Ewell Blackwell

Fear. Ballplayers don’t like to talk about it. Rarely is a pitcher so fearsome that he can’t be ignored. Walter Johnson was one. Bob Feller. Randy Johnson.

Fear. Ballplayers don’t like to talk about it. Rarely is a pitcher so fearsome that he can’t be ignored. Walter Johnson was one. Bob Feller. Randy Johnson.

Ewell Blackwell was one. Batters weren’t called cowards when they admitted they were afraid of him.

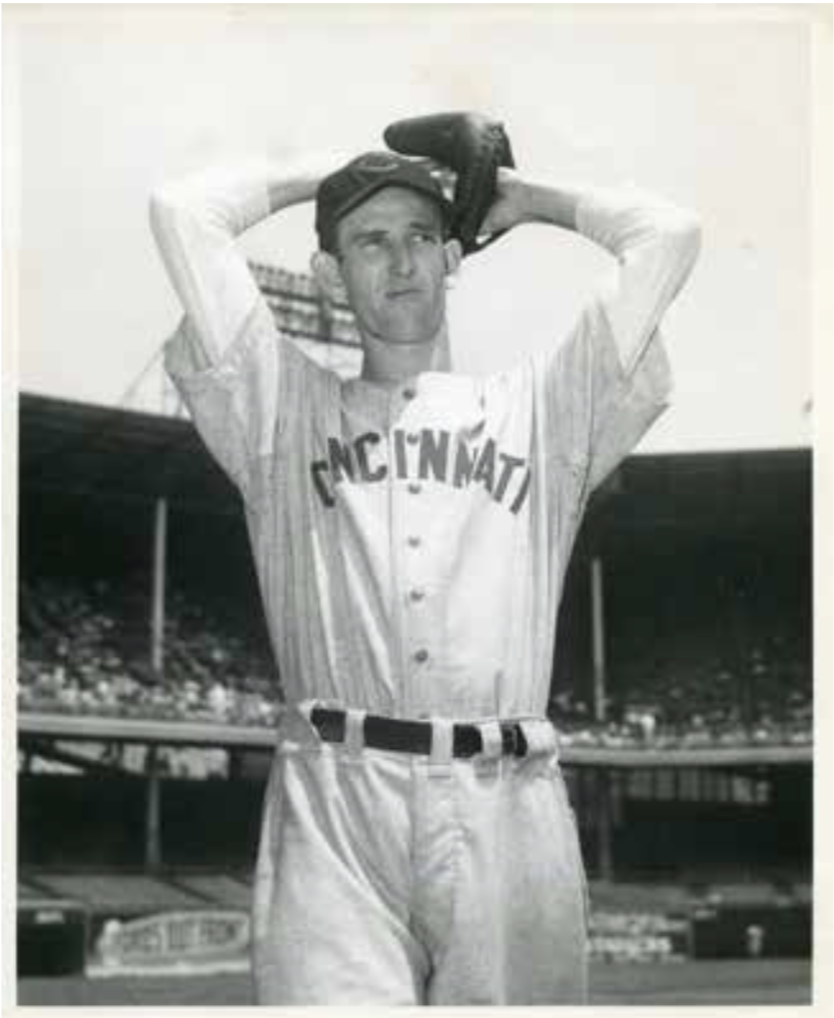

Ewell Blackwell was “The Whip,” a long, lanky sidearming right-hander who threw a heavy sinking fastball that just might bore a hole in you if it hit you. And he didn’t mind hitting you; he said, “I was a mean pitcher.”1

Blackwell’s short career foundered on Murphy’s Law: Everything that could go wrong did. For a single shining season, 1947, he was the most dominant pitcher on the planet, but he pitched for one losing Cincinnati team after another while fighting poor health and chronic shoulder pain.

