in the big leagues.

Terry led what sportswriters considered an average team in 1933 to the NL pennant behind the exceptional pitching of Fitzsimmons (16-11), Hal Schumacher (19-11), and especially Most Valuable Player Hubbell (23-12). Facing the Washington Senators, who had broken the New York Yankees and Philadelphia Athletics’ seven-year hold on the AL pennant, the Giants held Washington to just 11 runs to win the World Series in five games. After years of waiting for his time on the national stage, Fat Freddie pitched adequately in Game Three at Griffith Stadium, surrendering nine hits and four runs, but Earl Whitehill held the Giants scoreless, making Fitzsimmons a tough-luck loser, 4-0.

The agony of losing the pennant on the last weekend of the season in 1934 was eclipsed by Fitzsimmons’ first major arm woes in 1935. Given extra rest between starts in the first half of the season, Fitzsimmons won four of eight decisions through June. Oddly, all four victories were shutouts, which led the league. But the pain soon became unbearable and the courageous veteran missed almost all of July and August after surgery to remove adhesions and cartilage buildup. The operation marked the end of Fitzsimmons’ career as a front-line starter capable of pitching every four or five days. He won only 59 more games during the remainder of his career (1936-1943).

Fitzsimmons came down with a severe streptococcal infection in 1936. According to The Sporting News, it “almost cost him his life” and weakened him the first half of the season.19 Beginning on July 28 and culminating with a 13-inning duel with the Pirates’ Waite Hoyt on August 28, Fitzsimmons won six consecutive starts to lead the Giants from an eight-game deficit into a three-game lead over the Cubs. He tossed three more complete-game victories in September to help the Giants capture another NL pennant and secure his spot in the starting rotation for the World Series. In the first all-New York World Series since the clubs’ meeting in 1924, the Giants (92-62) were prohibitive underdogs against the New York Yankees (102-51). With the Series tied at one game apiece, Fitzsimmons pitched brilliantly in Game Three, holding the Yankees to two hits and one run through seven innings. Then Frank Crosetti hit a chopper back to the mound with two out and men on first and third in the eighth inning. As Fat Freddie had done countless times in his career, he knocked the ball down with his gloved hand, but as fate would have it, the ball rolled away as the Yankees’ Jake Powell scored the deciding run in a 2-1 game. In Game Six, the 35-year-old looked his age as the vaunted Yankees sluggers pounded him for nine hits and five runs in 3⅔ innings to capture the title.

With just 14 victories the previous two years and the memory of his loss in Game Six still fresh, the 35-year-old Fitzsimmons got off to a poor start in 1937, leading the Giants to believe he was washed up. Rumors swirled that he would take a coaching position with the team, but the veteran was instead unexpectedly shipped to the Brooklyn Dodgers for 24-year-old relief pitcher Tom Blake on June 11. Roundly criticized in the press as an insult to a player in his twilight, the trade proved to be a coup for the Dodgers. While Blake won just one game for the Giants, Fitzsimmons, who had terrorized Brooklyn throughout his career, posting a 33-15 record against them, quickly became a fan favorite, tossing complete-game victories in his first two starts. (The Dodgers could have purchased Fitzsimmons’ contract in 1925, but team scout Spencer Abbott suggested otherwise.20)

A once-a-week pitcher for the long-suffering Dodgers, Fitzsimmons was a solid contributor. In 1938, the cagey veteran was arguably Brooklyn’s best pitcher, posting an 11-8 record for the seventh-place team. He topped 200 innings for the tenth and final time and completed eight of his final ten starts, including seven consecutive wins, to lower his ERA to 3.02 (sixth-best in the league). When Fitzsimmons slipped to 7-9 in 1939 for first-year manager Leo Durocher, the press churned out reports that he would retire to become a coach. Durocher, however, persuaded him to return to the team, which had just enjoyed its best season in almost a decade.

