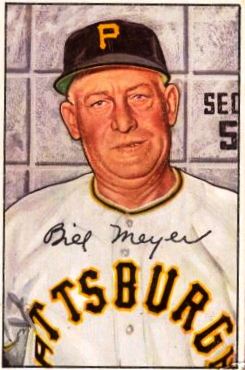

Billy Meyer

The apex of Billy Meyer’s major league career came in 1948, when The Sporting News named the rookie pilot as Manager of the Year. He kept an undermanned Pittsburgh Pirate team in the middle of the pennant race until late September. That accomplishment sealed his reputation as a quintessential “baseball man.”

William Adam (“Billy” or “Bill”) Meyer was born in Knoxville, Tennessee, on January 14, 1892. He began his baseball career with a Knoxville town team. Bill caught, and an older brother pitched. When he was 17, Bill and several of his Knoxville teammates spent the summer playing semipro ball in Lakeland, Florida. His father, a brewer, had reluctantly given permission for the trip, and expected the boy to call home for help. To his father’s surprise, Bill lasted the whole summer, arriving home with a little money in his pocket. After one more year of school, Meyer began his professional career with the hometown Knoxville Reds in 1910.

After three seasons in Knoxville, and one in Winona, Minnesota, Meyer joined the Chicago White Sox for a late-season look in 1913. The 5′ 9″, 170-pounder, who batted and threw right-handed, made his debut on September 6 and collected a single in his first and only at-bat, before he and his 1.000 average were shipped back to the minors. He split 1914 between Winona and Lincoln, Nebraska. After a year in Davenport, Iowa, Meyer joined the Philadelphia Athletics in 1916.

The 1916 Athletics were one of the worst clubs in major league history, finishing 36-117, 541/2 games out of first, and 40 games out of seventh. Meyer was one of several catchers with the club. Wally Schang, the once-and-future regular, injured his hand on opening day, and would spend much of the season in the outfield. This opened a spot for Meyer, the 24-year-old rookie, and he caught more games than any of his teammates. Meyer would later recall that this was due to Connie Mack’s penchant for putting a valuable player like Schang safely in the outfield when young, unproven, pitchers were on the mound, leaving a more expendable player like Meyer behind the plate to deal with the day’s wild pitches. The woeful performance of the 1916 A’s pitchers gave the rookie catcher plenty of experience.

After a second season with Philadelphia in 1917, this time as a full-time backup to a recovered Schang, Meyer would never see the majors again as a player. In his major league career, Meyer batted 301 times in 113 games, garnering 71 hits for a .236 average and scoring 15 runs. He had seven doubles, three triples, a lone home run, and drove in 21 runs.

Back in the minors with Louisville of the American Association, Meyer roomed with the Colonels’ second baseman, Joe McCarthy, and began an association with the future Hall of Fame Yankee manager that would last nearly 30 years.

McCarthy became Louisville’s player-manager in mid-1919, and stayed with the club through 1925. Meyer caught through the entire span. The Sporting News recognized Meyer as the rare veteran catcher who still had relatively uninjured hands. Meyer claimed that, to that point at least, he had never broken a bone in either hand. He attributed this to good luck, as well his habit of keeping his throwing hand out of the way of pitched balls until the last instant. Meyer did break a leg in 1925, but his hands remained relatively healthy.

McCarthy left Louisville in 1926 to manage the Cubs, and Meyer took over at the Colonels’ helm. After the team won the American Association pennant in his first year in charge, Louisville went into a decline, and in 1928 Meyer hinted that he might be moving on, saying that considering the available talent, “someone” would have a hard time winning at Louisville in 1929. The Sporting News sympathized, writing, “Meyer has had a tough time trying to [win] with a half-dozen players and a crowd of sandlotters [and] has-beens.”

The rumor mill had him going to Chicago to become McCarthy’s pitching coach, but instead Meyer began a three-year stint in Minneapolis, as an assistant to the Millers’ long-time owner and manager, Mike Kelley. Meyer referred to this job as “the best experience that I ever had. Mike Kelley gave me more tips about baseball than I ever knew before.”

