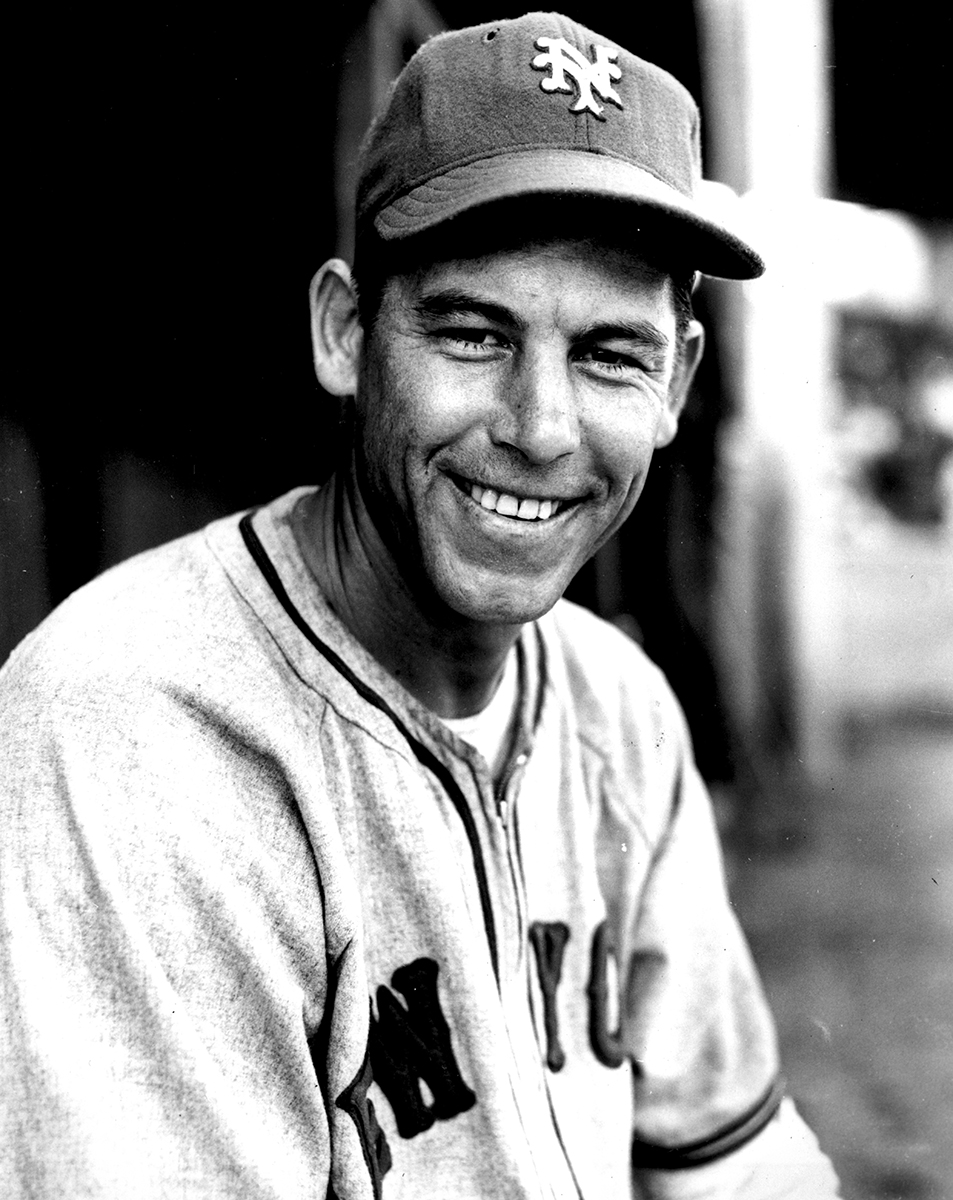

Harry Gumbert

The hallmark of right-handed pitcher Harry Gumbert’s 15-season major league career was versatility. Depending upon club need, he assumed the role of staff ace, rotation regular, spot starter-reliever, or closer. But whatever assignment Gumbert was called upon to fulfill, his persona remained steadfast. Handsome Harry (as he was often called in the press)1 was affable, low-key, and colorless – a quiet family man who was rarely the subject of an amusing story or sports page anecdote. After a brief post-age 40 turn in minor league baseball, Gumbert spent the remainder of his working life as a business executive in the greater Houston area. A look back at the life of this competent and uncontroversial professional follows.