In a magical, fairy-tale-like season, the 38-year-old Fitzsimmons turned back the hands of time to post a 16-2 record in 1940. In the second game of a doubleheader at Forbes Field on July 14, he blanked the Pirates on four hits to become just the 11th pitcher since 1900 to win 200 games in the NL. Even more importantly, the Dodgers proved to be serious pennant contenders, battling the Cincinnati Reds for the NL lead for most of the season before finishing in second place. Fitzsimmons was praised for fostering a winning attitude and sense of camaraderie on the team. “Fred’s spirit is one of the vital forces on the club,” wrote Dan Parker in the New York Journal-American.21 As enthusiastic as a rookie and possessing an unmatched work ethic, Fitzsimmons was a de-facto coach who generously shared his knowledge of pitching and opposing players with teammates. Accolades poured in all season. He was chosen as the ideal father in Organized Baseball on Father’s Day, and in a contest sponsored by The Sporting News, fans across the country voted him their favorite big-league veteran.22 He concluded the season by winning his last seven decisions to finish with an .889 winning percentage, a new post-1900 record (since broken by Roy Face in 1959), and an impressive 2.81 ERA. In 1875 two Boston Red Stocking pitchers, Al Spalding (54-5) Jack Manning (16-2), posted winning percentages of .889 or better, and in 1929 Tom Zachary of the New York Yankees went undefeated (12-0).

Pitching more than 3,000 innings had taken a toll on Fitzsimmons’ arm. In constant pain during his last few seasons, his elbow swelled and his arm seemed to curl up after each outing, making it impossible to hold a ball for several days. “[Fitz’s] arm was so crooked,” said Durocher, “that he literally could not reach down and pick anything up. … [His arm] threw him off balance and gave him a rolling, swinging gait.”23 In spite of the pain, Fitzsimmons was reinvigorated after his success in 1940 and returned to the Dodgers in 1941. Described as “courageous” and pitching with “sheer determination,” Fitzsimmons started only 12 times all season but made them count in another heated pennant race.24 He blanked the Braves on August 10 for his fifth consecutive victory of the season (and 11th over two seasons). On September 11 at Sportsman’s Park in St. Louis, he hurled ten inspirational innings against the Cardinals and earned his sixth and final victory of the season when Dixie Walker singled home two runs in the 11th inning.

In a situation reminiscent of 1936, Fitzsimmons faced the New York Yankees in Game Three of the 1941 World Series with the Series tied at one game apiece. Fitzsimmons pitched brilliantly, yielding just four hits and no runs through seven innings. With two outs in the seventh, pitcher Marius Russo smashed a liner back to the mound, hitting Fitzsimmons in the left kneecap. Fitzsimmons limped off the mound, his season over. The Yankees scored two runs off Hugh Casey in the eighth inning to win the game 2-1. They then closed out the Series in five games.

The injury, coupled with age, effectively ended Fitzsimmons’ pitching career. He served as a Dodgers coach in 1942 and took the mound just once. He returned in 1943 to make nine more appearances, including seven once-a-week starts, but was released in mid-July in order to take over as manager of the Philadelphia Phillies. An ultimate competitor, but rarely the topic of Hall of Fame discussions, Fitzsimmons made the most of his natural ability to win 217 games in his 19-year big-league career.

Fitzsimmons’ major-league managerial career lasted only 286 games for the talent-poor Phillies. With the team mired in last place and rumors swirling that team owner William D. Cox was betting on the team (he was eventually suspended in November), Fitzsimmons resigned in late June 1945 “nearing a breakdown.”25 He also managed in the minor leagues on three different occasions (1953, 1956, and 1961) for three different organizations.

After serving on the Boston Braves’ staff during their pennant-winning season in 1948, Fitzsimmons was mired in a controversy when he accepted Leo Durocher’s offer to join the Giants’ staff in 1949. Commissioner Happy Chandler ruled that Durocher had tampered with Fitzsimmons, who was legally under contract with the Braves. He fined Fitzsimmons $500 and suspended him for one month, but recognized the validity of his contract with his new team.

Fitzsimmons was considered a consummate and patient teacher during his seven years (1949-1955) as a Giants coach. During the pennant-winning seasons of 1951 and 1954, the staff led the National League in ERA. “We started out so late and so far back,” said Fitzsimmons of the 1951 Giants, who trailed the Dodgers by 13 games on August 11. “It was completely cockeyed and crazy to think that we even had a chance, but that team had an overwhelming sense of confidence that carried it on a cloud for six weeks.”26 Fitzsimmons also coached for the Chicago Cubs (1957-1959) and the Kansas City Athletics (1960) before returning to the Cubs for an abbreviated stint on Durocher’s staff in 1966.

Fitzsimmons retired with his wife, Helen, to Yucca Valley, where he enjoyed an active outdoor life and occasionally scouted. At the age of 78, he died of a self-inflicted gunshot wound to the head on November 18, 1979. He was cremated and the ashes buried at the Montecito Memorial Park in Colton, California.27

Sources

Carmichael, John P., ed. “Fred Fritzsimmons as told to John P. Carmichael,” My Greatest Day in Baseball (New York: A.S. Barnes, 1945; reprint University of Nebraska Press, 1996), 108-114.