While Meyer was at Minneapolis, Joe McCarthy had switched leagues, taking over as the Yankees’ skipper. Following the 1931 season, the Yankees began to construct a farm system. They bought the International League’s Newark franchise, as well as Springfield in the then-Eastern League. With Albany, Springfield gave the Yankees two affiliates in that circuit. The Yankees needed a manager for Springfield, and the call went out to McCarthy’s old Louisville roomie. Ostensibly hired as a player-manager, the 40-year-old Meyer began a long managerial stint in the Yankee system.

Meyer had his Springfield club in first place in July of 1932, when Brooklyn and the Giants withdrew financial backing from the Eastern League’s Hartford and Bridgeport clubs and turned the franchises back to the league. With the loss of those clubs and the rest of the league struggling at the gate, the Eastern League as theretofore known suspended operations. Soon a number of new faces began to appear in the box scores for the Binghamton Triplets, the Yankees’ New York-Penn (NY-P) League entry. Nine former Springfield Rifles, along with Meyer and the business manager, had joined Binghamton, spurring the Triplets to move up to a fifth-place finish. By 1938, the NY-P League, having survived the worst of the Depression, added teams in Hartford and Trenton and became the “new” Eastern League.

With future big leaguers Willard Hershberger (Cincinnati) and George McQuinn (Cincinnati, St. Louis Browns, Philadelphia A’s, New York Yankees) joining him in Binghamton, Meyer won the 1933 NY-P League pennant. The addition of Spud Chandler, a future Yankee All-Star, helped the Triplets to yet another in 1934. The Yankees promoted Meyer to manage their Oakland club in the Pacific Coast League at the end of the 1935 Binghamton season.

After the 1936 and 1937 seasons in Oakland, the Yankees moved Meyer to their newly acquired Kansas City club in the American Association for 1938. There, with the help of infielders Phil Rizzuto and Gerry Priddy, he won two pennants and one Little World Series in four seasons and was named 1939 Minor League Manager of the Year by The Sporting News.

Meyer received his first serious consideration for a major league managing job in 1940, according to a 1951 reminiscence. As Meyer recalled it, his friend Bill Essick was in line for the Cubs’ general manager job, and Meyer thought that he might be named as the new Cub manager. But when Jim Gallagher became the general manger instead, he hired Jimmie Wilson to manage. A year later, Meyer was recommended as the replacement for Cleveland’s ousted Ossie Vitt. The Indians ultimately decided against hiring another Yankee minor league manager, and signed Roger Peckinpaugh in 1941 instead. Meyer remained in Kansas City for another season.

From Kansas City, Meyer moved within the Yankee system to Newark of the International League, where in four seasons his teams never finished lower than second place. This wasn’t enough for some fans, however, and a frustrated Meyer told The Sporting News in late 1945: “I’m not returning to Newark. I’m washed up in that town. I’ve been booed out.” He still hoped to land a major league job, but returned to Kansas City again to manage the Blues.

In June 1946, he collapsed during a game with reported “heat prostration.” He rejoined the Blues after missing a few games, but was soon hospitalized with what The Sporting News called a “recurrence of an old heart condition.” Although it was described as “not serious,” he was under medical orders to rest for several weeks.

With Meyer unavailable, Burleigh Grimes filled in as acting Kansas City manager and remained in uniform when Meyer returned. Meyer managed to be ejected from a game when, in street clothes, he joined Grimes on the field to argue an umpire’s call. One wag suggested that the dual-manager system would work well for this Blues team; one could manage the team, the other could spend time in the hospital recovering from the experience, with the two trading off as needed.