The hallmark of right-handed pitcher Harry Gumbert’s 15-season major league career was versatility. Depending upon club need, he assumed the role of staff ace, rotation regular, spot starter-reliever, or closer. But whatever assignment Gumbert was called upon to fulfill, his persona remained steadfast. Handsome Harry (as he was often called in the press)1 was affable, low-key, and colorless – a quiet family man who was rarely the subject of an amusing story or sports page anecdote. After a brief post-age 40 turn in minor league baseball, Gumbert spent the remainder of his working life as a business executive in the greater Houston area. A look back at the life of this competent and uncontroversial professional follows.

Harry Edwards Gumbert was born on November 5, 1909, in Elizabeth, Pennsylvania, a small town located about 15 miles south of Pittsburgh. He was the fifth of 11 children born to coal mine mechanic Arthur Adam Gumbert (1881-1974) and his wife Elizabeth (née Wilson, 1880-1939).2 The patriarchal side of the family descended from 18th-century German Protestants and settled in the Pittsburgh area prior to 1800,3 while Harry’s mother was of Irish ancestry. The extended Gumbert clan was long active in Pittsburgh-area civic, political, and sporting affairs and included late 19th-century major league pitchers Ad and Billy Gumbert, first cousins two generations removed of our subject.4

When Harry was a boy, the family relocated to the nearby town of Bentleyville, where he attended public school through high school graduation. Although a member of the Bentleyville High baseball team, Gumbert was not a standout.5 Thereafter, he played some local semipro ball, mostly as an outfielder, and pitched for a local steel company team.6 Concentration on pitching accompanied his signing with the Charleroi (Pennsylvania) Governors of the Class C Middle Atlantic League early in the 1930 season. Despite being inexperienced on the mound, Gumbert showed promise, going 13-12 (.520) in 34 games for a fifth-place Charleroi club. Before the season was over, the young hurler was purchased by the Baltimore Orioles of the Class AA International League.7

Although he dropped his only decision in Baltimore livery, Gumbert “made a fine impression in his few starts on the peak … [and] appears to be a fine prospect,” the Baltimore Sun reported.8 In camp the following spring, he continued apace, making a favorable impression on both Orioles manager Fritz Maisel and club general manager George Weiss.9 Gumbert had size (6-feet-2 and 185 pounds), was naturally athletic, and displayed excellent pitching mechanics, propelling a well-spotted fastball, a sharp-breaking curve, and a sinker toward the plate via a smooth overhand delivery. “I liked his looks” from the beginning, manager Maisel informed the press.10 But once the International League season began, Gumbert’s performance became erratic. He turned in first-rate work in relief but was ineffective when given starts.11 Decision-less in 15 appearances but saddled with an unsightly 8.27 ERA, the prospect was optioned to the Class B New York-Pennsylvania League in late July. Pitching for the York (Pennsylvania) White Roses, Gumbert quickly recovered form, going 11-6 (.647) in 23 outings.

History repeated itself in 1932. Gumbert began the season in Baltimore; posted a 7-4 (.647) mark with a high 5.33 ERA for the Orioles and was optioned back to the NY-P League for additional seasoning in mid-August. There, he went 3-3 in 10 games for the Binghamton (New York) Triplets. Once again in camp with Baltimore the following spring, Gumbert seemed to be regressing during exhibition game play. Re-optioned to the New York-Pennsylvania League, by then Class A,12 his 12-15 (.444) mark for the Williamsport (Pennsylvania) Grays included a mid-June 2-0 no-hitter thrown against his former York club.13 But Baltimore brass had grown impatient with Gumbert, and over the winter he was dealt to the Galveston Buccaneers of the Class A Texas League.14

The trade proved a life changer on both the personal and professional level for Harry Gumbert. While in Galveston, he met Rachel House, the teenage waitress who would soon become his wife of almost 60 years, and permanently relocated to the state that he called home for the remainder of his life. Gumbert also got untracked on the mound, going 18-12 (.606) with a tidy 3.09 ERA while leading a pennant-winning (88-64, .579) Galveston club in appearances (42), innings pitched (245), and victories. He then excelled in post-season play, winning three games and saving two others for Galveston in playoff series outings.15 Gumbert’s standout work did not go unnoticed by major league clubs and led to his acquisition by the National League Philadelphia Phillies during the winter.