The sportswriter Red Smith wrote that Blackwell was “built like a slouchy flyrod, being composed largely of arms and neck and ears.” Another writer, Joe Williams, thought his delivery looked like “a Picasso impression of an octopus in labor.”2

Hitters thought he was trouble. Some of the best—Ted Williams, Joe DiMaggio, Ralph Kiner, Jackie Robinson, Roy Campanella—moaned about facing him. Stan Musial said, “I don’t see how Blackwell ever loses a game.”3

Ewell Blackwell was born in Fresno, California, on October 23, 1922, to Flugin Ewell and Edna Blackwell. The family, which included two daughters, moved to San Dimas, where Flugin worked as a cleaner and dyer and later went into real estate sales. Flugin, a sandlot third baseman, started his son at the same position. Ewell was a scrawny boy, standing only five-foot-five at age 13. After he shot up to six-three he preferred basketball to baseball.

Bonita High School’s coach, noticing that Ewell threw harder than anyone else on the team, made him a pitcher. Dad built a wooden box the size of the strike zone in the backyard, and the boy threw baseballs and tennis balls at the target to develop control. He won a scholarship to LaVerne Teachers College in Los Angeles County, but stayed only one semester. While working as a riveter at the Vultee Aircraft plant in 1941, he pitched for the company team. Major league scouts soon began paying attention.

When the scouts came calling, Ewell and his father showed more interest in a quick path to the majors than in a big bonus. They demanded an invitation to a big league spring training camp. The Cardinals’ Branch Rickey and the Dodgers’ Larry MacPhail vetoed that, as did several other teams. Cincinnati scout Pat Patterson gave the Blackwells what they wanted, and promised to assign the teenager to the Reds’ Class C farm club in Ogden, Utah, his mother’s hometown. Ewell signed for a $750 bonus, plus an additional $250 if he stuck until mid-season.

When Blackwell arrived at the Reds’ spring camp in Tampa, Florida, in 1942, manager Bill McKechnie watched him throw and told general manager Warren Giles, “Boss, you’ve got a natural.” Speaking to writers later in the spring, McKechnie predicted that the gawky 19-year-old would be “one of the all-time greats.”4 Forget Ogden; the Reds put him on the major league roster.

He pitched just twice for Cincinnati before he was sent down to Syracuse. He was an immediate star at the top minor league level in his first professional season, posting a 2.02 ERA and a 15-10 record, including four shutouts. He pitched three more shutouts, plus three innings of scoreless relief, in the International League playoffs, but came down with pneumonia and missed the Junior World Series, which Syracuse lost.

The Reds had won back-to-back pennants in 1939 and 1940 before falling to a .500 record in 1942. Young Blackie looked like the man to lead them back to the top. However, as the saying went, “There’s a war on.” Blackwell was drafted into the army in January 1943. He told his commanders about his experience working on military aircraft at Vultee, so, naturally, they made him a cook. “I’d never boiled an egg in my life and could hardly make a glass of lemonade,” he said.5

Blackwell’s 71st Infantry Division arrived in Germany in January 1945. The war was almost over, but deadly combat continued. “I never got shot at, but I got scared plenty when those eighty-eights (German artillery shells) started going off over my head,” he remembered.6 He was with General George S. Patton’s Third Army when it linked up with Soviet Red Army in Austria. After Germany surrendered in May, mess sergeant Blackwell served his unit a banquet topped off with apple pies. He downed one of the pies by himself.

When the fighting ended, the army found a more fitting use for Blackwell’s talents: pitching for the division baseball team. His teammates included major leaguers Harry Walker, Johnny Wyrostek, and Ken Heintzelman. In September 1945 he won the first game of the European championship series in front of more than 50,000 soldiers at the huge Nuremberg stadium where Adolf Hitler had harangued the Nazi faithful. He was the losing pitcher in the decisive fifth game against the Oise Base all-stars.