Durocher, Leo, and Ed Linn, Nice Guys Finish Last (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1998).

James, Bill, and Rob Neyer, The Neyer/James Guide to Pitchers: An Historical Compendium of Pitching, Pitchers, and Pitches (New York: Fireside, 2004).

Kahn, Roger, Memories of Summer: When Baseball Was an Art, and Writing About It a Game (Lincoln, Nebraska: University of Nebraska Press, 2004).

Stout, Glenn, and Richard A. Johnson, The Dodgers: 120 Years of Baseball (New York: Houghton Mifflin, Harcourt, 2004).

Thomson, Bobby, The Giants Win the Pennant! The Giants Win the Pennant! (New York: Citadel, 2001).

Williams, Peter, When the Giants were Giants: Bill Terry and the Golden Age of New York Baseball (New York: Algonquin Books, 1994).

Chicago Tribune

New York Times

The Sporting News

Ancestry.com

BaseballLibrary.com

Baseball-Reference.com

Retrosheet.org

SABR.org

Freddie Fitzsimmons player file, Baseball Hall of Fame, Cooperstown, New York.

Notes

1 Eugene Murdock, “He Turned Rockne Down,” in Baseball Players and Their Times: Oral Histories of the Game, 1920-1940 (Westport, Connecticut: Meckler, 1991), 250.

2 Ibid.

3 The Sporting News, October 31, 1940, 5.

4 Bill James and Rob Neyer, The Neyer/James Guide to Pitchers: An Historical Compendium of Pitching, Pitchers, and Pitches (New York: Fireside, 2004), 205.

5 John Kieran, “Sports of the Times,” New York Times, July 16, 1935, 14.

6 Edward T. Murphy, Baseball Magazine, November 1940, quoted in Bill James and Rob Neyer, The Neyer/James Guide to Pitchers: An Historical Compendium of Pitching, Pitchers, and Pitches, 205

7 The Sporting News, October 31, 1940, 5.

8 Eugene Murdock, 250.

9 F.C. Lane, “Freddy Fitzsimmons and His Freak Wind-Up,” Baseball Magazine, June 1935, quoted in Bill James and Rob Neyer, The Neyer/James Guide to Pitchers: An Historical Compendium of Pitching, Pitchers, and Pitches, 205.

10 Leo Durocher and Ed Linn, Nice Guys Finish Last (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1998), 145.

11 The Sporting News, February 19, 1931.

12 The Sporting News, May 9, 1940, 4.

13 Eugene Murdock, “He Turned Rockne Down,” 250, 262.

14 Bill James’ “range factor,” a metric used to evaluate the quality of defensive play, underscores that Fitzsimmons was easily one of the best pitchers of his generation; Fitzsimmons led the league for five consecutive years (1930-1934) and six times (1938) in range factor.

15 Tom Meany, “Crooked Arms Not All On Southpaws — Fitz Has One,” [unattributed article], June 9, 1943. Player Hall of Fame file.

16 John Drebinger, “Fitzsimmons Toils in Fielding Drills,” New York Times, February 27, 1929, 28.

17 Stanley Frank, “Fitz’s Fielding is Key to Hall of Fame Niche,” New York Post, July 3, 1937. Player Hall of Fame file.

18 Peter Williams, When the Giants Were Giants: Bill Terry and the Golden Age of New York Baseball (New York: Algonquin Books, 1994), 241.

19 The Sporting News, October 1, 1936, 4.

20 Charles E. Parker, “Scout’s Guess 12 Years Ago Beat Dodgers in 33 Games,” New York Telegram [no date, 1937]. Player’s Hall of Fame file.

21 Dan Parker, “Fitz Deal Terry’s Greatest Blunder,” New York Journal-American, July 30, 1940. Player’s Hall of Fame file.

22 The Sporting News, October 31, 1940, 5.

23 Leo Durocher, 143.

24 Tom Meany, “Crooked Arms Not All on Southpaws.”

25 The Sporting News, August 2, 1945, 10.

26 Fred Fitzsimmons as told to Stanley Frank, “Did the Best Teams Get In The Series?,” The Saturday Evening Post [no date], 112. Player’s Hall of Fame file.

27 Bill Lee, The Baseball Necrology (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland), 131.

Full Name

Frederick Landis Fitzsimmons

Born

July 28, 1901 at Mishawaka, IN (USA)

Died

November 18, 1979 at Yucca Valley, CA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.