Gumbert never got a regular season chance with Phillies, being optioned to Baltimore late in 1935 spring training camp.16 Months later, the sale of Gumbert’s contract to Baltimore made the transfer permanent.17 Undiscouraged by his latest demotion, Harry blossomed into the Orioles staff ace, going 19-10 in 46 games. His purchase by the New York Giants in late August and early delivery finally got the 25-year-old Gumbert to the big leagues.18

Harry Gumbert made his major league debut on September 12, 1935, throwing two innings of perfect midgame relief of Giants ace Carl Hubbell in a 5-2 loss to the St. Louis Cardinals. During that brief stint, Gumbert struck out future Hall of Famers Dizzy Dean (an above-average hitter for a pitcher) and Frankie Frisch. In addition to complimenting his fine work, note was made of Harry’s close resemblance – in size, facial features, pitching motion, and reserved demeanor – to Cardinals hurling star Paul (Daffy) Dean.19 Given a start four days later, Gumbert was driven from the mound in the fourth inning of an 8-3 loss to the Chicago Cubs. He soon redeemed himself, however, with a route-going, 11-inning victory over Brooklyn, 3-2. In all, Gumbert made six late-season appearances for New York, going 1-2 (.333) but favorably impressing Giants first baseman-field boss Bill Terry, his 6.08 ERA notwithstanding.

As soon as the season concluded, Harry returned to Galveston, where he and Rachel tied the knot at Central Methodist Church.20 In time, the arrival of Harry, Jr. (born 1939), Melinda (1944), and Rachel (1948) completed the Gumbert family.

Although largely untested, big things by Gumbert were predicted by pressmen covering the Giants’ 1936 spring camp.21 And he did not disappoint, his versatility proving an asset during a pennant-winning (92-62, .597) Giants campaign. Mixing 15 starts into 39 mound appearances, Gumbert posted a sterling 11-3 (.786) record with a 3.90 ERA but exhibited career-long shortcomings in the process. As befitted a pitch-to-contact hurler, neither his ratio of hits allowed (157) to innings pitched (140 2/3) nor that of strikeouts (52) to walks (54) numbers was impressive. These deficiencies were fully exposed during postseason play, as Gumbert was shelled (seven hits, four walks, eight earned runs) in two brief relief outings in the World Series, lost to the New York Yankees in six games.

Little-used in the early going of 1937 – he did not register a decision until May 25 – Gumbert solidified his place on the New York roster with a pedestrian but useful 10-11 (.476) mark that included his first major league shutout, a six-hit, 5-0 whitewash of Chicago on July 25. Meanwhile, the Giants (95-57, .625) captured their second consecutive National League pennant but were again flattened in five World Series games by the Yankees, with Gumbert being drubbed (four earned runs in 1 1/3 innings) in two relief appearances.

With longtime staff stalwarts Carl Hubbell and Hal Schumacher beginning to show signs of wear, Manager Terry moved Gumbert into the Giants rotation for the 1938 season. “It is Terry’s honest conviction that this will be Harry Gumbert’s year,” reported New York sports scribe Tom Meany as the season began.22 Gumbert responded by posting a club-high 15 wins and placing second to Cliff Melton in innings pitched (235 2/3). But the Giants (83-67-2, .553) slid to third place in the NL final standings, as the club’s aging pitching staff faltered.