As the Reds opened spring training in 1946, writer Red Smith listened to manager McKechnie and GM Giles drooling over a rookie right-hander named Blackwell. When Smith asked where he could see this phenom, McKechnie replied glumly, “Germany.”7 Blackwell pitched a no-hitter in an army game in Nuremberg shortly before he was shipped home. Arriving in Tampa three weeks late, he worried about whether he was ready to face big league hitters. He had played against Ted Williams in a high school tournament; after an exhibition game he asked Williams how his stuff looked. Williams warned him that he was tipping his changeup. The Reds’ veteran ace, Bucky Walters, spent hours talking to him about the strategy of pitching.

The 23-year-old beanpole had grown to his full height of 6’5 ½” and weighed less than 190. In his rookie season he was everything McKechnie had hoped for: an overpowering pitcher with his fastball and a curve that he threw hard and soft. His 2.45 ERA was fourth best in the NL, but his record was just 9-13 for a sixth-place team that finished last in runs scored. Five of his victories were shutouts, the most in the league. His most eye-popping number: one home run allowed in 194 1/3 innings. He pitched in the first of six consecutive All-Star Games, the first National Leaguer to do that.

Before he went overseas, Blackwell had married a woman he had met in Syracuse, Arlene Knowlton. He returned to her hometown after the season with an offer to play for the local National Basketball League team. The Reds wouldn’t allow it, but paid him a $3,000 bonus to compensate for the lost income. His wartime marriage soon broke up.

Blackwell started slowly in 1947. His ERA was above 5.00 before he beat the Cubs on May 10. Over the next two months he won 16 straight decisions, a record for a NL right-hander. He completed 16 of 17 starts (one was a no-decision), including five shutouts. He limited opposing batters to a .503 on-base plus slugging percentage and compiled a 1.34 ERA during the streak. He was not just unbeatable, but practically unhittable.

On June 18 he started against the Boston Braves, who had scored 36 runs in their previous three games. He held them hitless for 8 2/3 innings, then faced left fielder Bama Rowell with two out in the ninth. He recalled retiring Rowell for the last out in his army no-hitter. Can’t happen again, he thought. It did. Blackwell struck out Rowell to finish his gem.

On June 18 he started against the Boston Braves, who had scored 36 runs in their previous three games. He held them hitless for 8 2/3 innings, then faced left fielder Bama Rowell with two out in the ninth. He recalled retiring Rowell for the last out in his army no-hitter. Can’t happen again, he thought. It did. Blackwell struck out Rowell to finish his gem.

After the game photographers had trouble finding a teammate to give him the ritual hug. He had refused to wash his sweatshirt since the winning streak began five weeks earlier. His roommate, Grady Hatton, said, “Frankly, it stinks.”8

In a postgame radio interview the cocky Blackwell predicted he would pitch another no-hitter his next time out. Four days later he stopped Brooklyn without a hit through 8 1/3. His teammate Johnny Vander Meer, the only man to pitch consecutive no-hitters, was on the top step of the dugout, wanting to be the first to shake his hand. Then Eddie Stanky smacked a hard grounder back at Blackwell and it skipped between his legs to roll dead on the grass in center field. A hit all the way. “I must have replayed that moment a thousand times,” he said years later. “Should I have gotten down quicker and stopped the ball? It seems as though I should have, but probably not. But it was awful tough to be so close and lose it that way.”9 He retired Al Gionfriddo on a fly ball for the second out. Still raging, he greeted the next batter, Jackie Robinson, “with an explosion of racist insults,” according to Robinson’s biographer, Arnold Rampersad.10 Robinson answered with a single, the Dodgers’ second hit, before Blackwell retired Carl Furillo for the last out.