By the end of the 1946 season, however, Meyer’s health was still in question. Meyer was on the short list for a number of major league managing vacancies, and said later that he was offered the Yankee job but turned it down. “I had had a mild heart attack in Kansas City,” Meyer later recounted. “I missed a month of the season because of illness. So I felt I wasn’t up to it; fact is, I didn’t even intend to manage in the minors in 1947. My idea was to sit out the season and see how I felt.” The Yankees tabbed Bucky Harris and the Kansas City writers predicted a sixth-place finish for the 1947 Blues. Meyer’s health, however, improved enough to allow him to return to the Blues. In the Kansas City Star, Ernie Mehl reported that the locals rethought their predictions, and now called for the Blues to finish third. Under Meyer, the team outdid that and won yet another American Association pennant.

Meyer managed in the minor leagues for 22 seasons, including his three years as assistant at Minneapolis. His teams posted nine first-place and four second-place finishes. Did he benefit from the talent funneled to him by his clubs? Or did his players flourish because of Meyer’s development skills? Either way, Meyer was a successful manager for a long time, his teams usually did well, and he earned a reputation as a “baseball man.”

Meyer’s route from Kansas City to his major league managing debut in Pittsburgh began in August of 1946, when the Pirates were sold to an ownership group of Frank McKinney, Tom Johnson, John Galbreath and Bing Crosby. The new owners acquired a Pirate club in the seventh year of the mostly-lackluster Frank Frisch managerial era. Other than a distant second-place finish in 1944, the Bucs had not had a whiff of a pennant under Frisch since he came aboard in 1940, and the new owners were looking for a change. Frisch accommodated them by resigning on the 1946 season’s final weekend, and the search for a new manager began. Among the candidates were Kansas City’s Meyer, as well as the Pirates’ own 38-year-old catcher, Al Lopez, the local favorite. Lopez didn’t have enough experience for the job in the eyes of those making the decisions. Meyer’s health made him a questionable choice. Bypassing Lopez and Meyer, the Pirates acquired Billy Herman from the Boston Braves and signed him to a two-year contract as a player-manager. Lopez was offered the manager’s job at Indianapolis, the Bucs’ top farm club. He declined, and spent 1947 in Cleveland as a player-coach.

As the new 1947 Pittsburgh player-manager, Herman didn’t impress. An arm injury suffered in spring training limited him to just 15 games. Further, in exchange for Herman’s services, the Pirates had traded one of their best young players, future National League MVP Bob Elliott. New Pirate Hank Greenberg contributed 25 home runs in his final season, but the rest of the team was about the same as the lackluster 1946 edition and the Pirates finished seventh again. Herman followed Frisch’s precedent when he, too, resigned in the season’s final week. The Pirates again had a managerial opening.

The Pittsburgh papers speculated on the new hire. One possibility was McCarthy, who had been out of baseball in 1947, but he took himself out of the running by joining the Red Sox. Al Lopez still didn’t have major league managing experience, but was offered the job with the Pirates’ top farm club at Indianapolis in the American Association and this time accepted. The Pirates had made a few deals with Pacific Coast League teams, and some saw this as indicating that Lefty O’Doul would leave San Francisco for the Pirate job. Pie Traynor, who had preceded Frisch, was still popular and still in Pittsburgh. Leo Durocher, having served a one-year gambling suspension in 1947, was reported in some circles as actually having accepted the Pirate job, but co-owner Frank McKinney loudly denied any chance of The Lip’s managing in Pittsburgh. From Hollywood, co-owner Bing Crosby said that Durocher would be fine with him, but deferred to his more-involved partners. Durocher returned to Brooklyn.

During the 1947 World Series the Pirates, after first obtaining permission to negotiate with Meyer from the Yankees through Larry Mac Phail, their general manager, made the call that Billy Meyer had been waiting for, and he was signed to a two-year deal noted to be “at the highest salary ever paid to a Pirate field boss.” “I waited a long time, ” he told the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, “but I know I made the right move. This Pittsburgh outfit has the real romance of baseball to it.”

He told local sportswriter Al Abrams that he “was getting frustrated in the minors. Sure, I was winning pennants and developing players, but I wasn’t getting anywhere myself. I had to make this break now or never.”