Almost by default, Gumbert assumed the post of staff ace in 1939, going 18-11 (.621) for a New York club (77-74, .510) that fell to fifth place. Harry again led the Giants staff in victories, as well as starts (34), innings pitched (243 2/3), complete games (14), and shutouts (2).23 Accompanying these numbers, however, was a high 4.32 ERA and Gumbert’s customarily lackluster hits allowed total (257) and ratio of strikeouts (81) to walks (81). The Giants’ slide continued the following year, as no rotation regular posted a winning record for the sixth-place (72-80, .474) finisher. Gumbert’s 12-14 (.462) mark typified staff mediocrity, but he again paced club hurlers in starts (30), innings pitched (237), and complete games (14).24

Throughout his stay with a ballclub situated in the sports and media capital of the world, Gumbert generated very little ink. Invariably cordial, well-spoken, and liked by teammates, club management, and writers covering the Giants, Harry was simply poor copy, a quiet family man not given to off-field escapades or piquant quotations. The only discovery unearthed by the press was that Gumbert had a fondness for whittling and wood carving during his free time.25

Gumbert started the 1941 season slowly, registering only one victory in five starts. The Giants then unloaded him, sending Gumbert and $20,000 to the St. Louis Cardinals in exchange for right-hander Fiddler Bill McGee, just coming off a 16-win season.26 The deal proved a lopsided one – in St. Louis’ favor. While McGee struggled (2-9, .182) in New York, Gumbert proved an excellent fit with the pitching-rich Cardinals. Alternating between starting and relief work, he went 11-5 (.688) with an excellent 2.74 ERA in 144 1/3 innings pitched for St. Louis, a strong (97-56-2, .634) second-place finisher in NL final standings.

Gumbert repeated his excellent spot starter-reliever work the following season, posting a 9-5 (.643) record in 38 games for a pennant-winning (106-48-2, .688) Cardinals club. He then made brief but helpful relief appearances during the Redbirds’ five-game World Series triumph over the New York Yankees. Harry and the Cardinals encored in 1943. Used mostly as a spot starter for another NL pennant winner, Gumbert went 10-5 (.667) with a 2.84 ERA in a season highlighted by a pair of consecutive shutouts thrown in early July.27 Late that season, however, Gumbert’s pitching wing went dead – the only time in his long career that he suffered arm trouble.28 A six-hit complete-game victory over the Giants near season’s end suggested that Gumbert had recovered. But he saw no action in the Fall Classic as the Yankees returned the previous year’s favor, downing the Cards in five games.

Gumbert resumed his familiar spot starter-reliever role for St. Louis the following year. But after posting a complete-game 4-1 victory over Cincinnati in mid-June, he was unexpectedly sold to the Cincinnati Reds.29 According to St. Louis club owner Sam Breadon, the team was not drawing well and he needed the $25,000 received from the sale. “This is an expensive ball club,” Breadon explained. “We have a heavy pay-roll. We must get the money some place!”30 Promptly inserted into the rotation, Gumbert won his Reds debut, setting down Chicago on five hits, 5-2. He thereafter provided the club with reliable work, going 10-8 with a 3.30 ERA in 24 appearances for Cincinnati.

As a 34-year-old married man with two young children, Gumbert was not a probable target for conscription into World War II. Despite that, he enlisted in the US Army in March 1945 and missed the ensuing major league baseball season. Private Gumbert spent his military time stateside and was honorably discharged in November.31 The following spring, he rejoined the Reds.

During the 1946 campaign, Gumbert began the transition to full-time relief pitcher. “Handsome Harry” moved “right into the king row among relief pitchers” reported Cincinnati sportswriter Tom Swope after a trio of effective relief outings in late May.32 But perhaps Gumbert’s most noteworthy achievement that season was the four innings of scoreless relief work that he contributed to an epic 19-inning 0-0 draw against Brooklyn in mid-September.33 At season’s end, his 6-8 (.429) record was about on par with that posted overall by the sixth-place (67-87-2, .435) Reds. Used exclusively in relief the following year, Gumbert improved to 10-10 (.500) in 46 outings for another mediocre (73-81, .474) edition of the Cincinnati Reds. But a Gumbert pitching tip to road roommate Ewell Blackwell helped transform the erratic sidearmer into the National League’s premier hurler in 1947.34