Blackwell was chosen to start the All-Star Game at Chicago’s Wrigley Field. He struck out the AL leadoff batter, George Kell, and fanned three more future Hall of Famers—Ted Williams, Lou Boudreau, and Joe Gordon—in three shutout innings. He got Williams looking at a changeup that wasn’t tipped off. (Williams always insisted it was low.) Boudreau said, “Right now Blackwell is as good a pitcher as Bobby Feller.”11

The end of the winning streak was a heartbreaker. On July 30 Blackwell carried a 4-3 lead into the ninth against the Giants. He tried to brush back Willard Marshall, but left the ball over the plate and Marshall smashed a homer to tie the score. In the tenth a Giants runner stood at second with two out. Blackwell had two strikes on Buddy Kerr when he threw a curve that he thought “cut the middle of the plate, belt-high.” The umpire called it a ball. On the next pitch Kerr rapped an RBI single over shortstop to beat him.12 Let’s not try to imagine what his sweatshirt smelled like by then.

He lost another extra-inning game nine days later in Chicago on Bill Nicholson’s eleventh-inning homer. Blackwell’s parents had come east to see him pitch for the first time, and his mother sat in the stands crying after it was over.

After his twentieth victory on August 27, he set a goal of 25. But he twisted a knee when the Dodgers’ Pete Reiser slid into him on a play at the plate and missed at least two starts. He finished the season 22-8, racking up almost one-third of the wins by the fifth-place Reds.

He led the National League in victories, complete games, and strikeouts. His 2.47 ERA was second in the league. He finished second in the MVP voting behind the Braves’ Bob Elliott. Two other stats best illustrate his dominance: He was the only major league pitcher to strike out twice as many as he walked and his 6.4 strikeouts per nine innings was nearly double the NL average. No surprise that a poll of players named him the league’s toughest pitcher.13

Blackwell’s sidewheeling delivery terrified right-handed hitters. Ralph Kiner said, “Your legs shook when you tried to dig in on him.” An anonymous Dodger confessed, “Mornings of the days he pitched against us I just couldn’t keep food down.”14 Left-handers had trouble picking up the ball out of his jerky motion. “He is the only pitcher I know who hides the ball four times and shows the ball to you four times,” a fellow pitcher, Hal Newhouser, said. “That is, you see it, the ball disappears, and then you see it again.”15 Several batters said he looked like a man falling out of a tree, with one foot in the air and arms flailing.

At 25 Blackwell was charting a course to the Hall of Fame. He ran aground in Columbia, South Carolina, during an exhibition game on a chilly, damp day in the spring of 1948, when he felt a stabbing pain in his shoulder. In the macho world of 1940s baseball, a real man pitched through pain. He gutted it out until May 7, when he left a game against the Braves after giving up two home runs and six walks. “I’d wind up and begin to deliver, and halfway through my delivery it would feel like somebody was sinking his teeth into my shoulder,” he said. He couldn’t raise his arm above his head.16 He sat out for three weeks, then returned to a more-or-less regular rotation. He completed only four of 20 starts as his ERA shot up to 4.54.

It got worse. In January 1949 surgeons removed Blackwell’s infected right kidney. One doctor predicted his career was over, because the surgery cut through the heavy muscles of his right side and back, muscles that must stand up to the violent torque of a pitching motion. He reported to spring training at 170 pounds, 20 pounds below his usual playing weight.

Blackwell didn’t make his first appearance of 1949 until May 1, and that was too soon. He labored in relief for two months, tried three starts, and went back to the bullpen, where he was knocked around some more. It wasn’t until September that he began to look like the dreaded Blackie, striking out 15 in 18 relief innings and posting a 2.50 ERA.

For the next two years Blackwell regained a semblance of his peak form. In 1950 he led the league with 6.5 strikeouts and only seven hits allowed per nine innings. He also led in wild pitches and hit batters, so nobody was digging in. One day he got two strikes on Bob Dillinger, a right-handed hitter with a .306 lifetime average who had just come over to Pittsburgh from the American League. Dillinger turned to umpire Al Barlick and said, “Al, you can call me out any time you want. I don’t want any more of this guy.”17 Blackwell finished with a bang, giving up only two earned runs in his last 35 innings and shrinking his ERA to 2.97, second best in the circuit. He posted a 17-15 record for the sixth-place Reds, even though his season ended early because of an appendectomy. He delivered more of the same in 1951: 16-15, 3.44, although his strikeout rate fell to 4.6. At 28 he appeared to have salvaged his career.