From the start, the 56-year-old Meyer was well regarded by the Pittsburgh writers. Phrases like “developer of young players,” “a solid man at the helm,” and “should have had this opportunity years ago” regularly appeared in association with him. General manager Roy Hamey said that Meyer was “solid. He plays smart baseball and has both the respect of his players and the opposition.” These high opinions of Meyer’s abilities would not fade. Some of these comments contrasted Meyer, the “manager,” with Herman, who had been “one of the boys.”

The 1948 Pirates appeared to be only slightly improved over the 1947 edition. The club had a legitimate superstar in Ralph Kiner, but not much more than that. After the experiences with Herman and Greenberg, as one-year Pirates, the team began operating on the principle that that homegrown players would serve them better than any veterans they might acquire. The consensus among the baseball writers was that the Pirates were headed for another second-division finish, most likely sixth place.

The 1948 Pirates surprised everyone by spending most of the season in the first division, occasionally approaching first place. There were a number of explanations: Ralph Kiner led the league in homers again, Danny Murtaugh and Stan Rojek both hit .290 and gave the team a better middle infield than they had had in recent years, and the pitching staff, led by reclamation project Elmer Riddle and quadrogenarians Rip Sewell and Fritz Ostermueller, pitched well before fading in September. The team got hot in August and found themselves just three games out of first heading into September.

In the late summer, Pittsburgh fans and writers began to wonder why no prospects from their league-leading farm club in Indianapolis were being promoted to help in the stretch drive. It was speculated that co-owner McKinney, a resident of Indianapolis as well as owner of the club there, was more interested in ensuring that his hometown team did well. Meyer took the heat, claiming that no one at Indianapolis interested him.

On September 17, in second place, four games behind the Braves, the Pirates visited Boston for two games against the leaders. That was, it turned out, as close as the Bucs would get. It would also be the high-water mark of Meyer’s Pittsburgh career. The Pirates lost both games, as well as their next four games at Philadelphia. They quickly slid to a fourth place finish, 8 1/2 games back. Nonetheless, Pittsburgh fans were excited about their Pirates, who won 21 more games than they had in 1947.

The most credit was reserved for Meyer, whose reputation as a “good baseball man” was cemented with that first season. He was The Sporting News Manager of the Year. He was “a sage, understanding old geezer who has a talent for making men do their best for him.” He was regularly referred to as “the best manager in baseball,” at least locally. For the rest of his days in Pittsburgh, Meyer would remain in the writers’ good graces, while the players were seen as responsible for the team’s increasingly poor play.

One local writer, for example, applauded Meyer when he complained about pitchers running in the outfield during a spring training game. It’s a common sight today, but in the 1940s, Meyer thought the fans deserved better. They paid for their tickets, he reasoned, so even spring training games ought to be taken seriously. Meyer also insisted that his players sign autographs whenever possible.

For 1949, Meyer figured that his middle infield of Murtaugh and Rojek was set, and that his outfield of Kiner, Wally Westlake, and a Dixie Walker/Ted Beard platoon combination would suffice. General manager Roy Hamey went further, announcing that with another frontline pitcher and a stronger bat at first base, the Bucs could win the pennant.

It didn’t work out that way, as the Pirates crashed. Kiner threatened Hack Wilson’s National League record with 54 homers, but Beard was not ready for the majors, and the Bucs needed more than a singles-hitting Walker in right. In June, the Pirates signed an Italian-American center fielder from San Francisco, and briefly, Dino Restelli looked like the second coming of Joe DiMaggio. But after three blazing weeks, Restelli stopped hitting, and would never shine as brightly again. Rojek’s average dropped to .244, and Murtaugh’s offensive collapse relegated him to the bench in favor of Monty Basgall. Hamey did get that new starter, Murry Dickson, but the former trio of Riddle, Sewell and Ostermueller, winners of 32 games in 1948, declined sharply. Sewell won six times, Riddle just once, and Ostermueller had retired. The 1949 team won 12 fewer games than the 1948 club and finished sixth, 26 games out.