Had a Fireman of the Year award existed in 1948, Gumbert would likely have received it. Moving into the role of closer, he posted a 10-8 (.566) record for another second-division Cincinnati club while leading National League hurlers in appearances (61), games finished (46), and saves (17, calculated retroactively). Relief was considered a thankless job at the time, but Harry did not mind being used exclusively out of the pen. “Somebody’s got to do it. Might as well be me,” he said, philosophically.35

After a brief spring holdout, Gumbert signed for the 1949 season for the same $15,000 salary that he had received the previous year.36 He could not flash his previous form, however, once the season commenced: a bloated 5.53 ERA in 29 appearances revealed more than his winning (4-3, .571) record. Placed on waivers in late July, Gumbert signed with the Pittsburgh Pirates.37 Retired Pirates legend Pie Traynor – by then host of a sports radio show in Pittsburgh – had misgivings about the acquisition, opining that Gumbert “never had much of a fastball. His sinker is tough to hit, though, and he will fool a lot of batters with that little slow curve ball over the outside corner.”38 But Harry was delighted, “I was really glad to get with the Pirates,” he said. “Naturally this is a favorable place for me. As you know, I started my career in [nearby] Charleroi.”39

Unhappily, a return to youthful haunts did not revitalize Gumbert’s pitching line. He was as ineffective in Pittsburgh (1-4, .200, with a 5.86 ERA in 16 relief appearances) as he had been earlier in Cincinnati. Nevertheless, he managed to top National League relievers in games finished (33) and was re-signed by the Pirates for the 1950 season. Harry made the Opening Day roster but was ineffective in his lone appearance – three hits, two walks, three runs allowed in 1 2/3 innings against Cincinnati on April 29. With roster cutdown day looming, Gumbert was unconditionally released the following week.40 His major league career was over.

Appearing in over 500 games over 15 major league seasons, Gumbert had compiled a creditable 143-113 (.559) record, with 46 saves. His total of base hits allowed (2,186) slightly exceeded his innings pitched (2,156) and he walked more batters (721) than he fanned (709). Yet his 3.68 ERA was respectable – a shade better than the NL average over his career. And he had been an exceptional fielder, leading NL hurlers in putouts (once), assists (three times), and range factor (five times). He was also a positive, if quiet, clubhouse presence.

From the beginning to the end of his professional career, Gumbert benefited from widespread misapprehension of his true age.41 By then 40, he was believed to be three or four years younger and various minor league clubs sought his services. Within days of his release by Pittsburgh, Gumbert signed with the Sacramento Solons of the Class AAA Pacific Coast League, where local news outlets reported his age as 3642 or 37.43 But ageless Harry proved no better than the last-place (81-119, .405) club that he joined, going 7-12 (.368) with an inflated 5.35 ERA.

Over the winter, Gumbert campaigned for a minor league managing job.44 To accommodate him (and to partially recoup the $5,000 signing bonus given Gumbert the previous spring), Sacramento sold his contract to the Galveston White Caps of the Class B Gulf Coast League.45 There, he assumed the roles of rotation regular (11-9 in 32 games), field leader (71-83, fifth place), and beginning in mid-July, club general manager.46 He retired from pitching and managing the following season to focus on his duties as new White Caps club president/general manager.47 But late in the 1952 campaign, he retook the managerial reins, as well.48 Galveston finished fourth but lost in the opening round of the GCL playoffs.

In February 1953, a salary dispute – club ownership declined to renew Gumbert’s contract at the $7,500 figure that he had been paid the previous season – led to his departure as club president/GM.49 Apart from appearing in the occasional old-timers game, Harry’s association with professional baseball had come to its end.50

Since the late 1940s, Gumbert had worked as an insurance agent during the offseason; that became his full-time occupation. During the 1950s, he joined the sales force at American Armature Works, Inc., an industrial motors manufacturer and repair business located in Houston, eventually retiring as a company vice-president.51 He was also active in local retired ballplayer associations.