It was a false spring. The 1952 season was a disaster. Blackwell’s record stood at 1-5 when he faced the Dodgers on May 21 at Ebbets Field. After he retired the leadoff hitter, Brooklyn attacked with a walk, home run, double, walk, and single for four runs before Blackwell was relieved. He showered and went back to the team’s hotel. Walking into the bar, he looked up at the TV and saw the Dodgers were still batting in the bottom of the first. A few minutes later the pitcher who had replaced him, Bud Byerly, sat down beside him. Blackwell asked, “Don’t you want to know what the score is?” Byerly replied, “Frankly, no.” The Dodgers had put up 15 runs in the first inning on the way to a 19-1 rout. “Don’t feel so bad,” Blackwell said. “At least they can’t blame it all on us.”18

Blackwell insisted his arm was fine, but his performance was not. He was 3-12 with a 5.38 ERA in August when the Reds traded him to the New York Yankees for pitcher Johnny Schmitz, three minor leaguers, and a reported $35,000. The deal outraged the other American League teams, who were trying to hold off the Yankees’ drive for their fourth straight pennant. The Yankees had made a specialty of picking up National League veterans in late-season waiver transactions; Johnny Mize and Johnny Sain had preceded Blackwell. Under the rules, a player could pass through waivers in the NL, and then any AL team could work out a trade for him without going through the waiver process, where the last-place club had first refusal. During the off-season the majors changed the rule to require waivers in both leagues for any deal after July 15.

In Blackwell’s eight seasons with Cincinnati, the club never had a winning record. Now he wore an extra-long suit of pinstripes in the World Series. He didn’t expect to see much action behind New York’s Big Three of Allie Reynolds, Vic Raschi, and Ed Lopat. But after the Yankees and Dodgers split the first four games, Casey Stengel named Blackwell the surprise Game 5 starter. Stengel didn’t want to send Raschi out on two days’ rest.

Blackwell took the mound in Yankee Stadium before more than 70,000 fans. The Dodgers, of course, knew him well. Brooklyn’s leadoff batter, Billy Cox, said hello with a single, but Blackwell got out of the first inning without allowing a run. There was no storybook ending. In the second a walk and two singles gave the Dodgers a 1-0 lead. They added three more in the fifth, when Duke Snider homered, and Blackwell left for a pinch hitter. The Yankees battled back to take the lead, and take Blackwell off the hook, before Snider won the game for Brooklyn with an RBI double in the eleventh.

His shoulder flared up again the next year and he left the Yankees in mid-season. The club invited him to spring training in 1954, without a contract, but he couldn’t pitch. Announcing his retirement at 31, he said, “I have a pain all the way up from my elbow to my shoulder.”19

He changed his mind after a couple of months’ rest and joined the Licey Tigres in the Dominican Republic’s league. He could still be effective; on May 22, he won a 1-0 decision over Johnny Wright of Águilas Cibaeñas when pinch-hitter Diómedes Olivo broke up Wright’s no-hitter in the ninth. By September Blackwell had gone home with a sore arm.

The Yankees gave him another chance in 1955. He showed enough in spring training that they were able to sell him for a reported $50,000, plus pitcher Tom Gorman and first baseman Dick Kryhoski, in the first of their many deals with the newly transplanted Kansas City A’s.

Blackwell relieved in the first major league game in Kansas City and pitched the final three scoreless innings to earn a save in a 6-2 victory over Detroit. He was hit hard in his next outing and was released on April 30. Still not ready to give up, he hooked on in the Pacific Coast League—first with San Francisco and then with Seattle, where he helped pitch the Rainiers to the pennant in his final professional season.