Meyer’s health problems lingered, as well. During an August series in St. Louis, Meyer came down with what was called “acute indigestion” while talking with reporters in his hotel room. He felt better after a visit to the hospital, but the team doctor ordered him back to Pittsburgh for a few days of rest.

The high point for Meyer in that disappointing 1949 season may have come during the opening week, when his image appeared on the cover of the Saturday Evening Post as one of the managers discussing the weather in Norman Rockwell’s famous “Three Umpires.”

As the 1949 season wore on, some fans began to show impatience with Meyer, although the writers, by and large, did not. Fans criticized Meyer’s performance and accused the sportswriters of being overprotective of him. The writers responded that the players were losing games, not the manager. Meyer was under contract for two more years, but it was expected that several players would not be back for 1950.

A housecleaning may have been intended, but most of the regulars were back for 1950, with disastrous results. The team continued to age, and now that some of the hopefuls from Indianapolis were finally reaching the majors, they didn’t impress Meyer. “Some of them,” he told the Post-Gazette, “weren’t good enough to play [Triple-A] ball, so how could I play them up here? I tried to go along with some of them as I could, but this only made matters worse.” Meyer was encouraged by prospects like outfielder Gus Bell and pitchers Vern Law and Bob Friend, but they were the cream of a thin crop. The 1950 team fell to last place, and Meyer’s future was in doubt. A “saddened and bewildered” Meyer said, “I won’t quit, and I’m not quitting now. It’s up to the owners. If they want me back, I’ll be very happy to return.” He almost didn’t have to add, “This year has been a nightmare.”

Back in 1946, the new owners had announced that they intended to bring a winner to Pittsburgh in a few years. Instead, after four seasons of effort, they had what they had started with–the worst team in the National League. When they talked about a housecleaning this time, they meant it. In November, Pirate management, which by now did not include McKinney, who had sold his interest in the club to his partners, hired Branch Rickey as the new Pirate general manager.

In personnel discussions with Rickey, Meyer said that he had tried to get rid of several players, only to be overruled by management. Meyer himself was ending the first year of a two-year contract, and was not sure of his own status. Rickey, however, was not about to fire a manager he’d still have to pay or to issue any new multiyear contracts.

In the spring of 1951, perhaps stung by criticism that he had let the team get away from him, Meyer ran a tougher camp than he had previously. Beer was banned from the clubhouse, and the players now faced a curfew. Meyer also faced some controversy with his star, Ralph Kiner. At Rickey’s suggestion, Meyer moved Kiner to first base. Kiner objected, but ended up spending about a third of the season at first, rather than his accustomed post in left field.

The 1951 team continued the struggles of 1950. Kiner led the league in homers again, and Dickson won twenty games, but it was not nearly enough. The Pirates finished seventh, just two games out of the cellar.

By this time, the club was operating fully under Rickey’s philosophy. No longer trying to create a contender by finding established players where they could, the Bucs, under Rickey, had two main rules: 1) use as many young players as possible, and 2) spend as little money as possible.

Uncertain as to whether he would be back in 1952, Meyer was among the Pirate personnel present when Rickey held a “school,” as he called it, for over 50 Pirate prospects at Deland, Florida, in October, 1951. The core for some clubs that would win in the not-too-distant future, represented by Vern Law and Frank Thomas, was there, but things would get worse for the Pirates before they got better. Meyer ultimately signed a one-year contract for 1952, the standard term for Rickey employees.

Evoking memories of Meyer’s rookie year with the 1916 A’s, the 1952 Pirates he managed are recognized as another of the most inept teams in major league annals. Winners of just 42 games, the 1952 Bucs finished 54 1/2 games out of first place. The losing took its toll on Meyer, now 60. He had had another short hospital stay in 1951 due to ulcers, and he was no longer the calm and patient gent he had been, showing a shorter temper and displaying a sterner outlook.