In 1969, Gumbert and wife Rachel sold their home in Houston and relocated to Wimberley, a small town in central Texas.52 There, the Gumberts operated an antique store and a furniture refinishing business.53 In his leisure time, Harry enjoyed deer hunting, fishing, and the arrival of grandchildren. He was also a founding member and first president of the Wimberley Masonic Lodge.54

Stricken with cancer late in life, Harry Edwards Gumbert died in a Wimberley hospital on January 4, 1995. He was 85. Following funeral services conducted at the Chapel in the Hills Church, the deceased was interred at Wimberley Cemetery. Survivors included his widow, three children, three granddaughters, and siblings Mildred Dennick, Lucille Confer, and Eugene and Ralph Gumbert.

Acknowledgments

This biography was reviewed by Darren Gibson and Rory Costello and fact-checked by Ray Danner.

Sources

Sources for the biographical info imparted above include the Harry Gumbert file maintained at the Giamatti Research Center, National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum, Cooperstown, New York; US Census data and other government records accessed via Ancestry.com; and certain of the newspaper articles cited in the endnotes. Unless otherwise specified, stats have been taken from Baseball-Reference and The Encyclopedia of Minor League Baseball, Lloyd Johnson & Miles Wolff, eds. (Durham, North Carolina: Baseball America, Inc., 3d ed. 2007).

Photo credit: Harry Gumbert, SABR-Rucker Archive.

Notes

1 Tall with jet black hair and blue eyes, Handsome Harry was a fine-looking man. The Gunboat nickname today more frequently associated with Gumbert was an alliterative but meaningless sportswriter contrivance that only appeared on occasion in the newsprint of his playing days.

2 The other Gumbert children were Charles (born 1902), Florence (1903), Mary (1905), Mildred (1907), Alice (1911), George (1914), Eugene (1916), Lucille (1919), James (1922), and Ralph (1927).

3 The Gumbert family tree emanates from Christian Gumbert (originally Gumber, 1740-1835), a Revolutionary War patriot who eventually settled in Allegheny County, Pennsylvania.

4 During Harry’s lifetime and to this day, he is sometimes misidentified as the grand-nephew of the Gumbert brothers. Their actual familiar relationship is the somewhat more distant first cousins, twice removed, and derives from mutual forebear George Gumbert, Sr. (1794-1871), the grandfather of Ad and Billy and the great-great-grandfather of Harry Gumbert.

5 Harry Gumbert, “Gumbert Had Trying Time Pursuing Ball Ambitions but Finally Made Good,” Baltimore Evening Sun, June 16, 1932: 32, contradicting reports that Gumbert had not played high school baseball.

6 Same as above. See also, “Minors Coming Up to Majors: Harry Gumbert,” The Sporting News, September 26, 1935: 2. According to daughter Melinda, Harry’s foray into semipro baseball cost him a track scholarship to Washington and Lee University. See Melinda Gumbert, “Rachel House and Harry Gumbert,” unidentified manuscript contained in the Harry Gumbert file at the Giamatti Research Center.

7 “Orioles Buy Gumbert from Charleroi Club,” Baltimore Sun, September 3, 1930: 15. For $2,000, the Orioles retained the rights to Gumbert through May 15 of the following season before having to decide whether to keep him on the roster or return him to Charleroi.

8 “Orioles Scatter Afar to Spend Winter,” Baltimore Sun, September 23, 1930: 15.

9 Per “Birds Sell Pitcher Walsh to ‘Frisco Club,” Baltimore Evening Sun, March 13, 1931: 41.

10 Same as above.

11 See “Fans Stumped by Gumbert’s Failure as Starting Hurler,” Baltimore Evening Sun, May 27, 1931: 33.

12 Per “Orioles Get Twirler Picknell from Phils,” Baltimore Sun, April 27, 1933: 29.

13 “Harry Gumbert Pitches No-Hit, No-Run Game,” Baltimore Evening Sun, June 14, 1933: 24. Only an infield error stood between Gumbert and a perfect game. He won, 2-0.

14 As reported in “Yank Boss Plans to Use Harry Smythe to Check Southpaw Hitters,” Baltimore Evening Sun, December 21, 1933: 35. George Weiss, by then general manager of the Newark Bears, remained a Gumbert admirer but his offer of four players in exchange for the still-young pitcher was rejected by Galveston.

15 Holly Hollingsworth, “Sports of Meter,” Longview (Texas) News-Journal, September 26, 1934: 6. Galveston defeated Dallas and San Antonio in Texas League playoff matches but subsequently dropped the inter-league Dixie Series to Southern Association champion New Orleans in six games.