Blackwell had settled in Tampa, the Reds’ spring training home, with his second wife, Dorothy Davenport, and their daughters, Linda and Debbie. He owned a liquor store for a while, then joined a large distillery company as a salesman. He was promoted to state manager in South Carolina and moved his family to Columbia. He played in old-timers’ games and was a regular at the springtime ballplayers’ golf tournament in Florida, which he helped organize. He was elected to the Reds hall of fame in 1960.

In retirement Blackie and Dottie moved to the mountains of North Carolina. He died in Hendersonville on October 29, 1996, of cancer.

Sportswriter Joe Falls described Blackwell as “for one season—1947—the most intimidating pitcher of all time.”20 For years after he retired, every sidearm fireballer was compared to him. Later in life Blackwell didn’t dwell on the illness and injury that stunted his career, but he loved to remember the good times. He recalled a train ride home from Pittsburgh after the last game of one season. The Reds’ party got so rowdy that the conductor threatened to kick them off. When the players ran out of booze, they picked up more at a stop along the way. By the time they reached Cincinnati, most of them had lost their shirtsleeves, some had lost their entire shirts, and several had been relieved of their undershorts. “We were the drunkest, happiest, noisiest baseball team that ever got off a train. But then, all of a sudden, you could have heard a pin drop.” They saw their wives waiting on the platform. “Very quietly we all shook hands, wished each other a good winter, promised to meet again in the spring, and then went home to face the music.”21

Notes

1 Richard Goldstein, “Ewell Blackwell, 74, Pitcher Noted for His Whip-Like Style,” New York Times, October 31, 1996, D21.

2 Red Smith, “Views of Sport,” New York Herald-Tribune, reprinted in The Sporting News, July 2, 1947, 5; Joe Williams, “Cincinnati Story: as Blackie Goes, So Go Pilots of the Reds,” The Sporting News, April 5, 1950, 4.

3 Jimmy Burns, “O’Neill and Rolfe, Pilot Extremes,” Ibid., March 28, 1951, 6.

4 Tom Siler, “Baseball Has Never Seen the Like,” Saturday Evening Post, April 17, 1948, 23.

5 William Fay, “Ewell the Jewel,” Chicago Tribune, September 7, 1947, C7.

6 Siler, “Baseball Has Never Seen the Like,” 162.

7 Smith, “Views of Sport”

8 Fay, “Ewell the Jewel”

9 Ed Rumill, “Blackie Just Missed Rare No-Hit Feat,” Christian Science Monitor, September 11, 1965. In Blackwell’s Hall of Fame library file.

10 Arnold Rampersad, Jackie Robinson: A Biography (New York: Random House, 1997), 183.

11 New York World-Telegram, July 10, 1947. In Blackwell’s Hall of Fame library file.

12 Donald Honig, Baseball Between the Lines, in A Donald Honig Reader (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1975), 273-4.

13 Baltimore Afro-American, May 24, 1947, 17.

14 Goldstein, “Ewell Blackwell, 74;” Bud Greenspan, “Fear: The Normal, Crucial but Ignored Factor,” New York Times, January 18, 1981, 2S.

15 Grantland Rice, “Setting the Pace,” New York World-Telegram, January 24, 1950. In Blackwell’s Hall of Fame library file.

16 Honig, Baseball Between the Lines, 274.

17 Brad Willson, “Veteran Barlick Honored as Umpire of Year,” The Sporting News, February 20, 1971, 30.

18 Honig, Baseball Between the Lines, 275.

19 “Blackwell Quits Baseball; Arm that Won 22 Fails,” New York World-Telegram and Sun, March 6, 1954. In Blackwell’s Hall of Fame library file.

20 Joe Falls, “Purely Prejudiced Choice,” The Sporting News, August 3, 1974, 29.

21 Honig, Baseball Between the Lines, 276.

Full Name

Ewell Blackwell

Born

October 23, 1922 at Fresno, CA (USA)

Died

October 29, 1996 at Hendersonville, NC (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.