In 1952, Dick Groat had jumped directly from Duke University to Forbes Field, Gus Bell continued to improve, and Kiner led the league in homers again. Beyond that, the team was bereft. Trying to cut costs, the Pirates regularly played with fewer than the 25 men allowed on major league rosters; by July, they were getting by with just 21. Besides the decision to employ a less than full roster, the players the team did use were often not of major league quality. This was partly the result of agreements with the Pirates’ top minor league affiliates in Hollywood and New Orleans. The Bucs had agreed not to call up players who might be able to play a role in those teams’ pennant races, and were left to choose from players in lower leagues.

In a story recounted after his death, Meyer was said to have told of a Pirate-Cardinal game during this period. One of Rickey’s “bonus babies” had reached base, and Meyer flashed the “steal” sign to his third base coach for relay. On the first pitch, nothing happened. Meyer put the sign on a second time. Again, the runner stayed put. Meyer tried a third time, with the same result. Finally, the Cardinal second baseman called time, walked over to the runner, and told him, “Look, they’ve given you the steal sign three times now. Are you going to stay on first all day?”

With two games left in the 1952 season, Meyer had finally reached his limit. He resigned on September 27 ending his major league managing career, all with the Pirates, at 317-452 (.412). “I’ve had enough,” he said. “I just couldn’t stand being with this team any longer. These kids we have now just can’t do it. If there was a foreseeable future to the club, I wouldn’t mind sticking it out. Everyone likes to manage a winning ball club, but this one is hopeless.”

In December 1952, Fred Haney became the new Pirate manager. For the rest of his career, Meyer served as a scout and “troubleshooter,” a title he enjoyed. “That would make me the busiest man in the world,” he said. “Lord knows we’ve got enough trouble to shoot at on this club.” He attended spring training with the Pirates through 1955, but worked mostly out of his home in Knoxville.

While giving Rickey a report on the phone in May of 1955, Meyer suffered a stroke. He survived, recovering somewhat from partial paralysis, but his health never fully returned and his baseball career was over. Meyer was suffering from uremic poisoning when a heart attack ended his life on March 31, 1957, in Knoxville. He was survived by his wife, the former Madelon Walters. The couple had no children.

Pittsburgh writers remembered him fondly. Les Biederman, in the Press, called Meyer “one of the best liked men ever to come into baseball. He was popular with everybody: players, managers, coaches, owners, umpires, writers and the fans.” Chet Smith said that a “more charming, witty, philosophical and patient man has never been in baseball. Nor a better manager . . ..” The Post-Gazette‘s Jack Hernon remembered his days as a rookie beat writer. Meyer, Hernon recalled, insisted that his players go out of their way to co-operate with Hernon. “He never carried a dislike for anyone; never did he speak a harsh word about a friend or associate.”

A month after Meyer’s death, the city of Knoxville renamed the town’s ballpark “Bill Meyer Stadium.”

At some point, the Pirates retired Meyer’s uniform number (No. 1), and it shares a place of honor with the retired numbers of more familiar Pirates like Wagner, Traynor, and Clemente on an upper deck façade in Pittsburgh’s new PNC Park. There is no record of a “Bill Meyer Day” or any other ceremony at which his number might have been retired. No Pirate media guide of the period mentions newly-retired numbers, but since the final weekend of the 1952 season, no other Pirate has worn Billy Meyer’s No. 1.

Sources

O’Toole, Andrew, Branch Rickey in Pittsburgh (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Co.) 2000

“Bill Meyer Named Pirates’ Manager” New York Times, October 3, 1947, p. 33

www.baseball-reference.com

The primary sources for information of Meyer’s minor league career were contemporary reports in The Sporting News and the annual Baseball Reports. His time with the Pirates was reported in the Pittsburgh Press, the Pittsburgh Sun-Telegraph, and the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. Meyer’s “reminiscences” refer to three ghostwritten autobiographical articles in the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette following his hiring in Pittsburgh. The author also consulted April 1957 obituaries from The Sporting News, the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, and the Pittsburgh Press.

Photo Credit

The Topps Company

Full Name

William Adam Meyer

Born

January 14, 1893 at Knoxville, TN (USA)

Died

March 31, 1957 at Knoxville, TN (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.