16 As reported in “Orioles Get Gumbert,” Buffalo Evening News, April 22, 1935: 8; “Orioles Obtain Harry Gumbert in Option Deal,” Baltimore Evening Sun, April 20, 1935: 1; and elsewhere.

17 See Randall Cassell, “Bucks Sell Outfielder Abernathy to Phils,” Baltimore Evening Sun, July 12, 1935: 31. Baltimore sent outfielder Woody Abernathy to Philadelphia in exchange for Gumbert’s contract and an undisclosed amount of cash.

18 “Giants Purchase Harry Gumbert to Bolster Chances,” (Jersey City) Jersey Journal, August 31, 1935: 10; “Giants Buy Orioles’ Kid Star,” New York Daily News, August 31, 1935: 25. Gumbert was originally slated for delivery at season’s end, but with the Orioles out of the IL pennant chase, the pitcher’s transfer was expedited. See “Gumbert Is Now a New York Giant,” Baltimore Evening Sun, September 9, 1935: 22.

19 See e.g., “Gumbert Keeps Giants’ Hopes Alive, Brooklyn Times Union, September 13, 1935: 11; “Warm Praise for Former [Oriole],” Baltimore Evening Sun, September 13, 1935: 4, citing the appraisals of New York sportswriters Rud Rennie (New York Herald) and John Drebinger (New York Times).

20 Per State of Texas marriage records, accessed via Ancestry.com. Harry Edwards Gumbert and Rachel Hume House were joined in matrimony on October 28, 1935.

21 See e.g., “Broaca Sets Goal at 20 Victories; Terry May Have Winner in Gumbert,” Brooklyn Times Union, March 28, 1936: 11, which also contains the first discovered newsprint mention of the Gunboat nickname: “Dark-haired and serious-faced, Gumbert resembles Paul (Daffy) Dean. Like Daffy, he is not particularly colorful. Were he the younger brother of a more illustrious pitcher, however, they’d probably be calling him Gunboat Gumbert.”

22 Tom Meany, “Terry’s Flag Problem Is Jig-Saw Hill Puzzle,” The Sporting News, April 28, 1938: 3.

23 Cliff Melton also registered two shutouts for the 1939 Giants.

24 Hal Schumacher tied Gumbert for club lead with 30 starts.

25 As related in “Harry Gumbert Is Good with a Knife,” New York Sun, April 13, 1939. See also, an unidentified circa 1943 press clipping contained in the Gumbert file at the Giamatti Research Center.

26 As reported in Joe Trimble, “Giants Get M’Gee for Gumbert,” New York Daily News, May 15, 1941: 54; “M’Gee Is Traded by Cards for Gumbert of Giants,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, May 14, 1941: 13; and elsewhere.

27 On July 6, Gumbert shut out the Philadelphia Phillies on three hits, winning 4-0. Five days later, he scattered six hits in a 3-0 whitewash of the Boston Braves.

28 See “Wray’s Column: Harry Gumbert’s Arm Still ‘Freezes’ after Three or Four Innings,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, September 3, 1943: 24.

29 As reported in “Redlegs Buy Harry Gumbert in Straight Cash Transaction,” Cincinnati Enquirer, June 16, 1944: 12; Tom Swope, “Reds Buy Gumbert after 1-0 Defeat,” Cincinnati Post, June 16, 1944; and elsewhere.

30 “Breadon Explains Sale of Gumbert,” St. Louis Star-Times, June 16, 1944: 22.

31 Per Gumbert military records accessed via Ancestry.com.

32 Tom Swope, “Gumbert Moves to Top Among Relief Hurlers,” Cincinnati Post, May 30, 1946: 7.

33 The Ebbets Field game was called by darkness after four hours, 40 minutes and remains the longest scoreless game in major league history as of the end of the 2023 season.

34 A nine-game winner the previous season, Blackwell went 22-8 (.733) and led NL pitchers in victories and strikeouts (193). Blackwell credited his dramatic improvement to advice on how to pitch left-handed batters imparted by Gumbert. See Tom Swope, “Gumbert’s Tip Helps Blackie Halt Hitters,” Cincinnati Post, June 14, 1947: 8.

35 Jimmy Miner, “‘Fireman’ Gumbert Is One of League’s Busiest Pitchers,” Cincinnati Post, August 25, 1948: 19.

36 As reported in “Gumbert Ends Siege; Raffensberger Ready,” Cincinnati Enquirer, March 13, 1949: 53; “Harry Gumbert, Lone Cincy Holdout, Signs,” Lincoln (Nebraska) Sunday Journal, May 13, 1949: 18; and elsewhere.

37 Per “Reds Send Gumbert to Bucs on Waivers,” Cincinnati Post, July 27, 1949: 1; “Gumbert Added to Pirate Staff,” Pittsburgh Press, July 27, 1949: 25. The waiver price tag was reportedly $10,000. See Harry Keck, “Sports,” Pittsburgh Sun-Telegraph, July 28, 1949: 28.

38 Roy McHugh, “Sports Stew Served Hot,” Pittsburgh Press, July 29, 1949: 21.

39 Chilly Doyle, “Pirate Chilly Sauce,” Pittsburgh Sun-Telegraph, July 29, 1949: 17.

40 See “Pirates Drop Two Pitchers,” Pittsburgh Sun-Telegraph, May 7, 1950: 35; “Pirates Drop Harry Gumbert,” Tampa Tribune, May 7, 1950: 60.

41 Gumbert’s TSN card originally listed his date of birth as November 5, 1912, and he was believed to be 22 during his first spring camp with the New York Giants. See “Broaca Sets Goal at 20 Victories,” above. Gumbert was actually three years older.

42 See Tom Kane, “Solons Sign Former Ace National League Hurler Harry Gumbert,” Sacramento Bee, May 11, 1950: 54.

43 “Harry Gumbert’s Record,” Sacramento Union, May 12, 1950: 8.

44 As reported in “Gumbert May Quit Solons to Manage,” Sacramento Union, December 17, 1950: 18.

45 Per “Gumbert Going Back to the Isle,” Houston Post, January 25, 1951: 36; “Solons Sell Harry Gumbert to Galveston as Manager,” Sacramento Union, January 24, 1951: 6.

46 Gumbert’s assumption of the post as Galveston general manager was reported in “Gumbert Filling Two Baseball Jobs,” Dallas Morning News, July 14, 1951: 4; “Harry Gumbert Gets Additional Job,” Wichita Falls (Texas) Times, July 13, 1951: 11; and elsewhere.

47 Wayne Spraggins, “Gumbert Promises Better Club on Isle,” Houston Post, January 13, 1952: 43.

48 See “Goletz Released, Gumbert New Galveston Pilot,” Houston Post, September 3, 1952: 21; “Goletz Out as Boss of Galveston Club,” San Antonio Light, September 3, 1952: 17. Former Chicago White Sox pitcher-outfielder Stan Goletz began the 1952 season as Galveston manager.

49 As reported in “Salary Demands Oust Gumbert at Galveston,” Fort Worth Sun-Telegram, February 2, 1953: 10; “Harry Gumbert Out of Galveston Job,” Odessa (Texas) American, February 1, 1953: 10; and elsewhere.

50 In 1958, Gumbert was reportedly a candidate for the managerial post with the Dallas Rangers of the Class AA Texas League. See “Schepps Dallas General Manager,” Corsicana (Texas) Daily Sun, February 8, 1958: 7; “Schepps Seeks Tieup for Dallas,” Fort Worth Star-Telegram, February 8, 1958: 14. He did not get the job.

51 Per the player questionnaire personally completed by Harry Gumbert contained in his file at the GRC.

52 According to Bill Roberts, “The Town Crier,” Houston Post, September 17, 1969: 14.

53 Melinda Gumbert, above.

54 Per the Gumbert obituaries published in the Austin American-Statesman and Wimberley (Texas) View, January 6, 1995.

Full Name

Harry Edwards Gumbert

Born

November 5, 1909 at Elizabeth, PA (USA)

Died

January 4, 1995 at Wimberley, TX (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.